Turkmenistan: An Overview

by

Iraj Bashiri

copyright 1999, 2003

Background

With an area of 189,370 square miles (488,100 sq km) the Republic of Turkmenistan is located

in the southwestern part of Central Asia proper. The most arid region of Central

Asia, it is bound by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the east, Afghanistan

and Iran to the south, and the Caspian Sea to the west.

Next to the Tajiks, the Turkmen are one of the

oldest peoples of Central Asia. They were among the first Turkish tribes to

arrive in Central Asia around the year AD 1000. They survived the Mongol invasion

by staying in the desert and subsisting by herding and plunder. During the last

decades of the nineteenth century, the Turkmen were involved in slave trade.

They attacked caravans, enslaved the members of the caravan and sold them in

the bazaars of Bukhara.

Called the Transcaspian Region, Turkmenistan

was ruled by Russia between 1890 and 1917. As a part of the Russian Empire,

Turkmenistan maintained its autonomy only to the degree that it could develop

its own language, culture, and nomadic way of life; otherwise, its affairs were

controlled by Moscow. Today Turkmenistan and Russia are trade partners. Russia

seeks a market for its manufactured goods, fertile land for growing cotton,

and new natural resources for its factories. Turkmenistan seeks Russia's help

for security against the Afghans and Iranians, especially against militant Muslims

who have dominated Tajikistan, infiltrated Uzbekistan and seek to destabilize

Kyrgyzstan. In any event, Turkmenistan exports natural gas, petroleum, and other

products to Russia and, in exchange, imports foodstuffs, heavy machinery, steel,

construction materials, and vehicles.

After the fall of

the Russian Empire, Turkmenistan was incorporated into the Soviet Union. In

1925, it became a Soviet republic. Under

Soviet rule, the Turkmen nation made a great deal of progress, especially in

agriculture and industry. |

|

Upon the dissolution

of the USSR in 1991, Turkmenistan became an independent nation. While

immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union, the former republics underwent

a period of austerity; Turkmenistan did not suffer as much. Its export of oil

and natural gas provided the Turkmen nation with enough income to retain its

standard of living at the level of prosperous Soviet days. In subsequent years,

especially in 1994, after Moscow refused to allow Turkmen crude to reach the

European markets through its territory, the Turkmen economy was negatively impacted.

Additionally, Turkmenistan's former European partners lost their ability

to pay their debts to Turkmenistan. The combination of these factors changed

the situation for the Republic. At the present, Turkmenistan tries to export

its oil and natural gas to Eastern as well as European markets through Afghanistan,

Iran and Turkey. Were that to happen, Turkmenistan's economic situation would

improve.

|

Geography

The topography of Turkmenistan consists

of flat to rolling desert with dunes. Its main features are the Kara Kum

Desert, which covers about 85% of the land and the Kopet Dagh mountain

range, located in the south. Altogether, the territory is recognized as

the driest region in Central Asia. The aridity and the harsh climate,

however, have a silver lining. Beneath Turkmenistan lies one of the largest

oil and natural gas reserves in the world.

Climate

Turkmenistan's climate is strongly continental

with frequent temperature changes. Although the average summer temperature

is around 60 F (or about 35 C), in the Kara Kum it can reach as high as

122 F (or 50 C). Conversely, the winter temperature may reach as low as

-27 F (or -33 C). The average rainfall is about three inches annually

in the lowlands and about 12 inches in the mountains.

|

Tourism

The ancient cities of Nisa and Merv hark to

the region’s ancient past and its medieval Islamic and Central Asian cultures.

The Sultan Sanjar Mausoleum and the seventh-century ruins at Kyz-Kala, very

close to Ashgabat, are reminders of the heyday of Turkmen ascendancy in the

region.

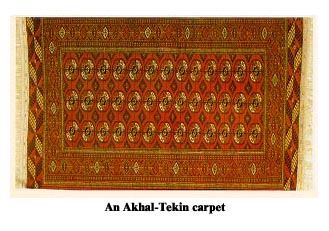

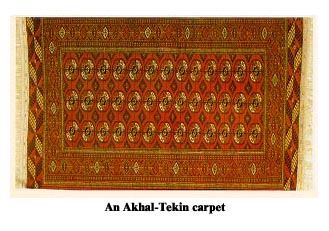

Some of the largest and finest woven carpets

in the world were woven here. Some of them are on display in Ashgabat’s

Carpet Museum. Other places of interest are the Turkmen History Museum and the

Turkmen Economic Achievement Museum. The handiwork of Ashgabat’s skilled

artists appears in the corner bazaars of the republic in the form of carpets

and earrings made of turquoise and cornelian. A row of four-star hotels built

in the early 1990s in anticipation of the oil boom that never materialized assures

the newcomer to Ashgabat of a place to stay.

|

|

History

From a historical point of view, the Turkmen

are descendants of the Oguz Turks of the 8th to the 10th centuries. As such,

they form one of the earliest layers of Turkish settlements in the region and,

consequently, have been assimilated more deeply into the Perso-Islamic culture

of the region. This assimilation is best understood in the nature of the towns

and villages of the region. In medieval times, due to their proximity to the

Silk Road, two major Turkmen cities prospered. One is the city of Khiva (now

in Uzbekistan), which controlled the farming in the region and was on the caravan

road to Russia and Europe. The other is the town of Merv that was in control

of the silk trade and of spices that flowed from the East to the markets of

Ray and Baghdad. In subsequent years, the town of Charju, in present-day Turkmenistan,

has assumed the traditional role of Khiva and the town of Mary has replaced

ancient Merv. The fate of Merv proper, however, is sealed, as long as the Kara

Kum Canal persists to erode the foundations of its massive ancient structures

and as long as vegetation continues to grow ever closer to the heart of the

old town.

From an ethnological point of view, the Turkmen

are the most distinctive of the Turkish peoples of Central Asia. Mentioned in

the Orkhon inscriptions of the 8th century, they belong to the Oguz tribal confederation

that moved west in the 10th century and formed the Seljuq dynasties of Iran

and Anatolia. In this sense, the Turkmen are more akin to the Ottomans and the

Azeri Turks than to the Turks of Central Asia. But like the Kazakhs, their loyalties

lie with the extended family, which encompasses clan and tribe, before it reaches

the State.

The Turkmen are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi

sect. Islamization of the region began early and was complete by the 10th century

of the Common Era. Some 86% of the population is Muslim.

Made up of a number of distinct tribes, the

Turkmen have retained their tribal divisions that include, among others, the

Teke, Yamud, and Ersari. Teke is the most dominant clan in the republic. In

Soviet times, it provided almost all the communist cadres and today continues

to make up a large number of the officials of the current government.

Turkmeni belongs to the Oguz division of the

Uralic-Altaic family of languages. It includes a number of dialects corresponding

to the tribal-territorial divisions of the Turkmen. Literary Turkmeni was established

at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century and is based on

the Teke dialect. Linguistically, too, the Turkmen are more akin to the Azerbaijanis

than to either their Uzbek or Kazakh neighbors.

Turkmeni script went through the same changes

that the scripts of the other republics underwent. From the end of 19th century

to 1929, the Turkmen employed an Arabic-based script. Between 1929-40, the Latin

script was introduced. Since then the Cyrillic script has been modified to meet

their daily needs.

Culture

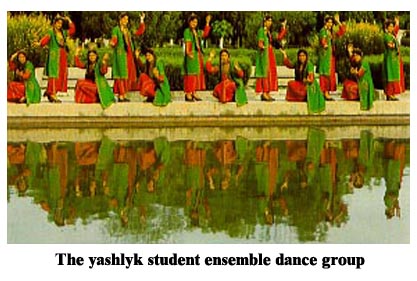

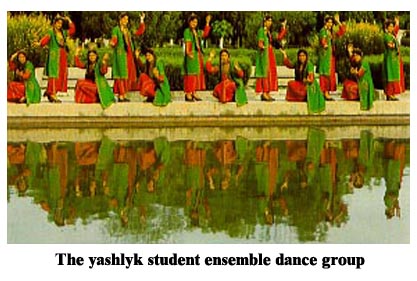

Turkmen culture is a nomadic culture at base.

Bravery and hospitality play a major role in shaping the old culture, as do

poetry and music. The poetry of Turkmenistan’s major bard, Makhdumquli,

exemplifies some of the rare nomadic values that have been changed by the Russians

and the Soviets who followed him.

Natural resources

The natural resources of Turkmenistan consist

of petroleum, natural gas, coal, sulfur, and salt.

Natural

hazards

The region’s only natural hazard is

earthquake. In 1948, an earthquake nearly wiped out the capital city of Ashgabat.

When an earthquake devastated Tashkent in 1966,

it was rebuilt by the Soviets within a short time. Not so for Ashgabat when

it was literally razed by earthquakes. Joseph Stalin did not even acknowledge

the occurrence of an earthquake. As a result of the earthquake, more so due

to a lack of attention to the people, the Turkmen intellectual pool that had

survived Stalin's purges was totally wiped out.

Environment

Desertification, salinization of soil, and groundwater

contamination through a misuse of chemicals and pesticides are some of the major

problems facing Turkmen authorities. Similarly, the Turkmen farmers are plagued

by poor irrigation methods that lead to water logging of the soil. Both the

Aral Sea and the Caspian Sea are polluted by hazardous waste put out not only

by Turkmenistan but also by Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Russia. In the case

of the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Iran, too, share the

blame. This situation has created acute medical problems in the area. The problems

are compounded by a poor diet, a lack of proper health care, and poor hygienic

practices. Family planning is another aspect about which little is known, but

which makes Turkmenistan rate first in infant mortality among the republics.

|

People

With a population of 4,200,000, Turkmenistan

has a labor force of about 488,000. Turkmenistan is one of the strictest

republics of the former Soviet Union both in terms of expression of individual

ideology and of enforcing autocratic authority. Saparmurat Niyazov, the

Republic's president for life, intends to keep the Turkmen away from the

political incursions of Russia as well as from the ideological inducements

of the Republic's neighboring countries. The capital of Turkmenistan is

the city of Ashgabat with a population of about 517,200.

Charju, Merv, Kerki, and Tashauz are the other major cities of the Republic.

Nationality

Turkmenistan’s ethnic mix includes 77

percent Turkmen, 9.2 percent Uzbek, 6.7 percent Russian, 2 percent Kazakh, and

5.1 percent other. The Russian population is usually higher in the cities than

in the rural districts. In Ashgabat, for instance, it might be as high as 40

percent as opposed to the 6.7 percent cited above. There are also 313,000 Turkmen

nationals living in Iran, 390,000 in Afghanistan, 170,000 in Iraq, and 80,000

in Syria. |

Health Care

Before the advent of the Russians into Central

Asia, the Turkmen tribes did not have any organized form of health care. Barbers,

traveling with the caravans, were often employed to perform certain medical

tasks. Learned men as well were often asked to prescribe drugs that had shown

positive curative effect on people in particular cases.

The Russians changed that system somewhat, but

they were not able to make it disappear altogether. When the Soviets took over

in the 1920’s, they were faced with the same problem. However, they came

up with a solution. Through education, they tried to make every individual to

be his or her own doctor. Helped by the European Soviets, Turkmen youths studied

medicine and entered the medical profession.

During the Soviet era, health care was free

of charge; it has remained so after the fall of the Union. Turkmen doctors,

however, worked mostly in tandem with Russian and other specialists. With the

fall of the Soviet Union, most of those specialists left, leaving the Turkmen

on their own. As a result, today, the republic’s hospitals and clinics

do not have good, trained Turkmen doctors, and they are continuously faced with

chronic shortages of nurses, pharmacists and pharmaceuticals.

The reports on medical technology in Turkmenistan

are mixed, by some accounts, today, Turkmen doctors are poorly trained, modern

medical technologies are nonexistent, and medicines are in short supply. By

some other accounts, the state is doing fine in spite of the departure of the

foreign specialists. The fact is that the state has monopolized health care

and is incapable of managing it properly. The reason, of course, is shortage

of funds. In other states, under similar circumstances, private doctors are

allowed to open practice. Turkmenistan, however, does not allow private practice.

If health care continues to operate as it has been during the last decade, the

chances are that the traditional healers, employing herbs and prayer, are likely

to reappear in the rural areas.

The major health problems in Turkmenistan are

cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and accidents. Life expectancy

is 58 years for men and 65 years for women. Infant mortality is estimated at

73 deaths per 1000 live births.

Education

Before the Russians and the Soviets came to

Turkmenistan, the education of the young was in the hands of the members of

the family. The Father taught his son all that he deemed necessary to know about

the herds, their feeding, watering, and protection. The mother taught her daughter

how to run an efficient household. Under the Soviets, a compulsory age for education

was fourteen. It remains the same today. The official languages of the republic

are Turkmeni and Russian. Uzbeki is spoken by 7 percent of the population. The

literacy level of the republic under the Soviets was 99 percent.

Turkmenistan’s major institutions of higher

learning are the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan (renamed the High Council

of Science and Technology, with President Niyazov as its head), the Makhtumquli

State University, the S. A. Niyazov Turkoman Agricultural University, and many

colleges and institutes, including the Seismology Institute. Due to political

interference in the curricula, some countries do not recognize the degrees granted

by Turkmenistan's universities. It should be noted also that not everyone is

allowed to enter high school and university. There are special tests that determine

whether an individual should be allowed to enter higher levels of education

beyond that which is mandatory.

Welfare

As nomads, the Turkmen did not have an organized

welfare system. The aged and the poor were automatically taken care of by the

tribe, as were children and the infirmed. The Soviets, who were responsible

for dismantling the tribal structures that supported the people, established

a welfare system that took care of all the needs outlined above.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, especially

during the early days of independence, natural gas, electricity, and drinking

water were to be provided to all households free of charge. The new Turkmen

government could do this because it received a great deal of money as a result

of a sharp rise in the price of oil.

Additionally, plans were put in place

to increase the minimum wage and subsidize food and other necessities. Ideally, families were to own houses,

cars, and telephones and there would be no needy individuals in the republic.

Today, only Turkmenistan's pensioners, the disabled,

and children receive payments. A fund was established to which all the employees,

employers, and the state contribute. As a result, Turkmen nationals receive

free gas, water, electricity, and salt. Flour has a fixed low price and public

utility services receive token fees. This needs to be emphasized that were it

not for the export of oil and natural gas, the Turkmen would not have been able

to maintain the standard of living that they had enjoyed under Soviet rule.

|

|

Housing

As nomads, the Turkmen lived in yurts or yurtas.

A Yurt is a round structure, the

size of a large room. In it, there is a left side (er jak), for men, where there is space for saddles and whips,

and a right side (epchi jak) for

women, where there is space for domestic items. There is little privacy in a

yurt. For the newlywed, a curtain

(koshogo) temporarily separates

their space. The yurt has a fireplace

for making tea and for cooking, and an opening at the top (tunduk) for the smoke to leave and the sun to shine in. As

the family grows, the number of yurts in the clan also grows.

When the Soviets settled the Turkmen tribes

by force, they also changed their way of life. Most Turkmen were moved to government-subsidized

apartments in villages and towns, while some others, especially herders, continued

to dwell in yurts. After independence, housing continues to be free of charge in towns and

villages. More than 70 percent of the urban and 10 percent of the rural houses

belong to the state. There is, however, a chronic housing shortage. The situation

is worse in the major urban centers, especially in Ashgabat.

Religion

The Turkmen are primarily Sunni Muslims of

the Hanafi school (89 percent). Originally they were Shamanists. Some of their

Shamanist practices of the past influence their faith. There are also some Eastern Orthodox (9 percent), and other

religions (2 percent) in the republic.

Language

The official language of Turkmenistan is Turkmen

or Turkmeni. Russian, which was the official language during Soviet rule, is

now the language of intercultural and international communication. Russian is

also used in government affairs and in business. Uzbeki is also spoken by a

segment of the population that is close to the border of Uzbekistan.

Government

The name of the republic is Turkmenistan. It

is a republic with its capital at Ashgabat. Administratively, the republic is

divided into 5 provinces. Turkmenistan became independent on October 27, 1991.

A constitution was adopted on May 18, 1992. Turkmenistan’s legal system

is based on civil law with suffrage at 18 years of age.

The Executive branch consists of a chief of

state or President. He is both the chief of state and the head of government.

The president appoints the cabinet or the Council of Ministers. Under the 1992

constitution, the legislative branch consists of two parliamentary bodies, a

unicameral People's Council (100 seats, some elected by popular vote and some

appointed; meets at least yearly) and a unicameral Assembly (50 seats; elected by popular vote for

five-year terms). The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court. The president

appoints all judges.

Political parties

Formal opposition

parties are outlawed in Turkmenistan. There are, however, several unofficial,

small opposition movements both underground in Turkmenistan, or in foreign countries.

The most prominent opposition group-in-exile is Erkin, based in Moscow. There

is also another opposition group called the Democratic

Party of Turkmenistan.

In order to

develop its resources independently, Turkmenistan has asked Russia and the other

CIS republics to stay out of Turkmen affairs. To this end, Saparmurad Niyazov,

like Stalin before him, has created a cult of personality around himself. This

has worked so far in keeping the opposition at bay and maintaining stability.

But it remains to be seen for how long such an iron-fisted approach to the resolution

of ideological problems will last. A positive point in favor of Niyazov is that

the Turkmen government, too, intends to keep Islamic fundamentalism away from

the borders of the Republic.

Present-day Turkmenistan, even though calm and

collected on the surface, is rife with problems. In fact, thinking about these

problems brings the term oxymoron to mind. The Turkmen wish to privatize and

become a democratic nation; but they also wish to retain their Soviet-style

structure. They share the same ecological problems that the other republics

experience, but have failed to garner the political freedoms they enjoy. Similarly,

they wish to attract foreign investment and foreign technology to develop their

natural resources, but must keep the foreigners at arm's length lest they foment

discord.

The most pressing problem of Turkmenistan is

lack of freedom, which makes of the Republic a veritable test case for gauging

the power and reach of Islamic ideology. Can it penetrate deep enough into the

social, political, and cultural fabric of Turkmenistan to stimulate its so-far

silent intellectuals?

Turkmenistan's main areas of concern rest outside

its border. Helped by Russia, Iran is planning the building of a major nuclear

station in its northeastern territory, near the Turkmen border. This has created

a dilemma because Iran is also agreeing to allow Turkmen crude to reach Europe

through its land. Helped by Saudi Arabia and other interested parties, Islamic

militants have dominated Tajikistan, infiltrated Uzbekistan and seek to destabilize

Kyrgyzstan. How long will it take them to penetrate Turkmenistan?

Flag

|

Adopted 1992

green field with a vertical red stripe near the hoist side, containing five carpet guls (designs used in producing rugs) stacked above two crossed olive branches similar to the olive branches on the UN flag; a white crescent moon and five white stars representing the five regions of Turkmenistan appear in the upper corner of the field just to the fly side of the red stripe

|

Democratization

General Introduction

In order to understand

the economy of the republics of the former Soviet Union, it is necessary to

understand how centrally controlled economies work and how a centrally controlled

economy is changed into a market economy.

In

simple terms, the Communist Manifesto gave birth to a number of economies in

Central Asia all of which were controlled by the state. The articles

of the Manifesto asked for a total, central control of all aspects of life.

In other words, all the peoples’ assets were taken from them and placed

under the supervision of the State. This included the factories, plants, and

natural resources, as well as human resources.

Privatization is the

reverse of centralization. It requires a centrally controlled state that wishes

to become a modern independent state to decentralize its agriculture, industry,

businesses, and housing. It requires that the individual be given the right

to buy and sell property. Means of transportation, production, and communication

should be placed in the hands of the people. Similarly, the state should decentralize

its banks, allow foreign investment to help develop its resources, and become

a party to local and international efforts in running a meaningful and profitable

market economy.

A truly independent

republic cannot ignore freedom. It must allow its population the right to free

speech by placing the media (newspapers, radios, and televisions) in the private

domain and by removing censorship. Additionally, people should be given political

freedom so that they can form political parties, stand for election, and vote.

What was outlined above

serves as the basis for creating a democratic state with a stable government.

A republic with a parliament that respects international law and which legislates

laws that are sensitive to ethnic, racial, ideological, national, and gender

concerns of the people, a government that recognizes equal opportunity and equal

rights of its people.

Finally, an independent

state must create access to education and health care through state and private

welfare programs, it should form committees to oversee its conduct of human

rights, as well as a committee to handle abuse of natural resources.

Since receiving their independence, the republics

in Central Asia have responded differently to the demands of independence, especially

with respect to privatization, political freedom, and human rights issues. The

difficulty does not rest with the republics as much as with the nature of changes

that are required of them. Obviously these changes cannot be meaningfully implemented

unless those receiving the changes are cognizant of the rules of democracy.

As every one knows, the road to democracy is long. It requires sacrifice as

well as a large amount of funds for educating the people and making them understand

the working of the law vis-à-vis the rights of the individual and the

community.

Economy

Turkmenistan's economy is based on agriculture,

livestock raising, and the textile and oil industries. Long-fibered cotton,

wheat, alfalfa, grapes, and melons are among the agricultural products most

produced in the collective farms of the Republic. At the heart of Turkmen agriculture

is the 1,000 kilometer-long (625 miles) Kara Kum Canal, an artificial waterway

that has created prosperity for Turkmenistan but visited irreparable devastation

on many Kazakh, Karakalpak, and Uzbek settlements whose inhabitants draw on

the Aral Sea for their livelihood.

Before the Soviet takeover of Central Asia,

the Turkmen tribes were not settled. They were nomads, moving constantly from

place to place in search of grass and water for their animals. The Soviets settled

the Turkmen tribes, created an agricultural base next to their already existing

livestock-raising base, and enhanced the complex by adding industry to utilize

the abundant resources of the republic. Once the main components were in place,

Turkmenistan’s agriculture was collectivized and mechanized. Then both

the agriculture and the industry were placed under the direct control of the

center in Moscow. Before long, the republic could provide fertilizer and machinery;

in time, it became one of the major grain and cotton contributors to the Soviet

economy. Agriculture was diversified in the 1980’s by the addition of

planting fruits and vegetables. Unlike the other republics that abandoned the

Soviet system either totally or partially, in Turkmenistan the state-order system

continues to mandate cotton and wheat crops per quotas. Today, one half of Turkmenistan’s

irrigated land is planted in cotton. The world’s tenth largest producer,

the cotton sector employs nearly half of Turkmenistan's work force.

Agriculture

Only four percent of Turkmenistan's land mass

is arable, the other 96 percent is covered by the Kizil Kum desert and the Kopet

Dagh mountains. Thanks to the 1000-kilometer Kara Kum Canal and a network of

other irrigation works, Turkmenistan remains a major producer of cotton. In

addition to cotton, Turkmenistan's other major crops include grains and fodder.

Livestock raising is another contributor to Turkmenistan’s economy. Cattle,

sheep, goats, camels, and horses create a profitable market in hides, wool,

meat, and milk. The contribution of the soft, curly wool of the Karakul sheep

can be added to this.

|

Camels and sheep constitute most of Turkmenistan's

livestock raising. Turkmenistan's Persian lamb, produced in large numbers under

modern conditions, is among the most sought after worldwide. Similarly, Turkmenistan

is well known for its carpets, cotton, wool, and silk textiles.

When the Soviets tried to create a complex of

agriculture and animal husbandry in Turkmenistan, they faced a major problem.

The republic’s rivers--the Amu Dariya, Murghab, Tejen, and Atrak--all

flow in areas that are quite distant from the main arable lands. The Soviets,

therefore, created a system of canals around a main canal, the 1000-kilometer

man-made Kara Kum Canal. Once this major project was completed, Turkmenistan's

area of arable land increased, boosting the prosperity of the surrounding area,

especially Ashgabat. |

|

While in the past, the country had been a patchwork

of unrelated waterholes, it now

became a network of interconnected oases each serving a particular agricultural

or industrial purpose. For instance, the Murghab oasis contributes fine-staple

cotton, carpet, silk, and Karakul pelts. Similarly, the Amu Dariya oasis, centered

on Charju, contributes cotton, silkworm, and fiber crops. The Kopet Dagh oasis,

centered on the capital city of Ashgabat, serves as Turkmenistan's industrial

center involved in oil extraction and refining, also as the center of chemical

and mining industries and the republic’s fisheries. In fact, extraction

and processing of petroleum and natural gas remain the republic's major industrial

ventures. Plants that produce construction

materials, agricultural fertilizers, and food and process wine are secondary

to this.

Industry

Turkmenistan commands the world's third largest

sulfur deposit and the fifth largest natural gas reserves. Its supply of fossil

fuels, estimated at 700 million tons, is sufficient to meet 100 percent of its

own energy needs. Additionally, Turkmenistan has a number of major rivers that

can contribute to the prosperity of its industry through the generation of hydroelectric

power. In addition to petroleum

and natural gas, Turkmenistan has a number of other mineral resources including

coal, gypsum, mercury, iodine, and phosphate, raw materials used in cement and

glass production, as well as various types of salts.

Carpet making and leather working are two major

Turkmen traditional industries for which the republic is well known. Similarly,

Turkmenistan has a reputation as a source of good quality raw silk and silk

textiles. As a part of their reorganization of the agricultural and industrial

bases of the republic, the Soviets established special plants in the republic’s

center for the production of silk textiles. Today, the number of plants that

specialize in the production of hand-woven silk and Turkmen carpets, especially

in the capital city of Ashgabat, has increased.

|

Turkmenistan’s industry, however, has to make a difficult choice. On the

one hand, it needs foreign investment and expertise to extract and market its

abundant resources; on the other hand, it cannot allow Islamic extremism and

Western ideologies to enter the republic and corrupt the minds of its people.

As a chief, President Niyazov knows well that he must allow his people and others

to develop the resources of the land for the common good. But he also knows

that the experiences of the other republics, especially Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan,

have not been encouraging. As a result, he vacillates between two worlds, wondering

whether he should sign a major proposal, like the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline

and the Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline, or he should be satisfied with sporadic agreements

with Russia, the CIS, and Iran

.

It is this same kind of thinking that has prevented

one of the largest oil and natural gas reserves of the world from competing

in the international arena for development. After the fall of the Soviet Union,

Turkmenistan chose the path of political and economic neutrality as opposed

to either joining the global market or adopting an import substitution economy

plan. Consequently, the outcome of Turkmenistan’s economic growth, i.e.,

its privatization project and the way it relates to the international market

differ from its neighboring states. This road, although difficult, is not alien

to the Turkmen. Turkmenistan does not pretend to be a democratic state. It has

chosen a president for life, Saparmurad Niyazov. As the sole decision maker,

he can direct the affairs of the country in any direction that he sees fit.

|

Privatization

Privatization comes to the Turkmen as a new

thing. It should not since Islam respects personal property and defends an individual’s

right to property against all infringement. At the same time, lands and businesses

are first and foremost the property of the sultan and amir. They have captured

them from the infidel; their descendants have defended them and regulated their

affairs in the past. Naturally, giving up the right and authority over such

properties and enterprises comes easily to the Central Asian rulers in the 21st

century. Niyazov, the President of Turkmenistan, is no exception. He prefers

a good administration to any kind of privatization as the correct path to a

truly socialist state.

Privatization in Turkmenistan has moved very

slowly. By 1992, only 2,600 small trading outlets and home-worker operation

enterprises had become privatized. In the following year, a few more small trade

and service enterprises were sold to foreign buyers but the ownership of large

manufacturing firms and the private ownership of service-sector enterprises

with fewer than 500 employees was never discussed. The privatization effort

in Turkmenistan peaked in 1994, when 1000 small service sector enterprises were

privatized.

Banking

Turkmenistan’s banking system is centrally

controlled. It consists of the

State Central Bank of Turkmenistan, two state banks, the State Bank for Foreign

Economic Affairs (or Vnesheconombank), and the State Savings Bank (Sberbank).

There are also 13 commercial banks that include 4 banks with foreign capital.

There are also 52 Daykhanbanks that deal with agricultural production. The commercial

banks are generally small-and medium-size; their major shares belong to the

state enterprises.

Turkmenistan's currency, the Turkmen manat,

was introduced on November 1,1993. The governmental exchange rate was established

in 1996. One US dollar is worth 21,000 Turkmen manats.

Exports

and Imports

During the Soviet

era, Turkmenistan did not have either diplomatic or economic relations with

the free world. The major partners in its economy were the other Soviet republics,

especially Russia. In fact, Turkmenistan was obliged to produce certain products

for export and import some products that it was not allowed to produce.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the situation

changed. Rich in natural gas and petroleum, Turkmenistan sought trade relations

with Iran and Turkey. This move forced Russia, in 1994, to refuse to let Turkmen

crude to reach Europe using its pipelines. In December 1999, the decision was

reversed. Lack of export routes

continues to plague the Turkmen economy. More recently, the republic has been

negotiating with China, the United States, and Russia for export of its natural

gas.

|

Exports

Turkmenistan's main exports include petroleum,

natural gas, minerals, chemicals, cotton fiber, textiles, and processed foods.

The republic's total exports in 2001 were estimated at $2.7 billion. This figure

indicates a rise that is the result of higher international oil and gas prices.

Turkmenistan's export partners are Ukraine, Iran, Turkey, Switzerland, Mexico,

and the Far East.

Imports

Turkmenistan's main imports include food and

beverages, textiles, machinery and equipment, and foodstuffs. The republic's

total imports in 2001 were estimated at $2.3 billion. Turkmenistan's import

partners are Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, United

Arab Emirates, France, and Germany. Turkmenistan's total imports in 2001 were

estimated at about $1.5 billion.

|

Balance

of Payment

In 2001, Turkmenistan received $16 million in

economic aid from the United States. With respect to Turkmenistan's exports,

it is significant to note that directly after the fall of the Soviet Union,

Turkmenistan's imports increased considerably. By 1994, however, as the former

Soviet republics failed to pay their debts, Turkmenistan's imports have decreased

considerably. In fact, the standard of living of the republic that is tied directly

to its exports has fallen below the poverty line.

Turkmenistan’s external

Debt is estimated between $2.3 billion to $5 billion . In 2001, Turkmenistan

received $16 million in economic

aid from the US.

Communication

The general state of Turkmenistan's communication

lines and service is poor. In 1997-98, There were 363,000 main and 4,300 mobile

cellular lines in the republic. Turkmenistan is linked by cable and microwave

radio relay to the other republics of the CIS. It is connected to the other

countries by leased connections to the Moscow international gateway switch.

There is also a new telephone link from Ashgabat to Iran and a new exchange

in Ashgabat switches international traffic through Turkey via Intelsat; satellite

earth stations - 1 Orbita and 1 Intelsat. There are 16 AM, 8 FM, and 2 shortwave

stations and 3 Television broadcast stations.

Programs are generally relayed from either Russia or Turkey.

The Internet country code for Turkmenistan is .tm. There is one internet service

provider and about 2000 Internet users.

Transportation

Turkmenistan has a total of 22,000 km of highway,

18,000 km of paved and all-weather gravel-surfaced roads, as well as 4,000 km

of unpaved roads. These latter, made of unstable earth, are often difficult

to negotiate, especially in wet weather). There is also a total of 2,440 km

of railway. Additionally, the Amu Dariya serves Turkmenistan as an important

inland waterway. Crude oil and natural gas move through 250 km and 4,400 km

of pipelines, respectively. In 2001, Turkmenistan had 76 airports, 13 with paved

runways.

Military

Turkmenistan’s military consists of

an army, air and air defense, navy, border troops, and internal troops), as

well as a national guard. The recruitment age is 18. Available military manpower

at the present is 1,239,737. The manpower fit for military service is 1,005,686.

A Russian air-ground force of 34,000 is jointly controlled by Turkmenistan and

Russia. Turkmenistan’s annual military expenditures are $90 million.

Border

Issues

With respect to sharing of the water of the

Amu Dariya, Turkmenistan shares some of the same problems that the other republics

of Central Asia experience. A larger problem for Turkmenistan, however, is the resolution of the division of the

Caspian seabed and the oil reserves beneath it. Currently, the seabed is shared

among Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Iran. Turkmenistan's

boundary problems with Kazakhstan are currently being discussed.

Turkmenistan serves as a transit country for

Afghan narcotics bound for Russian and Western European markets. There is a

limited amount of illicit cultivation of opium poppy in the republic for domestic

consumption. The government often mounts small-scale eradication of illicit

crops projects but has not been able to make much headway.

See also:

Central Asia: An Overview

Azerbaijan: An Overview

Iran: A Concise Overview

Kazakhstan: An Overview

Kyrgyzstan: An Overview

Tajikistan: An Overview

Turkmenistan: An Overview

Uzbekistan: An Overview

Top of the page

Home| Courses