Three-Dimensional Vectors |

See this page's Maple Code |

|

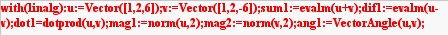

I. The Three-Dimensional Coordinate SystemWe will look at 3-d vectors mainly in component form, and so we first need to define the 3-d coordinate system. We still have the x- and y-axes, of course, and to create our third dimension we add a z-axis. It is customary, however, to shift our view of the x- and y-axes, by letting the x-axis come "straight off the page" and defining y as the horizontal axis. This leaves the z-axis as the vertical scale, as shown on the left. Because of the physical difficulties of plotting three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface (your screen), the actual coordinates of points (and thus the components of vectors) can be rather vague if we don't use labels. Fortunately, using Maple we can always adjust our view to get a better sense of what's going on, as in the rotating graph below where we see vectors  and and  from several angles. from several angles. |

| All operations defined for two-dimensional vectors are also defined for three-dimensional ones: we can add, subtract, scalar-multiply and dot-multiply vectors. We can still find a vector's magnitude, only now we must take three coordinates into account; in the same way, the dot product will use two trios of coordinates instead of two pairs. For our vectors on the right, some simple examples would be

And we can still find the angle between the vectors using our dot product formula:

|

Click here for animation code |

|

|

III. The Cross Product With our extension into three dimensions, we now define a third type of multiplication: the cross product (sometimes called the "vector product"). The notation is u x v, which is read "u cross v," and the result is a vector that is perpendicular to both u and v (see the diagram). The general formula for calculating the cross product of With our extension into three dimensions, we now define a third type of multiplication: the cross product (sometimes called the "vector product"). The notation is u x v, which is read "u cross v," and the result is a vector that is perpendicular to both u and v (see the diagram). The general formula for calculating the cross product of  and and  makes use of a 3 x 3 determinant: makes use of a 3 x 3 determinant:  where vector i (1,0,0) is the unit vector along the x-axis; vector j (0,1,0) is the unit vector along the y-axis; and vector k (0,0,1) is the unit vector along the z-axis. It is straightforward to show (using the dot product) that u x v must be perpendicular to both u and v. |

IV. The Area of a Parallelogram One of the properties of u x v is that its magnitude is equal to the area of the parallelogram defined by u and v; for our example vectors we would then have One of the properties of u x v is that its magnitude is equal to the area of the parallelogram defined by u and v; for our example vectors we would then haveAnd this is easily confirmed as the area of the parallelogram:

|

|

Return to Main Vector Page |

Go to 2-D Vector Page |

Go to Applications of Three-dimensional Vectors |