The Battle of Crampton’s Gap: “Key Point of the Whole Situation”

Why did the armies come to SouthMountain?

Gen. Robert E. Lee moved his Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland for many reasons, paramount among them being the Confederacy’s long-standing desire for intervention by Great Britain and France, world powers of the day, to obtain foreign recognition and material aid against the far stronger Northern states waging war for its downfall. By invading Union soil, Lee also hoped to relieve Virginia from war’s cost, evoke sympathy from disaffected Northerners, impact upcoming mid-term Congressional elections, create panic in the stock market, and broadly startle the world at large as a nation worth noticing. With so much at stake, the climate would never be better for Southern independence.

To accomplish this Lee moved northward, intent on drawing Union forces after him, with the idea of confronting his adversary on ground of his choosing while threatening Pennsylvania, this after driving Union forces back onto Washington following the Second Battle of Manassas in late August. Gen. George B. McClellan was hastily given the task of reforming his Army of the Potomac, then ordered to pursue Lee and bring him to bay with little or no knowledge of where Lee had gone or what he intended.

What was the turning point?

Pausing at Frederick, Maryland to rest his troops, Lee penned his Special Orders No. 191 outlining campaign objectives. The Confederate army would march westward across South Mountain. Half the army under Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson would descend upon Federal garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry, (West) Virginia, while the other half, under Gen. James Longstreet accompanied by Lee, would continue west to Hagerstown near to the Pennsylvania state line. Lee would leave a rearguard at South Mountain under Gen. D. H. Hill to watch for pursuit. In this fashion, Lee the gambler broke the cardinal military rule of never splitting one’s forces in the face of a superior enemy—with or without a mountain intervening.

A copy of Lee’s orders was unaccountably left behind at Frederick, falling into McClellan’s hands on Saturday, September 13, 1862. Armed with the “Lost Order,” McClellan devised surgical counter-strategy to compromise Lee’s movements in mid-stride and to perhaps close the war. During the postwar era, veterans and historians agreed that the finding of the Lost Orders was without doubt the turning point of the campaign, perhaps of the entire war due to the then favorable climate for foreign intervention.

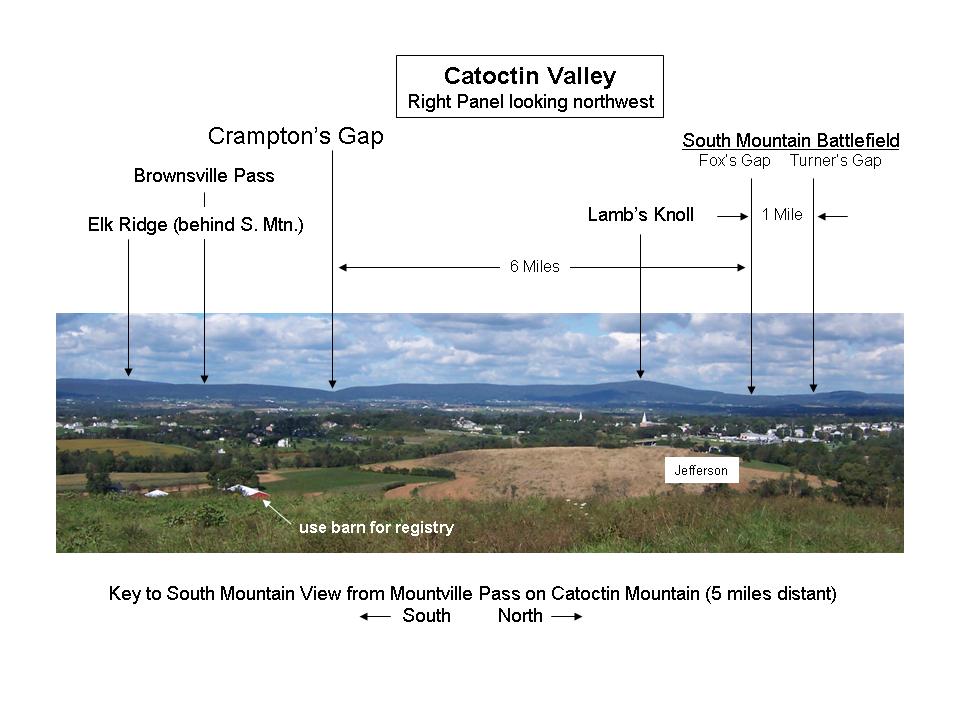

To use a boxing metaphor, McClellan now struck at three road crossings on SouthMountain where he could best threaten Lee. While his strong right wing powerfully smashed into Hill’s rearguard at Turner’s Gap, where the National Pike crossed—preceded by a quick right jab flank march at Fox’s Gap, one mile south—he ordered a left hook at Crampton’s Gap, six miles to the south, intent on driving a wedge between the widely separated halves of Lee’s army. His left could then relieve Harpers Ferry and drive westward to Sharpsburg, cutting off Lee. In this way, McClellan could confront Lee beyond South Mountain with startling numerical advantage. After vanquishing Longstreet’s half of the army, he could then descend on Jackson with still greater advantage, assuming the latter would stand his ground. Though his counter-strategy was sound, McClellan was not well served by his wing commanders, generals Ambrose Burnside and William Franklin.

When and where did fighting occur? For how long?

Sunday, September 14, 1862. Assaults on Turner’s and Fox’s gaps were orchestrated by Burnside, overseen by McClellan at the former near the village of Bolivar. Fighting began at 9 A.M., what was planned as seizure of the mountain crest at Fox’s Gap by Reno’s Ninth Corps, followed by an advance along the ridge to flank Hill out of Turner’s Gap. Hill rushed Gen. Samuel Garland’s troops to Fox’s Gap to meet this threat, sparking a bloody standoff south of the crossroads during which Garland was mortally wounded. Fighting was renewed by the Ninth Corps around 2 P.M., and again at 4, continuing without success until nightfall. Though yielding ground, Confederate reinforcements stubbornly barred the way. Near nightfall Reno angrily rode to the summit to personally investigate the holdup and was killed by a Confederate sniper. Further disheartened by his death, Federal troops were unable to make headway toward Turner’s Gap as originally planned.

Meanwhile, Gen. Joseph Hooker’s First Corps had moved directly on Turner’s Gap via the National Pike and by another flank march through the area of Frosttown north of that gap. Marching out of Middletown, Hooker’s forces did not come to grips until about 4 P.M. As at Fox’s Gap, Confederate resistance was desperate and heroic. Outnumbered and hard pressed, Hill was reinforced late in the day by Longstreet’s brigades hurriedly counter-marched in mid-stride from Hagerstown. As darkness approached, Union troops were prevented from seizing the entire summit, forced to sleep on their arms. Confederates still clung to nearly a mile of the mountain ridge line.

To the south, Franklin’s Sixth Corps easily burst through Crampton’s Gap in total victory at about 6 P.M., after marching through Jefferson to Burkittsville. The attack however had been launched too late in the day to capitalize on its success before nightfall. Sixth Corps troops could still hear firing at the northern gaps after Crampton’s Gap had fallen.

How many troops were involved?

Union present-for-duty figures are reasonably dependable. Confederate reports however are far less accurate or do not exist. Estimates yield a broad ratio of 3 to 1 in favor of Union forces at Turner’s and Fox’s gaps. Crampton’s Gap figures are more clearly defined, yielding 6 to 1 odds in favor of Union troops. Overall figures for the three gaps on South Mountain reveal odds of 3.6 to 1 in favor of Union forces.

|

|

Strengths |

CONFEDERATE |

Strengths |

|

First Corps, Turner’s Gap |

14,800 |

D. H. Hill’s Division (est.)

|

5,800 |

|

Ninth Corps, Fox’s Gap |

13,000 |

Longstreet’s brigades (est. reinforce)

|

3,300 |

|

Sixth Corps, Crampton’s Gap |

12,800 |

Crampton’s Gap |

2,100 |

|

Total |

40,600 |

Total |

11,200 |

Total troops involved on South Mountain: 51,800

How many casualties were inflicted?

Union casualty reports are mostly reliable. Confederate casualties however are nearly impossible to determine due to poor or nonexistent after-action returns. Southern casualties were reported in total for the entire campaign, irrespective of a particular engagement. Totals are largely inseparable. The following figures were collected from all available returns and estimates (killed, wounded, missing, prisoner of war):

|

|

Losses |

CONFEDERATE |

Losses |

|

First Corps, Turner’s Gap |

933 |

Turner’s Gap |

unknown |

|

Ninth Corps, Fox’s Gap |

858 |

Fox’s Gap |

unknown |

|

Sixth Corps, Crampton’s Gap |

538 |

Crampton’s Gap |

873 |

|

Total |

2,329 |

Total

(2,685 est. at

Turner’s & Fox’s) |

3,558 |

Total casualties inflicted on South Mountain: 5,887—5% of Union strength, 31% of Confederate strength

Who won? Who lost?

In calculating success or failure, we must examine South Mountain as two disconnected battles fought for wholly separate strategic objectives. They were so viewed by both Lee and McClellan. The Battle of South Mountain proper (i.e., Turner’s and Fox’s gaps) though styled a Union victory by McClellan, was in fact a tactical defeat for Union forces. The Ninth Corps flanking maneuver at Fox’s Gap was effectively blunted at great cost. McClellan’s main drive through Turner’s Gap also ground to a halt at day’s end. Confederate troops, though highly disordered by combat, still clung to portions of the summit and western slope when firing ceased.

Later that night Lee wisely, though reluctantly, evacuated this portion of the mountain after learning of the result at Crampton’s Gap. From the Confederate viewpoint, disaster had been narrowly averted. McClellan on the other hand had run head-on into an impenetrable wall at South Mountain, dramatically forestalling his coming to grips with Lee before the latter could reunite with Jackson. McClellan’s only tangible gain at South Mountain was the halting of Lee’s westward march. Therefore, South Mountain is properly defined as a strategic standoff for both armies, though it just barely qualifies as a tactical victory for Lee via D. H. Hill’s intrepid rearguard stand. Fighting at Turner’s Gap and Fox’s Gap can be fairly described as irresistible forces pitted against immovable objects.

In counterpoint, Crampton’s Gap was undeniably a Union victory, the sole undisputed success of the campaign, and in fact the first victory over any portion of Lee’s army thus far in the war. Confederate commands engaged there were badly demoralized and scattered into the night. Nothing remained to block Franklin’s way to Sharpsburg, excluding his mandate to relieve Harpers Ferry. For McClellan, Crampton’s Gap and SouthMountain were one win and a tie.

How did Crampton’s Gap impact Union and Confederate campaign plans?

In the early, sleepless hours of Monday, September 15, Lee learned of the shocking Crampton’s Gap setback and hastily evacuated his remaining troops, still doggedly clinging to Turner’s and Fox’s gaps. Only then did he apprehend that McClellan was attempting to keep Longstreet and Jackson apart. Had Crampton’s Gap Confederates held on as at the other gaps, Lee would have been allowed time to reunite his forces and continue westward, perhaps offering McClellan battle farther to the northwest on ground of his own choosing as originally planned. In this event, the “Lost Order” would have merely reduced Lee’s safe distance from McClellan, underscoring the need for further rapid footwork.

Battle at the two northern gaps arrested Lee’s progress to Hagerstown. Defeat at Crampton’s Gap soundly impressed upon him the urgency of rejoining Jackson, still preoccupied with the siege of Harpers Ferry. Lee had to get Longstreet out of harm’s way before McClellan could corner him. He was therefore obliged to race to Sharpsburg where Jackson could join him via Shepherdstown Ford. Franklin declined to get between Longstreet and Jackson as ordered, even after the fall of Harpers Ferry, allowing Lee to reassemble unmolested. McClellan’s “wedge” had been abandoned, forcing his army to swing to the southwest through Boonsboro and Keedysville on Franklin’s rooted pivot. Lee in fact showed no desire to meet McClellan at Sharpsburg under the circumstances until he heard of Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry, freeing him to rejoin Lee. Only then did Lee decide to confront McClellan head-on at Antietam Creek in what became the bloodiest single day of the war, a stubborn gamble to salvage something of value from a campaign gone horribly awry.

On September 17, Antietam too became a fearful, tactical standoff at a place Lee never dreamed of fighting. In a very literal sense, Crampton’s Gap directly precipitated the Battle of Antietam, as well Lee’s ultimate return to Virginia. But it can be argued that Lee survived to fight another day because Lost Order advantages were not fully exploited. Modern historians have tended to blame McClellan exclusively for these lost opportunities, when it was his subordinates rather who had the “slows.”

How did Crampton’s Gap affect the war’s progress and outcome?

Crampton’s Gap conclusively halted Lee’s campaign into the North, nullifying multiple political benefits he hoped to derive. It forced him into a set-piece battle at Antietam, results of which cost him dearly, having just the opposite effect on Northern and foreign opinion he and his infant nation had so earnestly hoped to influence.

Fully cognizant of Confederate overtures for European aid, President Abraham Lincoln had long anticipated a Union victory that would facilitate a political design calculated to isolate the South. Though Antietam was a tactical standoff, Lee’s abandonment of Maryland lent the appearance of victory for Federal arms. From this tentative platform Lincoln issued his preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation just five days after Antietam, a document that shifted Union war aims onto political ground morally repugnant to Great Britain and France. Abolition of slavery had now become an objective equal in weight to restoration of the Union. As a result, a British or French referendum on Southern recognition was indefinitely postponed. Thus stigmatized, the Confederate States continued to search in vain for fading European sympathy and support. Lincoln’s canny maneuver adroitly deflected the most dangerous impediment to crushing the Confederacy. From that moment the North was free to wage punitive war, confident that the Confederate States would stand or fall alone, solely through their own inferior resources.

Lee’s 1863 campaign into Pennsylvania was a desperate replication of his Maryland exploits. This time he was not hindered by lost orders or a Federal garrison planted squarely astride his extended line of communication and supply. By then the impetus for campaigning in the North had passed, namely the quest for Northern disaffection and foreign recognition.

Where he only need seriously embarrass Federal forces for crucial diplomatic gain in 1862, at Gettysburg he was vitally tasked with destroying the Union army without hope of foreign intervention. Historians habitually characterize the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg as the “high-water mark” of the Confederacy, when in fact the events of 1862 predestined war’s outcome. Gettysburg was without question the military high-water mark of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. But the momentous 1862 Maryland Campaign, strategically pivoted on the Lost Order, Crampton’s Gap and Antietam, was the indisputable pinnacle of Confederate diplomatic achievement, as well any hope for independence, nationhood or sovereignty.

TIMOTHY J. REESE served eighteen years on the staff of the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History. He is the author of Sykes’ Regular Infantry Division, 1861-1864 (1990) and Sealed With Their Lives: The Battle for Crampton’s Gap, Burkittsville, Maryland, Sept. 14, 1862 (1998). He has been associated with the Crampton’s Gap battlefield at GathlandState Park, South Mountain since 1975.

© T.J. Reese, 2000

| History of the War in the Valley | Historic Places | Civil War Tour | Shenandoah Valley Museums | Soldiers and Civilians | Site Map | Shenandoah Valley Links |