Part One Part Two Part Four Part Five

Part One (longer version)

Until now, we've looked at Aquinas' philosophical and theological views that would have put him at odds with Darwinism. In this section, I shall examine Aquinas' views on the interpretation of Scripture. As we'll see, Aquinas' views on the Bible would have been enough to prevent him from becoming a Darwinist, even if he had had no objections to Darwinism in principle.

This section is divided into four sections:

1. Aquinas on the meaning and interpretation of Scripture

Here, I discuss what Aquinas wrote about the proper way to interpret and understand Scripture. As we shall see, Aquinas' thinking was heavily influenced by that of St. Augustine. Aquinas am historical literalist, but a fairly broad-minded one, whose interpretation of the Bible was completely orthodox, but also highly flexible.

2. Why general exegetical principles are a poor way to assess what Aquinas would have thought of Darwinism

Here, I argue that top-down attempts to deduce what Aquinas would have thought about the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution on the basis of his general exegetical principles are seriously flawed, for three reasons. First, the general exegetical principles identified by scholars in the writings of Aquinas are anything but straightforward in their application. Second, the general principles are extremely sensitive to slight changes in their wording, allowing scholars to arrive at diametrically opposite conclusions about what Aquinas would have thought about evolution. Third, the exegetical principles cited by scholars are incomplete - other principles that were also invoked by Aquinas are seldom mentioned in the scholarly literature.

3. Why Aquinas would have rejected Darwinism as incompatible with Scripture

In this section, I examine Aquinas' exegesis of particular passages in Scripture, and I identify seven convincing arguments showing that if Aquinas were alive today, he would reject Darwinism as being at odds with his whole way of thinking. I maintain that Aquinas' treatment of these concrete Scriptural passages offers a surer guide to how Aquinas interpreted the Bible than any list of general exegetical principles could possibly do.

4. What would Aquinas believe concerning questions relating to origins, if he were alive today?

In the final section, I argue that if Aquinas were alive today, he would most likely be an old-earth creationist, because he seems to have believed in the constancy of Nature. It is possible, but rather doubtful, that Aquinas would accept the scientific evidence for universal common descent; and while he would have no theological objection to an intelligently guided version of evolution that left room for God to produce new kinds of creatures by directly manipulating the genes of existing organisms, he would certainly have no truck with neo-Darwinian evolution. On Scriptural grounds alone, he would have rejected it, for reasons discussed in section 3.

However, accepting an old earth would create exegetical difficulties for Aquinas if he were alive today, because it would force him to acknowledge the vast antiquity of the human race (anywhere from 200,000 years to over two million years, depending on how one chooses to define "human"). This would conflict with his literalistic treatment of the "begats" in Scripture, for if we take the "begats" seriously, then we arrive at an age of only 6,000 years for the human race.

I shall argue that Aquinas would be able to accommodate these difficulties by interpreting the genealogy of Genesis 5 as having a double meaning, in which two sets of ten generations are telescoped into one. The first set is a very ancient one, linking ten individuals who lived two million years ago. Let's call them Adam-1 to Noah-1. The second set of individuals (let's call them Adam-2 to Noah-2) is a much more recent one, dating from around five thousand years ago. The reason why these two sets of ten individuals are linked is that the first set spiritually prefigured the second, from God's perspective. Aquinas' exegetical principles would certainly allow him to interpret Scripture in this fashion, for he taught that even according to the literal sense, a single word in Scripture could have multiple meanings (Summa Theologica I, q. 1 art. 10), if God, the Author of Scripture, intended that it should have those meanings.

This "double meaning" interpretation of Genesis 5 also has implications for the interpretation of Genesis 6-9, as it entails that there were two Noahs, and two Deluges. I propose that the Genesis flood account is actually a telescoping of two floods, separated by a vast interval of time, the first of which prefigured the second. The first flood was a local flood, occurring approximately two million years ago, which wiped out all but eight members of the human race - which was then confined to one small region of Africa - leaving only virtuous Noah-1 and his family. Aquinas' literalistic exegesis of Scripture would force him to insist that must have been a flood must have wiped out the whole human race except for eight individuals, for Scripture clearly states that this happened, as I will demonstrate below.

If the recently proposed "Noah's comet theory" turns out to be correct - for a popular summary, see the article, Did a comet cause the Great Flood? by Scott Carney, in Discover magazine, online edition, November 2007, and for a scholarly summary, see the article, The Archaeology and Anthropology of Quaternary Period Cosmic Impact (N.B. scroll down to page 46) - then the second flood could have been a cataclysmic flood, caused by a cometary impact in 2807 B.C., which led to 180-meter-high mega-tsunamis worldwide, massive flooding from storm surges and extended atmospheric rain-out, and finally, hurricane-force winds, wiping out up to 75% of the human race in one week. Noah-2 would have been one of the survivors, having being prophetically warned by God to build an Ark and stock it with sufficient livestock to provide for himself and his family after the flood. As I will show below, there is a limited but growing body of archaeological evidence to support the "Noah's comet" theory, although it remains highly controversial.

UPDATE: The theory advanced by Dr. Bruce Masse that the Burckle crater, east of Madagascar is the result of a cometary impact in 2807 B.C. has recently been challenged by Dr. Jody Bourgeois, who argues that it is instead the result of aeolian processes. I should add that the crater has not yet been dated by geologists. Finally, Dr. Rob Sheldon has kindly pointed out that a cometary impact would have to be very precise, in order to trigger worldwide coastal flooding of the sort hypothesized by Dr. Masse. As far as I can tell, however, nothing in Aquinas' principles harmonizing faith and science commits him to the proposition that that the second flood was worldwide. It must, however, have included a boat or ark of some sort, since Christ speaks of one.

Thus in the Genesis flood story, we may have an anthropologically universal event (which wiped out all but eight members of the human race), telescoped with a much later worldwide event about 5,000 years ago (which wiped out most but not all of the human race), for literary effect. Thus we have a narrative where the whole earth is filled with violence, and God decides to send a flood to punish humanity. I should add that telescoping was a very common literary technique in the ancient world, and that it was frequently employed by historians. The Christian apologist Glenn Miller has collected an impressive list of examples in his online apologetics article, Contradictions in the Infancy Stories.

While this interpretation of Genesis sounds highly strained to modern ears, Aquinas' understanding of the different levels of meaning in Scripture, which he shared with his medieval contemporaries, would allow him to assimilate it comfortably if he were alive today.

1. Aquinas on the meaning and interpretation of Scripture

A Bible handwritten in Latin, on display in Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire, England. This Bible was copied by hand in Belgium in 1407 A.D., and was used for reading aloud in a monastery.

(a) What Aquinas wrote about the meaning of Scripture

Aquinas wrote many commentaries on the books in Scripture, but he left behind no treatise on the interpretation of Scripture. In order to reconstruct Aquinas' thought, we therefore have to rely on what we can glean from various passages in his writings.

I would recommend the following online articles as helpful for readers wanting to know more about how Aquinas understood the meaning of Scripture:

St. Thomas Aquinas and Sacred Scripture by John F. Boyle, Department of Theology, University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Aquinas, the Literal Sense of Scripture and Theology by Professor Michael Barber, John Paul the Great Catholic University, San Diego, California.

Aquinas' Biblical commentaries can be found here.

Aquinas set forth his views on the meaning of Scripture in his Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10. Aquinas' teachings on the meaning of Scripture may be conveniently summarized under the following eight points.

KEY POINT # 1: The author of Scripture is God.

The key point is that for St. Thomas, the author of Scripture is God. Hence, each word in Scripture means what God intends it to mean, and sometimes the same word can have multiple meanings. God's intellect is able to encompass these various meanings, because it understands everything. As St. Thomas puts it:

I answer that, The author of Holy Writ is God, in whose power it is to signify His meaning, not by words only (as man also can do), but also by things themselves... Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 1.)

KEY POINT # 2: Words used in Scripture may have both a literal sense and a spiritual sense.

According to St. Thomas, words used in Scripture may have both a literal sense and a spiritual sense. The literal or historical sense of a word in Scripture refers to the thing it directly signifies. If this thing also signifies another thing, then that thing may be described as the spiritual sense of the word. The distinction between the literal and spiritual meanings of Scripture is a vital one, as Fr. Joseph Boyle explains in his essay, St. Thomas Aquinas and Sacred Scripture:

The spiritual sense is carefully distinguished from the literal. If the literal sense is concerned with what things the words signify, the spiritual sense is concerned with what those things, signified by the words, in turn signify.

In the words of St. Thomas:

I answer that, The author of Holy Writ is God, in whose power it is to signify His meaning, not by words only (as man also can do), but also by things themselves. So, whereas in every other science things are signified by words, this science has the property, that the things signified by the words have themselves also a signification. Therefore that first signification whereby words signify things belongs to the first sense, the historical or literal. That signification whereby things signified by words have themselves also a signification is called the spiritual sense, which is based on the literal, and presupposes it. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 1.)

KEY POINT # 3: The literal meaning of Scripture is always primary: the spiritual sense presupposes the literal and is built upon it.

That signification whereby things signified by words have themselves also a signification is called the spiritual sense, which is based on the literal, and presupposes it. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 1.)

And again:

Reply to Objection 1. The multiplicity of these senses does not produce equivocation ... because the things signified by the words can be themselves types of other things. Thus in Holy Writ no confusion results, for all the senses are founded on one - the literal - from which alone can any argument be drawn, and not from those intended in allegory, as Augustine says (Epis. 48). (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 1.)

KEY POINT # 4: The literal meaning of Scripture is sufficient: it contains everything in Scripture that we need to believe.

Reply to Objection 1. ... Nevertheless, nothing of Holy Scripture perishes on account of this, since nothing necessary to faith is contained under the spiritual sense which is not elsewhere put forward by the Scripture in its literal sense. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 1.)

KEY POINT # 5: The spiritual sense of Scripture is threefold.

The spiritual sense of Scripture may be (1) allegorical (signifying Christ Himself in some way), (2) moral (signifying how Christians are to live), or (3) anagogical (signifying Heaven, our eternal destination, for which God created us). As Fr. Boyle explains it in his essay, St. Thomas Aquinas and Sacred Scripture:

Thomas divides the spiritual sense into three senses: allegorical, moral, and anagogical. Each is related to Christ. The allegorical sense is the signification of Christ Himself, especially in the Old Testament (such as the paschal lamb above). This does not necessarily include prophecy of Christ; such passages might well be literal significations of Christ. To be truly allegorical in the precise way in which Thomas means it here requires that the words signify some thing and that that thing in turn signifies Christ.The second sense is the moral in which something signifies how Christians are to act. For Thomas, first and foremost it is the actions of Christ himself and then of the saints (as exemplary members of His body) that signify the actions proper to the Christian life...

Finally, in the third sense, the anagogical, what is signified is the beatific life of heaven with Christ. For example, the observance of the sabbath not only keeps the creation of the world always before one's eyes (here Thomas cites Moses Maimonides for the literal sense), but it also signifies the eternal rest that the saints enjoy in glory.

KEY POINT # 6: The literal sense of Scripture is threefold.

For St. Thomas, the literal sense is very broad. It includes: (1) any narrative of an historical event (history); (2) the explanation of why an historical event narrated in the Bible happened (etiology); and (3) an analogy drawn between two different historical events narrated in Scripture.

Reply to Objection 2. These three ó history, etiology, analogy ó are grouped under the literal sense. For it is called history, as Augustine expounds (Epis. 48), whenever anything is simply related; it is called etiology when its cause is assigned, as when Our Lord gave the reason why Moses allowed the putting away of wives ó namely, on account of the hardness of men's hearts; it is called analogy whenever the truth of one text of Scripture is shown not to contradict the truth of another. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 2.)

KEY POINT # 7: In Scripture, even metaphorical language is part of the literal sense.

Even metaphorical language is also literal, according to St. Thomas:

Reply to Objection 3. The parabolical sense is contained in the literal, for by words things are signified properly and figuratively. Nor is the figure itself, but that which is figured, the literal sense. When Scripture speaks of God's arm, the literal sense is not that God has such a member, but only what is signified by this member, namely operative power. Hence it is plain that nothing false can ever underlie the literal sense of Holy Writ. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10, reply to objection 3.)

KEY POINT # 8: The literal meaning of a word in Scripture could be multiple.

Finally, and most importantly for the exegetical discussion in Section 4 below, the literal meaning of a word in Scripture could be multiple, according to Aquinas. This is perfectly appropriate, since the author of Scripture is God, who is perfectly capable of understanding many things at once, and hence of intending to signify a multitude of different things by one word:

Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses. (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10.)

(b) Key texts by St. Thomas Aquinas, on the proper interpretation of Scripture

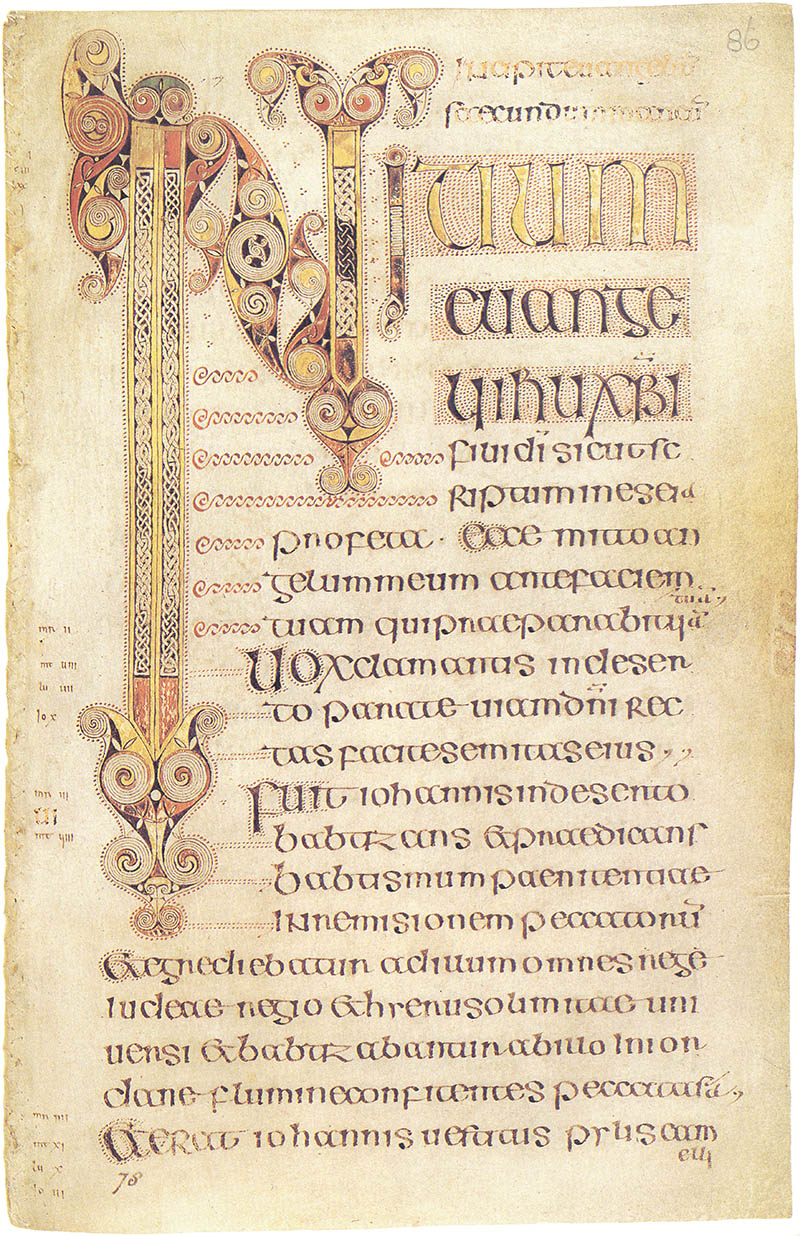

The beginning of the Gospel of Mark. Image of page from the 7th century Book of Durrow. Trinity College, Dublin.

Although Aquinas wrote no exegetical treatises, the following passages in his writings give us some valuable clues to his thinking, regarding the proper interpretation of Scripture.

(i) Aquinas on the firmament created by God on the second day of Genesis 1

In his Summa Theologica I, q. 68, art. 1, St. Thomas addresses the question of what Scripture means when it says that God made a "firmament" on the second day. St. Thomas was well aware that philosophers had different opinions about this "firmament," and he did not wish to tie himself to any particular interpretation, as it might well turn out to be wrong. To help him resolve this difficulty, he cites two exegetical guidelines that were originally formulated by St. Augustine in his De Genesi ad litteram:

In discussing questions of this kind two rules are to observed, as Augustine teaches (Gen. ad lit. i, 18). The first is, to hold the truth of Scripture without wavering. The second is that since Holy Scripture can be explained in a multiplicity of senses, one should adhere to a particular explanation, only in such measure as to be ready to abandon it, if it be proved with certainty to be false; lest Holy Scripture be exposed to the ridicule of unbelievers, and obstacles be placed to their believing. (Italics and emphases mine - VJT.)

Later on, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 68, art. 2, Aquinas confronts the thorny question of what Genesis 1 means when it narrates that God created the waters above the firmament, on the second day. In this article, Aquinas once again begins by citing the authority of St. Augustine. Aquinas' wording in the passage below demonstrates that he had the highest regard for the authority of Scripture, even when he did not fully understand it:

I answer with Augustine (Gen. ad lit. ii, 5) that, "These words of Scripture have more authority than the most exalted human intellect. Hence, whatever these waters are, and whatever their mode of existence, we cannot for a moment doubt that they are there."

The reader should note what St. Thomas is doing here. He does not allegorize the passage away, by giving it a purely spiritual interpretation; rather, he insists that it has a literal meaning, even if we haven't discerned the correct one yet.

Even while insisting that the firmament had a literal meaning, Aquinas firmly rejected any interpretation of Scripture that "can be shown to be false by solid reasons." Thus in his Summa Theologica I, q. 68, article 3, Aquinas writes:

... The text of Genesis, considered superficially, might lead to the adoption of a theory similar to that held by certain philosophers of antiquity, who taught that water was a body infinite in dimension, and the primary element of all bodies...As, however, this theory can be shown to be false by solid reasons, it cannot be held to be the sense of Holy Scripture.

(ii) Aquinas on the meaning of the days of creation in Genesis 1

Another oft-cited passage can be found in Aquinas' Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, q. 1, art. 2, where Aquinas addresses the question of whether things of all kinds were created simultaneously, distinct in their species, at the beginning of time, as St. Augustine had held, or whether they were made over a period of six 24-hour days, as the other Christian Fathers maintained:

It should be said that what pertains to faith is distinguished in two ways, for some are as such of the substance of faith, such that God is three and one, and the like, about which no one may licitly think otherwise. Hence the Apostle in Galatians 1:8, 'But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel to you other than that which we have preached to you, let him be anathema!' Other things are only incidental to faith insofar as they are treated in Scripture, which faith holds to be promulgated under the dictation of the Holy Spirit, but which can be ignored by those who are not held to know scripture, such as many of the historical works. On such matters even the saints disagree, explaining scripture in different ways. Thus with respect to the beginning of the world something pertains to the substance of faith, namely that the world began to be by creation, and all the saints agree in this.But how and in what order this was done pertains to faith only incidentally insofar as it is treated in scripture, the truth of which the saints save in the different explanations they offer. For Augustine holds that ... [w]ith respect to the distinction of things we ought to attend to the order of nature and doctrine, not to the order of time.

As to nature, just as sound precedes song in nature, though not in time, so things which are naturally prior are mentioned first, as earth before animals, and water before fish, and so with other things. But in the order of teaching, as is evident in those teaching geometry, although the parts of the figure make up the figure without any order of time, still the geometer teaches the constitution as coming to be by the extension of line from line. And this was the example of Plato, as we are told at the beginning of On the Heavens. So too Moses, instructing an uncultivated people on the creation of the world, divides into parts what was done simultaneously.

Ambrose, however, and other saints hold the order of time is saved in the distinction of things. This is the more common opinion and superficially seems more consonant with the text, but the first is more reasonable and better protects Sacred Scripture from the derision of infidels, which Augustine teaches in his literal interpretation of Genesis is especially to be considered, and so scripture must be explained in such a way that the infidel cannot mock, and this opinion is more pleasing to me. However, the arguments sustaining both will be responded to.

The Scriptural passages above are often cited by Aquinas scholars. However, there are other passages in Aquinas' writings, which are less often cited in the scholarly literature, in which Aquinas makes clear his preference for the plain meaning of Scripture.

(iii) Aquinas on the literal existence of the Paradise (Garden of Eden) described in Genesis 2

For instance, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 102, art. 1, Aquinas discusses the question of whether Paradise was a literal place or a figurative, spiritual place, and concludes that it was both:

I answer that, As Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xiii, 21): "Nothing prevents us from holding, within proper limits, a spiritual paradise; so long as we believe in the truth of the events narrated as having there occurred." For whatever Scripture tells us about paradise is set down as a matter of history; and wherever Scripture makes use of this method, we must hold to the historical truth of the narrative as a foundation of whatever spiritual explanation we may offer.

(iv) Aquinas on the literal meaning of the "begats" in Scripture

In another passage which is rarely cited in the scholarly literature (Summa Theologica I, q. 32, art. 4), Aquinas discusses the ways in which a doctrine - even a trivial one, like the fact that Samuel was the son of Elcana - can be a matter of faith:

Anything is of faith in two ways; directly, where any truth comes to us principally as divinely taught, as the trinity and unity of God, the Incarnation of the Son, and the like; and concerning these truths a false opinion of itself involves heresy, especially if it be held obstinately. A thing is of faith, indirectly, if the denial of it involves as a consequence something against faith; as for instance if anyone said that Samuel was not the son of Elcana, for it follows that the divine Scripture would be false. Concerning such things anyone may have a false opinion without danger of heresy, before the matter has been considered or settled as involving consequences against faith, and particularly if no obstinacy be shown; whereas when it is manifest, and especially if the Church has decided that consequences follow against faith, then the error cannot be free from heresy.

(v) Aquinas on the literal existence of Job, as an historical individual

Finally, in the Prologue of Aquinas' Commentary on Job) Aquinas considers and rejects the view that the book of Job is intended as nothing more than a parable. The Jewish philosopher and Rabbi Moses Maimonides (1135-1204), following other Jewish sages, had asserted in his Guide for the Perplexed, Part III, chapter 22, that the book was not factual, but a work of fiction, designed to teach us about Providence. Maimonides based his denial of the historicity of Job on the total absence of biographical information in the book concerning Job's ancestry, his parents and when he lived. All we are told about Job is that "In the land of Uz there lived a man whose name was Job" (Job 1:1, New International Version). Nevertheless, St. Thomas is quite emphatic that Job is a real historical character:

But there were some who held that Job was not someone who was in the nature of things [i.e. not a real, historical person - VJT.], but that this was a parable made up to serve as a kind of theme to dispute providence, as men frequently invent cases to serve as a model for debate. Although it does not matter much for the intention of the book whether or not such is the case, still it makes a difference for the truth itself. This aforementioned opinion seems to contradict the authority of Scripture. In Ezechiel, the Lord is represented as saying, "If there were three just men in our midst, Noah, Daniel, and Job, these would free your souls by their justice." (Ez. 14:14) Clearly Noah and Daniel really were men in the nature of things and so there should be no doubt about Job who is the third man numbered with them. Also, James says, "Behold, we bless those who persevered. You have heard of the suffering of Job and you have seen the intention of the Lord." (James 5:11) Therefore one must believe that the man Job was a man in the nature of things.

These are the key texts on the interpretation of scripture which I have managed to locate in the writings of Aquinas. I shall return to these passages in Sections 2 and 3.

2. Why general exegetical principles are a poor way to assess what Aquinas would have thought of Darwinism

Philippe de Champaigne, "Saint Augustine," 1645-1650. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

St. Augustine's views on the interpretation of Scripture had a profound influence on St. Thomas Aquinas.

Various scholars have adopted a "top-down" approach when discussing how theologians such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas interpreted Scripture. The aim here is to identify the general exegetical principles which they make use of in their writings, in order to deduce how they would have approached concrete scientific issues, such as the Copernican claim that the Earth goes around the sun, or Darwin's theory of evolution.

I have consciously rejected this approach, when addressing the question of whether Aquinas' reading of Scripture would have prevented him from accepting Darwin's theory of evolution. My reasons for doing this are as follows:

(i) the general exegetical principles identified by scholars in the writings of St. Augustine and other theologians are anything but straightforward in their application;

(ii) the general principles are extremely sensitive to slight changes in their wording, allowing scholars to arrive at diametrically opposite conclusions about how a theologian like Augustine or Aquinas would have addressed this or that issue; and

(iii) the exegetical principles cited by scholars are incomplete - other principles that were used by these theologians are seldom mentioned in the scholarly literature.

In recent years, the excellent work of Professor Ernan McMullin has often been cited by scholars, in particular his essay, "Galileo on Science and Scripture," in The Cambridge Companion to Galileo, ed. Peter Machamer (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 271-347. An incomplete online copy of his essay can be viewed here. For a succinct summary of Professor McMullin's principles, I would recommend Professor Craig Boyd's article, Using Galileo: A Developmental and Historical Approach. I would also strongly recommend the following article by Dr. Gregory Dawes, entitled, Could there be another Galileo case? Galileo, Augustine and Vatican II.

McMullin identifies five principles for interpreting Scripture in the writings of St. Augustine. I shall examine the first three together:

(a) The Priority of Prudence, the Priority of demonstration and the Priority of Scripture

1. Principle of the Priority of Prudence:

When trying to discern the meaning of a difficult Scripture passage, one should keep in mind that different interpretations of the text may be possible, and that, in consequence one should not rush into premature commitment to one of these, especially since further progress in the search for truth may later undermine this interpretation.

2. Principle of Priority of Demonstration:

When there is a conflict between a proven truth about nature and a particular reading of Scripture, an alternative reading of Scripture must be sought.

3. Principle of Priority of Scripture:

When there is an apparent conflict between a Scripture passage and an assertion about the natural world grounded on sense or reason, the literal reading of Scripture should prevail as long as the latter assertion lacks demonstration.

The key problem with these three principles is an epistemological one, which should be immediately apparent to an attentive reader: what counts as a demonstration? In other words, what criteria do we use to rule out an interpretation of Scripture as demonstrably wrong? By themselves, the principles are unable to resolve this question.

Professor McMullin has devoted considerable thought to this matter. His response as follows:

I am using the term "demonstration" here in the broad sense to mean any form of convincing proof and not just deductive proof from principles grasped as true in their own right (the technical Aristotelian sense of the term, to which Augustine does not confine himself). Augustine's emphasis is on the certainty that is needed for the claim to natural knowledge to count as a challenge to a Scripture reading. He uses phrases in this context like "the facts of experience," "knowledge acquired by unassailable arguments or proved by the evidence of experience," and "proofs that cannot be denied" (above). (Op. cit., p. 294.)

The problem with this view for evolutionists is that the case for the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution is not demonstrative in the sense intended by St. Augustine. It does not rest on "proofs that cannot be denied," "unassailable arguments" or "the facts of experience." Experience tells us only that species can evolve. But there is no direct evidence from scientific observations that microbe-to-man evolution is possible, as a result of purely natural processes.

"Portrait of Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban," by John Vanderbank, 1731(?), after a portrait by an unknown artist (circa 1618). National Portrait Gallery, London.

Francis Bacon, father of the modern scientific method, employed an inductive notion of demonstration. That of Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas and Galileo was deductive, however.

An additional problem, highlighted by Professor Boyd, is that the modern scientific method employs a notion of demonstration that is strikingly different from that of Galileo (and before him, St. Augustine). So far we have examined two contrasting notions of a demonstration:

(i) a "pure" mathematical notion, based on self-evident principles (i.e. Aristotle's narrow notion of a demonstration);

(ii) an empirical notion, based on "the facts of experience" (a notion which was also appealed to by Augustine).

Combining these two, we may add a third notion:

(iii) a deductive demonstration which employs reasoning, based on certain facts which are confirmed by experience - in other words, the kind of demonstration that Sherlock Holmes might use when solving a murder case. The phrase, "knowledge acquired by unassailable arguments or proved by the evidence of experience," cited by McMullin, could include this third type of demonstration as well.

What all these notions have in common, however, is that they are either immediately evident or deductions from what is immediately evident. Writing in the early seventeenth century, Galileo likewise envisaged demonstration as proceeding deductively. In this respect, he did not depart from Aristotle's thinking. Galileo's major modification of the Aristotelian idea of a demonstration was that it should proceed on the basis of sensory observation, instead of Aristotle's fixed essences. However, modern science proceeds inductively, as Professor Craig Boyd points out in the article I cited above:

The assumption Galileo makes here is that demonstration itself can "prove" the truth of his own perspective along the lines of a modified Aristotelian notion of demonstration wherein a major premise followed by a minor premise produced a conclusion, in a deductive manner. For Galileo "demonstration" included this idea but instead of appealing to Aristotelian essences in the reasoning process, he employed mathematics and sensory observation. Today we no longer accept this view of demonstration and therefore Galileo's commitment to this method would ultimately undermine his own arguments since on this view neither truth nor "demonstration" are possible since "scientific method" proceeds inductively. (Op. cit., p. 285.)

If Galileo couldn't even prove his own theory in a purely deductive manner, on the basis of sensory observations, how much less would a neo-Darwinian evolutionist be able to prove the theory of evolution in such a fashion, since the theory is forced to posit unobservable and non-replicable events, such as the origin of life and the diversification of the various phyla of animals (the "Cambrian explosion")?

How Aquinas have regarded the epistemic status of the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution? Would he regarded the modern scientific case for evolution as a demonstration? As we saw from "Smoking Gun" number 7, Corollary 2 (in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz), Aquinas would have answered this question firmly in the negative. The key events that are alleged to have occurred cannot be replicated, and they do not take place in a regular, repeatable fashion. There is no proof that microbe-to-man evolution could possibly work. The existence of a few fossils linking fish to amphibia, or reptiles to mammals, might suggest common ancestry, but they fail to establish a naturalistic mechanism. That is the key issue here: the proposition that the origin and diversity of life can be accounted for in purely naturalistic terms.

Let us now examine Professor McMullin's remaining two exegetical principles, which he claims to have identified in the writings of St. Augustine.

(b) The Principle of Accommodation

Professor McMullin's fourth exegetical principle is a very common-sensical one.

4. Principle of Accommodation:

The choice of language in the Scripture is accommodated to the capacities of the intended audience.

This exegetical principle of Augustine's is a non-controversial one, and it was also invoked by St. Thomas Aquinas. When citing St. John Chrysostom's explanation of why the creation of the angels is not mentioned in the book of Genesis, Aquinas writes:

Moses was addressing an ignorant people, to whom material things alone appealed, and whom he was endeavoring to withdraw from the service of idols" (Summa Theologica, Vol. I, q. 67, article 4).

St. Thomas makes use of the same principle when explaining why the Creation account in Genesis 1 makes mention of God creating the land and sea, but not the atmosphere:

It should rather be considered that Moses was speaking to ignorant people, and that out of condescension to their weakness he put before them only such things as are apparent to sense. Now even the most uneducated can perceive by their senses that earth and water are corporeal, whereas it is not evident to all that air also is corporeal, for there have even been philosophers who said that air is nothing, and called a space filled with air a vacuum.Moses, then, while he expressly mentions water and earth, makes no express mention of air by name, to avoid setting before ignorant persons something beyond their knowledge" (Summa Theologica I, q. 68, article 3).

The reader should note, however, that St. Thomas was careful not to attribute any erroneous beliefs to the human author of Genesis, whom he believed to have been Moses. It was Moses' audience who were ignorant, and not Moses himself.

(c) The Principle of Limitation

It now remains to discuss Professor McMullin's fifth and final and most controversial exegetical principle:

5. Principle of Limitation:

Since the primary concern of Scripture is with human salvation, texts of Scripture should not be taken to have a bearing on technical issues of natural science.

The key problem with this principle is that it is highly doubtful that St. Augustine himself ever advocated it, and there is no evidence that Aquinas did.

Why Galileo ascribed the Principle of Limitation to St. Augustine, and how Galileo went beyond it

Galileo Galilei. Portrait by Leoni.

Professor Ernan McMullin has claimed that St. Augustine endorsed the Principle of Limitation in his writings, citing a passage in chapter nine of book two of Augustine's De Genesi ad Litteram (On the Literal Meaning of Genesis), where he addresses the question of "the form and shape of heaven according to Sacred Scripture." In this passage, Augustine states that while "in the matter of the shape of heaven the sacred writers knew the truth, . . . the Spirit of God, who spoke through them, did not wish to teach men these facts that would be of no avail for their salvation" (1982: 2.9.20).

The astronomer Galileo certainly believed that St. Augustine was advocating the Principle of Limitation in his De Genesi ad Litteram, and he cited the same passage from St. Augustine in support of his own position, that the Bible is meant to tell us how to go to Heaven, and not how the heavens go. Of course, Galileo had a strong theological motive for doing so, as various passage in Scripture seemed to contradict his assertion that the Earth went round the Sun - for instance, Joshua 10:12-13, in which the sun is said to cease its movement in response to Joshua's prayers.

However, Galileo himself advocated a position that went beyond the Principle of Limitation, as Dr. Gregory Dawes has pointed out in an article entitled Could there be another Galileo case? Galileo, Augustine and Vatican II. Galileo's own position, which he articulated in a letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of Lorraine, was very similar to the "non-overlapping magisteria" principle (NOMA) espoused by the late Stephen Jay Gould. As Dr. Dawes puts it:

He not only argues that the purpose of Scripture is different from that of the natural sciences; he draws the conclusion that the authority of the Bible is effectively limited to matters with which the natural sciences cannot deal.

In other words, Galileo seems to have espoused a principle which another commentator, Marcello Pera, has referred to as a "principle of independence," which states that "science and religion belong to, and are competent on, two distinct and different domains."

The Principle of Limitation: what St. Augustine really thought

However, Dr. Dawes contends that Professor McMullin's (and Galileo's) attribution of the Principle of Limitation to St. Augustine is highly questionable, and cites as evidence St. Augustine's remarks (De Genesi ad litteram 2.16.33-34) on the question of whether the sun, the moon and the stars are actually of equal brightness. Even in St. Augustine's day, long before the invention of the telescope, there were some people who were suggesting that the stars were actually just as bright as the sun, and that they appeared fainter only because of their greater distance from the earth. In his initial response, St. Augustine tells his readers that believers should avoid "subtle enquiries" (subtilius aliquid quaerere), adding that "for us it would seem sufficient to recognize that, whatever may be the true account of all this, God is the Creator of the heavenly bodies." But then he immediately adds: "And yet we must hold to the pronouncement of St. Paul, There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another of the stars; for star differs from star in glory [1 Cor 15:41]." Dr. Dawes comments:

In other words, whatever position one accepts, Augustine insists it must be compatible with 1 Corinthians. If he truly held to a principle of limitation, he would not have regarded 1 Corinthians 15:41 as having a bearing on this matter at all.

The intrinsic brightness of the stars is a technical scientific matter, and yet St. Augustine clearly believed that a passage in Scripture could have a bearing on the issue. It would seem, then that Professor Ernan McMullin's interpretation of St. Augustine is mistaken. Dr. Dawes contends that Augustine actually endorsed a different principle, which he calls the "Principle of Differing Purpose":

What I want to argue is that neither position - neither a principle of limitation nor a principle of independence - can plausibly be attributed to Augustine. It is worth noting that McMullin himself seems uneasy with doing so. He does so only with the concession that Galileo holds to a much broader form of that principle than Augustine would have accepted. Augustine holds only that Biblical authority should not be invoked when it comes to "technical issues of natural science" (emphasis mine), while Galileo suggests it should not be invoked with regard to any kind of natural knowledge (1998: 306). But this is a slippery distinction. At what point, for instance, does a knowledge of nature in general, where Augustine does invoke the authority of Scripture, fade over into "technical issues of natural science," where apparently he would not? In any case, a close examination of De Genesi ad litteram suggests that Augustine's position is not accurately described as a "principle of limitation," in any sense of those words. Unlike Galileo, Augustine is not interested in limiting the authority of the biblical writings. He therefore holds to an entirely different principle, with a rather different set of implications. Augustine's hermeneutical principle in the matter of what we would call science and religion is better described as a "principle of differing purpose."

Dr. Dawes continues:

The purpose of 1 Corinthians 15 is not to teach the physical details of the universe, but to speak about human bodies at the resurrection of the dead, a fact which Augustine recognizes in the same passage ("Paul speaks thus because of the likeness of the stars to risen bodies of men"). Compared to the doctrine of the resurrection, such subtle speculations about the structure of the universe are rather a waste of valuable time (cf. 1982: 2.16.34). Yet - and this is the key point - when, in fulfilling this more serious purpose, the Scriptures make reference to aspects of the physical world, what they say must be taken with the utmost seriousness.<9> Pace McMullin, such biblical texts do "have a bearing on technical issues of natural science," even if they were not written for that purpose. As it turns out, Augustine suggests that 1 Corinthians 15:41 could be interpreted in such a way that it does not preclude the scientific opinion he is discussing. One could, for instance, argue that, while the heavenly bodies are all of the same brightness in themselves, St. Paul's remark refers to their differing degrees of brightness when seen by us. But at the end of the day, Augustine suggests that believers should accept the plain meaning of Genesis 1:16, even in this rather technical matter. As he writes, "we do better when we believe that those two luminaries [the sun and the moon] are greater than the others, since Holy Scripture says of them, And God made the two great lights" (1982: 2.16.34).

Obviously, St. Augustine was wrong in his astronomy. However, his reasoning concerning the Scriptural passages cited above certainly indicates that he did not hold to the Principle of Limitation which Professor McMullin ascribes to him.

Did Aquinas endorse the Principle of Limitation?

What about St. Thomas Aquinas? Did he endorse Professor McMullin's Principle of Limitation? Various authors have claimed to identify the Principle of Limitation in his writings, and the following passage in Aquinas' Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, article 2 is often cited in this regard. Here, St. Thomas is addressing the question: "Are All Things Created Simultaneously, Distinct In Their Species?"

It should be said that what pertains to faith is distinguished in two ways, for some are as such of the substance of faith, such that God is three and one, and the like, about which no one may licitly think otherwise. Hence the Apostle in Galatians 1:8, "But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel to you other than that which we have preached to you, let him be anathema!" Other things are only incidental to faith insofar as they are treated in Scripture, which faith holds to be promulgated under the dictation of the Holy Spirit, but which can be ignored by those who are not held to know scripture, such as many of the historical works. On such matters even the saints disagree, explaining scripture in different ways. Thus with respect to the beginning of the world something pertains to the substance of faith, namely that the world began to be by creation, and all the saints agree in this.But how and in what order this was done pertains to faith only incidentally insofar as it is treated in scripture, the truth of which the saints save in the different explanations they offer.

A superficial reading of this passage might lead one to think that for Aquinas, the mere fact that the world came into existence by creation was the only point in the account of Genesis 1 that was set in stone, while everything else in the account remained open to differing interpretations. Indeed, this is precisely the interpretation placed on this passage by Professor William E. Carroll, Thomas Aquinas Fellow in Science and Religion at Blackfriars Hall and a member of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Oxford. Professor Carroll has written an article entitled Creation, Evolution and Thomas Aquinas, in which he argues that Aquinas would have had no problems with neo-Darwinian evolution, as a scientific theory:

Some defenders as well as critics of evolution, as we shall see later, think that belief in the Genesis account of creation is incompatible with evolutionary biology. Aquinas, however, did not think that the Book of Genesis presented any difficulties for the natural sciences, for the Bible is not a textbook in the sciences. What is essential to Christian faith, according to Aquinas is the "fact of creation," not the manner or mode of the formation of the world...

Nevertheless, a word of caution is in order here. Let us begin with the question addressed by Aquinas: "Are All Things Created Simultaneously, Distinct In Their Species?" The very wording of the question makes it clear that St. Augustine's theory of simultaneous creation (which is being considered here) is not an evolutionary one. There were two schools of thought on this question: most of the Christian Fathers were of the view that creatures were made over a period of six days, while St. Augustine of Hippo believed that they were created simultaneously. (Aquinas was inclined to favor the Augustinian view.) What both schools took for granted, however, was that each and every kind (or species) of creature was made separately by God. Aquinas taught this too, as we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 8, section (e), in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz. In fact, no Christian theologian questioned the view that each and every kind of creature was made separately by God, until the 19th century.

While Aquinas insists on the fact of creation as being something essential to faith, he also writes that "how and in what order this was done pertains to faith only incidentally." It would be fair to conclude from this that the sequence and mode of God's creative acts is not part of the Christian faith, according to Aquinas.

However, the question of how and in what order God created are quite distinct from the question of what God created. On this point, Aquinas is quite clear: God created "all things ... distinct in their species," as the header of the article cited above puts it (Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, article 2). Neither side denied this. The question on which they differed was the timing: did it happen all at once, or over a period of six 24-hour days?

Even though Aquinas noted in the passage above that "many of the historical works" can be explained in different ways because of the diversity of opinions regarding the interpretation of these works, they still remained historical for Aquinas. As we have already noted, that St. Thomas believed that the literal, historical sense of Scripture was of primary importance: "all the senses are founded on one - the literal - from which alone can any argument be drawn, and not from those intended in allegory, as Augustine says (Epis. 48)" (Summa Theologica I, q. 1, art. 10).

Aquinas also insisted that Christians were bound to accept the literal interpretation of Scripture any events in the Bible that were "set down as matter of history." Thus when discussing the question of whether the word "Paradise" in Genesis 2 referred to an actual, historical place or a figurative, spiritual one, he writes:

I answer that, As Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xiii, 21): "Nothing prevents us from holding, within proper limits, a spiritual paradise; so long as we believe in the truth of the events narrated as having there occurred." For whatever Scripture tells us about paradise is set down as a matter of history; and wherever Scripture makes use of this method, we must hold to the historical truth of the narrative as a foundation of whatever spiritual explanation we may offer (Summa Theologica I, q. 102, art. 1).

We can see just how much of a literalist St. Thomas was from the following passage in his Summa Theologica I, q. 32, article 4, where he is discussing a speculative theological question regarding the Trinity. St. Thomas asserts that truths that are part of the Christian faith fall into two categories: Divinely revealed truths which are received directly from God, and truths which are not directly received from God, but which cannot be denied without contradicting some Divinely revealed truth. Denial of divinely revealed truths is simply heretical:

Anything is of faith in two ways; directly, where any truth comes to us principally as divinely taught, as the trinity and unity of God, the Incarnation of the Son, and the like; and concerning these truths a false opinion of itself involves heresy, especially if it be held obstinately. A thing is of faith, indirectly, if the denial of it involves as a consequence something against faith; as for instance if anyone said that Samuel was not the son of Elcana, for it follows that the divine Scripture would be false.

St. Thomas' logic is quite straightforward: denying that Samuel was the son of Elcana entails that Scripture is false, which is contrary to the faith; hence the proposition that Samuel was the son of Elcana is indirectly a matter of faith. However, Christians were free to have different opinions on questions where it has not been established that anything contrary to the faith would follow. That includes abstruse, speculative questions relating to the Trinity, such as the number of properties distinguishing the three Divine Persons. (These distinguishing properties were technically known as nodes in Aquinas' day.) "Concerning such things," Aquinas writes, "anyone may have a false opinion without danger of heresy, before the matter has been considered or settled as involving consequences against faith."

We have seen that any attempt to deduce Aquinas' position on evolution purely on the basis of his general exegetical principles is fraught with peril. In the following section, I shall put forward several arguments attempting to show why Aquinas would have rejected Darwinism, based on his exegesis of particular passages in Scripture. These passages, I believe, offer a surer guide to Aquinas' thinking, as they are based on specific cases. As such, they supply us with a clearer picture of the logic underlying Aquinas' thinking, both as a medieval theologian and as a philosopher.

3. Why Aquinas would have rejected Darwinism as incompatible with Scripture

If we focus on Aquinas' remarks concerning particular passages in Scripture, we can identify at least seven reasons why he would have rejected Darwinism, on Scriptural grounds alone.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, "St. Jerome in his study," 1480. Church of Ognissanti, Florence.

Aquinas shared St. Jerome's opinion that the world was less than 6,000 years old.

First, Aquinas evidently shared the opinion of St. Jerome, a Doctor of the Church who translated the Bible into Latin, that the world was less than 6,000 years old, even if he disagreed with St. Jerome's opinion that the angels were created long before the corporeal world. Aquinas argued that angels were created along with the world, rather than in some distant age before the world as St. Jerome held; however, he did not question St. Jerome's chronology for the cosmos. Thus for Aquinas, the angels were less than 6,000 years old, too. Readers can verify this for themselves: it is in Aquinas' Summa Theologica I, q. 61, article 3, objection 1. But there's more. St. Augustine, whose writings Aquinas constantly cited, explicitly taught that the human race was created less than 6,000 years ago. In his City of God, Book XII, chapter 12, St. Augustine wrote that "according to Scripture, less than 6000 years have elapsed since He [man] began to be." In fact, the Fathers of the Church were absolutely unanimous on this point. "What about Origen?" I hear some of you ask. "Didn't he champion an allegorical interpretation of Scripture?" Yes, he did, but even Origen vigorously defended "the Mosaic account of the creation, which teaches that the world is not yet ten thousand years old, but very much under that," against the pagan skeptic, Celsus, in his book, Contra Celsus (Against Celsus) Book 1, chapter 19.

Second, instead of interpreting the days of Genesis 1 as long ages, as some Christians began to do in the nineteenth century, Aquinas favored the opinion of St. Augustine, that the six days of Genesis were really a single instant. In his Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, article 2, he notes the common view of the Church Fathers that the six days were sequential 24-hour days, but endorses St. Augustine's view that the work of the six days was accomplished in a single instant and subsequently revealed in stages to the angels, as they, with their finite minds, were incapable of taking it all in at once. St. Augustine thought that this view protected the Christian faith from the ridicule of unbelievers, who asked why it took God a whole week to make the world.

It is vital for the reader to appreciate that expressing a preference for St. Augustine's view over the conventional reading of Genesis, Aquinas was not rejecting the literal meaning of Genesis in favor of an allegorical one. For Aquinas the literal meaning was primary, and Genesis was an historical narrative, so there could be no question of doing that. But as we have seen, Aquinas' understanding of the word "literal" was quite different from ours. In his Summa Theologica I, q. 1, article 10), Aquinas discusses the possibility of a word in Scripture having multiple meanings. In this passage, the literal or historical sense of a word in Scripture, which is the primary meaning for St. Thomas, refers to the thing it directly signifies. However, for Aquinas, the author of Scripture is God. Thus each word in Scripture means what God intends it to mean. Hence what God means by "days" is what matters: this is the literal meaning, not the sense understood by the people who first read the book of Genesis.

Why did Aquinas depart from what he called "the more common opinion" (Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, art. 2), which (as he admits) "superficially seems more consonant with the text": the view that the six days followed one another in a chronological sequence? Aquinas' motivation was simple: he wanted to preserve the honor of God from the ridicule of unbelievers: "scripture must be explained in such a way that the infidel cannot mock." What seemed ridiculous to some infidels was the idea that God, after each of his creative acts on the six days, suddenly stopped work until the beginning of the next day, as if he were exhausted. The beauty of St. Augustine's explanation is that it was invulnerable to this cheap jibe: God did everything at once, but He told His angels about it in stages, as they were incapable of understanding the entirety of God's creation in a single instant.

A modern reader might wonder what Aquinas would have made of the "day-age" theory, propounded in the nineteenth century in an attempt to harmonize Genesis with science, had he heard of it. Aquinas might have pointed out that whereas at least some of the Fathers (notably St. Augustine) had endorsed the view that the days were instantaneous, there was no theological precedent for the view that they referred to long periods of time. That would make it a novel view, although not necessarily a false one. St. Thomas might also have criticized the awkwardness of the "day-age" interpretation, since it needs to make the "days" overlap, to accommodate the order in which creatures appear in the fossil record. However, given his statement in his Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, article 2, that "how and in what order" God's work of creation was accomplished did not belong to the substance of faith, I think it is fair to say that St. Thomas would not have regarded the "day-age" view as containing anything contrary to faith.

However, St. Thomas would, in my opinion, be much more favorably disposed towards the view proposed by Professor William Dembski in The End of Christianity (B & H Publishing Group, Nashville, Tennessee, 2009), that the "days" of Genesis represent the order in which God planned the creation in His Mind, as opposed to the chronological order in which the creation took place. As Dembski writes:

The key to this reading [of Genesis] is to interpret the days of creation as natural divisions in the intentional-semantic logic of creation. Genesis 1 is therefore not to be interpreted as ordinary chronological time (chronos) but rather as time from the vantage of God's purposes (kairos).Accordingly, the days of creation are neither exact 24-hour days (as in young-earth creationism), nor epochs in natural history (as in old-earth creationism), nor even a literary device (as in the literary-framework theory). Rather, they are actual (literal!) episodes in the divine creative activity. They represent key divisions in the divine order of creation, with one episode building logically on its predecessor (2009, p. 142).

Dembski's account has obvious affinities with St. Augustine's thinking, and does not therefore constitute a peculiar theological novelty. Nor is it difficult to accommodate with the fossil record.

Third, the very question at the head of the article discussed above (Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book II, Distinction 12, question 1, article 2) makes it clear that Aquinas could not have countenanced evolution. The question reads: "Are All Things Created Simultaneously, Distinct In Their Species?" As we have see, Aquinas was inclined to favor the opinion of St. Augustine, who held that plants and animals were created according to their kind, at the very beginning of time. Interestingly, St. Augustine suggested that the various kinds of plants and animals were originally created as tiny "germinal seeds" which lacked form; later on, God produced their forms (Quaestiones Disputatae de Potentia Dei Q. IV article II, Reply to the Twenty-Second Objection).

Lucas Cranach the Elder, "Paradise," 1533. Bode-Museum, Berlin.

Aquinas expressly taught that Adam and Eve were literal persons, whose bodies were immediately produced by God: Adam's from the slime of the earth, and Eve's from Adam's rib.

Fourth, Aquinas taught that the human bodies of Adam and Eve must have been produced immediately by God: there was no other way, he believed, in which they could have been made. In his Summa Theologica I, q. 91, art. 2, Aquinas addresses the question of whether the human body of Adam was immediately produced by God. In his Reply to objection 3, he describes both "the making of man from the slime of the earth" and the raising of a dead body back to life as "changes that surpass the order of nature, and are caused by the Divine Power alone." (As we saw in "Smoking Gun" number 8, in Part One of my reply to Professor Tkacz, Aquinas' essentialism explains why he believed that simple life forms were incapable of evolving into higher animals - in other words, Aquinas held that Adamís body couldn't have evolved from the body of another kind of animal.)

A recurring feature of Aquinas' discussion of the creation of man and woman is the extraordinary reverence which he accords to Scripture. Thus when discussing whether the creation of the first man (Adam) was fittingly described in Scripture, Aquinas enumerates no less than five common objections to the appropriateness of the Scriptural account, but instead of giving his customary one- or two-paragraph response to these objections, he responds in a single short sentence (Summa Theologica I, q. 91, art. 4):

On the contrary, Is the authority of Scripture.

Evidently, Aquinas feels that this response suffices. The Bible says God made man that way; so that settles it. End of story. Aquinas feels no need to make a case for Scripture's authority, although he did go on to address the five objections which he had raised.

Similarly, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 92, article 2, Aquinas listed three Scriptural reasons, plus one philosophical argument, as to why it was appropriate that Eve should have been produced from the body of Adam, as described in the second chapter of Genesis. In the following article, he gives two reasons why Eve should have been formed from Adam's rib, rather than his head or feet, and cites the authority of Scripture to settle the matter:

On the contrary, It is written (Genesis 2:22): "God built the rib, which He took from Adam, into a woman."

Subsequently, in his Summa Theologica, I, q. 92, article 4, Aquinas explains why only God could have done the job:

Now God alone, the Author of nature, can produce an effect into existence outside the ordinary course of nature. Therefore God alone could produce either a man from the slime of the earth, or a woman from the rib of man.

Jan Breughel the Elder, "Paradise," 1620. Gemaldgalerie, Berlin.

Aquinas believed that Paradise was a literal place, with a literal Tree of Life and a Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Fifth, Aquinas believed that Adam and Eve were placed in a literal Paradise, which was a real place. Aquinas felt compelled to reject the view held by some Christians, that Paradise was a purely spiritual state, on the grounds that Genesis 2 was clearly written as an historical narrative, and should therefore be interpreted as such. As he wrote in his Summa Theologica, I, q. 102, article 1:

I answer that, As Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xiii, 21): "Nothing prevents us from holding, within proper limits, a spiritual paradise; so long as we believe in the truth of the events narrated as having there occurred." For whatever Scripture tells us about paradise is set down as a matter of history; and wherever Scripture makes use of this method, we must hold to the historical truth of the narrative as a foundation of whatever spiritual explanation we may offer. And so paradise, as Isidore says (Etym. xiv, 3), "is a place situated in the east, its name being the Greek for garden."

Just how seriously St. Thomas took the physical reality of Paradise can be seen in his response to the objection (in the same article) that explorers, despite having traversed the entire world, had never found Paradise. Aquinas answers that Paradise still exists, but it is in a secluded location, which no-one can enter:

Reply to objection 3. The situation of paradise is shut off from the habitable world by mountains, or seas, or some torrid region, which cannot be crossed; and so people who have written about topography make no mention of it (Summa Theologica I, q. 102, art. 1, reply to obj. 3).

Likewise, when discussing the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, St. Thomas insists (in the same article) that they were both real, material trees, but that in addition to their literal significance, these trees also had a spiritual significance:

The tree of life is a material tree, and so called because its fruit was endowed with a life-preserving power as above stated (question 97, article 4). Yet it had a spiritual signification; as the rock in the desert was of a material nature, and yet signified Christ. In like manner the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was a material tree, so called in view of future events; because, after eating of it, man was to learn, by experience of the consequent punishment, the difference between the good of obedience and the evil of rebellion. It may also be said to signify spiritually the free-will as some say.

Aquinas also taught that the Garden of Eden, being an earthly Paradise, must have been situated somewhere with an equable climate: "we must hold that paradise was situated in a most temperate situation, whether on the equator or elsewhere" (Summa Theologica I, q. 102, article 2). The equability of the climate was especially important, because St. Thomas believed that extremes of heat and cold were the main cause of aging and bodily generation, which would not have occurred in Paradise.

A literal tree of life, a literal tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and a Garden of Eden that's still out there somewhere, near the Equator ... one could hardly ask for a more literal interpretation of the Genesis account!

Now, a "modern Thomist" might object that Aquinas' discussion of Paradise is predicated on the assumption that the account in Genesis 2 is "set down as a matter of history" - i.e. that it was intended to be an historical narrative. But many scholars now claim that Genesis 2 was originally intended to be a figurative account, rather than a narrative - in which case, Christians are no longer bound to treat the Biblical account of Paradise as an historical one, as Aquinas felt he had to.

However, the view that Genesis 1 to 11 was not originally intended as an historical narrative is quite untenable, for a whole host of reasons relating to style and literary form. I refer the reader to the following online articles:

(1) Genesis 1-11 as Historical Narrative by W. Gary Phillips and David M. Fouts.

(2) Is Genesis poetry-figurative, a theological argument (polemic) and thus not history? by Dr. Don Batten, Dr. David Catchpoole, Dr. Jonathan D. Sarfati and Dr. Carl Wieland.

(3) The Biblical Hebrew Creation Account: New Numbers Tell the Story by Dr. Stephen W. Boyd.

(4) Five Arguments for Genesis 1 and 2 as Straightforward Historical Narrative by the Creation Science Association of British Columbia.

(5) Is Genesis Poetry or Historic Narrative? by Helen Fryman.

Thus it would be utterly mistaken to suppose that if Aquinas were alive today, he would abandon his literal interpretation of the Biblical account of Paradise, found in Genesis 2.

Laurent de la Hire, "Job restored to prosperity," 1648. The Chrysler Museum, Norfolk.

According to Aquinas, Christians are bound to believe that Job was a real, historical person, and not an allegorical figure.

Sixth, Aquinas clearly taught that the characters in the Bible were literal historical figures. This is readily apparent from the Prologue of Aquinas' Commentary on Job, where he alludes to the view (held by some Jewish scholars in his day) that the book of Job was intended as nothing more than "a parable made up to serve as a kind of theme to dispute providence, as men frequently invent cases to serve as a model for debate," and then forcefully rejects it. The Jewish philosopher and Rabbi Moses Maimonides (1135-1204), following other Jewish sages, had asserted in his Guide for the Perplexed, Part III, chapter 22, that the book was not factual, but a work of fiction, designed to teach us about Providence. Maimonides based his denial of the historicity of Job on the total absence of biographical information in the book concerning Job's ancestry, his parents and when he lived. All we are told about Job is that "In the land of Uz there lived a man whose name was Job" (Job 1:1, New International Version). In his Prologue, St. Thomas rejects the view that the book of Job is an allegory, on Scriptural grounds:

Although it does not matter much for the intention of the book whether or not such is the case, still it makes a difference for the truth itself. This aforementioned opinion seems to contradict the authority of Scripture. In Ezechiel, the Lord is represented as saying, "If there were three just men in our midst, Noah, Daniel, and Job, these would free your souls by their justice." (Ez. 14:14) Clearly Noah and Daniel really were men in the nature of things and so there should be no doubt about Job who is the third man numbered with them. Also, James says, "Behold, we bless those who persevered. You have heard of the suffering of Job and you have seen the intention of the Lord." (James 5:11) Therefore one must believe that the man Job was a man in the nature of things.

Note the language used here: "there should be no doubt about Job"; "one must believe that Job was a man." These are very strong words.

Now, if St. Thomas insisted that Job could not be allegorized away, then we can be sure he would have insisted even more strongly that the Biblical patriarchs from Adam to Noah were real historical figures. Unlike Job, their ancestry is given in Genesis 5; additionally, some of them are mentioned elsewhere in Scripture several times. For instance, Enoch is mentioned in Hebrews 11:5 and Jude 1:14-15, and Noah in Ezekiel 14:14-20, Sirach 44:17-18, Matthew 24:37, Luke 17:26, Hebrews 11:7, 1 Peter 3:18-22 and 2 Peter 2:5. And in view of the fact that Noah, the Ark and the Flood are explicitly referred to by Jesus Christ in two of the Gospels (Matthew 24:37-39, Luke 17:26-27), as well as in 1 Peter 3:20 (see also 2 Peter 2:5), we can be sure that St. Thomas would have regarded the literal historicity of the Flood as something which Christians could not question.

Additionally, Aquinas explicitly mentions three of these Biblical patriarchs: Adam's son Seth, who Scripture tells us was born after Cain murdered Abel and was banished by God; Enoch, who is identified in the book of Jude as "the seventh from Adam" (Jude 1:14), since he is the seventh person listed in the genealogy from Adam to Noah in Genesis 5; and Noah, who was warned by God to build an ark in order to be saved from the Flood that would destroy the rest of humanity. Let's look at each of these figures in turn.

(1) Seth. In discussing the question of whether angels exercise vital functions when they assume human bodies, Aquinas anticipates an objection relating to the Biblical account in Genesis 6:1-4, where the "sons of God" mated with the "daughters of men," causing them to give birth to giants (Nephilim), who were the mighty men of old, men of renown. This Biblical passage seemed to indicate that angels were capable of mating with human beings. In his reply, Aquinas does not contest the historicity of the story. Instead, he offers what he regards as a more sensible literal interpretation, which he borrows from Augustine's City of God, Book XV. The sons of God were the descendants of Adam's third son, Seth, while the daughters of men were the descendants of his first son, Cain, the first murderer in history:

Hence by the sons of God are to be understood the sons of Seth, who were good; while by the daughters of men the Scripture designates those who sprang from the race of Cain (Summa Theologica I, q. 51, art. 3, reply to obj. 6).

For Aquinas, then, there was no doubt that Seth and Cain were real historical individuals.

(2) Enoch. Aquinas also asserted the historicity of Adam's great-great-great-great-grandson, Enoch, who is said to have been taken up to heaven at the age of 365 (Genesis 5:23-24; Hebrews 11:5). Here is what Aquinas writes about Enoch and Elijah (Elias) in his Summa Theologica III, q. 49, art. 5 when discussing the question of whether Christ opened the gate of Heaven to us by His passion. Aquinas anticipates the objection that some of the prophets, such as Elijah (Elias), had already been taken up into Heaven, long before Christ's suffering and death on the cross, and replies that they did not go to the same heaven as the one opened by the saving death of Christ:

Reply to Objection 2. Elias was taken up into the atmospheric heaven, but not in to the empyrean heaven, which is the abode of the saints: and likewise Enoch was translated into the earthly paradise, where he is believed to live with Elias until the coming of Antichrist.

Here, St. Thomas teaches that these two prophets are not in the empyrean heaven (i.e. the supernatural realm) but are in the atmospheric heaven. According to Aquinas, these two men are now waiting for their encounter with the Antichrist, in the earthly Paradise that God originally created for Adam. As readers will recall, Aquinas held that Paradise still existed, in some secret, inaccessible place on Earth.

The point I wish to make here is that for Aquinas, the historicity of Enoch and Elijah was beyond question. The accounts in Scripture were "set down as matter of history; and wherever Scripture makes use of this method, we must hold to the historical truth of the narrative" (Summa Theologica I, q. 102, art. 1).

(3) Noah. Aquinas alludes to Noah and the ark several times in his Summa Theologica. For instance, he asserts that "Christ was born of those alone who descended from Noah through Abraham, to whom the promise was made" (Summa Theologica I-II, q. 98, art. 6, obj. 3), and he also cites St. Peter's Scriptural reference to "the days of Noe, when the Ark was being built" (Summa Theologica III, q. 52, art. 3, reply to obj. 3). However, the decisive proof that St. Thomas regarded the existence of Noah as a fact that no Christian could deny can be found in the Prologue of Aquinas' Commentary on Job), where he writes:

In Ezechiel, the Lord is represented as saying, "If there were three just men in our midst, Noah, Daniel, and Job, these would free your souls by their justice." (Ez. 14:14) Clearly Noah and Daniel really were men in the nature of things and so there should be no doubt about Job who is the third man numbered with them.

We may therefore safely conclude that Aquinas believed that no true Christian could doubt the existence of the patriarchs.

Joshua Reynolds, "The infant Samuel," 1776. Musee Fabre, Montpellier.

According to Aquinas, to deny that Samuel was the son of Elcana (as the Bible narrates) would be tantamount to claiming that Scripture is false.

Seventh, Aquinas taught that no Christian could deny the "begats" in Scripture. In Genesis 5, it is written that Adam begat Seth, who begat Enosh, who begat Kenan, who begat Mahalalel, who begat Jared, who begat Enoch, who begat Methuselah, who begat Lamech, who begat Noah. Evidence that Aquinas insisted on a very literal interpretation of these "begats" can be found in his Summa Theologica I, q. 32, article 4, where he asserted that the Scriptural statement that Samuel was not the son of Elcana was indirectly "against faith":

A thing is of faith, indirectly, if the denial of it involves as a consequence something against faith; as for instance if anyone said that Samuel was not the son of Elcana, for it follows that the divine Scripture would be false.

Some Christians, including old-earth creationists, have recently suggested that the Hebrew word "begat" in the Old Testament need not denote a father-son relationship. They claim that "X begat Y" could mean, "X was an ancestor of Y." However, this speculation is utterly unfounded. As Larry Pierce and Ken Ham point out in their article, Are There Gaps In The Genesis Genealogies?:

Nowhere in the Old Testament is the Hebrew word for begat (yalad) used in any other way than to mean a single-generation (e.g., father/son or mother/daughter) relationship.