Part One Part Two Part Three Part Five

Part One (longer version)

Now that I've fired Aquinas' fifteen "smoking guns" to the satisfaction of curious readers, and shown that Thomism and Darwinism are fundamentally incompatible, I'd like to put forward a critique Professor Tkacz's paper, "Thomas Aquinas vs. The Intelligent Designers: What is God's Finger Doing in My Pre-Biotic Soup?" in this post. I shall aim my criticisms at both his original talk to the Gonzaga Socratic Club, and the revised version of his talk, published in the journal This Rock.

Let me be clear about one thing up-front. Although I will be accusing Professor Tkacz of mis-representing Intelligent Design on no less than four points in this post, I am not in any way imputing his actions to malice on his part. It may simply be that Professor Tkacz's personal philosophical and theological biases have clouded his judgement, making it difficult for him to discuss ID in an impartial manner. That is perfectly understandable; we all have our own biases. What we need to do is recognize them and overcome them.

This post (Part Four of my reply to Professor Tkacz) will be divided into three sections:

1. GENERAL COMMENTS ON PROFESSOR TKACZ'S PAPER.

2. TKACZ'S FOUR MAJOR MIS-REPRESENTATIONS

My next and final post (Part Five of my reply to Professor Tkacz) will feature a discussion of the Mind of God. I shall attempt to show that Intelligent Design theory is required in order to explain what it means to say that God is intelligent, and how we can know that God is intelligent.

Without more ado, I'd like to address Professor Tkacz's paper.

1. GENERAL COMMENTS ON PROFESSOR TKACZ'S PAPER

Where's the Soup?

The Miller-Urey experiment, which was conducted in 1952 and published in 1953, has often been invoked in support of the "primordial soup" theory. While the experiment readily generated amino acids, recent research (see below) has completely discredited the primordial soup hypothesis for the origin of life.

Professor Tkacz gets off to a bad start with his cheeky title: "Thomas Aquinas vs. The Intelligent Designers: What is God's Finger Doing in My Pre-Biotic Soup?" One gets the distinct impression that if the "finger of God" were ever found in the Earth's pre-biotic soup, Professor Tkacz would be highly annoyed. Unfortunately for Professor Tkacz, his title is already out-of-date, thanks to recent scientific research. The primordial soup hypothesis for the origin of life has been completely discredited, as this report from "Science Daily" (February 3, 2010) shows. According to William Martin, senior author of a recent pioneering paper entitled "How did LUCA make a living? Chemiosmosis in the Origin of Life," in Bioessays (Volume 32, issue 4, pp. 271-280), "soup has no capacity for producing the energy vital for life." The authors of the paper (Nick Lane, John F. Allen and William Martin) make a very strong case that alkaline vents were the primordial source of energy for early life, but modestly refrain from attempting "to plot out exactly what happened at the origin of life." Fair enough, and I look forward to hearing more from them.

Tkacz's Theological Truisms

If Professor Tkacz's science is questionable, his theology is trite. His talk is peppered with theological utterances which convey an impression of profundity, but which are in fact obvious to almost everyone over the age of ten who has been brought up in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Thus we are told that "There is no before for God," that "God creates without taking any time to create," that "Creation is not a change," that "the Creator does not create something out of nothing in the sense of taking some nothing and making something out of it," and that "Creation... is the radical causing of the whole existence of whatever exists." Thank you, Professor, but I think we all knew that. Most of us in the "Intelligent Design" camp heard these things many times when we were children. This is common ground between us; so why make an issue of it?

God of the Gaps?

Throughout his paper, Professor Tkacz naively equates Intelligent Design with the notion that God periodically "intervenes in nature" to create complex biological structures, which cannot be produced by natural processes. He's wrong here; as I and many other contributors to Uncommon Descent have repeatedly pointed out, ID is the notion that certain patterns in Nature (including certain biological structures) possess a property (e.g. specified complexity) which makes it overwhelmingly probable that they were designed by an Intelligent Agent. (There is also a "stronger" version of ID, which asserts the probability of a non-intelligent origin for these complex patterns is precisely zero. I'll say more about this version of ID in Part Five of my reply to Professor Tkacz.) And if Professor Tkacz would like an "official" citation from a leading Intelligent Design researcher, then I would be happy to oblige: according to Professor William Dembski's definition cited at Uncommon Descent, "Intelligent Design is ... a scientific investigation into how patterns exhibited by finite arrangements of matter can signify intelligence." When, where, and how these patterns were designed are of secondary importance to the Intelligent Design project. The production of these patterns could be a supernatural act, or it could be the natural outcome of events that the Creator personally initiated at the Big Bang, when the universe was created. For example, God might have fine-tuned the initial conditions in such a way that life's subsequent evolution was inevitable. Indeed, leading ID proponent Professor Michael Behe even described such a scenario in his book, The Edge of Evolution, published by Free Press in 2007. Now, while Professor Tkacz could be pardoned for not having heard of this proposal when he gave his talk to the Gonzaga Socratic Club a few years ago, he can hardly be excused for repeating his error when he published a revised version of the same talk in the journal This Rock in 2008, after the publication of Behe's book, "The Edge of Evolution."

But I'm not going to harp on this error of Tkacz's in today's post. Why not? Because if I were a betting man, I'd be prepared to bet that the hypothetical front-loading scenario proposed by Professor Michael Behe in The Edge of Evolution, was probably not the way in which complex biological structures actually originated. There was a time when I would have described myself as a "front-loader." But I now believe that God, Who is outside time, continually "adjusts" Nature at every point in time (from our perspective), and that Nature is made to be manipulated: it's an inherently incomplete, open system. In other words, the "gaps" are an all-pervasive, defining feature of Nature. In today's post, I'm going to defend this version of Intelligent Design. And if someone wants to describe this version as "God-of-the-gaps" ID, as Professor Tkacz does, that's fine by me. It's a put-down, but so was the term "Big Bang," when the astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle first coined it, so I don't mind.

The importance of being precise

When articulating his own views, Professor Tkacz exhibits a disturbing lack of rigor and precision - so much so that on some topics, I had to read and re-read his article many times before I could be sure of what he was trying to say. One thing I noticed when I read his paper was that he holds a minimalist view of Divine agency known as "mere conservationism," which would rule out all but one version of Intelligent Design (the "front-loading" version discussed by Behe in his book, The Edge of Evolution), on purely theological grounds. But during his talk, Professor Tkacz also uttered statements which appeared, on a cursory reading, to contradict this minimalist view. It was only by carefully examining the logic of Professor Tkacz's argument against Intelligent Design - which only works if he actually holds the minimalist view I ascribe to him - that I was able to confirm that the initial impression I had formed of his opinions was indeed correct. Had Professor Tkacz been more precise in expressing his ideas, I would have been able to conclude my critical evaluation of his paper more quickly.

Get your facts straight please, Professor!

I do, however, have one major complaint that I'd like to make, before addressing the substance of Professor Tkacz's article. If you're going to attack Intelligent Design - or more precisely, the "God-of-the-gaps" version of Intelligent Design - then intellectual honesty demands that you represent it accurately in the first place. I have to say that Professor Tkacz makes no effort to do this. What he offers the reader is a caricature of Intelligent Design, designed to make it look silly. The model of God which he imputes to ID is an unrecognizable "straw man": a time-bound Deity who designs a world, subsequently realizes that His original design wasn't good enough to produce life in all its complexity, and then periodically intervenes to fix the flawed world He has made, by creating various life-forms. The loaded terms which he employs when ridiculing ID don't help matters, either.

In both his original talk to the Gonzaga Socratic Club, and the revised version of his talk, published in This Rock, Professor Tkacz depicts ID proponents as theological simpletons, who hold that God "intervenes in nature," that God acts on nature "the way a human being might act on an artifact to change it," that "nature, as God originally created it, contains gaps or omissions that require God to later fill or repair," that God "has periodically produced new and distinct forms of life," and even that God "reaches into" pregnant hippopotamuses "to cause them to give live birth"! However, the accusation of anthropomorphism which Professor Tkacz hurls at the ID movement is totally inaccurate, as I will attempt to show.

*****************************************

2. TKACZ'S FOUR MAJOR MIS-REPRESENTATIONS

Major Mis-Representation Number One

Major Mis-Representation Number Two

Major Mis-Representation Number Three

Major Mis-Representation Number Four

Major Mis-Representation Number One: ID is NOT committed to God "intervening" in Nature

The Greek playwright Euripides (c.480-406 B.C.) frequently employed the Deus ex Machina device in his tragedies. Shakespeare also used the device in As You Like It, Pericles, Prince of Tyre, and The Winter's Tale. ID proponents are often accused of holding that God "intervenes" in Nature, in the way that a Deus ex Machina used to, in Greek and Roman plays.

Contrary to what Tkacz asserts, ID proponents are not committed to holding that God "intervenes in nature," for the simple reason that the notion of God "intervening" makes no sense. As Fr. Brian Davies, O.P. (who is no friend of ID), pointed out in a recent talk he gave on the New Atheism, you can only "intervene in" a situation from which you were absent in the first place. Since God is everywhere, upholding all things by the power of His Word, He can't properly be said to "intervene in" any situation.

What many ID proponents do maintain is that God is capable of producing changes in creatures without using secondary causes, and that He has in fact done so. As we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 2 and "Smoking Gun" number 3 (in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz), Aquinas says that too.

*****************************************

Major Mis-Representation Number One

Major Mis-Representation Number Two

Major Mis-Representation Number Three

Major Mis-Representation Number Four

Major Mis-Representation Number Two: ID proponents do NOT claim that God "created" biological structures exhibiting specified complexity

Diagram showing how the translation of the mRNA and the synthesis of proteins is made by ribosomes. Courtesy of Mariana Ruiz Villarreal ("Lady of Hats"), Wikipedia. The ribosome is an excellent example of specified complexity. It is obviously the product of Intelligent Design.

Nor are ID proponents committed to the view (which Professor Tkacz imputes to us) that God "created" biologically complex structures. As Tkacz rightly points out, the word "create" has a very precise meaning for Aquinas: to "create" something means to cause its very being, and not just its form. Thus creation does not presuppose any raw material; in that sense, it is "out of nothing" (ex nihilo). Indeed, even if the world had no beginning, Aquinas would still say that God creates it, in the sense that He maintains it in existence, and were He not to do so, it would instantly cease to exist.

A form, on the other hand, is something realized in matter. Hence the production of a new form in pre-existing matter would not constitute an act of creation for Aquinas. Is this a problem for Intelligent Design? Not at all. In Thomistic terminology, what theistic ID proponents are claiming is that those biological structures which exhibit the property of specified complexity were produced immediately by God. That's the phrase Aquinas uses when describing the production (not creation) of the human body of Adam, from pre-existing slime. In his Summa Theologica I, q. 91 art. 2 Aquinas asks whether the human body (of the first man) was "immediately produced by God," and answers in the affirmative:

I answer that, The first formation of the human body could not be by the instrumentality of any created power, but was immediately from God.

Here's another phrase Aquinas uses, when describing how the forms of the "higher" animals - or "perfect" animals, as Aquinas calls them - were first produced: "the primary establishment of these forms ... must of necessity proceed from the Creator alone" (see his Summa Contra Gentiles Book II chapter 43, paragraph 6). So what ID proponents like myself are claiming is that the original production of biological forms exhibiting the property of specified complexity must, of necessity, proceed from the Creator alone. Is that precise enough for you, Professor Tkacz?

What "God-of-the-gaps"-style ID proponents like myself are saying, then, is that complex biological forms, whose specified complexity exceeds a certain threshold, were produced immediately by God. Production of a new form in pre-existing matter would be described as a change by Aquinas, rather than an act of creation, and ID proponents are perfectly happy to refer to it as a change. However, Professor Tkacz appears to think that he can hang the entire Intelligent Design movement on the basis of a terminological distinction which he alleges we fail to make: the distinction between an act of creation and a change. As he puts it in his talk:

Thomas points out that the judgment that there is a conflict here results from confusion regarding the nature of creation and natural change. It is an error that I call the "Cosmogonical Fallacy." Those who are worried about conflict between faith and reason on this issue fail to distinguish between cause in the sense of a natural change of some kind and cause in the sense of an ultimate bringing into being of something from no antecedent state whatsoever. "Creatio non est mutatio," says Thomas, affirming that the act of creation is not some species of change......It would seem that Intelligent Design Theory is grounded on the Cosmogonical Fallacy. Many who oppose the standard Darwinian account of biological evolution identify creation with divine intervention into nature. This is why many are so concerned with discontinuities in nature, such as discontinuities in the fossil record: they see in them evidence of divine action in the world, on the grounds that such discontinuities could only be explained by direct divine action. This insistence that creation must mean that God has periodically produced new and distinct forms of life is to confuse the fact of creation with the manner or mode of the development of natural beings in the universe. This is the Cosmogonical Fallacy.

Curiously, the phrase, "Creatio non est mutatio," (Creation is not change) is the only quotation from Aquinas in Professor Tkacz's entire talk. I find it very curious that he cites it in Latin (was that intended to make it sound more impressive, I wonder?) and that he gives no reference for his citation. Interested readers can find the quote in Aquinas' Summa Contra Gentiles Book II, chapter 17, where he argues that creation is neither a movement nor a change.

In any case, it should be clear by now that Professor Tkacz's theological criticism of the Intelligent Design movement is wide of the mark. ID proponents are interested in identifying changes in Nature which are unambiguously the work of an Intelligent Agent, in order to overturn the reigning scientific paradigm, that mindless forces are sufficient to explain the world around us. That's why Intelligent Design proponents are interested in "discontinuities" in Nature, among other things. But we do not hold that these changes are the way in which God creates things. We're quite happy to use Aquinas' word, "produce," and many ID proponents would add that patterns in Nature exhibiting a certain level of specified complexity were "produced immediately by God," as St. Thomas puts it.

*****************************************

Major Mis-Representation Number One

Major Mis-Representation Number Two

Major Mis-Representation Number Three

Major Mis-Representation Number Four

Major Mis-Representation Number Three: ID proponents do NOT claim that God acts on nature in exactly the same way as an artist acts on an artifact

St. Gregory Nazianzen. Fresco from Kariye Camii, Istanbul, Turkey. St. Gregory Nazianzen was a 4th century Archbishop of Constantinople and theologian, who likened God's creation to an ancient musical instrument (a lute). "For every one who sees a beautifully made lute, and considers the skill with which it has been fitted together and arranged, or who hears its melody, would think of none but the lutemaker, or the luteplayer, and would recur to him in mind, though he might not know him by sight. And thus to us also is manifested That which made and moves and preserves all created things, even though He be not comprehended by the mind." (Oration XXVIII, paragraph VI.) Many ID proponents actually prefer St. Gregory's "lute" analogy of the universe to Paley's "watch" analogy. But of course, no analogy is perfect.

Professor Tkacz also implicitly accuses ID proponents of holding that God acts on nature "the way a human being might act on an artifact to change it." Even if he's just talking about "God-of-the-gaps"-style ID proponents like myself, he's simply wrong here. To be sure, many ID proponents have likened God to an artist or craftsman. So what? Aquinas does too - for instance, when he writes in his Summa Theologica I-II, q. 1 art. 2 (Whether it is proper to the rational nature to act for an end?):

For the entire irrational nature is in comparison to God as an instrument is to the principal agent, as stated (I, Q, 22, a. 2, ad 4; I, Q. 103, a. 1, ad 3). Consequently it is proper to the rational nature to tend to an end, as directing [agens] and leading itself to the end: whereas it is proper to the irrational nature to tend to an end, as directed or led by another...

But all analogies have to be used with caution: there are both similarities and differences between God's relation to Nature and a human being's relation to an artifact. Here are three obvious differences: (i) God created Nature, but human beings don't create artifacts - they merely shape them from pre-existing material; (ii) God can act on Nature directly without doing any violence to it, whereas a human craftsman has to employ some degree of force to get his raw material into the shape he/she wants; and finally, (iii) human artifacts can only be good in relation to some extrinsic end, whereas God's creatures - especially living creatures - can also have a good of their own (intrinsic finality).

Now here are three similarities between God's relation to Nature and a human being's relation to an artifact: (i) Nature is an expression of God's will, just as a work of art is an expression of the artist's will; (ii) everything in Nature contributes to the perfection of the cosmos as a whole, just as the various features of a work of art were all put there in order to realize an end intended by the artist; and finally, (iii) God is perfectly free to act immediately on Nature whenever He wishes to do so, just as an artist is free to interact directly with his/her work of art.

The world is an expression of God's intellect as well as God's will. Here again we can see an obvious similarity between God and a human artist. An artist knows what he/she wants to produce, and God knows what effects He wants to bring about in the natural world. Now here is where the discussion starts to get interesting. Is it anthropomorphic to ascribe "intellect" to both God and a human artist? Does the term "intellect" have the same meaning in both cases? I'd answer "No" to the first question, and "Yes" to the second. The intellect is simply that which understands things - i.e. knows what they are - and I would personally maintain that the verb "know" has the same meaning when applied to God and humans. Some very famous Christian philosophers and theologians, such as St. Anselm (c. 1033-1109) and Duns Scotus (c.1265-1308), have argued that since "knowledge" is a pure perfection, which does not impose any limitations on its possessor, the term "knowledge" must have the same meaning for God and creatures alike: it can be applied univocally to both. (In this respect, knowledge is unlike the perfection of "rationality," which is limiting because it requires its possessor to arrive at a conclusion only after reasoning his/her way from premises.) Thus although the manner in which God knows is utterly different from our own, and although God's knowledge is infinitely greater than ours in degree, the actual meaning of the word "know" is the same for God as it is for other intelligent beings.

Aquinas (1225-1274) took a slightly different view from St. Anselm and Duns Scotus. He maintained that the word "know" is only used analogically when applied to God. For Aquinas, the statement, "God is intelligent" simply means: "There is something in God which is to God like intelligence is to human beings." Putting it mathematically,

X: God = Intelligence: Human beings.

Additionally, God is the cause of knowledge in human beings, where the causal relationship is an intrinsic one, which brings about a similarity in the effect (intrinsic analogy of attribution).

Duns Scotus wasn't satisfied with this explanation. Saying that X is to God what intelligence is to a human being tells me nothing about X, if I don't already know what God is. Also, there's no point in saying that my intelligence is like God's if I don't know what "like" means. But as I'm sure Professor Tkacz is well aware, the differences between Aquinas and Duns Scotus on this issue have been greatly exaggerated. Moreover, in formulating his doctrine of univocal predication, Scotus was opposing the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas, but those of the theologian Henry of Ghent. And speaking of Aquinas, here is what he wrote in his Summa Contra Gentiles Book II, chapter 46, paragraph 4, about why the cosmos would have been lacking in perfection if God had not made intelligent creatures:

[T]he highest perfection of things required the existence of some creatures that act in the same way as God. But it has already been shown that God acts by intellect and will. It was therefore necessary for some creatures to have intellect and will.

Duns Scotus couldn't have put it better himself.

If we bear all these similarities and differences in mind between God and human designers, then the assertion made by various ID proponents, that some forms in Nature were originally produced immediately by God alone, in a manner similar to the way in which a work of art is produced by an artist, will no longer sound anthropomorphic.

*****************************************

Major Mis-Representation Number One

Major Mis-Representation Number Two

Major Mis-Representation Number Three

Major Mis-Representation Number Four

Major Mis-Representation Number Four: ID proponents do NOT claim that God creates nature and then fills in the gaps later, as an afterthought

"Kairos," by Francesco Salviati. Palazzo Sacchetti, Rome, 1552-1554. Courtesy of Wikipedia and the Yorck Project.

"Kairos" is an ancient Greek word meaning the right or opportune moment. In the New Testament, kairos means "the appointed time in the purpose of God", the time when God acts (e.g. Mark 1:15, "The kairos is fulfilled.") It differs from the more usual word for time, which is chronos (kronos).

There's just one more mis-representation I'd like to take Professor Tkacz to task for. Even "God-of-the-gaps"-style ID proponents (such as myself) do not hold that "the view that nature, as God originally created it, contains gaps or omissions that require God to later fill or repair," as Professor Tkacz accuses us of doing in the revised version of the talk he gave to the Gonzaga Socratic Club. God is outside time; there is no "before" and "after" with Him. God is also omniscient: He doesn't have "after-thoughts." What ID proponents like myself hold is that God, in creating the universe with its laws of nature, its natural constants and its initial conditions, did not thereby specify every event that was to follow, in the long history of the universe. In particular, God did not specify the subsequent emergence of structures exhibiting specified complexity in the Big Bang. That's because He never intended to - and for a very good reason, which we'll discuss below. (The curious reader can find the explanation in "Fatal Flaw Number Four".) To ensure the emergence of these structures, God timelessly decided to supplement His initial specification of the cosmos with some additional acts, involving the immediate production of biological forms exhibiting specified complexity, without the use of any secondary causes. From our (time-bound) perspective, then, God produced these forms after the Big Bang, but from God's perspective, all of these acts were part of His timeless plan for creation.

Likewise, the view which Professor Tkacz ascribed to ID proponents in his speech to the Gonzaga Socratic Club, namely, that "God has periodically produced new and distinct forms of life," is at best an ambiguous statement, as it could be interpreted to mean that God acts periodically (i.e. from time to time), which is obviously false, as God is outside time. It would be better to say that from time to time, new and distinct forms of life instantiating the property of specified complexity have appeared on Earth, and that these forms were produced immediately by God, Who is outside time.

Putting it another way: many Intelligent Design theorists (including myself) would maintain that at certain points in time, Nature is manipulated by God. Indeed, we'd go so far as to say that Nature is made to be manipulated. However, this does not entail that God manipulates Nature at certain points in time. God is outside time; when He manipulates Nature, He does so timelessly.

OK. Enough griping on my part; time to get down to tin tacks.

*****************************************

Despite its stylistic virtues, Professor Tkacz's paper is marred by five fatal flaws. I'm going to point out these flaws, and after reading this post, I hope that readers will agree that Professor Tkacz's thinking differs profoundly from that of St. Thomas Aquinas, on matters relating to the origin of living things.

*****************************************

Fatal Flaw Number One

Fatal Flaw Number Two

Fatal Flaw Number Three

Fatal Flaw Number Four

Fatal Flaw Number Five

Fatal Flaw Number One: Tkacz's Personification Of Nature As One Big Autonomous Agent

Central part of a large floor mosaic, from a Roman villa in Sentinum (now known as Sassoferrato, in Umbria, Italy), ca. 200–250 C.E. Aion, the god of eternity, is standing inside a celestial sphere decorated with zodiac signs, in between a green tree and a bare tree (summer and winter, respectively). Sitting in front of him is the mother-earth goddess, Tellus (the Roman counterpart of Gaia) with her four children, who possibly represent the four seasons.

The first fatal flaw in Professor Tkacz's critique of ID is his outrageous personification of Nature as "she." He isn't just waxing poetic here; he really does regard Nature as One Big Agent. What's more, Nature is One Big Autonomous Agent, according to Professor Tkacz. While Nature is totally dependent on God for her being, Nature's operations are entirely her own. God never "interferes" with the operations of Nature; He is "responsible for" them only insofar as He is the Creator of Nature. God alone can cause things to exist, and the universe would be nothing without Him. Hence Creation is God's domain. Change, however, is entirely Nature's domain. Nature alone produces all the changes in the world, without God needing to "intervene." Indeed, Tkacz even enunciates a Great Principle of his own, which is nowhere to be found in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas - the principle of the Autonomy of Nature, as he calls it. Here is how he explains it:

...[N]ature and her operations are autonomous in the sense that nature operates according to the way she is, not because something outside of her is acting on her. God does not act on nature the way a human being might act on an artifact to change it. Rather, God causes natural beings to be in such a way that they work the way they do... Why are there such things as Hippopotamuses? Well, nature produced them in some way. What way did nature produce them and why does nature produce things in this way? It is because God made the whole of nature to operate in this way and produce by her own agency what she produces.

As I read him, Professor Tkacz is saying that God does not act on Nature, except in order to maintain it in existence. But some readers might ask: is that a fair summary of Tkacz's position? After all, doesn't he immediately qualify his assertion that "God does not act on nature" with the words "in the way a human being might act on an artifact to change it"? However, I don't think Professor Tkacz intended these words to qualify his assertion - as we saw above, he seems to have added them purely for the sake of taking a cheap swipe at Intelligent Design. But there's more. Earlier in his paper, Professor Tkacz draws a sharp distinction between the being of a thing and its operations, and he expressly states that "God causes natural beings to exist in such a way that they are the real causes of their own operations." That sounds pretty clear to me. Later, when discussing the case of hippopotamuses giving birth, Tkacz limits God's causal role to His creating (i.e. bringing into existence and maintaining in existence) the whole of Nature (including hippopotamuses), such that these animals have the genetic and anatomical features that cause them to give birth. Then Tkacz adds: "It cannot be that God 'reaches into' the normal operations of hippopotamuses to cause them to give live birth."

Professor Tkacz is even clearer in his more recent 2008 article, Aquinas vs. Intelligent Design:

God does not intervene into nature nor does he adjust or "fix up" natural things...Thus, the evidence of nature's ultimate dependency on God as Creator cannot be the absence of a natural causal explanation for some particular natural structure. Our current science may or may not be able to explain any given feature of living organisms, yet there must exist some explanatory cause in nature.

"Cannot be," "must exist" - note the dogmatism here. On Professor Tkacz's view, then, Nature is autonomous, and changes occurring in Nature cannot be directly caused by God. God creates Nature, and maintains it in being, but does not immediately act on it - for that would constitute interference.

But as we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 2 and number 3 in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz, Aquinas explicitly taught that it is perfectly appropriate for God to produce effects in the natural world without using any secondary causes, if He wishes to do so; and additionally, there are some physical changes (such as the production of the first human body from inanimate matter, and the production of the first animals, according to their various kinds), which could only have been produced by God alone.

Finally, unlike Professor Tkacz, Aquinas did not make the mistake of treating Nature as One Big Agent. Nor did he regard Nature as autonomous. As we saw from the quotes above, Professor Tkacz likes to talk about how Nature "operates," and how Nature "produces" "her" effects. (Note: the capitalization of Nature is mine - VJT.) But what does Aquinas say? When searching through the Summa Theologica and the Summa Contra Gentiles for the phrases "nature act(s)," "nature operate(s)" and "nature produce(s)," I came up with a meager handful of phrases, none of which support Professor Tkacz's grand claim that Nature can be viewed as One Big Agent, who is autonomous in her operations. Here is what I found:

Summa Theologica I, q. 19, art. 4 (Whether the will of God is the cause of things):

Since both intellect and nature act for an end, as proved in Phys. ii, 49, the natural agent must have the end and the necessary means predetermined for it by some higher intellect; as the end and definite movement is predetermined for the arrow by the archer.

Summa Theologica I q. 118 art 2, ad. 3 (Whether the intellectual soul is produced from the semen?):

Now it is manifest from what has been said above (105, 5; 110, 1) that the whole of corporeal nature acts as the instrument of a spiritual power, especially of God.

Summa Theologica I-II. q. 1 art. 2 (Whether it is proper for the rational nature to act for an end?):

On the contrary, The Philosopher proves (Phys. ii, 5) that "not only mind but also nature acts for an end."I answer that, Every agent, of necessity, acts for an end... But an agent does not move except out of intention for an end. For if the agent were not determinate to some particular effect, it would not do one thing rather than another..

Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 75, paragraph 8 (That God's Providence Applies to Contingent Singulars):

[8] ... Moreover, good uses of these cannot fail to be made, except in rare instances, because things that are from nature produce their effects in all cases, or frequently. Thus, it is not possible for all individuals to fall, even though a particular one may do so.

Summa Contra Gentiles Book IV, chapter 81, paragraph 5 (Solution of the Objections Mentioned [to the doctrine of the Resurrection]):

[5] ... But the divine power which produced things in being operates by nature in such wise that it can without nature produce nature's effect, as was previously shown.

There are some beautiful quotes here by Aquinas, which would cheer the heart of any creationist or Intelligent Design theorist. I especially liked the one where St. Thomas wrote that "the whole of corporeal nature acts as the instrument of a spiritual power, especially of God." But there is nothing in the quotations listed above which even remotely suggests that Aquinas viewed Nature as One Big Agent, let alone One Big Autonomous Agent. Even when Aquinas writes that "nature acts for an end," he immediately follows it with an explanation restating his claim as an assertion about each and every natural agent: "Every agent, of necessity, acts for an end." The only time when Aquinas is genuinely enthusiastic when speaking of Nature holistically is when he speaks of it as God's instrument - which means that Nature is not autonomous, after all.

Nor will Aquinas' oft-repeated phrase, "Nature does nothing in vain," be of any help to Professor Tkacz. For as we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 14 in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz, Aquinas often quotes other versions of the same saying, which refute any claim that Aquinas viewed Nature is One Big Autonomous Agent. For instance, he writes that "God and nature make nothing in vain," "God and nature do nothing in vain," "God makes nothing in vain," "None of God's works have been made in vain," and "Nothing in nature is in vain." Viewed against this context, it can no longer be seriously maintained that Aquinas envisaged Nature as autonomous.

*****************************************

Fatal Flaw Number One

Fatal Flaw Number Two

Fatal Flaw Number Three

Fatal Flaw Number Four

Fatal Flaw Number Five

Fatal Flaw Number Two: Tkacz's Assumption That Natural Entities Must Proceed From Natural Causes, Or Their Nature Would Be Unintelligible

God creating the land animals (Vittskovle Church fresco, Denmark, 1480s).

The second fatal flaw in Professor Tkacz's critique of ID is related to the first. Tkacz argues that we cannot understand a natural entity properly unless we know its natural mode of generation, and then argues that since natural things are intelligible, they must be understood in terms of their natural causes. Taken to its logical conclusion (and I assume Professor Tkacz wouldn't want to take it this far), this rules out a supernatural cause for any natural entity - which means that God could not have produced animals or other living things immediately, even if He wanted to. Ditto for the production of Eve from Adam's side, and for that matter, the Virginal Conception of Jesus.

Yet, the evidence for God's Creation of the natural universe is the known fact - a fact that we know on the basis of our scientific research - that natural things are intelligible. If they are intelligible, they are so as the products of nature - that is, they are intelligible in terms of their natural causes.

But what Aquinas argues is something quite different. While he does indeed argue that in order to properly understand what a certain kind of natural object is (say, a hippopotamus) we need to understand its natural mode of generation, he does not conclude that each and every entity belonging to that kind must be produced naturally. Nor does he conclude that the entity would no longer be intelligible if it were produced supernaturally. Instead, what Aquinas concludes is that ifan entity of that kind has a natural origin (as it usually does), then it must have been produced in a certain specific way, i.e. from a particular kind of matter, according to its natural mode of generation. But this in no way rules out the possibility of an entity of that kind being produced supernaturally. Indeed, as we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 6, Aquinas explicitly states that a natural entity can be generated supernaturally, whenever God wishes to do so, and that it does not thereby become a different kind of object.

*****************************************

Fatal Flaw Number One

Fatal Flaw Number Two

Fatal Flaw Number Three

Fatal Flaw Number Four

Fatal Flaw Number Five

Fatal Flaw Number Three: Tkacz's "Mere Conservationism" vs. Aquinas' Maximally Active Deity

Left: A gray hippopotamus at Lisbon zoo. Courtesy of Joaquim Alves Gaspar.

Right: A Nine-banded Armadillo in the Green Swamp, central Florida. Courtesy of Tom Friedel at BirdPhotos.com.

Professor Tkacz uses the birth of a hippopotamus to argue against concurrentism; while Professor Alfred Freddoso uses the birth of an armadillo to illustrate his argument (scroll down to pages lxxxviii and lxxxix) for concurrentism. Concurrentism is a model of how God acts in the world. Aquinas espoused it; whereas Professor Tkacz rejects it, in favor of another model, called "mere conservationism."

The third fatal flaw in Professor Tkacz's attack on ID is that his own model of Divine agency is totally un-Thomistic. In a nutshell: Professor Tkacz is a "mere conservationist," whereas Aquinas is a concurrentist. This distinction is a very important one for ID, as we'll see below: Aquinas' concurrentism is ID-friendly, while "mere conservationism" rules out all but the extreme "front-loading" version of ID. I would like to acknowledge my indebtedness to Professor Alfred Freddoso for the account that follows, and if there are any errors in my exposition, then I take full responsibility for them. (For a succinct summary of the issues involved, see here, where Professor Freddoso uses the term "weak deism" to designate the view that he later, and more charitably, came to call "mere conservationism." For two longer essays of his, defending concurrentism against mere conservationism, see here and here.)

Professor Tkacz believes that whenever a natural agent produces some effect (e.g. when a flame heats a piece of metal, causing it to glow), its actions are entirely its own, springing from the nature and capacities which God gave it. God's role is limited to conserving the agent in being - hence the term, "mere conservationist." And although Professor Tkacz also says that "God is totally and immediately present as cause to any and all processes," all he means by this assertion is that "God causes natural beings to exist in such a way that they are the real causes of their own operations," as he declares later in his talk. In the following extracts from Professor Tkacz's talk, Tkacz focuses on one particular natural change - the birth of a baby hippopotamus - to illustrate his point. Readers should bear in mind the fact that Tkacz uses the term "create" to mean not only "bring into being," but also "maintain in being":

[M]odern Thomists distinguish between the existence of natural beings and their operations. God causes natural beings to exist in such a way that they are the real causes of their own operations...

Let me just jump in here with a quick critical observation. Tkacz's assertion that natural beings are "causes of their own operations" is philosophically absurd, as it generates an infinite regress. The act of causing an operation is itself an operation, which means that there must be an operation of causing that, and so on ad infinitum. Perhaps Professor Tkacz has a response to this argument; if so, I'd like to hear it.

Getting back to the birth of the baby hippopotamus:

Consider another example: a large quadrapedic (sic) mammal, such as a hippopotamus, gives live birth to its young. Why? Well, we could answer this by saying that "God does it." Yet, this could only mean that God created hippopotamuses - indeed the mammalian order, the whole animal kingdom, and all of nature - such that these animals have the morphology, genetic make-up, etc. that are the causes of their giving live birth. It cannot be that God "reaches into" the normal operations of hippopotamuses to cause them to give live birth. Were one to think that "God does it" must mean that God intervenes in nature in this way, one would be guilty of the Cosmogonical Fallacy.Now, if this distinction between the being of something and its operation is correct, then nature and her operations are autonomous in the sense that nature operates according to the way she is, not because something outside of her is acting on her.

As I understand him (and I've read and re-read his talk scores of times to make sure I'm not mis-representing him), Professor Tkacz is saying that when a pregnant hippopotamus gives birth, God does not do anything to make her give birth as such. Rather, God simply makes her to be a hippopotamus, period. And giving birth to live young - rather than young that hatch from eggs, as birds do - after getting pregnant, is simply part and parcel of what it is to be a hippopotamus. According to Tkacz, God, Who is timeless, created hippopotamuses (presumably, through the process of evolution), and God timelessly maintains each hippopotamus in being - and that's all He does. In particular, God does not act on Nature (even timelessly) to ensure that this hippopotamus gives birth, when she does - for that would be interference with the Autonomy of Nature. Nature's being is sufficient to explain "Her" operations. Or as Professor Tkacz puts it, "nature operates according to the way she is, not because something outside of her is acting on her." If this is not a clear statement of "mere conservationism," then I don't know what is. And without "mere conservationism," Professor Tkacz's whole case against Intelligent Design collapses - for conservationism's main rival, concurrentism, is perfectly compatible with Intelligent Design.

I also noticed that Professor Tkacz said not a word about powers when putting forward his distinction between the being of a thing and its operations. Indeed, he doesn't use the word "power" even once during his talk. How extremely odd. This is a very striking omission. I wonder if "modern Thomists" still believe in powers. I hope so!

In any case, Professor Tkacz apparently believes he has St. Thomas' support for his "mere conservationist" views, for in the revised version of his talk, he writes:

According to Thomism, God is indeed the Author of nature, but as its transcendent ultimate cause, not as another natural cause alongside the other natural causes.

This quote from Professor Tkacz is a perfect example of two recurring argumentative faults of his: firstly, his inability to state his opponents' views fairly, and secondly, his utterly baseless imputation to St. Thomas Aquinas of opinions which run counter to what Aquinas actually believed. Firstly, no-one holds that God is a "natural cause," so why waste time attacking that straw man? The question I wish to address in this post is whether God, in addition to being the transcendent Author of Nature who maintains it in being, is also a Supernatural Cause who works alongside natural causes, whenever they operate. It is most unfortunate that Professor Tkacz cannot bring himself to state this view fairly, even in order to criticize it.

Secondly, as I documented in detail in the long version of "Smoking Gun" number five, in Part One of my response to Professor Tkacz, Aquinas and the vast majority of medieval philosophers believed that whenever a natural agent produces some effect, God always acts in co-operation with it, as a Supernatural Agent, so that both God and the natural agent are immediate causes of the effect they produce. Indeed, no natural agent can do anything unless God co-operates with it, bringing about the change together with the agent. This model of Divine agency is known as concurrentism. As I'll explain below, it's a very ID-friendly view of Divine agency.

Before we go further, I suggest that readers might want to review the long version of "Smoking Gun" number five, in Part One of my response to Professor Tkacz, to familiarize themselves with Aquinas' concurrentism. To clear up any remaining misunderstandings, I'd like to respond to five quick questions I imagine my readers will want to ask.

Question 1: "You mean, God does half the work and the natural agent does the other half?"

Answer: No. God and the natural agent operate on different levels, and they each do 100% of the work on their respective levels. God acts as a Transcendent cause, while the natural agent is a created cause. God is not merely the first in a long chain of causes; rather, God is above the entire chain, actively co-operating with each and every member as it produces its effect.

Question 2: "But if God and the natural agent both cause the same effect, isn't this unnecessary duplication?"

Answer: No. God and the natural agent contribute to the change they produce in different ways. Let's say that God and natural agent A (e.g. a flame) co-operate to make agent B (e.g. a piece of metal) do something new (e.g. glow). In this case, God causes agent B (the piece of metal) to do something, while natural agent A causes it to do this (glow). Agent A is responsible for the specificity of the effect (the glowing), while God acts as a universal cause, responsible for the occurrence of the effect (the glowing). Both contributions are essential; and each is nothing without the other.

Question 3: "So there are two actions resulting in the same effect, then - God's transcendent action and the creature's action at the natural level?"

Answer: No. God and the natural agent co-produce their effect by a single action, because actions are individuated by their effects, rather than their causes. As Professor Freddoso has pointed out, this is an axiom of Scholastic theology.

Question 4: "So if the creature does something bad or harmful, then isn't God is a 'partner in crime' with the creature? Doesn't this make Him responsible for evil?"

Answer: No. As we saw, God is a universal cause. When God co-operates with a natural agent (e.g. the flames of a forest fire) that causes a harmful effect (e.g. the death of an animal, which is a natural evil), we have to distinguish between the general features of the effect (e.g. the fact that fires burn combustible bodies in their path) and the particular details (e.g. the fact that the fire burned this unlucky animal). As a universal cause, and as the Author of Nature, God is morally responsible for the former, but not the latter. Of course, some people might still try to find fault with God for making flames which are liable to burn animals in the first place, or for making some animals too slow to run away from approaching forest fires. But that's a problem for "mere conservationists" like Professor Tkacz, just as much as it is for concurrentists like Aquinas. And the Scholastic answer to this problem would be that: (a) the tendency of flames to burn flesh is not evil per se; (b) because natural processes are inherently liable to fail on the odd occasion, some individual animals will necessarily have defects (e.g. lameness), which may cost them their lives in a forest fire; and (c) asking God to guarantee that animals should always be out of harm's way whenever a forest fire rages, is tantamount to asking Him to act as a Cosmic Nanny. For God to prevent all these harms would constitute an excessive restriction on the "creatureliness" of creatures: it would "cramp their style" too much.

Question 5: "If the creature is a moral agent, who does something bad or harmful, then why isn't God responsible for the evil done by that agent?"

Answer: When God co-operates with a moral agent, who has a will of his/her own, God is in no way responsible for the moral evil of that agent's act, as this defect from the agent. For instance, when Brutus stabbed Caesar, God, in co-operating with Brutus, intended that his hands should work as they normally would when picking up things (be they spoons, gifts or daggers), and that the dagger held by Brutus should remain in his hand as it normally would when held firmly. What God did not intend was that Brutus should stab Julius Caesar with this dagger. In the words of Aquinas, "Forasmuch as the first cause has more influence in the effect than the second cause, whatever there is of perfection in the effect is to be referred chiefly to the first cause: while all defects must be referred to the second cause which does not act as efficaciously as the first cause" (Quaestiones Disputatae De Potentia Dei (Disputed Questions Relating to the Power of God) Q. III art. VII, Reply to Objection 15). Hence God is in no way the Author of evil.

Concurrentists believe that God's agency, when producing a natural effect, is immediate in another sense, as well: God uses the natural agents He co-operates with as instruments of His will, in order to accomplish the effect He intends. In these cases, God is primarily responsible for the effect as its Author, and the natural agent plays a subsidiary role. Because the effect brought about is intended as an end by God, who planned it to happen, then we can legitimately speak of it as being immediately brought about by God. I have already discussed this sense of immediacy at considerable length, in the long version of "Smoking Gun" number five, in Part One of my response to Professor Tkacz. I showed there that Aquinas explicitly taught that God uses the natural agents He co-operates with as instruments of His will, and that when He does so, His agency is immediate.

"But why does it matter whether God co-operates with each and every natural agent, when it acts?" I hear you ask. Here's why. If you're a "mere conservationist" like Professor Tkacz, then you'll believe that God could only stop a natural agent from behaving as it normally does by "intervening in" or "interfering with" Nature. That sounds messy. Miracles are problematic too, for the same reason: it seems repugnant that God should have to interfere with His own handiwork, in order to bring about a desired effect. No wonder "mere conservationists" want to keep miracles as rare as possible.

A "mere conservationist" can believe in Intelligent Design, but only the extreme front-loading variety, whereby God programs the specifications for complex biological structures into the initial conditions of the Big Bang - or perhaps creates a very peculiar set of highly specific, information-rich laws - utterly unlike the general, information-poor laws we know - which lead inexorably to the emergence and subsequent evolution of life when the right sequence of events unfolds. Either way, though, it's very fiddly work for the Deity, so I'm not surprised that few "mere conservationists" entertain this option seriously.

But if you're a concurrentist, then you'll have no problem believing in miracles or Intelligent Design. Miracles are elegantly simple for God to accomplish, on a concurrentist view. God never has to "go against" a natural agent when He works a miracle, even if it's a miracle that's "contrary to nature": all He has to do is refuse to co-operate with the agent in the way that He normally does. Take the Biblical account of Shadrach surviving unharmed in Daniel's fiery furnace (Daniel 3:26-27). In order to stop the flames from burning Shadrach, all God had to do was "turn off the taps" on His side, by refraining from co-operating with the flame when it came into contact with Shadrach's body. The flames still retained their natural disposition to burn (as shown by the fact that they incinerated Nebuchadnezzar's soldiers), but they couldn't do anything to Shadrach without God's co-operation.

I should add that concurrentism accords perfectly well with a philosophically rigorous, scientifically adequate account of the laws of nature. Readers who would like to know more can check out this essay by Professor Freddoso.

Intelligent Design isn't a problem either, if you're a concurrentist. God already has His finger in every pie, for no natural agent can do anything without Him. And if God chooses to supplement His normal co-operation with natural agents with some special effects that are produced by Him alone, that's His business. On a concurrentist view, there's absolutely no reason why He shouldn't produce some special effects in Nature on His own, if He wants to. He's not interfering with Nature, because He's already in the thick of things: He works with each and every natural agent, whenever it acts.

This argument ties in with another reason why concurrentism should be especially attractive to religious believers: it offers us a maximally active Deity, one Who causes every effect, whether acting alone or acting in co-operation with creatures. By contrast, "mere conservationism" keeps God on a tight leash: although He keeps every kind of creature in being, He does not co-operate with any creature when it acts; nor does He "intervene in nature" (to use Professor Tkacz's dreadful phrase), for that would be interfering with Nature's autonomy. At the same time, concurrentism upholds the view that creatures are maximally active: since they participate in the agency of God their Creator, who is Pure Act, it is only fitting that they should be as active as created beings can possibly be.

Concurrentism thus stands mid-way between two extreme views of how God interacts with the world: a view that mistakenly minimizes God's agency, in order to maximize not only the agency of creatures, but also their autonomy ("mere conservationism"), and another bizarre view called occasionalism, which maximizes God's agency at the expense of creatures. According to this view, creatures don't really act at all. Even though they appear to act in certain situations, it's really God who's acting on all those occasions when they happen to be around. Thus a flame doesn't really burn; God just goes into "burn mode" when something which God has deemed "combustible" gets sufficiently close to a flame. St. Thomas considered this view to be absurd and unscientific, as we would have no way of knowing things' natures if they could not act:

And thus, all the knowledge of natural science is taken away from us, for the demonstrations in it are chiefly derived from the effect. (Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 69, paragraph 18.)

Additionally, St. Thomas argued that "if no creature has any active role in the production of any effect, much is detracted from the perfection of the creature," and that "this position detracts from the divine power" as well, because it entails that God is unable to communicate the perfection of agency to creatures (Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 69, paragraph 15). Hence occasionalism limits both God and creatures.

So I would like to counter Professor Tkacz's Principle of the Autonomy of Nature with a principle, which I call the Principle of Maximal Activity: we should ascribe the maximum possible degree of agency to God and creatures alike. Or as Professor Alfred Freddoso puts it in his essay, God's General Concurrence With Secondary Causes: Why Conservation Alone Is Not Enough: "in general, theistic naturalists should be antecedently disposed to countenance in nature the maximal degree of divine activity compatible with the thesis that there is genuine secondary causation." Concurrentism is the only account of Divine Agency which satisfies these criteria, as it asserts that God co-operates with every natural agent, making Him an immediate cause of each effect, while creatures retain their natural agency. Concurrentism thus maximizes the activity of both God and creatures.

I presume that Professor Tkacz is familiar with concurrentism. His example of a hippopotamus giving birth sounds suspiciously similar to the example of the birth of a baby armadillo, discussed by Professor Alfred Freddoso, of Notre Dame University in his essay, God's General Concurrence with Secondary Causes: Pitfalls and Prospects. I note also that at the end of his talk, Tkacz acknowledges his indebtedness to Professor William Carroll, who (in his footnotes) highly commends essays written by Professor Alfred Freddoso, defending Suarez's version of concurrentism. I therefore find it puzzling that Professor Tkacz, in his hippopotamus example, makes no attempt to be fair to concurrentists, but instead sets up a "straw man" in an effort to make his "mere conservationism" sound more reasonable to his audience. It would have been much more helpful if he had presented concurrentism in a more balanced manner.

I might add in passing that it is difficult to see how a "mere conservationist" of Professor Tkacz's sort could still call God the Prime Mover. First Cause? Yes, certainly - First Cause of creatures' being. But how could a God who doesn't cause any changes in Nature, but merely maintains it in being, be properly called a Mover at all? (I should add in all fairness that not all "mere conservationists" are as extreme in their views as Professor Tkacz. Some, like the 14th-century medieval philosopher Durandus, regarded God as a remote cause of change, as well as an immediate cause of creatures' being. "Mere conservationists" like Durandus could legitimately call God a Prime Mover.)

*****************************************

Fatal Flaw Number One

Fatal Flaw Number Two

Fatal Flaw Number Three

Fatal Flaw Number Four

Fatal Flaw Number Five

Fatal Flaw Number Four: Tkacz's Assumption That A Competent God Should Be Able To Make A Universe That Can Generate Life In A Predictable Fashion

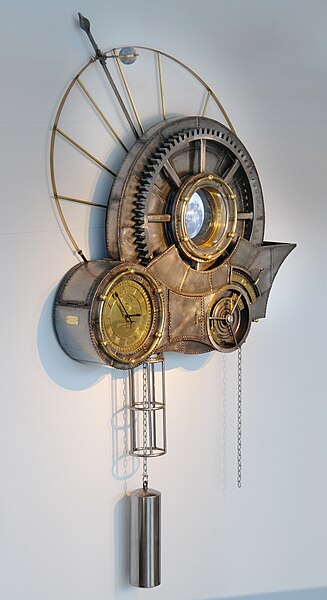

Tim Wetherell's "Clockwork Universe" sculpture, at Questacon, Canberra, Australia. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

The fourth fatal flaw in Professor Tkacz's argument is his un-stated assumption that a truly omnipotent God should be able to make the universe in such a way that it requires no interference in order to bring about whatever appears over the course of time - even bafflingly complex biological structures. In other words, a competent God should be able to make a predictable universe that can reliably generate life in all its diversity. How do I know that's what Professor Tkacz thinks, if he doesn't explicitly say so? Well, here's what he says in the revised version of his talk to the Gonzaga Socratic Club. You be the judge:

Yet, the evidence for God's Creation of the natural universe is the known fact - a fact that we know on the basis of our scientific research - that natural things are intelligible. If they are intelligible, they are so as the products of nature - that is, they are intelligible in terms of their natural causes. If this is true of the totality of natural things, then there must be some ultimate source of this intelligibility - there must be some ultimate cause for the being of any and all natural things....God does not intervene into nature nor does he adjust or "fix up" natural things ... Thus, the evidence of nature's ultimate dependency on God as Creator cannot be the absence of a natural causal explanation for some particular natural structure. Our current science may or may not be able to explain any given feature of living organisms, yet there must exist some explanatory cause in nature.

As I read him, Professor Tkacz is arguing that God should be able to make a universe that can generate life automatically, without God needing to "fix" or "adjust" it. But that assumption may be wrong. Recently, physicist Robert Sheldon has written a thought-provoking article entitled, The Front-Loading Fiction (July 1, 2009), in which he critiques the assumptions underlying "front-loading."

In the first place, the clockwork universe of Laplacean determinism (the idea that you can control the outcomes you get, by controlling the laws and the initial conditions) won't work:

First quantum mechanics, and then chaos-theory has basically destroyed it, since no amount of precision can control the outcome far in the future. (The exponential nature of the precision required to predetermine the outcome exceeds the information storage of the medium.) (Emphases mine - VJT.)

As far as I know, no-one in the "theistic evolution" camp has addressed this bqasic point raised by Dr. Sheldon. Even today, one still commonly hears objections to ID like the following: "Wouldn't it be more elegant of God to design a universe in which the laws of Nature would generate life automatically?" as if that were a genuine possibility.

In the second place, what Dr. Sheldon calls "Turing-determinism" - the modern notion that God could use an algorithm or program to design all the forms we observe in Nature - fares no better:

Turing-determinism is incapable of describing biological evolution, for at least three reasons: Turing's proof of the indeterminancy of feedback; the inability to keep data and code separate as required for Turing-determinancy; and the inexplicable existence of biological fractals within a Turing-determined system.

Specifically, Dr. Sheldon argues that the only kind of universe that could be pre-programmed to produce specific results without fail and without the need for further input would be a very boring, sterile one, without any kind of feedback, real-world contingency or fractals. However, such a universe would necessarily be devoid of any kind of organic life. Dr. Sheldon proposes that God is indeed a "God of the gaps" - an incessantly active "hands-on" Deity Who continually maintains the universe at every possible scale of time and space, in order that it can support life. Such a role, far from diminishing God, actually enhances His Agency.

What I'm suggesting here is that maybe, even God can't make a predictable universe that can generate life in all its diversity. Perhaps the demand that He do so contains a hidden contradiction - and since God cannot do what is logically contradictory, He can hardly be faulted for not being able to make life in the way that Professor Tkacz would like Him to. Like it or not, if we want a universe with life - especially eukaryotic life-forms like us - then we need a manipulating, "hands-on" Deity. And if that strikes some theistic evolutionists as messy, then I can only say to them: get used to it. We live in the real world, and it's God's world, not the world of your Laplacean intellectual fantasies.

*****************************************

Fatal Flaw Number One

Fatal Flaw Number Two

Fatal Flaw Number Three

Fatal Flaw Number Four

Fatal Flaw Number Five

Fatal Flaw Number Five: Professor Tkacz's Assertion That Intelligent Design Is Of Marginal Importance, Even If It Is True

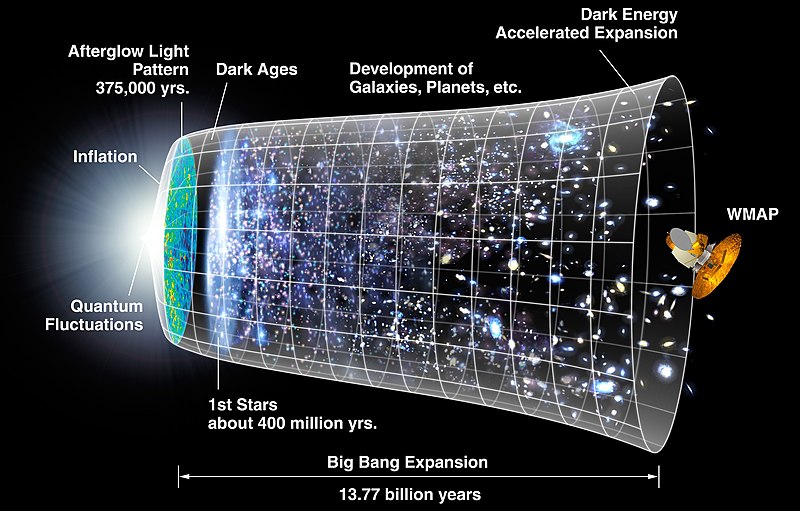

Timeline of the Universe. Courtesy of NASA. Thomists argue that everything in the universe is contingent; hence the universe requires a Necessary Being to explain its existence.

The fifth fatal flaw in Professor Tkacz's case against Intelligent Design is that he accuses ID supporters of being myopically fixated on the unexplained complexity of a mere handful of biological structures in an attempt to prove that God made them, while failing to notice the evidence for God's existence all around them. Tkacz clearly believes that ID proponents can't see the wood for the trees - for on a Thomist view, every contingent being attests to the existence of a wise Creator. As he argues in the revised version of his original speech:

It would seem that ID theory is grounded on the Cosmogonical Fallacy. Many who oppose the standard Darwinian account of biological evolution identify creation with divine intervention into nature. This is why many are so concerned with discontinuities in nature, such as discontinuities in the fossil record. They see in them evidence of divine action in the world, on the grounds that such discontinuities could only be explained by direct divine action...[On a Thomist view], God is the divine reality without which no other reality could exist. Thus, the evidence of nature's ultimate dependency on God as Creator cannot be the absence of a natural causal explanation for some particular natural structure.

Now Professor Tkacz is perfectly right when he asserts that contingent beings point to the existence of a Creator. ID proponents in no way deny this. The value of ID is that it supplements the argument from contingency, which gets us to a Necessary Being, but not an Intelligent Creator.

The beauty of Intelligent Design, in my opinion, is that it complements Aquinas' arguments, by appealing to empirical phenomena which by their very nature can only be produced by an intelligent being. Thus ID provides a via manifestor for modern skeptics, and helps us reason our way towards the existence of an Intelligent Designer of life and the cosmos, because it argues from specific effects which are peculiar to intelligent beings, and which intrinsically require concepts in order to produce them. It also helps us understand better what it means to say that God is intelligent. But I'll have more to say about this in my next post (Part Five of my reply to Professor Tkacz).

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Five

Part One (longer version)