Selection stage 2

CONTINUATION TRAINING

The survivors are then sent for continuation training, during which

they are still being tested for their suitability as SAS soldiers.

The first thing is training in the weapons of the regiment. M16, 203,

Browning pistols, ETC.

Most soldiers will have never used these weapons before so it

essential that thay are skilled in there use.

They also need to be trained on Eastern bloc weapons, AK47`s, ETC.

A lot of the time sas soldiers will be required to use these weapons

rather than their own, especially if operating in a foreign country.

There is still a lot of physical work in the gym to keep the fitness

levels of candidates high.

Candidates are also tested for their mental abilities.

Language aptitude, arithmatic and english language are all tested, as

well as a series of mensa tests.

This is to check if a candidate has the basic aptitude to adjust and

learn to the sas way of doing things.

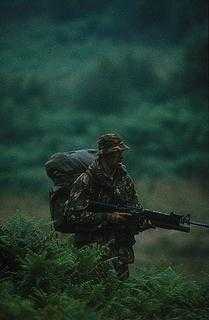

JUNGLE PHASE

Jungle training takes place in the British army jungle traning

school in Brunei.

It teaches the basic skils required to live in the jungle for weeks on

end, as well as how to navigate in the dense jungle.

This is one of the hardest for candidates to learn, because the jungle

is difficult to operate in.

It is easy to become lost in the featureless environment, with short

visibility no virtually no landmarks.

The candidates then move onto patrolling and contact drills.

This is done individually at first, moving on to patrols of 4-5 men.

COMBAT SURVIVAL PHASE

One of the most testing and controversial elements of con-

tinuation training is a three-week, combat-survival course at

Exmoor, in which candidates are stretched psychologically as

well as physically. The point of such training is to prepare men

to fight a guerrilla war behind enemy lines. Much of the course

is run by a Joint Services Interrogation Unit staffed by SAS and

other personnel. It is preceded by a special period of training at

the regiment's Hereford base. Both courses are a mixture of

tuition in living off the land -- identifying edible seaweed and

fungus, learning trapping techniques to procure game or fish

-- followed by a realistic application of these lessons, in which

the student spends several days and nights on the moor, being

hunted by soldiers from other regiments. Cunning candidates

have been known to pass some of this time comfortably as

unofficial guests of people living on or near the moor.

The Exmoor course contains the usual 'sickener' element.

Devices include a variant of the numbered brick, a five-gallon

jerrycan of water to be carried over long distances. To eliminate

the possibility of cheating, the water is dyed and the Jerrycan

checked by instructors.

At the regiment's Hereford base and, subsequently, on the

Exmoor course, SAS candidates are also subjected to interro-

gation of a kind that, to judge from the testimony of those who

have passed the course, does not differ from the treatment about

which terrorist suspects complained in Ulster in 1971, and which

was studied by the Compton Commission. Already-exhausted

soldiers have been subjected to physical hardship and sensory

deprivation, including the use of a hood placed over the head for

many hours, white noise and psychological torture. The object

of these techniques is to force the combat-survival students

to reveal the names of their regiments and details of the

operations on which they are nominally engaged. Not all those

participating are SAS candidates; Royal Marine Commandos

and Parachute Regiment soldiers also take part. The difference

is that for the SAS nominee to break is more than a chastening

experience: it means he has failed to win a place in the regiment.

Those who fail at this stage are often the men who seemed best

fitted to the physical rigours of the earlier selection process on

the Brecon Beacons.

The experience of one successful candidate in recent years

is that three periods of hooded interrogation occur during the

two interrogation-resistance courses: a half-hour 'nasty'; an

eight-hour period and finally, during the Joint Services' Exmoor

Course, one of twenty-four hours interrupted only for periods

of exposure to bright electric light while facing the interrogation

itself.

In one instance, hooded SAS candidates were hurled from

the back of a stationary lorry by their over-enthusiastic captors,

members of an infantry regiment, on to a concrete road as part of

the pre-interrogation, softening-up process. One man suffered

a broken arm as a result. A successful candidate on that course,

who was still intact, recalls that he then spent eight hours sitting

manacled in a puddle as a preliminary to questioning. During

another period of interrogation, he was hooded and shackled

to a strong-point in a room in which white noise and coloured,

flashing lights were used. After some time, guessing that he was

alone, he contrived to remove the hood and regain a sense of

reality. 'I looked around and there were all these flashing

lights',

he said later. 'It suddenly seemed ridiculous to me. But until then

it was a bit unnerving. Some people get frantic in there. I think

there is a limit to how long you can stand it. After 24 hours

you begin to wonder if they are on your side. At the time,

while it was happening, I was told that the `treatment` would

go on much longer and I was almost cracking.' At Hereford,

as both victim and interrogator, he took part in more refined

psychological brutality during a preliminary combat-survival

course run exclusively for the SAS. Candidates were tied to a

wooden board and immersed in a pond for up to twenty seconds

before being recovered to face the same questions: 'What did you

say your regiment was? What did you say you were doing?' One

who survived this test later told his interrogators that he realised

no one intended him to drown, but he did fear the possibility of

a miscalculation, or that things would simply get out of hand.

An SAS interrogator with 'a Machiavellian turn of mind'

so arranged matters that hooded captives thought they were

about to be attacked by 'a perfectly lovable Labrador'. In an

adjoining room, meanwhile, they could hear a beating taking

place followed by the sound of vomiting and running water.

The victim of the beating was an old mattress; the groans and

vomiting were simulated by the interrogation team. An even

more elaborate charade involved the use of a railway truck

in an old siding, part of a disused ordnance depot. 'We had

these guys handcuffed to the rails. By this time they were

disoriented and tired. What they heard was a voice shouting

from a distance, "Get those men off the line!" The other

guards

then went through a pantomine. "Bloody hell, there's a train

coming. Get the keys!" The prisoners could feel the vibration

of the truck approaching. As it got closer one of the guards

shouted, "It's too late. Jump!" In fact, the wagon

went past them

quite harmlessly on an adjoining line into the siding. Among

the prisoners, reactions differed. Some positioned their hands so

that the wagon wheels would cut the shackles and set them free.

Some got themselves into a position where they would have lost

an arm. Others went berserk and ended up lying across the rails.

But every one of them thought that this was a real emergency

and that we had made a monumental cock-up.'

The perception of another, older SAS veteran is that the

account given above places undue emphasis on physical bru-

tality. According to this source, the interrogation experts (who

include at least one former captive of the Chinese) regard

such brutality as counter-productive in breaking a prisoner's

will. Furthermore, he adds, candidates are carefully briefed

beforehand about what to expect from the interrogators. 'My

experience was that the Exmoor course emphasised psycho-

logical vulnerability,' he said. In practice, in his case, this

'psychological' approach meant his being left naked in the

snow for several hours before interrogation by a panel which

included a woman. The size of his penis, much reduced because

of the cold, was the object of sarcastic comment. This veteran,

a particularly hard man, added: 'I wasn't always certain who

was being trained: us or the interrogators. I think it was a bit

of both, really.' What is undoubtedly true is that, in action,

account given above places undue emphasis on physical bru-

tality. According to this source, the interrogation experts (who

include at least one former captive of the Chinese) regard

such brutality as counter-productive in breaking a prisoner's

will. Furthermore, he adds, candidates are carefully briefed

beforehand about what to expect from the interrogators. 'My

experience was that the Exmoor course emphasised psycho-

logical vulnerability,' he said. In practice, in his case, this

'psychological' approach meant his being left naked in the

snow for several hours before interrogation by a panel which

included a woman. The size of his penis, much reduced because

of the cold, was the object of sarcastic comment. This veteran,

a particularly hard man, added: 'I wasn't always certain who

was being trained: us or the interrogators. I think it was a bit

of both, really.`

The two combat-survival periods -- the preliminary SAS

course at Hereford and the Joint Services course at Exmoor --

end with a solemn, all-ranks dinner representing tastes acquired

during this time, including seaweed, frog, hedgehog and rat.

On one occasion, following total failure to obtain sufficient

hedgehog in the wild, rats were collected for the feast from

an Army veterinary establishment. 'What do you want these

for, then?' the SAS messenger was asked when he arrived to

pick them up. 'To eat, of course,' was the reply.

As well as resisting interrogation -- or at least, coming to terms

with the grim reality of it -- combat-survival training also teaches

escape and evasion. In winter exercises it is a long-standing

military joke that the SAS man may be identified as the one

who walks backwards across a patch of snow. The Joint Services

Escape and Evasion course devotes a short time to lectures and

demonstrations by police dog-handlers on eluding the dog by

wading in water or through a farmyard where the scent will

mingle with that of more pungent animals. SAS men are also

taught how to kill a war dog, a skill some of the regiment's

soldiers used to remarkable effect during an exercise in friendly

Denmark several years ago, to the outrage of the dog-handlers

concerned.

The final part of selection is for soldiers who have not completed

a parachute course to go to Brize Norton to do so. This is a holiday

compared to what the candidates have beem through, and most can`t wait

to finish it so they can come back to get badged. The handful of men

who complete the process of initial

selection and continuation training -- estimates of this number

vary between five and seventeen out of every hundred -- are

welcomed into the regiment by its commanding officer or

second-in-command, and handed the beige SAS beret and cloth

badge bearing the famous winged dagger.