The Nature of Form: A Layman's View of Organic Architecture - Eric Hunting

Introduction: In his book "The Millennial Project" author Marshal Savage notes the use of 'organic architecture' as an important feature of the Aquarius marine colony. Other futurists have also mentioned this form of architecture as being important to the design of future habitation and the Nexus marine colony, proposed by architect Eugene Tsui, also makes use of this style. But what exactly is this organic architecture? A search through the architecture section of the typical library is unlikely to provide a single title that even mentions this phrase. Our only clues to its nature are often found in the works of futurists and science fiction writers and rarely adequately described or illustrated.

Having followed this very unique form of architecture for many years, I decided that it would be helpful to fellow alternative architecture enthusiasts to develop a simple article that fully describes and defines organic architecture, providing clues to its further study and insight into its application. This is a layman's work and must not be considered authoritative but I hope it will be useful to those intrigued by this unusual area of architecture.

There are today three distinct architectural disciplines which go by the name of 'organic', each founded on different principles and yet all embracing the ideal of creating 'optimal' or 'ideal' architecture. Though these disciplines have, in the past, been pursued in relative isolation of one another-and indeed of mainstream architecture in general-they are uniquely complimentary in nature, suggesting a possible synthesis of the three which has yet to be realized. In this article we will explore each of these disciplines in turn, looking at the principles on which they are founded and existing examples of their use in order to understand how they relate to each other. In essence, we shall attempt to definitively answer the question; what is organic architecture?

The Origin of Architecture: Before we can examine these three organic disciplines we must understand their common origin; Primary Architecture. Each of these disciplines was conceived with the realization that there exists a kind of subtle and overllooked sophistication in the vernacular or 'everyday' architecture of our most ancient civilizations. I refer to this as primary architecture, after the term 'primary culture' used by anthropologists to describe the tribal hunter/gatherer cultures and early agrarian communities of pre-history and contemporary indigenous peoples. Primary architecture is founded in the basic survival need for shelter and yet while seeking to fulfill this need our ancestors were compelled to express themselves through their simple structures, applying ornament and style to their simple materials and establishing traditions of construction technique, thus laying down the foundation for all architecture as we know it today. Limited to the materials provided by nature herself, early man's architectural expressions became a kind of dialogue with nature and it is in this dialogue that we find a kind of sophistication, a sensibility about order, form, and craft, which has been lost in the poly-cultural, technological, political, and commercial cacaphony of contemporary architecture. This natural dialogue is what has attracted the attention of many of the most legendary architects of the 20th century, compelling them to seek to re-establish it in contemporary architecture and thereby re-establish a kind of harmony with nature often attributed (occasionally falsely) to our early ancestors. Therein rests the origin of organic architecture and, as we shall see, it is from differing perceptions of this original natural dialogue that the three different disciplines of organic architecture have emerged.

As with most things in architecture, it is difficult to get the point by description alone. We need a physical, or at least visual, point of reference. Luckily there is a simple example which more-or-less sums up the essence of primary architecture -at least in this author's opinion- and which we can use as a frame of reference to understand what it is about this early architecture which has so inspired organic architecture.

[re-creation of African spiral hut from Puerto Vallarta villa in Mexico]

And here it is, the African dung hovel. This simple hand formed structure is perhaps the earliest and simplest of all free-standing dwellings and is still in use today in Africa and elsewhere. The structure is the epitome of functionalism, made from a material, dung, straw, and earth, readily available to the cattle herding tribes. A single monolithic spiral wall comprises the whole structure. Closed in on itself, this wall not only encloses the maximum area with a minimum of material, it forms its own self-sheltered doorway. Sometimes the wall is lowered in height past the doorway and extended outward as a low fence wall around the dwelling. Alternately, a second similar wall is built around the dwelling, made of the same materials or of thorny bushes and sticks used as a corral for domesticated animals and protection against nocturnal predators. Topped by a thatched roof, the structure is perfect in its efficiency and yet has a singular elegance unmatched by any product of our supposedly sophisticated modern civilization. It is this unque and almost universal characteristic of primary architecture which most intrigues contemporary architects. Put aside your preconceptions about 'primitive' societies. Forget about the question of whether you would or would not want to live in such a simple house. That's beside the point. Consider the structure, the relationship between the form, the material, and the surrounding environment. This structure represents the soul of organic architecture in all three of its definitions.

Organic by Nature: Perhaps the first architect to specifically use the term 'organic architecture' was Frank Lloyd Wright who used the term to describe a type of architecture which achieved an elemental harmony between the man-made environment within the home and the natural environment outside. If it had been named today it probably would have been called 'wholistic' architecture, though that too is a term subject to some confusion due to its use by the so-called parasciences. A great deal has been written about the work of Frank Lloyd Wright because, in America at least, there is an unfortunate tendency to see American architecture as beginning and ending with Wright. Many authors have tried to explain the singular nature of Wright's work and there is even a Prairie School of architecture, founded by Wright, which attempts to perpetuate-with frankly mixed results-this unique approach to design. But if we fan away the cloud of academic rhetoric that surrounds Wright's work today we find a fairly straightforward and simple set of principles traced back to that simple hovel ilustrated above.

Wright defined his version of organic architecture when he said; "Organic architecture sees actuality as the intrinsic romance of human creation or sees romance as actual in creation... In the realm of organic architecture human imagination must render the harsh language of structure into becomingly humane expressions of form instead of devising inanimate facades or rattling the bones of construction. Poetry of form is as necessary to great architecture as foliage is to the tree, blossoms to the plant, or flesh to the body." What Wright was basically getting at here was that the form of a structure should enter into a poetic dialogue between its environment and it inhabitants. Another quote from Wright gets to the heart of this idea. "My prescription for a modern house: first pick a good site. Pick that one at the most difficult site- pick a site no one wants- but one that has features making for character: Trees, individuality, a fault of some kind in the realtor mind." The sites he's talking about are sites which are, in a word, rugged. Places where the terrain and surrounding natural environment impose their tacit will upon the form of a structure and thus require the architect to accommodate nature as much as the desires of the inhabitants. A location that forces you to enter into that dialogue with nature if you are to use the site at all as opposed to the conventional bull-dozed flat suburban housing lot where nature is obliterated and the environment simply manufactured and compartmentalized.

Wright's chief goal in his work was to establish an indigenous American architecture, this because he observed that virtually all contemporary American architecture had ts roots in European and Classical architecture and, quite often, merely parodied it. Just as landscape painting defined the basis of original American art, so too Wright saw the uniquely beautiful and dramatic American landscape as the natural inspiration for an indigenous American architecture. But ironically, in searching for a foundation for this new indigenous American architecture Wright turned to Asia for there he saw a kind of interplay between nature and artifice which he also found mirrored in the truly indigenous but sadly lost architecture of the native Americans. (quite an insight, I might add, since at that time the theory of native American migration from Asia was still not entirely accepted in the academic community) In Asian architecture Wright discovered a set of principles which defined a poetic dialogue with nature which we can see demonstrated in the typical Japanese garden.

We can see these principles at work by looking at the small stream which is almost always a component in the traditional Japanese garden and which passes in through an opening in one garden wall and exits out another. Likewise, we will often see multiple gateways through different sides of the garden and adjoining buildings which define pathways through the enclosed environment. Frequently, we see that the organization of elements in the interior of a home has been designed in relation to the exterior ones, to the trees, rocks, streams, and such which establishes a kind of intellectual pathway linking the interior and exterior. Often elements of the outside world are brought wholely inside, such as rocks, flowers, miniature trees, landscapes painted on screens or wall hangings, or simply natural materials left with little change to their shape, color, and texture. The basic idea here is to achieve a kind of continuity between what is inside the garden or the home and what is outside. Between the artificial world created by man and the natural world beyond it. Without this continuity the artificial environment, no matter how large or lavishly furnished you want to make it, becomes confining. It becomes a prison. It becomes detached from reality. With this link the artificial environment becomes rooted in space, time, and nature like a tree. It becomes a sheltered and comforting still point along those various paths where one can rest and work.

We can see this principle at work in the African dung hovel. Why a spiral wall instead of a circle? You could leave a uniform circle open at the doorway and get roughly the same degree of access, right? However, if the wall was a circle the opening would leave a portion of the space exposed to the elements, forcing you to create some kind of rigid door to close it off. The spiral wall needs no door to provide adequate shelter and at the same time it establishes a flow between the space inside the spiral and the world outside. It is never wholely enclosed. This is the same kind of continuity one finds at the heart of Wright's organic architecture.

Despite his numerous trips to Asia, Wright denied any direct influence from Asian architecture but it is apparent that, though he may not have been influenced by Asian architectural styles, he was clearly influenced by Asian ideas about architecture and its relationship to the natural environment. Indeed, it may be fair to refer to Wright as a Zen or Taoist architect since he sought much the same balance and harmony with nature Zen and Taoist ascetics have sought through their art, landscaping, and architecture. And like them Wright regarded the existing natural environment of a building site as the context for the structures he designed within it-an idea as radical in the western world today as it was early in the 20th century. I believe that this was something Wright first sensed in the primary architecture of native Americans but was unable to fully grasp from the ruined remains of their structures alone. He needed to see it at work and intact as it is in Asia.

Wright also blended modernism into this mixture, recognizing the potential that modern materials and engineering offered in terms of supporting structural shapes and forms not possible with earlier materials and methods. Wright was one of the few American architects of his time to make extensive use of concrete, which was generally considered a 'homely' and uncomfortable material and which did not see widespread use until after WWII. Modernism also offered yet another kind of natural harmony; the harmony of mathematics.

At the beginning of the 20th century western society began realizing a mass perception of a 'higher' nature made tangible through physics and new technologies and which saw its structure defined by mathematics. Nature was no longer simply a tangible realm of flora, fauna, and landscape. It was also a sublte and invisible realm of cosmic rays, radio waves, magnetic fields, the structures of molecules, and orbits of planets. This subtle nature was brought into tangibility through mathematics and its pythagorean visualizations which modernism appropriated and applied to art and architecture. This idea of a kind of cosmic harmony is the heart of modernist architecture. In addition to pursuing optimal structural efficiency through advanced materials and precision engineering and using the wizardry of technology to make materials perform in new and startling ways, the modernist architects believed their designs could also inspire a sense of serenity through harmony with this higher nature. And, in fact, this is often the case in the more sophisticated modernist designs.

It would be wrong, however, to regard Wright as a modernist since unlike the modernists Wright did not embrace harmony with this higher form of nature to the exclusion of the organic realm. He treated it as another part of the spectrum of nature which needed to be considered equally. As a consequence even his most modernist works exhibit an organic quality and sensibility the true modernists only came to understand later in this century-when the computer, the fractal, and chaos theory further refined the popular culture's perception of that higher nature.

So how do we sum up organic architecture as defined by Wright? As a synergy of artifice and nature framed by the context of individual landscapes. The plan of one of Wright's organic structures is at first dictated by the existing landscape of the site and often by the organization of natural elements like trees, water, and rocks in that landscape. His buildings tend to reside within the natural spaces offered by the existing landscape rather than employing the typical practice of clearing and leveling the landscape to suit the structure. The plan is designed to establish an optimal flow for movement within the structure as well as through it from the outside. It is also intended to take advantage of natural lighting and solar thermal heating as well as to accommodate seasonal changes rather than merely resisting them.The design of the structure takes into account the colors, textures, and seasonal changes in the natural landscape. His modernist leanings drove a preference for stacked rectilinear and clustered radial forms and overhanging planes. Many of his most famous structures made use of cantilevered structures which were made possible only by the use of modern materials like steel reinforced concrete. Windows were often large and located to frame exterior views as though they were part of the interior decor. His use of furniture was farily conventional but he also liked to take advantage of plan features to create seating, table, and shelf space that was integral to the walls and floors.

Wright was not minimalist in his approach to interior design nor did he tolerate clutter. He seemed to prefer the use of decoration which was sublime and which was in some way integral to the architecture itself or the materials it was composed of, such as roughly cut stone or wood, molded cement ornaments, decorative lighting, and stained glass. Discrete pieces of furniture were often designed to synchronize with the overall design of a specific building, rather than being generalized as most furniture is. He often employed Asian modes of ornamentation but the stylings were also often imspired by the art of native Americans, especially native sand painting, as well as modernist cubist art. A rich combination of materials was typical. A single building might employ a variety of wood, stone, ceramic, glass, and masonry employed just like paints in an artist's pallet. The use of paints and other wall coverings was uncommon. Wright believed that the natural state and color of materials were decoration enough. He apprently did not prescribe to the belief in renovation for the sake of novelty and tried to fine tune his designs to preclude the desire for such renovation. As his fame grew this was not difficult to achieve since the owner of a Wright designed home would often be no more inclined to change it than he might change a fine work of art.

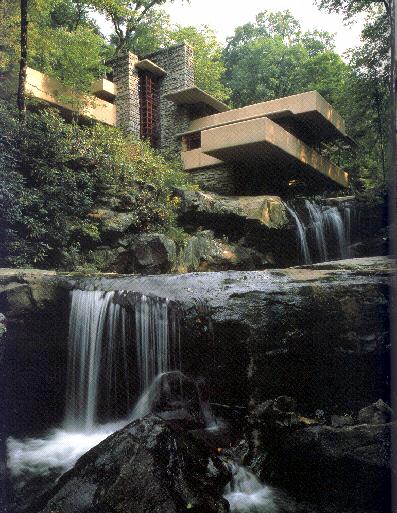

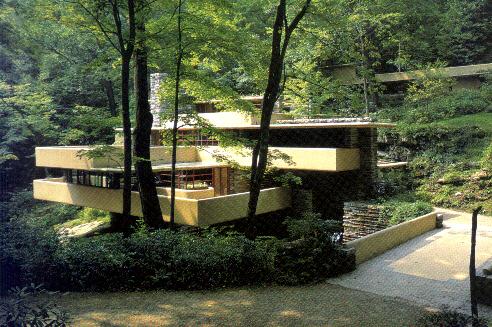

One work perhaps epitomizes Wright's organic architecture concept; the much touted Falling Water in Mill Run Pennsyvania.

[views and interior of Fallingwater, PA - Frnak Lloyd Wright]

In this elegant design we can see the organic concept employed to perfection. We can see all the influences behind it fused in perfect harmony with the surrounding natural environment. We see the sensibilities of Asian architecture expressed in the waterfall and the flow of passages through and around the structure. We can see the rounded edged forms and earthen tones of native adobe. The clustered shapes of the pueblo perched on the edge of the cliff like ancient cliff dwellings. The overhanging planes of the Japanese roof and the grid-like framework of the Japanese screen partition. The stepped pyramid shape of the pre-columbian temple. And the smooth cantilevered masses of modernism. Wright also seems to have captured not only a continuity with nature but also a kind of temporal continuity. Falling Water was built in 1935 and yet it could have been built a thousand years ago by some ancient civilization or some time in the 23rd century by an as yet unborn generation of architects.

Wright himself probably best described it when he wrote; "Fallingwater is a great blessing -one of the great blessings to be experienced here on earth. I think nothing yet ever equalled the coordination, sympathic expression of the great principle of repose where forest and stream and rock and all the elements of structure are combined so quietly that really you listen not to any noise whatsoever although the music of the stream is there. But you listen to Fallingwater the way you listen to the quiet of the country ..."

Wright also took the organic architecture concept one step further by developing designs which, just like the native American adobe architecture, were to be built from natural earth. During the Depression Wright developed a public works project for the construction of a whole community of 80 earth-built homes. Sadly, the project was interrupted by WWII. Today, there are many architects of the so called Prairie School who claim to employ Wright's organic architecture but who often seem to be merely parroting Wright's designs rather than actually employing the principles he cultivated. Consequently, Wright's version of the organic architecture concept seems to be slowly fading away into the noise of architectural fashion.

The chief limitation of Wright's organic architecture dirives from the fact that his work was by and large limited to large scale commercial and municipal works and the homes of the wealthy. The Prairie School did spread the Wright architectural style but most Prairie School architects would concentrate on the same types of projects. This is understandable considering the richness of materials and sophistication of craftsmenship the typical Wright design demanded. Few middle-class families could afford such things, then or now. Consequently, Wright's organic architecture never did become the mainstream indigenous American architecture he had intended. To be fair, Wright did in fact develop a small series of moderate-cost single family home designs he referred to as Usonian Homes which have had some influence on contemporary suburban architecture but by the time Wright created them America had already embarked on the pursuit of total suburbanization driven by corporate real estate speculation based on mass-produced housing. Wright's labor and talent intensive organic architecture was not compatible with the needs of mass-production. American suburbia was no longer about creating communities of homes but rather masses of appliances you lived in. Wright attempted to counter this with concepts for planned communities that could economize on organic housing approaches but this was largely viewed as the same type of utopian dreaming common to modernist architects and thus few of these plans came to fruition.

Another rather ironic problem common to Wright's organic designs was a failure of the modern materials he used to cope with the natural elements. His preference for flat roofs and large terraces ocassionally resulted in serious leaking problems due to the limitations of pre-war concrete technology. Falling Water itself was plagued by leaks, though the problem was partly exacerbated by some mistakes in the original construction and by delayed maintenance by the Kaufman family who originally owned the home.