Captain John Smith's Virginia Adventures:

The Survival of the Jamestown Colony

and the Exploration of Virginia's Tidewater

With extensive references drawn from

William M. Kelso's "Jamestown, The Buried Truth", 2006

and

John M. Thompson's (editor) "The Journals of Captain John Smith", 2007

(additional discussion, topics and resources will be added in the future--suggestions are welcomed!)

Follow this link to Virginia's First Peoples,

to find how

your school or group can schedule a presentation free of charge.

I do so free of charge because it really is that important to me.

Shouldn't it be just that important to all of us?

Sincerely,

David Stone Sweet

Suggestions for Essays, Classroom

Discussion, Oral Presentations and Reports

When did mankind first come to the Americas, and from where?

What IS Archaeology?

Issues of Treaty Reform and American Indian Sovereignty

>>>>> STONE'S ARCHAEOLOGY <<<<<

Topics Discussed Are

Ethical Responsibility in Collecting

The mystery of North Carolina's Hardaway-Site Campfire Pits

The Significance of Projectile Point Flaking Patterns

Beveling of Points and Knives

Clovis Settlement Patterns in Southeastern Virginia

Poor weather delayed the ships' progress from the English Channel long enough

to deplete the provisions carried for their survival in Virginia. Accusations

of mutinous behavior, spurred by jealousies over Smith's military experience,

caused Smith to be locked in chains for most of the journey across the Atlantic

It was late December in the year 1606

when three ships bearing 144 passengers and crew sailed from the Thames River and out into the Atlantic Ocean, embarking upon a perilous mission to establish an outpost in a place called Virginia. Claimed by Spain 36 years earlier in 1570, the intrepid voyagers sought to profit by the same means the Spanish had so done all across central and South America. The riches found there were already legend, and this expedition meant to find and lay claim to similar wealth--right under Spain's very nose!

Gambling on speculative rumor and chance, a group of investors calling themselves The Virginia Company of London financed the expedition with high hopes of finding gold, silver and more. A passageway to the pacific was among the primary goals--a short-cut to the Orient promised even greater profits for the burgeoning company. This was no great embryonic vision of 'America from sea to shining sea' that these men carried within their hearts, but only a get-rich-quick scheme!

Those gentlemen-investors who came to Virginia sought only personal wealth--for the most part they were from fairly well-to-do or even wealthy families, but they themselves, not being first-born heirs, did not stand to inherit their familys' fortunes. Holding airable lands that turned enough profit for them to live more or less comfortably by, each invested in this venture for his passage to Virginia, hoping to return in short order with wealth beyond their dreams. Of all who made the journey, most perished, a few returned to england broke or in shame, and only one would become world famous for his efforts, if not wealthy.

His name was John Smith. Born a farmer's son, he ran away from home by age 16 and restlessly wandered over europe and Asia as a soldier of fortune, serving Dutch and Austrian masters. Smith learned the arts of war and fighting, of bluffing and bravado's elemental keys to success, and how to size up an enemy. His skills at martial arts and his bravery often tested his strength and strategizing abilities--key skills that enabled him to test his metal successfully in the American wilderness. He is known to have bested three Tirkish warriors with pistol, sword and battle axe.

Sold into slavery in Constantinople, he killed his master and, siezing his horse, made his escape into Russia and on to further adventures, eventually making his way back to England. Not the least shy of making himself known for his exploits or of seeking new adventures, Smith found himself sought out by members of The Virginia Company for this perilous voyage. Of John Smith, Thompson records: "...he probably knew poet Michael Drayton's incitement,

"To get the pearl and gold / And ours to hold / VIRGINIA / Earth's only paradise."

Smith's appatite whetted for new lands and adventures, he boarded the Virginia company's 116ft flagship, Susan B. Constant, bound for Virginia with two other, smaller vessels, the Godspeed and Discovery. Now, being a self-made man-at-arms, a true warrior-spirit flowed in his veins. Knowledge and experience had taught him the bare-bones rules of life, and his tales of bravado most likely overshadowed others' self-styled superiority of birth-right. As can be expected, those of higher birth amongst the voyagers took great offense to his at times grating arrogance--and it is as likely Smith did not appreciate theirs, either!

The Settlers first landing in Virginia at Cape Henry, now the site of First

landing State Park. There, Indians and the settlers clashed, the first of

many confrontations yet to come. It was an inauspicious begining...

Arrows such as Stone is seen holding here were the primary hunting weapon used

by the Powhatan Indians. Tipped here with a crystal-quartz point fixed into

place with hide-glue and charcoal for glue (a carbon-fiber resin) and sinew,

and fletched with wild turkey feathers, the arrow would spin in flight much as

a rifled bullet will do. (two technologies we use today to

make car panels,

fishing rods and to assure the true flight of a bullet against cross winds)

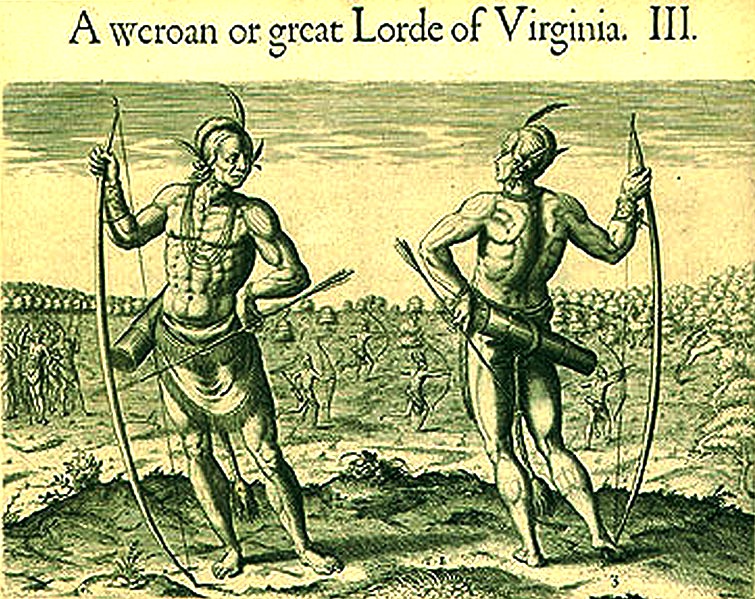

Encountering trouble upon their first landing on Virginia soil, two colonists were injured by a party of five Indians. The point of land at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay where this first landing took place was christened Cape Henry, and a cross was raised to mark England's claim. The ships left Cape Henry after a few days' rest, and sailed onward into the mouth of a great river that was thus named the James River after Englands' ruler King James. Directed by the Virginia Company to establish a colony at least 100 miles from the ocean--to avoid any confrontation with the Spanish--a place was shortly found that proved defensible, although far short of the requisite 100-mile statute. A strong fort was thought to incite resentment among the Indians, so tents were pitched and camp was set up. Although much other work was required to establish the colony, most of the men set about to digging for the hoped-for gold, finding glittery stuff in enough of the soil to excite beyond reason--it all turned out to be worthless dirt!

These early firearms were not particualry accurate at any distance, and while

they could be quite lethal at close range, their effect was more to create

frightening noise and smoke, and to injure any who happened to be in the way

of their discharge...if they fired at all, damp powder being a problem at times

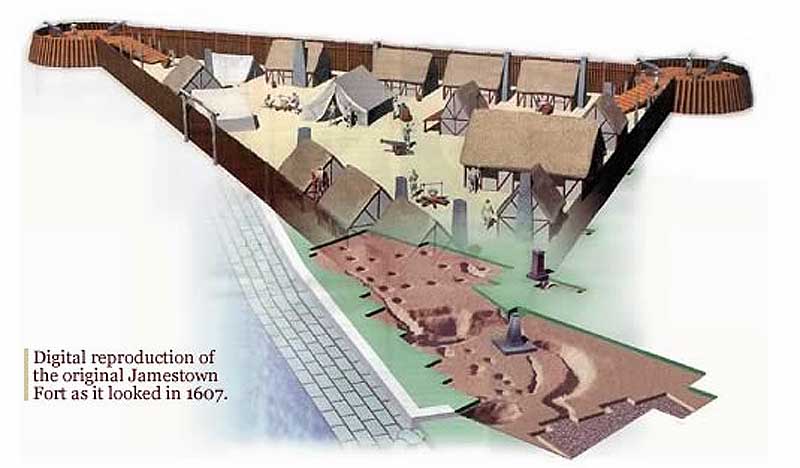

Following some several weeks of relative calm, Captains Newport and Smith, along with 22 others, set out from the colony to explore the James River's farthest navigable reaches. No passage to the orient was found, nor gold or other riches. Upon their return to Jamestown it was learned that some 200 warriors had attacked the settlement, kiilling one and injuring 17. Several Indians were reported injured or killed by scattered gunfire, but it wasn't until one of ths ship's cannons fired bar-shot towards the Indians, shattering a tree-top before their unbelieving eyes, did they retreat into the woods. Plans for a fortified enclosure were immediately put into action. Laboring under the hot sun, in a mere 19 days the colonists completed a triangular enclosure around their camp. Trees were cut and hewn into long, sturdy posts, and these were sunk into some 900 feet of trench dug to support them.

Provisions scarce, water of poor quality, and rampant disease all took their

toll upon the colonists as they erected a fort under continual observation and

frequent arrow-attacks. In a mere 19 days the enclosure was completed from

piles weighing as much as 800lbs each

The work progressed under difficult conditions--Indians sought to pick off the colonists one by one with arrows shot from conceiled positions, they often darting away before a musket could be fired back. Adding to the difficulties already taking their toll, provisions were in short supply.

In Smith's words (here edited by John M. Thompson in his "The Journals of Captain John Smith"), was the situation:

"While the ships stayed, our allowance was somewhat bettered by a daily proportion of biscuit, which the sailors would pilfer to sell, give or exchange with us for money, sassafras, furs, or love. But when they departed, there remained neither tavern, beer house, nor place of relief but the common kettle. Had we been as free from all sins as we were from gluttony and drunkeness, we might have been cannonized for saints. But our president would never have been admitted (canonized) for engrossing to his private oatmeal, sack, oil, aqua viae, beef, eggs, or whatnot. But the kettle? That indeed he allowed equally to be distributed. And that was half a pint of wheat, and as much barley boiled in water for a amn a day--and this (having fried some 26 weeks in the ship's hold) contained as many worms as grains, so that we might truly call it rather so much bran than corn. Our drink was water, our lodgings castles in the air. With this lodging and diet, our exteme toil in bearing nd planting palisades, so strained and bruised us, and our continual labor in the extremity of the heat had so weakened us, s were cause sufficient to have made us miserable in our native country, or any other place in the world"

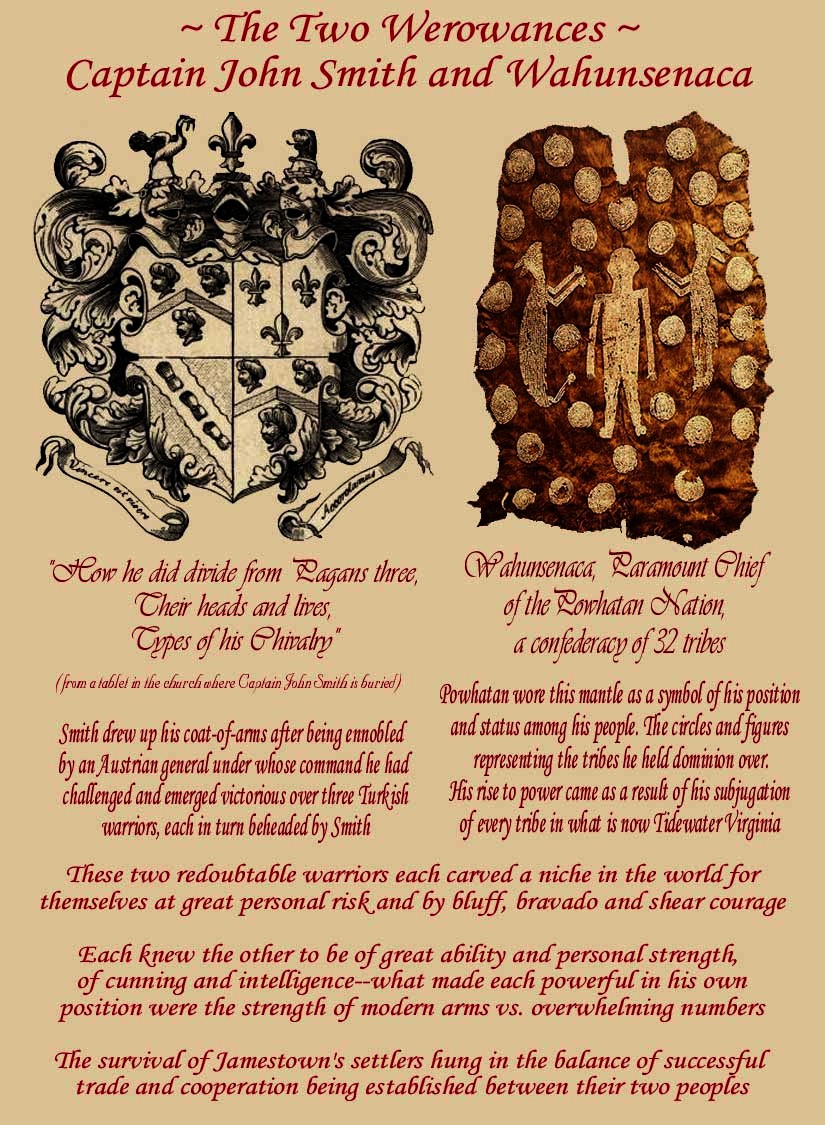

Political diplomacy and bravado, quick thinking and cunning played key rols in Smith's abilities to obtain from the Powhatans the required provisions to keep the colonists alive. During Smith's explorations, dubious leadership and intrigues cause havoc in efforts to obtain and maintain suitable food supplies--many perished because of these factors, and only Smith's timely return to the colony kept the rest alive on more than a few ocassions. In one significant drama, with Captain Newport still presiding over the council and Captain Smith managing the relations with the Powhatans, a journey was made to Werowocomoco, Wahunsenaca's seat of power over his confederacy of tribes, on the York River in what is now Gloucester County. Wahunsenaca understood something of the rivalries for power among the colonists, and sought to take advantage of this when Captain Newport pressed that he was the one to be dealt with in trading that day.

Smith sought to stem the sailors' illegal trading of copper and the colony's

stores of other trade goods--and the colonists' iron tools--to the Powhatans.

The colony's survival depended upon maintaining a high market value for these

items, and the sailors' trading so devalued them that Smith was hard-pressed

to obtain the much needed provisions from local tribes. Explorations revealed,

among many other things, more distant tribes to trade with, being less affected

by their trade goods' sharply declining valuation

Wahunsenaca would not make any offers for the trade goods brought to his village that day unless Captain Newport laid out all he had for Wahunsenaca to see. Smith unsuccessfully tried to disuade Newport of this, but Newport would not listen. Disdaining to consider any of it meaningful to him, he offered but a mere four bushels of corn for the entire array of goods laid out--a paltry price he knew only too well, knowing as he did that the colony needed his corn far more than he needed their trade. It was a mistake on Newport's part to not have heeded Smith's more careful considerations.

Smith stood aside, meanwhile idly fingering strings of deep blue beads half-tucked into his pocket, caught Wahunsenaca attentions with them. Avowing these beads to be the treasured possessions of crowned heads of Europe, that they were suited only for royal hands, Wahunsenaca--perhaps seeing how Newport's trading abilities were less than his own and desiring to stir things a bit between the two Englishmen as well as to demonstrate his preferences for whom he would bargain--offered Smith a cnsiderable recompense for the beads he coveted. The shallops which carried the colonists to the Chief's village were thusly loaded to the gunwals with meats, corn, and such fowl and other foodstuffs as to assure the colony's continued survival for a good while longer than was offered by Newport's trading abilities had won them. Again and again Wahunseaca and Smith played such roles in colonial/Indian diplomcy that clearly established appreciation of the others' leadership and prowess.

The means to Jamestown's initial survival came in the form of foods traded

from the Powhatan Indians--and from Captain John Smith's accute understanding

of dealing with the indians for these much needed provisions

Captain Newport left for England that summer, laden with more useless dirt than planking and other manufactured goods, and returned again in January of 1608. The first of many subsequnt cracks in the colony's leadership became evident during Captain Newport's absence. Wingfield was caught hoarding food while other starved, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold took sick and died August 1st. George Kendall was held a prisoner with Wingfield aboard the pinnace, a prisoner for heinous conduct (he was later executed as a spy for the Spanish). Wingfield was sent back to england in complete disgrace. Captain John Martin was so often sick, and of such poor leadership qualities that he was of no use. This left Ratcliffe, a man of little personal abilities, presiding along with Martin over the colony.

Smith, charged with managing supplies and overseeing such neccessary works set about directing the production of planks for building houses, binding of thatch and thatching of the houses, and bearing the greatests tasks upon himslf in all matters. Smith's timely leadership produced results--as long as he was present within the fort. In short order, lodging was provided for all, Smith neglecting any for himself. Procuring of such provisions as was possible from neighboring tribal villages, Smith set a strong example for doing 'business only' with the surrounding tribes. This was respected by the Powhatans, and what efforts he made bolstered the colony and provided much needed relief. Smith sought to resume his journeys of exploration at such times a the colony seemed doing well for itself. However, his absences left weak and selfish leaders in charge to work their worst, and this cost much energy to be wasted on unproductive projects--not the last of which was the result of a hunger for gold.

The Indians loved copper for its shiny luster. Pre-contact copper came largely

from the regions around the Great Lakes--dredged from the earth by glaciers

thousands of years earlier, raw, nearly pure copper nuggets were used by Great

Lakes Indians Indians for several thousands of years, and was traded widely,

though it remained scarce--and valuable--to the Indians everywhere outside of

the source-region. Copper artifacts are found across the southeastern and

midwestern United States, indicating the extent of trade and demands for it

Smith came not to make friends, but to secure the survival of the colony. In return, he offered the Indians 'such trash' as he called it, that presented the Indians with the opportunity to become quite trade-wealthy among their own and neighboring peoples. Trade hatchets, iron scissors, knives, brass hawk-bells, colorful beads, mirrors, copper kettles, iron sewing needles, brass thimbles, and various other items comprised the trade-goods offered by the english. Indians who frequented the fort also took what tools they found unattended, and many colonists as well as sailors secretely traded tools to the Indians for such food as they could obtain for them, depleting their own supply of much-needed equipment.

The utility and the beauty of the colonists' articles carried to virginia for

trading purposes did not escape the Powhatans. The ships' crews so wontonly traded

such behind the council's eyes that within a short few years the copper and

many other trade goods had lost their value almost completely. The Kiskiak

tribes' village-site, located on the now the Yorktown Navel Weapons Station,

revealed considerable numbers of copper oranments and pendants in refuse

heaps, indicating their sharp decline in value to the Indians

Ratcliffe and Martin, scheming to escape under cover of provisioning a pinnace for trade with the Indians, sought to abandon the colony for England; Smith, returning unexpectedly from exploring and trade, forced them to stay or sink by musket and cannon shot. Kendall was executed at this juncture, his hand in this event and of informing for the Spanish coming at last to a head. Ratcliffe and Captain Archer once more schemed to abandon the settlement, again to be suppressed by Smith.

Explorations up the Chicahominy River, a tributary of the James, and subsequent trading efforts with Indians dwelling there, provisioned the colony very well. Taken in abundance from the rivers were swans, geese, ducks and cranes. The colony feasted well upon the plenty of Indian corn, Virginia peas, pumpkins and persimmons, fish, fowl and diverse sorts of wild beasts. Such was Smith's abilities to provide for the common good that none sought to abandon the fort during this time of plenty. Smith continued to explore and map the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, encountering Powhatan Indians in every corner of his journeys.

Whispers and mutterings against Smith persisting yet. Censured for his failure yet to discover the headwaters of the Chicahominy, Smith set forth again, plunging yet deeper into the wilds with seven men aboard a barge. Finding, eventually no further passage for the barge, Smith and two men went forward by canoe, Smith warning the remaining 5 to stay aboard the barge and not to leave it for any reason...While Smith was gone, they went ashore where Indians attacked and killed them all. One of those killed at the barge was subjected to horrible tortures before he died.

Smith and an Indian guide, leaving the canoe and his two men with orders to stay put, entered a dark, marshy lowland beyond where no canoe could go. Shouts from yet unseen foes echoed through the wooded marsh, and Smith bound his guide to him as a human shield against the expected flights of arrows. Quickly overwhelmed, he fought fiercely and took several Indians down before, mired to his waste in a bog, he surrendered; his men in the canoe were both killed.

Captured!

Facing imminent death at the hands of hostile indians, Smith nonetheless

persuaded, cajoled and bluffed his way out of an execution by Opechancanough

and perhaps others whom sought to stem the English invasion of their homelands.

Smith was bound and brought before Opechancanough, Chief Wahunsenaca's brother. Calmly pulling his compass forth and demonstrating its working to the indians holding him--while he amazed his onlookers, his life still hung in the balance... Smith's captors thereupon bound him to a nearby tree and were prepared to loose a flurry of arrows upon him there, when Opechancanough stepped in to halt the killing. Smith's language skills no doubt played a role in his survival. Smith was moved from one village to the next, traversing nearly the length and breadth of the Powhatan Confederacy's lands. His friendship with his captors grew during this time, and his treatment was by his own accounts decent enough considering his predicament.

A compass such as Captain John Smith tried to mystify the Indians with,

hoping to induce enough wonderment and perhaps even fear, that he would be

released--it worked only in inducing wonder...Smith remained captive

Captain John Smith's travels as a captive, unknowing if death be but a moment

away at any given time, was often feasted and was able to mingle more or less

within Powhatan society. Smith learned much that benefited the colomy both in

later dealings and confrontations with the Powhatan Indians. His language-

skills advanced rapidly during his tenure with the indians, and little could

later be said but that he did not understand it quite well.

At one village, a shaman accoutered in stuffed weasel and snake skins, and darkly painted, skipped and danced around the fire before Smith. Followed were three days of feasting and drinking, Smith using all his skills to learn what he could of the land and waters around each village he was taken. Eventually being transported to Wahunsenaca's village of Werowocomoco, Wahunsenaca and his shamans qustioned Smith, devining by their mystical powers and contemplating his efforts to pursuade the Powhatans that he and the English had been forced ashore at Jamestown by the Spanish, and they were then endevoring to revenge themselves of a previous attack by the Powhatans' deadly enemies the Monacans, who dwelt beyond the Powhatan's realm.

The advantages of trade were felt by both sides--the colony survived a little

while longer each time food and provisions were acquired, and the powhatans

grew wealthy in their own ways with materials and goods that outlasted their

own more primitive tools, outshown their more common ornaments and symbolic

items of higher status--and trade with outlying regions and other tribes

beyond Powhatan borders carried with it the ability to establish and maintain

more peaceful relations with their enemies--trade-profits brought stabalizing

peace as opposed to conflict and war

Whether Wahunsenaca believed Smith or not, he offered to supply the colony with such food and provisions as they might need, as wellas his protection, IF the english would relocate themselves to a place just downrivewr of Werowocomoco AND acknowledge him as their ruler. Smith would not agree to this proposal, and rejected yet another whereby he would have assumed the role and position as a local werowance or chief, with the requisite benefits of land, possessions and women. What folowed was indeed a strange ceremony--one that has caused much speculation and debate ever since...

Scholars and historians tend to disagree somewhat on the meaning of, and even the actual events, of what followed: Smith was dragged to a place before two large stones, his head forced upon one as a warrior approached with upraised club, obviously intent upon taking his life. A the crucial moment whereby Smith would have been killed with a crushing blow to his skull, the young maiden Pocahontas, Chief Wahunsenaca's favorite daughter, brushed past the onlookers, and imposing herself between the club-bearing warrior and Smith, pleaded for his life.

From the movie "The New World", 'Captain John Smith' is saved from execution by

'Pocahontas', then a young girl of perhaps 11 or 12 years old. Thought by

many scholars to have been an elaborate adoption ceremony where Smith's life

was 'saved' as a demonstration of his rebirth into Powhatan society. Among

the Algonqiin Tribes of the eastern United States, such adoptions were common,

and those who had lost family members in conflicts could replace them with a

claim upon a condemned prisoner. It was likely that Wahunsenaca hoped Smith would

recognize his responsibilities to and never turn against his Powhatan brethren.

The two recognized each other as equals, Wahunsenaca calling Smith his 'brother'

and, Pocahontas refering to him as 'father', thus setting the stage for

much hoped for peaceful relations bewteen the two cultures

Smith was soon released from his captivity, sent back with the express promise to return with two of the colonists' big guns and one of the english grindstones. Smith probably laughed inwardly as he considered the deal he'd made. Turning over to the Indian porters accompanying him back the two cannons, demiculverins each weighing some two tons each, in a rare instance of understaement, Smith observed the Indians found them "somewhat too heavy". demonstrating their power as weapons by firing one at an ice-covered tree, the resulting explosion sent the Indians scattering for home. Smith recalled them and gave to them, and for Wahunsenaca and his women, such trinkets as seemed to make them quite happy for it all.

Upon settling back into fort-afairs, Smith was accused of having lost all his men, and senteneced to death for his 'crimes'. Smith, having somewhat more clout among the colonists than before, and due to his successes with trading for food and his expert handling of the works needed to secure the conditions of colony, was able to successfully rebuke his accusers without further censure. Captian Christopher Newport made his return to Jamestown at this juncture as well, and those factions seeking Smith's death abandoned all effort to further their schemes against him.

Newport left the colony in good condition the previous summer. seeing upon his return, in seeming punishment for their greed and gold-seeking misadventures, starvation and disease had taken a dire toll upon the colonists numbers. Of 105 colonists in Jamestown the previous summer, but 38 remained alive. Newport's resupply ships' new arrivals, bolstered by his positive outlook on the colony's stature, were shocked to see the dspairaging circumstances awaiting them in Jamestown. nearly two thirds of the colony had perished, the council president had been deposed, another had been shot, and Smith was sentenced to hang... No gold or other precious goods were discovered, and the colonists strongly favored immediate abandonment of the colony.

Powhatan Indians perceived their places of habitation as having been ordained

by their Creator, who placed them where they should live. A key point in this

understanding is the lands they dwelled upon were also the lands where their

forefathers lay buried-sacred ground to the Powhatans. As such, to be forced

to give ground before the English was deeply upsetting to their way of life,

their traditions of worship, and their very survival

Newport and Smith realized somethinng had to be done--the overall mismanagement of affairs in the hands of weak and self-interested leaders had nearly destroyed the colony. Smith was the only natural leader among them all, and with his intimate understandings of the layout of the and, experiences in dealing with the Powhatans and his fierce dedication to producing positive results for the colony's benefits, at his own expense in comforts and compensations, his stock rose sharply among the colonists. The provisions Newport carried, along with incresing the numbers of able-bodied men and specialized craftsmen served as a steadying bulwark against the colony's impending dissolution. Christopher Newport was recognized by the Powhatans as a leader of some power, while Smith was without doubt the most respected and to-be-feared warrior-leader of the colony. Overall, the Powhatans preferd to deal with Smith.

Captains Newport and Smith, with 40 men set off to see Powhatan at his village on the York River--while this was only 20 miles as the eagle flies, the journey had to be undetaken by boat, as a vast swampy wilderness lay between Jamestown and Werowocomoco....and the York would still have to be crossed. Upon arriving, Newport kept to the shore while Smith and half the men as armed escorts proceeded into the village. Hundreds of villagers in their best fashion turned out to greet the Englishmen, and Wahunsenaca made note that Smith still owed him the guns and grindstone, though laughed at the predicament his men found themselves in at Smith's relation of events. Send me something of less burden, was his reply.

Wahunsenaca offered that Smith's men should lay down their arms, whereat Smith replid that such a request was a ceremony our enemies desire, but never our friends! Smith was not to be out maneuverd in the making of a deal here--Powhatan food and provisions must be had for the colony to thrive. An exchange of young men was then arranged--each providing one of their own to each so that both may know of the others' sincerity in their dealings. Wahunsenaca thus declared that all the settlers were now members of the Powhatan community. (later, Smiths adversaries amng the colony claimed he conspired to set himself up a kingdom and rule with Wahunsenaca and the Powhatans as his ally).

Trading began the following day with Wahunsenaca's demands that Newport put all that he'd brought with him out upon the ground so that he might more fully appraise it all at once. Newport, seeking to establish his own position with both the colonists and the Powhatans--and against John Smith's greatest cautions not to do so, complied. Newport rasoned that a quick sale would be diplomatically advantageous, that open and friendly trading would set a precident for future relations. Smith took a longer view of these proceedings and sought to maintain a firm hand in dealing with the Indians.

Trade with the Powhatans meant survival--dealing with the Powhatans to

acquire much-needed provisions was not always a simple matter. Smith's

extensive dealings, captivity among and knowledge of the Powhatan indians,

and his alrady extensive linguistic abilities enabled the colony to survive

through his efforts with the Powhatans. His successes were not always met

with open appreciation among the English--factions seeking to pull Smith

down conspired with intrigues against him, while thriving upon the very

provisions his successful dealings with the Powhatans provided them.

Captain Christopher Newport, an experienced sailor and leader of great courage,

was responsible for the resupply efforts of Jamestown, also carrying with him

in each return-journey more settlers to bolster the colony's dwindling numbers

during its earliest years. At one time a privateer carrying letters of mark--

in effect a license from Queen Elizabith I to plunder Spain'streasure-

galleons coming from her colonies in New Spain, Newport brought home to England

a treasure of gold and precious stones, including a 500-place table-

setting

bearing Spains' Kings' roayl coat-of-arms. Zunega, Spanish ambassador

to

England, was invited upon Newport's return, to dine in celebration of his

victory--from the very same solid gold settings Newport had captured!

Wahunsenaca, at seeing in full all the goods brought to the table, kept his delight hidden, and declaring the amassed goods to be of little worth to him, offered a mere few bushels of corn for the lot, gaining all by outmaneuvering Newport's intentions. Disparaging of Newports' efforts in silence, Smith idly toyed with a few strands of deep blue beads hanging inconspiciously from his pocket--and Wahunsenaca did not fail to notice! Informing Wahunsenaca that the beads he held were treasures fit only for kings, that none other but the crowned heads of Europe might possess these... In contrast with Newport's dubious success, Smith elicited such a wealth of provisions as to nearly overlaod the shallops he and his men sailed in.

Such successes with trading delivered the colony from disaster, yet disaster of another nature loomed over the burgeoning colony, one that would threaten all and everything in its complications. Fire sprung up and swept through the settlement, destroying the storehouse, homes, the church and kitchen...most of the supplies and provisions Smith had obtained by his wise dealings with the Powhatans were utterly lost... The colony was thus forced to depend upon the Indians mercies for their survival. Wahunsenaca's beloved daughter, Pocahontas, was by now close friends with Smith, and through her efforts the colony continued to benefit from the Powhatan's mercies in the form of food, sometimes brought under strictest secrecy from her fathers' knowledge.

While the Powhatan Indians often refused to trade or otherwise supply the

colony, Pocahntas, often in secret came with food, while those escorting

here were suggested by some to be gathering information about the colony's

growth and prospects of survival. Wahunsenaca may have been aware of these

enterprises and sought such information as could be used to the Powhatan's

benefit. A legend was born of these efforts, one that holds people enthralled

to this very day--America's first successful colony succeeded in part by her

generous kindness stemming from her deep friendship with Captain John Smith

The exteneded stay of Newport and his ship caused some grief as well--much of what the ship had brought and Smith's trading secured in the way of provisions were thus eaten up in part by the ships' crew, leaving but little once fire had done its work. Wealth and riches still loomed large in the hearts and minds of many, for with Newport's arrival came two refiners and two goldsmiths, whose deplorable enthusiasms caused much excitement and effort digging for gold rather than securing food, rebuilding homes and production of useful commodities. Burdened with so-called 'ore'--the primary product of the colony's industry in spite of Smith's hard efforts to elicit more productive activities--Newport's ship and crew departed in April for England.

Trouble was soon brewing between the coloniest and the Powhatans--thieves frequently stole tools and other items belonging to the colony, and when two of them were aprehended, it was learned an ambush was being planned--to attack Newport upon his retuen and to assault the fort therafter. Whether this was in fact the intentions of the Powhatan Indians or not, it served to underscore the colony's need to become self-sufficient--quickly and permanently. During this time, Pocahontas continued to bring much-needed supplies--and word from her father of his apologies for any misuse his people had delivered upon the colonists. With further plans for gold-hunting explorations dismissed as wasteful and put down, Smith soon embarked upon another journey of exploration along the eastern shore's western coast.

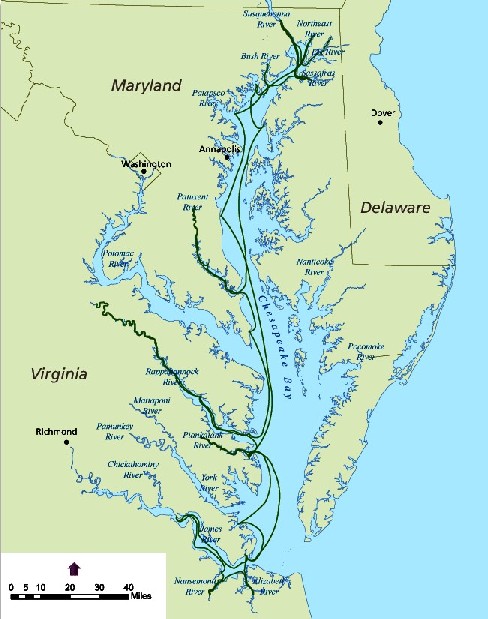

Through numerous explorations, Smith mapped out the Chesapeake bay region with

incredible accuracy while acquiring more vital information: head-counts of

warriors at each village and hamlet along the way provided intelligence about

Powhatan strengths and weaknesses. Encountering warring and peaceful Indians

alike also underscored the fact taht Wahunsenaca was not absolute in his rule

over the loose confederation of tribes he held dominion over. More distant

tribes were prone to acting more solely upon their own interests than in

following dictates from Werowocomoco

Smith's explorations of the Chesapeake Bay gained him valuable knowledge on several fronts: initial contacts were ambiguous to thratening, but quickly became quite friendly, and the creeks, harbors and other geographical features were made due note of. A werowance named Kiptopeke informed the explorers of disease which had mysteriously taken the lives of most of a village, and Smith was appraised of information which he then supposed might led to a possible avenue to the orient, and of distant peoples who were traded with for the fine furs and other goods Smith thought could prove valuable to colonial interests. The Nanticoke tribesmen offered violent confrontation at first, but later turned about and Smith was impressed by their forthright and honest trade dealings. Storms encountered caused much concern and at one point their vessel's mast and sails were badly damaged. Fresh water became scare and the crew pleaded for their swift return. Smith, ever the competant leader, cajoled them all to enduring things longer, and fotune seems to have smiled upon them for the most part thereafter. Encounters with many peoples led at times to conflict, misunderstandongs and openly welcomed trade. Smith put his good senses to use and learned much of the political structuring of the Powhatan Confederacy in these more distant realms under Wahunsenaca's dominion, including the fact that distances tended to mitigate the Werowances' influence.

Click on Smith's map to view a zoomable version in much greater detail

A comparison of these two maps will show the accuracy Smith achieved in

his explorations and mapping efforts. The map at right marks the paths of,

exploration Smith and his crew took on this, Smith's first Chesapeake bay

exploration. Hundreds of place-names first used by Smith in his maps

are still in use throughout Virginia today!

One source of interest sprang from the assayers' analysis of some of the glittery dirt taken back to England--silver was reported to be found in it! The werowance of the Patawomecks offered that such was called matchqueon--a silvery substance warriors applied to their skins with grease. The Indians themselves marketed this substance far and wide, washing it out of the soil and placing it in little leather pouches. Smith ws given guides and, chaining them together that they might not turn upon them, were gladdened to learn they could keep the same chains binding them upon the jurney's completion. The mine was well inland and proved to be all that was said of it by the werowance himself. As it turns out, the substance was probably antimony, a silvery-white crystaline substance now used in alloys and semiconductors. Fish were caught by skewering them upon their swords, and an abundance of wildlife and fowls of every kind were found, marking this territory a richly stocked land. At one point, miscalculating himself, Smith suffered injury from a stingray's tail-barb, yet his vitality and inner strength keeping him from greater harm. The crew made haste in their return to Jamestown and the surgeon there.

As Opechancanough's prisoner, Smith had visited several tribes and made friends among them. He noted the Rappahannock River to be large enough to warrant further exploration, and he wished to seek out those peoples he had previously been aquainted with from his weeks as a captive. The Rappahannock would have to await another journey of exploration, though, as Smith's injuries might still have prove lethal. Arriving quickly at the mouth of the James River,and loaded as they were with the numerous shields, arrows and weapons traded them or acquired when enemies launched unsuccessful attacks, Smith's bravado turned to entertaining a few Kecoughtan Indians they met with tales of having come back victorious in battles with their dread enemies, the Massawomecks. Word of Smith's accomplishments spread quickly throughout the region and added much to his already fierce reputation as a warrior. In yet further entertainment, Smith's vessel was decked out with such streamers and shields, etc to ressemble a Spanish frigate--materials carried just in case an actual Spanish ship might have been encountered. No record of the colony's reaction is made of this ruse, and no one fired upon Smith and his men as they returned to Jamestown.

Smith's return probably saved Ratcliffe's life--n his absence, Ratcliffe had in Smiths' estimation, reduced the colony to inability "to do anyhting but complain of the pride and unreasonable needless cruelty of the silly president that had riotously consumed the store. And to fulfill his follies about building him an unnessessary building for his pleasure in the woods, had brought them all to that misery had we not arrivd they had as strangely tormented him with revenge". Smith was asked to assume the office of president of the council, yet he declined and instead prepared for yet another journey of exploration--intending to follow up with discovery of the nature of the Rappahannock River's origins. Arm-chair geographers back in Europe emphatically beleived that China and the passage thereto were but close at hand to the American coast. Master Scrivener, who had made record of the majority of Smith's previous journey of discovery on the bay, was aided by more noble gentlemen of character to enforce the duties of the office he declined. Ratcliffe was deposed in shame of his failures at leading the colony, his personal stores skimmed from the common kettle dispersed among the rest. Leaving the colony to rest and regain its health, Smith set off yet again, being in Jamestown but a mere two weeks.

Captain John Smith's reputation spread before him like a wind, and th Indians of the region knew all to well of his prowess--a fact that Wahunsenaca did not misinterpret. Perceiving Smith to be much like himself--a warrior and leader of great capability and bravry as well, Wahunsenaca held Smith in high regard as both an aversary and an equal. The growing knowledge that as a redoubtable leader and warrior, Smith stood at the fore of English settlement and further colonization of the lands his people occupied, a force to be reckoned with, was a concern he must eventually deal with in terms profitable to his peoples' survival...

Making swift journey towards the upper rachs of the Chesapeake Bay, tides and favoring winds supporting them as the traveled northward, Smith and his men encountered the Masawomecks, seeming at first friendly, an ambush was yet discerned to be plotted against them as flights of arrows descended upon the vessel, but to no effect. Several of his men had taken ill, and Smith's expedition was upon this circumstance short-handed of able-bodied men to stave off any concerted attacks. By bluff and subterfuge, Smiths' vessel (smartly adorned with the same shields and accutrements that so impressed the Kecoughtan Indians of his warring abilities) also adding numerous hats between the shields displayed, quickly charged them under full sail! They, seeing this as insurmountable to their means, took flight. Sailing to the very beach they'ed fled, Smith anchored and at length induced a few to come aboard, where at last many did so, carrying to Smith many signs of friendship in the quantities of venison and meats, arrows and clubs and the like as gifts. Appointing them to meet again in the morning, yet they did not show up and Smith was left to carry forward his explorations.

Massawomeck arrows fly as Smith and his men, most of whom are ill and unable to fight,

protect their vessel with Indian shields, both to ward off this assault and to portray

themselves better-manned and equipped to fight off the assault. By Smith's quick

thinking and prearations, his ne instead so impress these Indians as to win their

friendship and cooperation to meet the Susquehannocks, their mortal enemies...

Entering the Tocowogh River, about them swarmed a fleet of canoes of armed Indians, and the Massawomecks, perceiving the numbers of Massawomeck shields and arrows aboard, accepted Smith's bluff they were taken in combat. Seeking peaceful relations and not war, parley was arranged, entering their village these savages expressed their best abilities to be friendly, many gifts and accomadations being made. smith inquired of the iron and brass, hatchets and other eurpoean goods they possessed, being informed they were obtained from the Susquehannocks, their mortal enemies, who dwelt two days' journey beyond the rocks past which Smith's vessel cound not pass. Prevailing upon his interpretor to engage yet another interpretor, for the Susquehannocks' language was not the same as the Powhatans', to go among the Susquehannocks and interest them to come visit Smith and his men, they did so, expecting to return in three or four days' time. meanwhile Smith and his nen enjoyed their stay among these massawomecks, their food and civil treatment of them welcomed after the sickness most had endured during this foray up the Chesapeake Bay.

The Susquehannock were recorded by Smith to be giant-like and quite inordinately

large of physical build (the average height of eurpoeans at this time was around 5'-5")

As an added footnote this this, reports of 8' tall Indian skeletons abounded for some

years--as uncovered where they lay, their bones portrayed giant proportions; later

archaeological work revealed the truth--while the Susquehannocks were indeed taller

than the english, such seeming proportions are misleading. Archaeological drift,

the natural movement of artifacts and bones within the soil over hundreds or

thousands of years, as well as the natural processes of skeletal disarticlation

after

death, seperated the bones enough to suggest more gigantic proportions

than in actual life--American history is filled with such uneducated assumptions .

The Susquehannocks, some 60 of them, giant-like, came to Smith bearing all manner of gifts: venison, baskets, shields and bows, and tobacco pipes three feet in length. Among them were five of their chief werowances, who came aboard Smith's vessel, leaving behind their men and canoes. Smith and his men daily engaged in their prayers with psalm, and the Susquehannocks, so impressed by their solemnity, took to their own prayers and much embraced Smith, covering him with a great painted bear-skin, avowing their great love for him. They did so honor Smith and his men with more, some 18 other hides and great strings of shell beads, proclaiming him their protector and promised all aid and provisions for them, if he would but stay among them to avenge them of the Massawomecks. Smith found himself a significant figure in the relations between their two tribes, a power that both sought to honor and covet unto themselves. Smith gained knowledge of more distant tribes, and from where the iron, brass and copper goods they possessed had come--apparently these arrived via trade with tribes living along the Great Lakes region far north of Virginia, whom in turn obtained them from the French.

A village of the Susquehannocks. Smith reports these peoples to be using birchbark

for their canoes, their being much lighter than those of hollowed logs used by the Powhatan.

From these Indians, too, came the fine furs Smith and his men had seen previously,

in

the hands of the Nanticoke Indians of the Eastern Shore, whom the Susquehannocks

bartered and traded with when it suited them.

Smith and his men left notes in tree-holes, brass crosses nailed upon tree-trunks and they raised wooden crosses to proclaim "Englishmen have been Here!" Smith and crew turned southward again, entering the Rappahannock and finding accomadations among the indians dwelling at a village called Moraughtacund. An old aquaintence of Smiths, one 'Mosco' a 'lusty savage of Wighcocomoco up the river of Patawomeck, and supposedly of French descent on account of his bushy, thick beard, the savages seldom having any at all.' Mosco proved an able and dedicated guide and servant to Smiths' needs as ever there was, enlisting his fellow countrymen to tow against wind and tide smith's vessel until they arrived by such means to Patawomeck, the village of the Rappahannocks, even against Mosco's advice to Smith, for the Rappahannocks were intent on a fight. There, Smith played Solomon in such manner as to prevent an outbreak of hostilities among the indians of Massawomeck and Rappahannock, settling a dispute over stolen wives and offended pride.

Another Black Mark Upon Indian-Colonial Relations

In an event wherby King James had sent orders that Wahunsenaca be 'crowned'

by Captains Smith and Newport, Smith worked to avoid doing so, knowing that

as a king himself, Wahunsenaca would not subordinate himself to any other king,

least of all one residing across the ocean and far from his own lands. Newport

eventually forced Wahunsenaca to bow under physical pressure to receive the

cheap copper crown, as yet one more event was added to a growing disaffection

between the Powhatans and the English. Such blindness to colonial-Indian

realities back in England often provoked anger and dangerous situations

that threatened the colony's survival

A desperate fight between Smith and Opechancanough, Chief Wahunsenaca's fierce

brother and chief of the Pamunkey tribe, ended with Opechancanough giving

ground and avowing his people's friendship, although his hatred for

Smith

and the English burned deeply inside him, later flairing into the

widespread

massacre of colonists in 1622, and again in 1644, when Opechancanough

was in

his 90's. This redoubtable chief was killed during the final massacre,

which

had but little effect upon a colony numbering thousands and growing

almost monthly with new arrivals

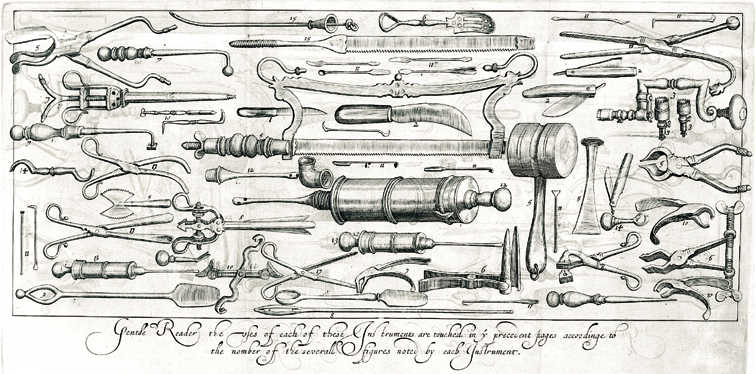

Evidence discovered during the Jamestown Rediscovery projects' excavations

under Dr William M. Kelso demonstrate that the surgeon accomapnying the

colonists was equipped with at least some of the instruments shown here.

Medicine and surgery were chancy in this time-period, medicines themselves

being more based upon superstitious belief than proven effectiveness

All material is copyrighted by David Stone Sweet, 2008-2009,

and may not be reproduced in any form without express written consent.

Stone’s Educational Archaeology Links

The Golden Age of Exploration and the Settlement of Virginia

Virginia's First Peoples:

A FREE Hands-On Cultural Materials Lecture

Program for Schools, Civic groups, Scouting and Others

Clovis and before:

The First Arrivals to America

Stone's Archaeology Pages

What IS Archaeology?

Email: stone@crosslink.net

|