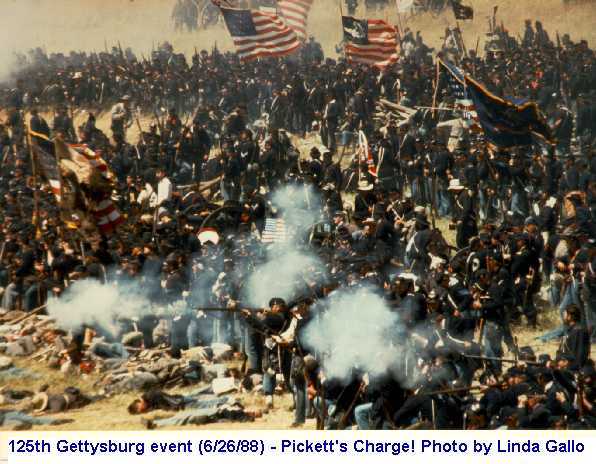

Pickett's Charge

Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of

Chickamauga

Battle of

Chickamauga

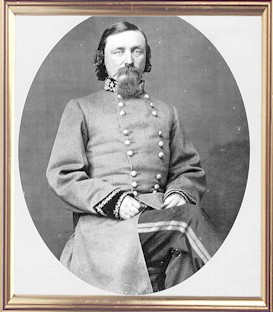

George Edward Pickett

1825-1875

![]()

It was at one o'clock that two

Confederate signal guns were fired, and at once there opened such an artillery

combat as the armies had never before seen. As a spectacle, the fire from the

two miles of Confederate batteries, stretching from the town of Gettysburg

southward, was appalling; but practically the Confederate fire was too high, and

most of the damage was done behind the ridge on which the Army of the Potomac

was posted, although the damage along the ridge was also great. The little house

just over the crest where Meade had his headquarters, and to which he had gone

from Gibbon's luncheon, was torn with shot and shell. The army commander stood

in the open doorway as a cannon shot, almost grazing his legs, buried itself in

a box standing on the portico by the door. There were two small rooms on the

ground floor of the house, and in the room where Meade had met his corps

commanders the night before were a bed in the corner, a small pine table in the

center, upon it a wooden pail of water, a tin drinking cup, and the remains of a

melted tallow candle held upright by its own grease, that had served to light

the proceedings of last night's council of war. One Confederate shell bust in

the yard among the horses tied to the fence; nearly a score of dead horses lay

along this fence, close to the house. One shell tore up the steps of the house;

one carried away the supports of the portico; one went through the door, and

another through the garret. It was impossible for aids to report or for orders

to be given from the center of so much noise and confusion, and the little house

was abandoned as a headquarters, to be turned, after the firing was over, into a

hospital.

During the cannonade the infantry of Meade's army lay upon the ground

behind the crest. By General Hunt's direction the Union artillery fire, with the

exception of that of the Second Corps batteries, was reserved for a quarter of

an hour and then concentrated upon the most destructive batteries of the foe.

After half an hour both Meade and his chief of artillery started messengers

along the line to stop the firing, with the idea of reserving the ammunition for

the infantry assault, which they well knew would soon be made. On the other

side, Alexander sent word to Pickett to come quickly, and the Confederate

assault began.

Crossing the depression of the ground, a part of the Confederate line,

after emerging from the woods, found a moment's rest and shelter, and then

started toward the little umbrella-shaped clump of trees on the Union line, said

to have been pointed out by Lee as the objective of the assault. On the left

Pettigrew's division of four brigades advanced in one line, with Trimble's two

brigades of Lane and Scales in the rear and right as supports. Pickett's

division on the right advanced with the brigades of Kemper and Garnett in the

front line and Armistead's brigade in rear of Garnett's on the left. Twenty

minutes afterward the brigades of Wilcox and Perry were to advance on Pickett's

right and repel any attempted flanking movement. The assault was made by

eighteen thousand men. To cover the advance the Confederate artillery reopened,

and when the infantry line appeared the Union guns were directed upon the ranks.

Great volumes of smoke, however, soon obscured the field, and many of the

Confederates could not see that there was a foe in front of them until they were

within two hundred yards of the Union line. Under the artillery fire from

McGilvery and Rittenhouse on Pickett's right his part of line drifted to the

left, and thus, when the brigades of Wilcox and Perry marched straight ahead, as

ordered, for the purpose of protecting Pickett's right flank, their course took

them to far to the south to accomplish their purpose, even if the advanced line

by that time had not gone into pieces. As Pettigrew had formed behind Seminary

Ridge, his troops had to advance under fire a distance of at least thirteen

hundred yards, while Pickett's place of formation was but nine hundred yards

distant from the objective point. The start was made in echelon, with Pettigrew

in the rear; but by the time the Emmitsburg road was reached both divisions were

on a line, and they crossed the road together. Brockenbrough's Virginians,

Pettigrew's left brigade, were disheartened by the flank fire of Hays' troops

and Woodruff's battery after a loss of only twenty-five killed, and these troops

either retreated, surrendered, or threw themselves on the he ground for

protection; but the other brigades of Pettigrew, as well as those of Trimble,

advanced to the stone wall, stayed there as long as any other Confederate

troops, and surrendered many fewer men than did Pickett.

The drifting of Pickett's division to the left exposed the flank of his

right brigade (Kemper) to the fire of Doubleday's division, a part of which

moved with Pickett, thus continuing its deadly volleys, while Stannard's brigade

by Hancock's orders, changed front to the right, and opened a most destructive

fire upon Kemper's flank. Armistead's brigade moved in between Kemper and

Garnett, and together they marched upon the angle of the stone wall held by

Webb's Philadelphia brigade, Garnett, just before death, calling out to Colonel

Frye, commanding Archer's brigade of Pettigrew's division on his left, "I am

dressing on you." Scales' brigade, whose commander, Colonel Lowrance, says it

"had advanced over a wide, hot, and already crimson plain," and through whose

ranks troops from the front began to rush to the rear before he had advanced two

thirds of the way, together with Lane's brigade, advanced to the front line,

Lowrance's brigade reaching the wall. The two guns of Cushing's battery at the

wall were silenced. The greater part of the Seventy-first Pennsylvania Regiment

of webb's brigade had been withdrawn from the wall to make room for the

artillery, and the two remaining companies, overwhelmed by the mass of the enemy

concentrated at this point, were driven back from one hundred to one hundred and

fifty feet. Through this gap the Confederates crossed the wall, and Armistead,

putting his hat on his sword, dashed toward the other guns of Cushing's batter,

near the clump of trees, and fell dead by the side of Cushing. The Sixty-ninth

Pennsylvania of Webb's brigade held its left flanks by the enemy. The

Seventy-second Pennsylvania and two companies of the One Hundred and Sixth

Pennsylvania advanced to the wall; Cowan's New York battery galloped up; Hall's

brigade of Hancock's corps, by the orders of Hancock, on Webb's left, changed

front, and poured its fire into the Confederates' flank; Harrow's brigade also

attacked Pickett in flank. The attack of Pettigrew and Trimble, farther to the

Union right, fell upon Hays' division of the Second Corps. The Eighth Ohio

changed front, facing south, reversing the tactics of Hall's brigade on the left

and opened a flank fire. General Pickett, in person, did not cross the

Emmitsburg road. Of his three brigade commanders, Garnett and Armistead were

killed, and within twenty-five paces of the stone wall Kemper was wounded and

captured. Pettigrew and Trimble and three of their brigade commanders (Frye,

Marshall, and Lowrance) were wounded. The brigades of Wilcox and Perry, exposed

to a heavy artillery fire from the fresh batteries moved to Gibbon's front

again, and, seeing the repulse of the assault to their left, fell back to the

main Confederate line.(break) Out of the fifty-five hundred men which Pickett

took into action, fourteen hundred and ninety-nine surrendered, two hundred and

twenty-four were killed, and eleven hundred and forty were reported wounded.

Pickett lost twelve out of fifteen battle flags. Pettigrew's division, in which

there was one brigade of North Carolina troops , lost in killed and wounded

eight hundred and seventy-four, and in missing five hundred. Trimble's two North

Carolina brigades lost in killed and wounded three hundred and eighty-nine, and

in missing two hundred and sixty-one. The two brigades of Perry and Wilcox

together lost three hundred and fifty-nine. Pettigrew's brigade of North

Carolina regiments, commanded by Colonel Marshall, lost in the charge five

hundred and twenty-eight, of which number three hundred were killed and wounded;

and the Twenty-sixth North Carolina of this brigade, which regiment suffered

greater losses during the war than any other on either side of the conflict,

went into this charge with two hundred and sixteen men, and returned with but

eighty-four. The percentage of losses in killed and wounded in the assaulting

column, taken as a whole, was not extraordinary for the civil war. The place

assaulted was less formidable than Fort Fisher, which was taken later in the war

by Union troops, and the assault itself was far less successful than that of

Meade's division at Fredericksburg. Its complete failure was due to the thorough

dispositions made to meet it, and it is improbable that the result would have

been reversed if McLaws and Hood , whose attention was occupied by the

appearance of the Union cavalry on their right, had participated in the assault.

The tactical skill which had prevented the rout of the Third Corps from

involving the whole army in a defeat on the second day of the battle, was

exerted with equal success in supporting the center under attack on the third

day.

At the center of Meade's position, were troops rank after rank, infantry

division after division, line upon line, including even the provost guards, and,

in rear of all, a regiment of cavalry waiting to shoot down the craven if he

would discover himself. Against an army so disposed, in such a position, and so

handled, its different parts thrown from point to point with certainty and

promptitude, with every possible Confederate movement anticipated and provided

for, the assault ordered by Lee was in truth the mad and reckless movement that

Meade characterized it, and it accomplished no more than a slight fraying of the

edge of the front Union line of troops.

On the Union side, Hancock, Gibbon, and Webb were wounded and carried

from the field. The union losses were twenty-three hundred and thirty-two.

Webb's brigade losing more than any other. One hundred and fifty-eight artillery

men were killed or wounded. Before the attack Meade had told Hancock that if Lee

attacked the Second Corps position he intended to put the Fifth and Sixth Corps

on the enemy's flank. Recalling this remark of the army commander, Hancock,

while lying on the ground wounded, dictated a note to Meade, expressing his

belief that if the movement contemplated by the army commander were carried out

a great success would be won. The Sixth corps, however, was not now a compact

organization, its different parts, having been disposed in different portions of

the field. The Fifth Corps was ordered to carry out the contemplated movement,

but it had also been moved to support the center. There is a limit to human

endurance, and the slowness with which the movement ordered by Meade was made,

owing partly to the difficulty of collecting the troops, was no doubt largely

due to sheer exhaustion caused by the supreme efforts which had now been

prolonged for six midsummer days.