The latter allowed the panzerschreck to use the rocket projectiles already developed for another newly adopted weapon, the Raketenwerfer 43 Püppchen. The warheads of these rockets were later used for the Panzerfaust 150.

The latter allowed the panzerschreck to use the rocket projectiles already developed for another newly adopted weapon, the Raketenwerfer 43 Püppchen. The warheads of these rockets were later used for the Panzerfaust 150.

Added 7-6-2021

Updated 4-5-24

In 1942, the nature of infantry weapons changed.

On one side of the Atlantic, the 2.36" bazooka, the first man-portable anti-tank rocket launcher, was adopted by the US Army.

In Britain, the first PIATs entered production in November.

Over in Europe, the German army was adopting the faustpatrone.

The faustpatrone was not a rocket launcher, but a very simple recoilless gun that threw a large-calibre bomb. Like the bazooka, it used projectiles with hollow-charge warheads. Unlike the bazooka, the faustpatrone was a one-shot, one-use weapon. Once fired, the launch tube could be discarded.

With a number of product improvements, the faustpatrone would become the panzerfaust family of weapons.

When the first bazookas were captured in Africa and Russia, the Germans wasted little time in building their own version, adding a number of improvements such as increasing the calibre. The latter allowed the panzerschreck to use the rocket projectiles already developed for another newly adopted weapon, the Raketenwerfer 43 Püppchen. The warheads of these rockets were later used for the Panzerfaust 150.

The latter allowed the panzerschreck to use the rocket projectiles already developed for another newly adopted weapon, the Raketenwerfer 43 Püppchen. The warheads of these rockets were later used for the Panzerfaust 150.

Neither rockets nor recoilless guns were by any means new. What was new was that these weapons were in a form that could be operated by a single infantryman.

In the past, if an infantryman wanted to cause major destruction, he would have to throw a grenade or utilize hand-emplaced devices such as satchel charges. Grenades had only a small explosive content. Using satchel charges and similar was a high-risk endeavour.

With a bazooka or panzerfaust, the infantryman could remain at a relatively safer distance. A single man now had the hitting power of a field piece. These shoulder-launched munitions (SLM) were the first man-portable anti-tank systems (MANPATS). Unremarked by most, the Bazooka Age had begun.

Weapons such as the bazooka or panzerfaust could be carried across terrain that it was impossible to move an anti-tank gun across. Not only did the infantry now have a potent defence against enemy tanks, they had the means to act more aggressively. Man-portable weapons allowed the infantry to utilize available cover to stalk tanks and attack the more vulnerable side and rear areas. Even the King Tiger tank was vulnerable to the bazooka if the hull and turret side armour was targeted. The panzerfaust had a shorter range than the bazooka, but more powerful warhead.

It was not long before the infantry realized their bazookas or panzerfausts could be used on targets other than tanks. Bunkers, machine gun nests, sniper positions and various obstacles could be destroyed by bazooka or panzerfaust. Weapons intended to destroy tanks proved even more effective against lightly armoured and unarmoured vehicles or artillery.

Against large targets such as a vehicle parks, bazookas could be used at 650-700 yards range.

One target that the bazooka did have trouble with was infantry. Most of the shaped-charge blast would go into the ground and very little fragmentation was produced, limiting the effect area. An interesting solution was found by one GI:

“In 1944, during the sticky infantry fighting around the northern France bridgeheads, a certain sergeant hit upon a field expedient for producing a more effective grenade-thrower. He unscrewed the warhead from a Bazooka projectile and in its place fitted on two standard US hand-grenades, in tandem. The attachment must have been very crude, but it worked. The loader pulled out the pins on the grenades as he gingerly inserted them into the breech of the launcher, the firer shot them off, and four seconds later there was a most satisfying explosion accompanied by a shower of shrapnel [sic. fragments]. Picatinny Arsenal was persuaded to make up 90,000 of these projectiles, which it did—under protest—and they were rushed to France. By that time the battle had moved away from the hedgerows and ditches of the Bocage and the need was less urgent.”

Men Against Tanks. John Weeks.

It seems more likely that the two grenades were placed in the breech of the bazooka and a separate rocket motor inserted behind them.

The Picatinny-designed version seems to have been two adaptors. One adaptor allowed two Mk.II fragmentation grenades to be joined base to base. The other adaptor allowed a rocket motor to be attached to a grenade’s fuse well. The other grenade retained its pin and lever. The pin had to be pulled before the rocket was inserted into the bazooka.

Both HC and WP smoke rounds for the bazooka were made, and were used in combat. A round developed containing toxic cyanogen chloride (CK) was not used in combat, nor was a thermite round.

Panzerfaust only saw action with an anti-tank warhead.

Proposed variants included Gasfaust, containing tear-gas, Brandfaust with an incendiary warhead, and Flammfaust containing flammable liquid. Schrappnellfaust was a reloadable panzerfaust-type launcher that threw an anti-personnel warhead 400m. None reached the troops before the war ended.

The Panzerfaust 150 was to have the option of a “splinter-ring” that could be added to the warhead for increased fragmentation effect.

Bazookas were typically held at company or platoon level. Some mechanized units acquired a bazooka for each vehicle. The M20 Utility Car carried a bazooka as part of its standard armament.

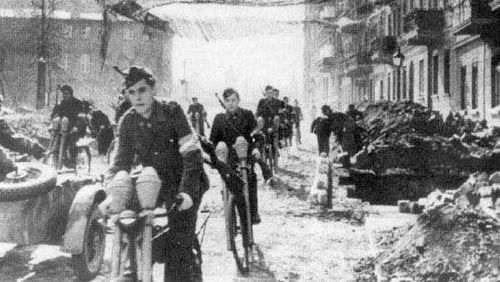

The panzerfaust was treated as a round of ammunition, much like a hand-grenade. Officially, rifle and combat engineer companies were to have 36, other companies 18 and artillery batteries 12. In practice, front-line units acquired greater numbers. Numerous photos exist of bicycle-mounted troops or Hitler Youth, each carrying a pair of panzerfaust.

At least 6.7 million panzerfaust are estimated to have been produced, each costing only 15-25 Reichsmarks.

While the bazooka and panzerfaust revolutionized personal firepower, recoilless weapons made inroads in another area. Both Germany and America issued recoilless weapons intended to serve as infantry and/or anti-tank guns. As shortcomings in propellant manufacture began to be felt, the German weapons saw relatively little use. America had no such worries.

The first weapon produced was the 57mm M18 recoilless rifle (RCLR), soon followed by the 75mm M20.

The M18 massed 45 lbs/20 kg in shoulder and bipod-firing configuration, more if mounted on the 15 kg M74 or 24 kg M1917A2 tripod.

The M20 was 114 lb/52 kg, but could not be fired without a M74 or M1917A2 tripod, which took the mass up to around 147 lb/67 kg.

While too heavy to be considered “man-portable”, either weapon and its ammo could be handled by a relatively small crew, and were no more a burden than other some infantry weapons such as medium machine guns or mortars.

The role of these recoilless rifles was to engage enemy armour at ranges greater than was possible with a bazooka. The performance of these weapons was adequate for this role and they effectively rendered the battalion-level conventional anti-tank guns obsolete.

A US infantry battalion was at this time issued three M1 57mm anti-tank guns, each massing 2,679 lb. These weapons were already ineffective against the frontal armour of the heavier tanks being fielded.

The M18 and M20 also served as the battalion’s “pocket artillery” that could be carried to firing locations a conventional anti-tank gun could not.

During the Korean War, the company-level M18 and battalion-level M20 were the only weapons that could be moved across the hilly terrain to deliver direct fire against bunkers, sometimes at ranges exceeding 1,000 yards. The heavier 75mm was longer-ranged, but the 57mm proved useful in the more mobile, final phases of an assault. (Commentary on Infantry Operations and Weapons Usage in Korea, Winter of 1950-51. SLA Marshall)

This utility of the recoilless rifles was increased by both the M18 and M20 being provided with a variety of ammunition types. Both weapons had their own HEAT, HE, smoke and canister loadings. In contrast, the US version of the 57mm anti-tank gun was mainly issued only armour-piercing shot and HE rounds for it were difficult to come by, limiting its support fire utility.

As the Second World War ended, the usefulness of the US 57mm anti-tank gun against modern tanks was questionable.

Larger calibre anti-tank guns were too heavy to manhandle and required vehicular assistance to move, so the US Infantry had little interest in them.

Larger-calibre recoilless guns were in development, and seemed likely to outperform conventional anti-tank guns while still weighing under 600 lbs.

Despite this, conventional anti-tank guns were slow to disappear. Several nations continued to develop conventional heavy anti-tank guns in 75-100mm calibres.

During the Korean War, the US made available to its allies its stockpile of more than 10,000 57mm guns!

The success of the bazooka and the panzerfaust inspired a number of new designs. The reloadable bazooka would eventually be replaced by a single-shot, disposable rocket launcher, the 66mm M72 LAW. Like the panzerfaust, the M72 could be treated as an expendable round of ammunition. Its light weight (5.5 lb/2.5 kg) and compact size made it a handy weapon to carry even if a tank threat was not anticipated. Conversely, the disposable panzerfaust would inspire one of the better known reloadable post-war anti-tank weapons, the RPG‑2, and from that, the RPG‑7.

The original bazooka rockets were fired electrically. This required the loader to attach an igniter wire from the rocket motor to the launcher. Post-war designs understandably eliminated this fiddly operation.

One solution was to issue the rocket in a container that also served as a shipping and transport container. Rather than remove the rocket and insert it into the breech, the entire container was attached to the rear of the launcher. This configuration has been used on a number of designs, but is probably most familiar as that used on the SMAW/B-300.

While this configuration is common, no specific term for it appears to be in use. The author suggests “launch-container configuration”.

While back-blast is often listed as a problem with SLMs, designs such as the Arnbrust, with the capability to be used from confined spaces, were slow to gain acceptance.

Recoilless guns were to get both bigger, and smaller.

Recoilless guns were to get both bigger, and smaller.

America fielded the very successful M40 106mm weapon, and also the 90mm M67. The latter was intended to fill a bazooka-type role, but massed around 37 lbs/17 kg unloaded.

More commonly encountered than the M67, the Swedish 84mm Carl Gustav recoilless weapon massed 31 lb/14.2 kg in its early forms. Since 1948 the weapon has undergone numerous improvements, the latest version massing only 14.5 lb/6.6 kg while having equal or improved performance.

The Swedish 84mm AT4 (M136) is a single-use recoilless gun. In recognition of realistic infantry tactics, the designers did not attempt to create a weapon that could penetrate modern MBT frontal armour. Like weapons of similar calibre, the AT4 is usefully employed against the sides and rear of a tank.

Many modern single-use launchers are in fact recoilless guns rather than rocket launchers. The term “rocket” is often used wrongly, even in technical publications such as JIW.

The RPG‑7 and some other systems are hybrids, using a recoilless system to launch a rocket-propelled projectile.

While many nations adopted the M40 106mm, a number of other nations produced their own designs of crew-portable recoilless weapon.

Of these, the most significant were probably the Soviet 82mm B-10 and 73mm SPG-9 Kopye. These are unrifled weapons, so are correctly termed “recoilless guns” (RCLG) rather than “recoilless rifles”.

China produced its own copy of the B-10, improving and lightening it as the Type 65, Type 65-1 and Type 78.

China also copied and produced the M18 as the Type 36 and the M20 as the Type 52 and Type 56.

At least as late as 2002 Jane’s Infantry Weapons (JIW) listed the M18 as available from Hydroar of Brazil. Ammunition for the M18 was available from Brazil and Italy.

Supposedly, crew-portable recoilless guns are now obsolete, and have been replaced by guided anti-tank missiles. I will discuss this further a little later.

Most of the post-war man-portable SLMs have been designed with the anti-tank mission as their primary role. Indeed, many are only available with HEAT warheads.

An early exception to this was the M202 FLASH, a four-shot launcher for incendiary rockets. The M202 was created as a longer-ranged alternative to the backpack flamethrower. A CS rocket for the M202 was apparently planned, but never issued.

The original Soviet RPO also used an incendiary rocket. More common is an RPO using a thermobaric round. Some confusion exists since the Russians also call thermobaric rocket launchers “flamethrowers”.

A number of Russian anti-tank systems are also available with thermobaric warheads. These include disposable launchers like the RPG‑26, the RPG‑7 and several ATGW. Thermobaric rounds for the SPG-9 are also available.

After World War Two, the scale of issue of MANPATS increased in many armies. Generally, weapons became organic to the platoon or squad. Lightweight throwaway systems such as the M72 might be carried by several members of a rifle squad.

Despite this, the full potential of the capability this provided does not seem to have been fully appreciated in many conventional forces.

The use of bazookas and panzerfausts in the war had caused some tactical changes. If a machine gun team remained in the same place too long, they became vulnerable. For bunkers and other static positions it was only a matter of time before bazookas, recoilless guns, PIATs or panzerfausts were used against them. Vehicles that moved without an infantry screen could be easily destroyed. Even tank crews became more cautious and vigilant.

After the war, these inconvenient restrictions were forgotten. These lessons would be retaught, and paid for in blood.

Many of the post-war innovations and refinements in using MANPATS have originated from their use by guerillas, insurgents and terrorists. While it is usual to think of the AK-47 as the symbol of revolution, it can be argued that the RPG has achieved more.

Many of the post-war innovations and refinements in using MANPATS have originated from their use by guerillas, insurgents and terrorists. While it is usual to think of the AK-47 as the symbol of revolution, it can be argued that the RPG has achieved more.

Significant for some users is that rocket launchers and similar weapons are easier to manufacture than more traditional infantry weapons.

Many irregular forces make use of multiple launchers. While a conventional infantry squad might have a single anti-armour weapon, a similarly sized guerrilla force might carry several such weapons. High value targets might be engaged by salvoes from multiple weapons.

A refinement of this is the so-called “swarm” tactics employed in conflicts such as Grozny. Multiple anti-armour weapons attack from multiple directions. What a professional soldier might mistake for a highly coordinated attack demanding a high level of communication is in actuality quite the opposite; small, independent teams choosing any target of opportunity.

In some instances, close range attack with multiple MANPATS has been coordinated with longer-ranged attacks from ATGWs. Use of MANPATS force tank crews to button-up, reducing their visibility and situational awareness. Damage from MANPATS against defensive and communication systems makes tanks more vulnerable to ATGW attack.

The supposedly obsolete crew-portable recoilless guns remain popular with various militant groups. Many such groups do not have access to guided anti-tank weapons. Even if this were not so, many lack the technical resources to keep these weapons working. Conventional artillery weapons are too heavy and immobile for guerrilla (or conventional infantry!) operations. Recoilless guns, however, are relatively light, and fire large, destructive shells to useful ranges. They are simple to operate and maintain. As direct-fire weapons they do not require the training nor practice that might be required of an effective mortar crew.

Viewed in this light, it becomes obvious why the 57mm M18/Type 36 has remained popular with certain guerrilla forces.

It is light enough to be moved by a small group of men, and still effective against most targets that are not an MBT. Unlike an RPG, it can engage certain targets at a range of several kilometres.

The Peruvian Shining Path group allegedly used M18s to force their way into bank vaults. (Guerrilla Warfare Weapons. Terry Gander, p.132)

Heavier crew-portable recoilless guns are also used by guerrilla groups. Their greater mass is often dealt with by the simple expedient of carrying or mounting them on pickup trucks and similar vehicles.

Many of the “technicals” seen in the Middle East and elsewhere, are armed in this fashion.

They can provide tank-like firepower from beyond the range of most infantry weapons, mounted on a platform with greater speed (although less protection) than a most military vehicles.

Anti-tank weapons are often used against targets that are not tanks. Many potential future adversaries will not have tanks.

Recognition of this has lead many manufactures to offer at least two types of round for their weapons.

Typically, one round is an anti-armour round. Many modern designs have a tandem warhead intended to counter explosive reactive armour (ERA).

The second variant is usually either thermobaric, or some variety of HE-Frag, HEDP or HEMP. These are anti-personnel/explosive rounds which have some penetrative ability against light armour or buildings.

The capability to create wall breaches (“mouseholes”) big enough for infantry to enter is often desirable.

Bunker defeat munitions (BDM) for use against more fortified structures are another possible option.

Given that weapons such as the M72 were frequently used against non-tank targets, it is surprising how many decades it has taken for anti-personnel or HEDP versions to be adopted!

The mass and bulk of SLMs and their ammunition limits the number of rounds that a unit or individual can carry. This suggests that a small selection of very versatile rounds is a better option than a wide selection of more specialized rounds.

Several decades ago I wrote about some of the possible forms future MANPATS might take.

Guided weapons of man-portable weight have been slow to appear. The Saab MBT-LAW/NLAW uses inertial guidance to keep the missile on a predicted line of sight trajectory(PLOS) intended to intercept a target. The Rafael Spike-SR uses imaging infra-red guidance.

MANPATS using disposable launch containers have become the norm.

China, for example, seems to have replaced its RPG‑7/Type 69 weapons with the PF-89 and DZJ-08 series.

Two interesting exceptions to this trend also come from China.

One is the single-shot Type-70-1 62mm weapon, the other the double-barrelled 62mm FHJ-84.

The Type 70-1 resembles the original bazooka in both appearance, performance and calibre. It is loaded by attaching a launch-container to the rear of the tube.

Although it is described as an anti-tank weapon, it seems likely that the Type 70-1 is intended for non-tank targets. It may have been designed specifically for special forces or guerrilla use.

According to Jane’s Infantry Weapons 2002, the GRP launcher weighs around 2 kg and each HEAT round 1.18 kg.

Clearly, for the small calibre rounds used, a reloadable launcher allows the user to carry more reloads than the equivalent number of similar calibre disposable launchers.

The FHJ-84 might be expected to be an evolution of the Type 70-1, but is apparently used with incendiary and smoke rockets, making it an equivalent of the M202.

The rounds for the FHJ-84 seem to be based on those of the Type 70-1, so it is possible the FHJ-84 can also fire HEAT rounds and vice versa.

An interesting approach to active protective systems is shown by the RPG‑30.

The RPG‑30 is a double-barrelled launcher, with one barrel of smaller calibre than the other. The smaller calibre rocket flies ahead of the larger, and prematurely triggers any active protection systems. This allows the larger calibre rocket to strike home in the delay while the active system resets.

One idea I proposed in my previous article was launch tubes that could be fired with or without a detachable command launch unit (CLU) fitted.

The guided NLAW and Spike-SR both use their integral sights, the Spike-SR using the missile’s own sensors to view the target.

Larger current ATGW cannot be fired without their CLU.

There are designs of non-guided disposable anti-tank systems that can either use their integral sights, or an attached night-sight, so my ULAW prediction has partially come true, and may come true with future guided weapon designs.

For balance, I will note that there are disposable unguided anti-tank weapons that cannot be fired without a separate firing unit attached. The Russian BUR is an example.

Rafael’s Mini-Spike anti-personnel guided missile needs a separate CLU in its current configuration. I would not be surprised if future versions adopt some of the features of the current Spike-SR.

Over the decades, I have seen numerous weapon systems touted as being a replacement for the M72 LAW.

Many of these have never been adopted. A few have been adopted in the anti-tank role.

The M72 is still with us, and the number of forces using it has just grown with time.

Shoulder-launched munitions get used on a variety of targets that are not main battle tanks.

The M72 LAW is a very handy weapon for such targets. It may be carried and used by any rifleman. It does not need any specialized launcher nor aiming system to be carried. The M72 is a compact size to carry and may mass as little as 2.36 kg.

Potentially, an entire platoon could fire rockets at a target simultaneously!

To better reflect its actual use, the British Army has redesignated it the “light anti-structure munition (LASM)”

Although it was being used against a variety of targets, it was a few decades before variants with anti-personnel and other varieties of warhead became available. However, it is not uncommon in military circles for there to be a significant delay in accommodating actual user needs.

A number of other weapons have been created to fill the same niche. The Russian 64mm RPG‑18 differed very little from the American original.

The Swedish 74mm Miniman (2.9 kg) was notable for actually being a one-use recoilless gun rather than a rocket-launcher. Muzzle velocity was a relatively modest 140 m/s.

The French 68mm SARPAC (2.7 to 3.7 kg) used a semi-reusable launcher and was possibly one of the earliest systems to offer alternate HE-antipersonnel and illumination rounds. In a non-anti-tank role, it had a range of 650 to 700 metres.

The French 58mm WASP 58 (3 kg) launched its rocket using a countershot recoilless system that gave the weapon a low firing signature and a confined space launch capability. It is claimed that the weapon can be brought into action within a short interval without lengthy preparation. Projectile velocity was 250 m/s.

Whilst the M72 still dominates the field, there is room for improvement:

A shaped charge with significant fragmentation and incendiary effects is one possibility. A hit to a target such as a truck should also be detrimental to the majority of any passengers or cargo in the rear area.

Such a warhead should have a “smart” fuse which activates immediately when encountering hard surfaces such as armour or brick, but delays detonation when encountering soft obstructions such as sandbags or undergrowth.

The German Armbrust utilized a folding pistol-grip that unfolded to reveal the trigger. Possibly the folding and unfolding of such a grip could also disarm and arm the firing mechanism.

The British LAW-80 incorporated its firing controls into the weapon’s carrying handle. This configuration might be applicable to a smaller, M72 replacement.

Another notable Chinese weapon to appear in recent years is the PF-98, also known as “Queen Bee”. The PF-98 is issued at company and battalion level. It is a 120mm rocket launcher using the launch-container configuration.

In a twist from the usual error, the PF-98 is a rocket launcher often misidentified as a recoilless rifle.

JIW 2002 states the PF-98 has a 6.35 kg HEAT and a 7.55 kg multi-purpose round, with ranges of 800m and 1,800 m respectively. Information on this weapon is still rather patchy, but a mass of 23 kg has been claimed.

It is unclear if this mass is loaded or unloaded, or if it includes the tripod.

Several pictures of soldiers apparently ready to fire or firing from their shoulders exist, suggesting the weapon is lighter.

I have come across puzzled comments about why China should develop such a weapon in a day and age of guided weapons. The answer is for the same reason that China has used and further developed recoilless guns.

The PLA has around 4 million members, but regional troops and militia take the number of possible combatants to four or five times this. Equipping this many troops with ATGWs is not practical, even if China had sufficient resources to keep that many weapons maintained.

Like the recoilless guns it is probably intended to replace, the PF-98 is easily produced, easy to maintain, easy to operate and likely to be combat effective.

Clearly there is a role for a weapon that is intermediate between vehicle-mounted systems and shorter-ranged infantry MANPATS.

I would not be surprised if within the next few decades, the PF-98, something resembling it, or a medium-calibre version, starts appearing on technicals. A round with semi-active laser homing (SALH) may also appear.

There can be little doubt that some future SLM systems will be guided or homing. This will be most likely in those rounds intended to engage moving targets, such as the anti-tank rounds. How common such rounds will be will depend on cost and shelf-life.

Many current guided weapons need a certain level of maintenance and care. One cannot simply leave them in a rack and expect them to work when they are wanted. A force that wished to use such weapons needs a certain level of technical support.

This characteristic also makes it difficult to stockpile large reserves of functional weapons.

It is possible that future models of guided-missile will have lower maintenance demands or incorporate features such as self-diagnostics.

Another consideration is the tactical utility of guided weapons. Many current designs have relatively long minimum ranges.

Part of this is due to the arming distance; the distance at which the warhead-fuse arms.

More significant is the distance that it takes the missile to come under control of its guidance system or capable of course corrections (“gathering distance”).

The Spike-SR, intended for close-range engagements, still has a minimum range of 50 metres. It also takes six seconds to ready for firing, which seems a long time when a tank is within a hundred metres or less!

Many current ATGW systems have even longer minimum ranges. Javelin ATGW needs 65 metres. For comparison, AT4 arms in ten metres, and RPG‑7 in five.

A number of current guided weapon systems use relatively low-velocity missiles. A missile may take twenty to thirty seconds to reach a target at maximum range. This gives a target plenty of time to take defensive measures. Tanks engaged at long range will often only offer their frontal aspects as targets. This is their most armoured aspect and is playing to the tank’s strength rather than exploiting its weaknesses.

Anti-tank gun crews during World War Two would often camouflage their positions and not fire until tanks were within 50 metres. Tanks are long-sighted monsters with tunnel vision. By attacking at close range, gun crews could eliminate several tanks before their firing position could be determined. Armour-piercing rounds were more effective at close range and could be targeted at the side or rear of a vehicle.

Tanks were often allowed to bypass a position so the sides and rear could be targeted.

Recent history has demonstrated that such tactics remain valid. Using ATGWs at shorter ranges reduces a target’s reaction time. Modern infantry with MANPATS or ATGWs have a better chance of escape than a gun crew with a ton of anti-tank gun. This is why some modern forces favour relatively short-ranged, easily manufactured unguided weapons such as RPG‑2 and Yassin.

Interestingly, some armies tend to deploy their ATGW systems like First World War heavy machine guns rather than using the tactics that proved effective for anti-tank guns.

They are positioned for interlocking fields of fire and long lines of sight.

Due to such arrangements, ATGW attacks are directed at a tank’s frontal armour were the tank is best protected.

Engagement is often at maximum visible range. Even when terrain limits this range to under 1,000 metres, there may be ample time to locate and attack the ATGW firing position.

For “tank-stalking” and urban operations there is an obvious need for manportable guided weapons that may supplement weapons such as the RPG‑7, PF-89 and AT4.

Relatively few weapons of this type have appeared so far. Options include the M47 Dragon/Saegheh, Saab NLAW, FGM-172 SRAW Predator and the IMI Shipon. Minimum range for the Predator is 17 metres, and that for the NLAW 20 metres.

Excepting the Dragon and Saegheh, all of the above named weapons use predicted line of sight guidance (PLOS), which eliminates the need for gathering.

These weapons nicely compliment infantry-mobile unguided systems and longer-ranged, heavier weapons such as FGM-148 Javelin or Spike MR, and vehicle-mounted systems.

Some form of homing or terminal guidance to counter evasive manoeuvres by the target would be an obvious improvement.

An approach worth investigating is a wire‑guided SACLOS missile based on a one‑use launch tube of about the size of an AT4. The AT4 is a recoilless gun. A SACLOS system would need a projectile with rocket propulsion. Possibly the warhead of the AT4 could be used, or components of other existing designs

An intended range of less than 1000 metres and shorter time of flight removes many of the objections to wire‑guidance, while rendering the system resistant to most electronic countermeasures.

Unlike a PLOS system, the operator may compensate for changes in target direction or velocity.

If fired from within gathering range, the missile would behave as an unguided ballistic weapon.

To keep mass within reasonable limits, this weapon would be designed for non‑frontal attack.

Unless problems such as minimum range, shelf-life and cost can be solved, unguided SLMs will remain an important component of the infantryman’s arsenal and should not be neglected.

Some thought needs to be given to the size of future SLMs.

For an anti-tank munition with a hollow-charge warhead, a large diameter is desirable, the limit being keeping the weapon man-portable (14 kg/31 lbs).

The RPG‑32 launches 105mm HEAT warheads or 72mm thermobaric rounds. It achieves this by the firing unit accepting a launch-container that can hold either round. The firing unit appears to be simply a mount for the sights and firing mechanism, so is indifferent to the projectile’s calibre. The thermobaric round does not need to be large calibre, and its smaller frontal area and lighter weight doubtless help ballistic performance.

For HEDP/HEMP munitions, it may be prudent to have two sizes of SLM. A round capable of producing usefully sized wall-breaches and attacking light armoured vehicles may need to be at least 80mm. A bunker-defeat munition (BDM) will also need a sizeable warhead.

Large calibre weapons would be complimented by a smaller, lighter weapon, similar to the M72, but designed so it can be brought into action more readily.

This latter weapon may be issued in both lightweight and confined-space launch variants.

A large-capacity smoke munition in a disposable launcher might be useful for some operations, such as peacekeeping or reconnaissance.

An incendiary munition might be useful for the destruction of stores and materials. The need for such a variant would depend on that actual incendiary effects of thermobaric munitions.

The above system may possibly be supplemented by some form of smaller, soft-launch, anti-personnel missiles.

One obstacle to making more use of SLMs is their size and bulk. 2.36" bazooka rounds massed only 3.5 lb/1.6 kg, but were each 19 inches (48.3 cm) long. A two-man RPG‑7 team usually can carry only five to six rounds between them. A Javelin ATGW masses 49 lb/22 kg!

SLMs that do not require a separate launcher are a partial answer. Rather than two men carrying five or six rounds, most members of a squad can carry one or two. Not only does this double or triple the number of rounds carried, but it facilitates tactics such as multiple, simultaneous attacks.

In previous decades, infantry squads were provided with handcarts for moving equipment and ammunition. Similar systems could be easily fabricated. Something like a golf trolley could be used to move a Javelin or several smaller SLMs. No wider than a man, such a trolley can be taken most places a soldier can go. Several soldiers could lift a trolley over many obstacles.

In some of my older articles I suggest a M113 variant I called the Anti-Armour Team Carrier. The interior of the vehicle contained racks for ATGWs and thermobaric SLMs. These weapons were to be handed out to an anti-armour section or other infantry for dismounted use. I also suggested the vehicle mount a 106mm RCLR to give it an additional fire-support role. A gunshield was provided for the 106mm and the machine gun position had an enclosed turret to protect the machine gunner when the 106 was fired. Such a vehicle could also carry a handcart, already loaded with SLMs.

When researching this article, I came across the observation that Second World War US Army dogma was that the best weapon against a tank was another tank. This was suggested as the reason that the US soldier was relatively poorly supplied with adequate alternatives, such as anti-tank guns. The “tank against tank” dogma can be seen to have persisted for at least a couple of the decades after the war.

What if it had not? What if the US Army had fully grasped the potential and effects of the Bazooka Age weapons? What if the army had paid more attention to the concepts proposed by Project Vista?:

The early sixties, somewhere in West Germany. A US Army infantry company advances.

In the lead are a dozen of the new M113 carriers. Each vehicle mounts a .50 calibre machine gun and a 106mm recoilless rifle. Most vehicles mount additional M1919 or the new M60 machine guns as wing guns. These are manned to answer flank or rear attacks from enemy RPG teams. The M113s have additional armour in the form of sheets of expanded metal mesh (XPM). This defence against hollow charge warheads was inspired by the wartime bedframes by the Russians, but the idea was first tried by the Germans. Sloped wire mesh reaches a few feet above the roof of the carrier as some defence against grenades thrown at the open roof hatch.

If we peek inside a carrier we find most of the squad seated. The machine gunners man their weapons, vigilant for threats. The open roof hatch provides welcome ventilation. This is seldom closed unless under nuclear, chemical or artillery attack. Each squad has a 3.5" Super Bazooka. Most riflemen also have a John Henry assault launcher. This is an improved copy of the German Panzerfaust 150 weapon. The lightweight launch tube is cheap enough to be discarded once fired, but can be reloaded if retained. A number of reloads are carried by the M113. Some riflemen carry reloads with them. Additional ammunition is carried in the M59 section that moves with the M113s. This particular M113 vehicle also carries the platoon M202, with a selection of incendiary, high-explosive and anti-armour ammunition.

The company is supported by three “infantry gunfighter” vehicles. After the T165 Ontos was rejected by the US Army, an alternative system was created by mounting four 106mm RCLR on an lowered M113 chassis. This formidable armament is supplemented by a 20mm M139 cannon. Like several of the APCs, the gunfighters are fitted with dozer blades. These act as an additional layer of spaced armour, but can also be used to quickly throw up earthworks to defend vehicles and infantry.Another M113 is modified to launch SS-11 guided missiles. The fifth vehicle in the platoon mounts a single recoilless gun, but this is the 155mm M29A2, a non-nuclear spin-off from the Davy Crockett program. Its HEP (HESH) and HEAT rounds can destroy any tank in the Soviet arsenal.

As an added precaution against enemy anti-tank teams, the column moves with a pair of up-armoured M113s, each mounting a formidable quad .50 calibre mounting.

The infantry company can bring considerable explosive firepower to bear against an enemy, even when dismounted. On the nuclear battlefield there is much to be said for eliminating an enemy quickly. Units that stay in a location too long become easy targets.

By the Author of the Scrapboard : | |

|---|---|

| Attack, Avoid, Survive: Essential Principles of Self Defence Available in Handy A5 and US Trade Formats. |

| |

| Crash Combat Fourth Edition Epub edition Fourth Edition. |

| |

| |