The issue I shall address in this chapter is what kinds of duties we have towards living organisms, animals (including pets) and human beings. I shall defend the view that all (and only organisms) have moral standing, because of their intrinsic value - a view known as biocentric individualism - but that we can also have duties that refer to ecosystems, as well as species. While I reject the view that the intrinsic value of different individuals or different kinds of entities can be quantified and compared on a single scale, I suggest that there are a varying number of "dimensions of value" possessed by different kinds of organisms. I apply the notion of "basic goods" (popular in natural law theories of ethics) in my discussion of different kinds of organisms, to derive a rough list of basic goods for organisms without minds, sentient animals and human beings. I then identify these basic goods with the dimensions of intrinsic value, and attempt to distinguish the kinds of duties we have to different categories of organisms. Lastly, I attempt to delineate as precisely as possible which duties we owe to which organisms in these categories, and defend the view that the moral status of an organism depends not on its current states or even its capacities, but on its telos, which is grounded in the genetic information which supports the range of functions and pursuits that a typical member of that species is capable of engaging in.

For the purposes of this discussion, I intend to employ the following definition of the term "moral standing":

What is moral standing? ... [A]n individual has moral standing for us if, when making moral decisions, we feel we ought to take that individual's welfare into account for the individual's own sake and not merely for our benefit or someone else's benefit (Santa Clara University, 1991).

In chapter 1, I argued that all living things, and only living things, have a welfare of their own. I made a sharp distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic finality, and defended the view that living things, unlike man-made artifacts, are not good in a merely instrumental sense, but have a good of their own (or telos). I also argued that for non-sentient organisms, the fulfilment of biological functions is in their interests, irrespective of their being able to take an interest in their fulfilment. Finally, I argued that the notion of "doing good" or "acting morally" is more logically construed as acting in an individual's interests (i.e. promoting its welfare), rather than satisfying its desires for the objects it takes an interest in, as the former is by definition good for the individual, whereas the latter may not be. I proposed that the proper sphere of moral action is the promotion of the welfare of individuals (i.e. acting in their interests).

Varner (1998) distinguishes three ethical standpoints one might adopt towards the interests of individuals: anthropocentrism (the view that only human beings have moral standing or intrinsic value), animal welfare and animal rights views (the view that all and only sentient entities have moral standing or intrinsic value), and biocentric individualism (the view that all (and only?) living organisms have moral standing or intrinsic value). The first two views ascribe value to living things only insofar as they serve the interests of rational human agents or sentient beings. In chapter 1, it was argued that these views are arbitrarily narrow, as they overlook the biological interests of non-sentient beings. If one acknowledges these interests, it follows that anything with a welfare of its own is an appropriate object of moral concern, which implies that all organisms have moral standing. Each and every living thing matters in its own right. Insofar as I espouse this view, I am, like Varner, a biocentric individualist.

The position I have adopted here has obvious affinities to that of Paul Taylor (1986), who has argued that each living organism has "inherent worth" because it is a "teleological centre of life", i.e. a unified system of goal-oriented activities, whose aim is the preservation and well-being of that organism.

Taylor's position has been criticised (Brennan and Lo, 2002) for trying to derive a moral prescription from a biological description of an organism's flourishing. I suggest that this "is-ought" gap can be filled if we assume that the notion of "doing good" or acting morally has some content (the notion is not, after all, a meaningless one), and then ask ourselves what it might be. All ethical argumentation has to start somewhere, and we might take as a point of departure the principle that acting morally requires one to advert to one's own good and that of other individuals. Since it has been argued that interests rather than desires per se are a reliable indicator of an individual's good, we may conclude that one is morally required to respect the interests of an individual, including its biological interests.

My ethical position can also be described vis-a-vis Naess's (1989) distinction between shallow and deep ecology: a shallow ecologist is someone whose concerns are limited to his/her fellow human beings, while a deep ecologist has an attitude of "respect for nature" in its own right. My contention that organisms have a good of their own puts me in the latter camp. The first principle of Naess's Deep Ecology Platform, encapsulates this position:

The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves... independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

Table 5.1 - The Deep Ecology Platform

(Arne Naess, "Ecology, Community and Lifestyle", Cambridge, 1989, CUP, p. 29.)

|

1. The flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth has intrinsic value. The value of non-human life forms is independent of the usefulness these may have for narrow human purposes. 2. Richness and diversity of life forms are values in themselves and contribute to the flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth. 3. Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs. 4. Present human interference with the non-human world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening. 5. The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of non-human life requires such a decrease. 6. Significant change of life conditions for the better requires change in policies. These affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. 7. The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of intrinsic value) rather than adhering to a high standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great. 8. Those who subscribe to the forgoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to participate in the attempt to implement the necessary changes. |

Can we compare the intrinsic value of organisms?

While Naess is right to affirm the intrinsic value of all life-forms, this need not imply that their intrinsic value is quantitatively equal. Indeed, I would argue that the very notion that we can quantify the intrinsic value of different life-forms and compare them on a single sliding scale is a misguided one. I therefore cannot endorse either Paul Taylor's (1986) assertion that all individuals that are teleological-centres-of-life have equal "inherent worth" (his term), or Robin Attfield's (1987) claim that while all living things have intrinsic value, some (e.g. persons) possess it to a greater degree. Instead, I shall argue below that living things possess "dimensions" of intrinsic value, some of which are common to all life-forms, others unique to sentient animals and others unique to human beings.

The notion of a sliding scale of intrinsic value is profoundly morally misleading. First, it is inconsistent to affirm that all life-forms have intrinsic value, while arguing that the ends of "less valuable" life-forms are completely subordinate to those of "more valuable" ones. The complete subordination of less important entities to more important ones is unproblematic, only if the former possess purely instrumental value, which is a (though by no means the only) variety of extrinsic value. Beings possessing merely extrinsic value are important only in a derivative or parasitic sense, and entities possessing instrumental value can be regarded purely as a means to a greater end. Intrinsic value has a different kind of moral logic: anything possessing it, in whatever way or to whatever degree, matters in its own right. As such, it has at least a prima facie entitlement to be left alone and not be sacrificed to any individual's ends. To say that life-forms with lesser "inherent worth" are completely subordinate to those with greater inherent worth is to say that the former are not intrinsically valuable.

To make this point clearer, it might help to consider the following thought experiment. Imagine that intelligent beings from Vega who are as far ahead of us mentally as we are ahead of fish, come to visit our Earth. If these beings have an unforeseen accident that destroys the food they brought along for their trip, are they then morally entitled to eat human beings, if no other animals prove to be palatable?

Second, absolute comparisons of the intrinsic value of living things are pointless in the real world, where parasitism, predation and competition for scarce resources are rife, and "higher" and "lower" life-forms routinely kill each other. When the interests of two living things inevitably conflict, each has to put itself first or die. Self-preference is thus a practical requirement of life for all organisms. The logic of self-interest makes nonsense of any absolute comparisons of value, whether they affirm equality (A = B, but A may act as if A > B) or inequality (A may act as if A > B, and B may act as if B > A). These idle comparisons divert attention from the substantive ethical question (to be addressed in the following chapter): what kinds of self-preference are permissible for moral agents, who are aware that all living things possess a good of their own?

Deficiencies of holism

So far, I have not addressed the question of whether individuals alone have moral standing, or whether ecosystems, or even the environment-as-a-whole (air, land and water, as well as the organisms that live in them), could also have moral standing - a position Varner (1998) describes as environmental holism.

Varner (1998, chapter 1) attacks holism on several grounds, arguing that environmental holists have failed to adequately explain how an ecosystem can have intrinsic value or moral standing. In the first place, he argues, we cannot feel sympathy for it, as it is not a sentient individual. A community of sentient beings may also be an appropriate object of moral sentiments (e.g. patriotism), but an ecosystem is not such a community. An entity can also possess moral standing simply because it can be described as flourishing and healthy, but here the challenge is to provide a non-reductive account of the health of an ecosystem. Finally, other criteria which have been proposed for ecosystems (e.g. Leopold's famous "integrity, stability and beauty") do not constitute health as such, and are not sufficient criteria for something's having moral standing. Lots of things have beauty, integrity and stability (or a capacity for self-renewal), yet we do not regard them as morally significant on that account.

Pace Varner, I would argue that a non-reductive measure of the health of an ecosystem can be formulated, even though the flourishing itself is derivative upon that of the living organisms whose interactions constitute the ecosystem. The living things (or "nodes") which are connected within an ecosystem are interdependent organisms whose ties may be strengthened or weakened. I propose that one way in which we could measure the flourishing of an ecosystem is by counting the number of "linkages" (dependent relationships) between its "nodes" (different species that exist within an ecosystem). We could say that an ecosystem thrives when the rate at which new interactions (or "linkages") are being formed is greater than or equal to the rate at which they are being destroyed.

Human beings can thus benefit or harm an ecosystem by their actions. They can also defend an ecosystem. Does this make holism a viable position?

Pure holism

Varner (1998) distinguishes between two kinds of holism: pure holism, which ascribes moral value only to ecosystems and not to individuals, and pluralistic holism, which ascribes moral value to ecosystems as well as individual organisms. I maintain that pure holism is misconceived, because ecosystems do not possess the kind of unity which warrants the ascription of interests to them, whereas living things do. My argument can be summarised thus:

1. A necessary condition for an entity to have a good of its own is that it possess: (i) a master program which codes for the structure and functionality of the parts; (ii) a nested hierarchy of organisation; and (iii) embedded functionality, where entire repertoire of functionality of the parts is "dedicated" to supporting the functionality of the whole unit which they comprise. (Argued in chapter one.)2. Individual organisms possess this kind of top-down functionality; ecosystems do not. Specifically, ecosystems fail conditions (i) and (iii).

3. Therefore, while individual organisms can have a good of their own, ecosystems cannot. Lacking a good of their own, nothing can be said to be in their interests.

4. A sufficient condition for ascribing interests to an organism is that the attainment of its ends can be understood as good for it in non-relative terms (i.e. in its own right), without reference to some larger system.

5. An individual organism has ends (e.g. nutrition and growth) whose realisation can be understood to be good for it, without reference to some "larger context" (such as the state of the environment or ecosystem in which the organism exists).

6. Therefore, interests can be meaningfully ascribed to an individual organism in absolute rather than relative terms.

In support of step (2) of my argument:

Ecosystems possess nothing like the hierarchical regulation of a master program. An ecosystem is a loose, flexible federation of organisms, with varying degrees of interdependence. The system does not regulate the members from above; rather, the members loosely regulate one another. Additionally, most of the regulation mechanisms are replaceable over time; the number of "keystone species" whose removal triggers ecological breakdown is relatively small.

Additionally, the living things whose interactions make up an ecosystem are not inherently dedicated to its continuation, as the parts of an organism are dedicated to its well-being. (Strictly speaking, the parts of an ecosystem are not organisms, but the linkages between them. I envisage an ecosystem as a totality of biological facts, not biological objects, in the terminology of Wittgenstein's Tractatus.)

The conceptual mistake of pure holism, I would suggest, is that it envisages the flourishing of an organism as good in purely relative terms: organisms are regarded merely as cogs in the greater Wheel (or Circle) of Life, or as cells in the body of Mother Nature. Such a view overlooks the fact that an organism is not "dedicated" to its ecosystem in the way cogs are related to wheels, or cells to bodies. Whereas the functionality of a cog subserves the smooth operation of the wheel in a hierarchical part-whole relationship (like that between the parts of the body and the whole), an ecosystem is simply a network of systemic relationships between living things, and hence the milieu within which they exist. Unlike the wheel, its flourishing is conceptually derivative upon, and not prior to, that of its parts. For a living thing, the whole is conceptually prior to its parts; for an ecosystem, it is the other way round.

Pure holism nevertheless contains a kernel of truth. Although the goodness of an organism's flourishing is intrinsic, and not merely conditional on the flourishing of its ecosystem, it is also true that the flourishing of most organisms is inseparable from that of their local environment, within which they are "embedded" (Taylor, 1999, p. 131). (There are obvious exceptions to this rule: human beings, who can transform their own environment; introduced pests such as the cane toad; transportable organisms such as microbes, that can survive in an unfriendly environment by becoming dormant; and parasites, which survive within their hosts.) In particular, an organism obtains many of its needs (e.g. food) from the other organisms in its ecosystem. Finally, I would argue that an organism has a long-term biological interest in leaving as many descendants as possible, which (in typical cases) it cannot do if its flourishing jeopardises the continuation of its ecosystem. The long-term interests of individual organisms constitute a sufficient reason to protect ecosystems, without the need to ascribe special rights to ecosystems or the environment.

Pluralistic holism: the need for environmental impact statements

As regards pluralistic holism, while we may allow that ecosystems have some kind of moral standing, insofar as they have a kind of flourishing and can benefit or be harmed, the crucial ethical question as whether this moral standing is prior to, or derivative upon, that of the individuals whose interactions constitute it. It should be clear from the preceding discussion that the latter answer is correct. Since ecosystems do not do any extra ethical "work", biocentric individualism is a more parsimonious hypothesis.

Nevertheless, it can sometimes be more convenient to consider the morality of an action which will impact on various organisms, in terms of the benefits and harms to the ecosystem as a whole, rather than the benefits or harms to the individual members of the ecosystem.

One gain from considering the overall environmental impact of a course of action is that it informs us whether the action is sustainable in the long run. If it is not, then the fact that it benefits a particular organism in the short run does not legitimate it. As we have seen, individual organisms also have long-term interests in the continuation of their own lineages, and the thriving of most organisms is tied to that of their ecosystems. Hence an adverse long-term ecological impact of a proposed human activity is against the interests of most of the organisms within that ecosystem. The long-term ecological sustainability of a course of action is thus a convenient way of expressing the combined interests of the organisms which inhabit that ecosystem. In chapter six, it will be argued that human beings have the right to defend ecosystems against human activities that cause unsustainable damage.

Another benefit of evaluating the environmental impact of a proposed action is that we can compare it with that of another proposed action, and choose (ceteris paribus) the one that causes the least overall disruption.

It was argued in chapter 1 that every organism has a flourishing of its own. As Paul Taylor (1986) puts it, each organism matters because it is a teleological centre of life - that is, "a unified system of goal-oriented activities, the aim of which is the preservation and well-being of the organism ... whether or not the animal or plant in question is conscious" (cited in Taylor, A., 1999, p. 126). This line of thinking, which I endorse, implies that the primary reason why harming a living thing is wrong is because it thwarts the realisation of its telos. In this respect, it makes no difference whether the organism is an animal or plant: the fact that it has a flourishing of its own means that it has its own interests.

If we accept the principle (argued for above) that the interests of individuals command the respect of moral agents, it follows that acting against the interests of another individual is a prima facie morally wrong, and requires ethical justification. Of course, an act which is prima facie morally wrong may well be morally justifiable; the point is that its justifiability has to be argued for, and that the interests of others must at least be taken into account, in one's moral deliberations. Since all organisms have interests, it follows that it is a prima facie moral wrong to do anything detrimental to the interests of any living organism.

O'Neill (1992) questions the idea that harming a living thing is even a prima facie wrong, arguing that there are some things that simply should not flourish:

That Y is a good of X does not entail that Y should be realized unless we have a prior reason for believing that X is the sort of thing whose good ought to be promoted...[T]here are some entities whose flourishing simply should not enter into any [utilitarian] calculations - the flourishing of... viruses for example. It is not the case that the goods of viruses should count, even just a very small amount. There is no reason why these goods should count at all as ends in themselves...(O'Neill, p.117).

Davison (1999) counters that we cannot judge the intrinsic good of an entity by its effects on human beings. Instead, he asks us to compare a world in which there are no viruses and no living things at all to a world in which there are viruses [dormant, one presumes] but no other living things at all. Surely, the latter world would be a better one: it would possess a richness that the inanimate world lacked. It is perfectly consistent, I would suggest, to appreciate the unity, complexity and intrinsic finality of a lethal organism, even while seeking to eradicate it out of legitimate self-interest.

The example of viruses shows that our duty to respect the interests of other organisms is massively defeasible. This duty cannot be a moral absolute; if it were, we would be obliged to let other things flourish to our detriment, and we would not be permitted to use them as sustenance. It would be immoral to combat AIDS or to harvest crops in order to eat the produce. An unconditional obligation to respect the telos of other life-forms would be ethically suicidal. In the following chapter, I shall argue that a principle of self-preference, rightly understood, is ethically justifiable, morally rigorous and compatible with human flourishing.

Earlier, I criticised the enterprise of comparing the intrinsic value of two living things. There may, however, be several irreducibly distinct ways in which a living thing is intrinsically valuable. We might say that it has several "dimensions of value". One living thing could then be said to have more dimensions of value than another. Of course, the proposition "A has more dimensions of intrinsic value than B" in no way entails the conclusion "B may be sacrificed for the sake of A" but it could well imply that C (a moral agent) has a different set of duties to A than to B, and perhaps that C's duty not to harm A is stronger than C's duty not to harm B. It is only in this qualified moral sense that one might speak of a "hierarchy" of life-forms.

So far, we have discussed only the biological interests of organisms, but as we saw in chapter 1, there are other kinds of interests: animals with minds may take an interest (as opposed to merely having an interest) in getting what they want. Animals with wants therefore have "psychological" ends (objects of desire) which other living creatures do not. Does this mean that our duties to animals somehow out-rank our duties to other creatures? Should animals count for more in our moral deliberations?

Is there a hierarchy of life-forms?

Varner (1998) has argued for what he calls a "hierarchy of life forms: human beings are generally more important than other animals that have desires..., and these in turn are more important than organisms without desires" (1998, pp. 95-96). Varner engages in an extended justification for the second part of his claim (animals with desires are more important than organisms without desires). The nub of his case is that an animal's capacity to have desires supervenes upon the satisfaction of innumerable biological interests that it has. For instance, "I could not continue to form and satisfy desires without adequate nutrition, without my gastrointestinal tract, my heart and lungs, my limbic system, and so on all continuing to function" (1998, p. 94).

According to Varner, the life of a sentient animal requires the satisfaction of a large, "indeterminate" (1998, p. 94) number of desires over the course of its existence, in addition to the satisfaction of its "myriad" (1998, p. 94) biological interests which it shares with non-sentient creatures. From this, he derives an ethical principle:

(P1) Generally speaking, the death of an entity that has desires is a worse thing than the death of an entity that does not (1998, p. 94).

Varner's argument is a little unclear at this point. He could mean that sentient animals have interests of a kind that other creatures do not (true, but insufficient to establish P1), or that ceteris paribus, animals have (numerically) more interests than other creatures, as they have desires as well. Even if we set aside the difficulty of counting interests, as well as the objection that certain large organisms without desires are likely to have numerically more interests than some small organisms that have desires, the point remains that if one's moral status depends on how many interests one has, then the moral difference between organisms with and without desires would appear to be relatively slight, as the number of biological interests that must be satisfied for an animal to be able to formulate even a single, momentary desire is vast - orders of magnitude larger than the number of desires it might have over a lifetime.

Additionally, Varner complicates his case by trying to argue for two kinds of priority at the same time: that of desires over biological interests (1998, pp. 79, 95) and that of organisms with desires over those without (1998, pp. 78, 95). The former, I would suggest, is redundant; in order to establish a moral hierarchy, he only needs the latter kind of priority. In any case, the supervenience of desires upon biological interests (1998, p. 94) does not establish that desires are more important than biological interests.

One might invoke Varner's point about supervenience to defend the priority of organisms with minds, on purely biological grounds. One could argue that an organism with a mind requires a body that is neurologically (if not computationally - see chapter 2) more complex than that of a mindless organism. If we compare a multicellular animal with a nervous system and a brain with a unicellular bacterium, the former could be said to have more "levels" of dedicated functionality, and hence a richer kind of unity, than the latter. One might then judge the animal to be worthy of greater respect than the bacterium, and view the death of the animal as a greater tragedy than that of the bacterium (Varner's principle P1).

However, the biologically grounded moral hierarchy proposed here would differ from that used by most people in several important respects: killing a multicellular but mindless animal (e.g. a jellyfish or possibly a flatworm) would be nearly as bad as killing an animal with a mind (e.g. an insect), but somewhat worse than killing a plant, which would be considerably worse than killing a single-celled, eukaryotic amoeba, which would be much worse than killing a prokaryotic bacterium.

Additionally, it is not clear why the proposition "A has more levels of dedicated functionality than B" should imply that "A is worthy of more respect than B". The mere fact that an entity possesses dedicated functionality is a morally relevant characteristic, insofar as it is a necessary condition for the morally significant property of being alive. However, it does not follow that the number of layers of functionality matters morally.

Nevertheless, Varner's book highlights important features of desires which, I shall argue, explain why the wrongful killing of sentient animals is worse than the wrongful killing of other organisms: desires (i) supervene upon biological interests (1998, p. 94), and (ii) often promote biological interests, yet (iii) the object of a desire is not always a biological good - indeed, an animal may even desire something that is biologically harmful to it (1998, p. 60). Point (i) establishes that biological interests are the platform which make desires possible; (ii) suggests one criterion for ascertaining whether the object of an animal's desire is objectively good (viz. Does it promote the animal's biological well-being?), and (iii) hints at a diversity of ends that are independent of the animal's biological well-being. Indeed, it is this diversity of ends or goods pursued which augments the wrongfulness of killing an animal, as it is being robbed of the opportunity to pursue several kinds of goods, not just biological ones.

Basic animal goods

In chapter 2, it was argued that animals with minds are agents with beliefs and desires relating to their ends, who exercise self-control as they try to attain their ends. In chapter 3, the emotional life of these animals was described. What concerns us here is that animals, as beings that try to satisfy their desires, are capable of pursuing a variety of ends that organisms without desires cannot pursue.

In chapter 2, we looked at Beisecker's (1999) argument that these animals, as holders of expectations, exhibit "a normativity, or goal-directedness, that is independent of, and occasionally might even run contrary to, their biologically determined natural purposes". Now, the satisfaction of a want, unlike a biological interest, may not be beneficial to the animal: an animal may crave drugs, for instance. However, any goal pursued by an animal which serves a biological function is unquestionably legitimate. Among the goals desired by animals, we can discern certain categories of good, whose realisation contributes to the well-being or thriving of the animal, in a way that can be discerned objectively (e.g. by a veterinarian or an ethologist). We might say that it is "proper" for the animal to pursue these ends for their own sake, although their biological usefulness may be direct or indirect. The following is a rough (but not necessarily exhaustive) list of the categories of "goods" legitimately pursued by an animal for their own sake, together with their biological justification, which serves to legitimate them. It goes without saying that the subjective reason why an animal pursues a good is quite independent of its biological function, or as Masson and McCarthy put it, "the fact that a behavior functions to serve survival need not mean that that is why it is done" (1996, p. 28). I shall refer to categories of goods pursued by animals as basic animal goods:

It should be noted that phenomenal consciousness is not needed to realise most of these basic animal goods. As we saw in chapter two, even animals with minimal minds can pursue practical goals and acquire practical (non-conscious) knowledge when they learn how to fine-tune their moves to attain their goals. The ethical significance of phenomenal consciousness in a basic goods framework is thus relatively minor: having a minimal mind makes much more of a difference.

The satisfaction of wants belonging to these categories of basic animal good can be said to contribute to the animal's thriving, and thereby promote its telos, just as the thwarting of these wants causes a "failure to thrive". This thriving occurs not only on a biological level but also on a mental level: Masson and McCarthy (1996, p. 30) use the word funktionslust to describe the delight taken by an animal in doing what it does well (e.g. the pleasure taken by a cat in climbing trees). For an animal with a mind, then, its telos includes not only the satisfaction of its biological interests, but also the satisfaction of those wants which belong to some category of "proper" pursuits.

What I am suggesting is that the killing of animals is prima facie immoral, not merely because it thwarts biological ends (as is the case when a plant or bacterium is killed), but also because it thwarts the realisation of basic animal goods. Basic animal goods add extra "dimensions" to the wrongfulness of killing an animal, because the animal is robbed of more than biological thriving.

If we compare the wrongful killing of an animal with the wrongful killing an organism without a mind, we can detect certain similar themes - a life rudely thwarted, goals that will never be realised, interests cruelly doomed. Here, the doomed interests are purely biological interests, for mindless organisms. However, there are other features of wrongful killing that are unique to animals with minds: pursuits nipped in the bud, attempts that will never be made, deeds that will never be done, sights that will never be seen, feelings (love, anger, desire, fear) that will never be felt, and (in the case of phenomenologically conscious animals) pleasures that will never be experienced or remembered, and (for social animals) friendships that will never be formed. Here, the foregone mental states and acts relate not only to biological ends, but to the entire suite of basic animal goods.

If the notion of "dimensions of wrongness" is a valid one, we can derive a modest ethical principle (the Wrongful Killing of Animals principle, or WKA):

The wrongful killing of an animal that has desires is a greater moral evil than the wrongful killing of an organism without a mind.

One could also formulate a similar claim about wrongful injury.

The occurrence of agency in animals does not imply that the killing of animals is necessarily wrong, but it does provide us with additional prima facie grounds for not taking their lives.

Are we then obliged to become vegetarians? It should be borne in mind that killing animals in order to eat is inescapable in the real world: even a vegetarian lifestyle requires us to kill legions of pests to protect our crops. What WKA implies is that we have a strong prima facie obligation to kill as few animals as we can in the process of obtaining our food. In industrialised countries, that means that a vegetarian lifestyle is preferable, and a vegan lifestyle is ideal, if practicable. In extreme climates, or remote locations, only a hunting and gathering lifestyle may be feasible.

Animals are others whose wishes and feelings must be respected

So far, we have highlighted animals' capacity to pursue different categories of ends as a reason to place them in a special moral category, but we have said nothing about their wishes, likes and dislikes. Does animals' possession of desires and/or phenomenally conscious feelings put them in a special moral category?

Mary Midgley (1984, pp. 91 ff.) has argued that the Golden Rule (which she cites as "treat others as you would wish them to treat you") comes into play when we are dealing with animals who have wishes of their own. However, the Golden Rule can be construed in two different ways. Midgley construes it, reasonably, as an injunction to respect the (conscious) wishes of others. Alternatively, one might construe it as a prohibition against harming others - i.e. doing things to others that one would not like done to oneself. Confucius' minimalistic version of the Golden Rule - "What you do not like when done to yourself, do not do unto others" - can be construed thus. Likewise, the Mahabharata (18.113.8) simply states, "One should never do that to another which one regards as injurious to one's own self." These versions of the Golden Rule do not stipulate that an individual must have wishes of its own to qualify as an "other". They could apply to any living thing that can be injured or have bad things done to it, as many bad things that are done to plants - being sawn in half, having body parts ripped off - are things that one would not like to have done to oneself. If one adopts a minimalistic "no-harm" version of the Golden Rule, then animals are not in a special moral kingdom.

Midgley acknowledges that we have some duties to all kinds of living things, but argues strongly that conscious beings belong in a special moral category:

Sentience is important because of the very dramatic difference it makes in the kind of needs which creatures have, and the kind of harm which can be done to them... You can express it from the point of view of the creature itself, saying that "since it is conscious, injury and extinction will be bad for it". Or you can put it more abstractly, saying something like "since it is conscious, it has value; if it is injured or extinguished, the world will be the poorer" (1984, pp. 90, 93).However, the central argument of this thesis is that injury and extinction are bad for any living thing, since it has a good of its own. The intrinsic value of a living thing does not depend on its being conscious, but on its being alive. The world would be a poorer place without any organism, even a virus.

My biocentric position in no way implies that sentience should count for nothing in our moral considerations. Indeed, if my argument regarding basic animal goods is correct, there are dimensions of intrinsic value that can only be possessed by phenomenally conscious beings. While Midgley is surely wrong in claiming that the capacity to feel is necessary for an individual to have value, an individual's possession of a capacity to feel certainly counts as an additional reason why it should matter morally.

Until now, I have only discussed the ethical implications of a minimalistic version of the Golden Rule: do not harm others. However, Midgley's stronger construal of the Golden Rule as an injunction to respect the wishes of others is an equally valid interpretation, which carries the ethical implication that feelings do indeed count for something. The two versions of the Golden Rule ground two kinds of duties: a prima facie obligation (owed to all organisms) to refrain from harming them, as well as an obligation (owed only to sentient animals) to respect their wishes. With regard to the latter obligation, three questions are pertinent: which wishes should we respect, how far should we respect them, and how binding is our obligation?

Obviously, the Golden Rule does not require us to advert to all kinds of wishes: one should not supply drugs to an animal that craves them. However, I would suggest that the Golden Rule does require us to advert to an animal's wishes, when they fall into one of the telos-promoting categories (basic animal goods) listed above, simply because their fulfilment is unambiguously good for the animal, as well as being psychologically rewarding.

By "advert", I do not mean "assist": that would impose impossibly burdensome obligations upon us. Additionally, positive obligations to assist animals would place us in an ethical dilemma: should we help predators in their search for prey, whose flesh they crave and need, or should we protect their prey from the predators they fear? One way to escape this dilemma would be to limit our moral obligations to negative ones. In that case, both the stronger and weaker versions of the Golden Rule would be construed as negative injunctions: "Do not thwart animals' telos-promoting desires" and "What you do not like when done to yourself, do not do unto others", respectively.

It goes without saying that our (negative) obligations to respect animals' wishes are prima facie rather than absolute: obviously, we are entitled to destroy animals which want to do things that kill us or make us ill (e.g. mosquitoes that cause malaria). I shall discuss the limits to our obligations to animals in the next chapter.

Our obligation not to be cruel to animals

Because animals with mental states can suffer, we have an obligation not to be cruel to them. This is true, regardless of whether we envisage cruelty as the deliberate infliction of pain (Midgley, 1984) or the deliberate frustration of animals' first-order desires (Carruthers, 1999).

Midgley's (1984) ethical position vis-a-vis cruelty to animals is grounded in the Golden Rule, applied to beings with "experiences ... like our own" (1984, p. 91). The proper response to a small child found tormenting an animal is "You wouldn't like that done to you" (1984, p. 91) - an explicit appeal to the child's sense of sympathy. By contrast, Carruthers (1999) denies that animals experience subjective pain, and argues that when we harm animals, the chief wrong done is not the pain caused but the frustration of their first-order desires. Despite my disagreement with Carruthers' bizarre denial of animal subjectivity, I find his criticism of the utilitarian ethic to be insightful, insofar as it characterises suffering animals as frustrated agents, although I would query his claim that the desires of animals are of paramount importance. As I have argued, harming animals (and organisms generally) is wrong because it frustrates their attainment of their natural ends (including desired ends), rather than their desires per se: we saw in chapter 1 that some of the desires of animals may even run counter to their interests. In any case, lack of time or relevant information prevents animals from being able to form desires for everything that is in their interests.

Carruthers' (1999) reinterpretation of animal suffering is a salutary one, as it broadens our moral horizons. Instead of simply focusing on the minimisation of subjective pain in animals, we should also try to minimise our interference with animals' exercise of their faculties, and maximise their opportunities for what Masson and McCarthy (1996, p. 30) refer to as funktionslust - an animal's pleasure in doing what it does well.

Human taboos against cruelty to animals are long-standing: the Noachide code of Judaism, the Hindu Bhagavad Gita (13.27-28, 16.2) and the Dhammapada (paras. 129-130, 225, 405) (sayings of Buddha) all condemn the practice, and the new Catechism of the Catholic Church says of animals: "men (sic) owe them kindness" (para. 2416). I shall discuss in chapter 6 the question of whether our obligation not to treat animals cruelly is an absolute one. In the meantime, we can formulate an ethical minimum standard: the principle that the infliction of cruelty upon animals, as an end in itself, is unqualifiedly wrong. This follows from the fact that cruelty is an evil. To justify cruelty as an end-in-itself would imply the absurd consequence that one may delight in evil as such.

To sum up, we have established that there are legitimate, inter-related ethical grounds for believing that we have certain extra obligations to animals. These grounds include animals' capacity to pursue multiple basic animal goods as agents, their possession of feelings, especially wants or wishes, and their capacity to suffer pain and have their desires thwarted. Our obligations to animals with minimal minds and sentient animals collectively entail that: (i) the prima facie wrongness of killing (or injuring) an animal is greater than that of killing (or injuring) other organisms; (ii) we have a prima facie obligation to respect animals' feelings, and refrain from frustrating them in their pursuit of telos-promoting ends; and (iii) we may never inflict cruelty on animals as an end in itself.

Marginal animal cases

The term "marginal cases" is sometimes applied (e.g. Dombrowski, 1997) to humans lacking the capacities that are commonly thought to distinguish us from other animals. Here, I use the term "marginal animal cases" to refer to animals whose immaturity, genetic damage or physical injury precludes them (at least temporarily) from exercising agency or being sentient - e.g. animal embryos, anencephalic animals and decerebrated and permanently comatose animals. In Appendix A, I challenge the view that only sentient animals are morally significant, and defend an alternative view that marginal animal cases have the same moral status as their normal counterparts because they have the same nature - a concept I discussed in chapter one. More precisely, I argue that since an individual's telos determines its moral status, and each "marginal animal case" has a physically normal counterpart with the same telos, it follows that "marginal animal cases" have the same moral status as their normal counterparts. I discuss the implications of this view regarding our duties towards decerebrated animals.

In addition to our general duties to animals, there is an additional category of obligations that we have towards companion animals, simply because they are our friends. On the basis of the evidence presented in chapter 3 (Midgley, 1991) that people and their pets often have emotionally symbiotic relationships, I shall assume here that genuine friendship with some kinds of animals is a possibility.

Our obligations towards companion animals, with whom we share bonds of friendship, are especially strong if we have assumed the responsibility of caring for these animals. These obligations are much stronger than our obligations towards other animals: if they are our friends, we have a concern for their well-being, and if we are responsible for looking after them, we have made a commitment to promote their well-being. Thus we are not only required to refrain from hindering them in the pursuit of their proper ends, but also to offer them positive assistance in the pursuit of their ends, when needed. This positive obligation is however not an absolute one. For instance, one has no obligation - indeed, it would be wrong - to promote the welfare of a companion animal by putting an ecosystem at risk. One would also be justified in having one's pet put down if it endangered the health of a family member, and no-one else was willing to adopt it.

While owners of companion animals have the right to protect themselves (and others) from any dangers posed by their companion animals, I would argue that they may not harm, injure or kill their companion animals, simply in order to procure or promote their own good. Friends do not use each other like that. One might use a friend to promote one's own ends, but one may not harm a friend for one's own benefit. This has relevance for Regan's famous case (1988, pp. 285, 324-325) of the dog in the lifeboat. Since there can be bonds of genuine, reciprocal friendship between humans and dogs, my proposal would imply that if the dog is a pet, its owner may not throw it overboard, even to save his or her life, despite the fact that I consider the life of a dog (as a non-moral agent) to have fewer "dimensions of intrinsic value" than that of a human being. Likewise, if the dog's owner were starving, he/she may not eat the dog. (The situation is different with a non-companion animal, for reasons that will become apparent in the next chapter.)

Whether they are our friends or not, we have special obligations towards other human beings, on account of their unique telos. Among the goals desired by human beings, we can discern certain categories of good, whose realisation contributes to our well-being or thriving. These goods are said to be intrinsically valuable (properly desirable for their own sake), objective (in that their goodness is independent of the attitude of the subject pursuing them) and universal (good for everyone). These goods are commonly known as basic human goods. Unsurprisingly, different natural-law theorists have drawn up somewhat different lists of these goods. I have culled and re-arranged the following table of basic human goods from Murphy (2002), listing the goods by author and grouping them according to their shared category, to demonstrate their broad agreement:

Table 5.2 - Basic human goods, according to various authors

| Category of Human Good | Aquinas | Finnis 1980 | Grisez 1983 | Finnis 1996 | Chappell 1995 | Murphy 2001 | Gomez-Lobo 2002 |

| BIOLOGICAL GOODS | |||||||

| Life | Life | Life | Life and health | Life | Physical and mental health and harmony | Life | Life |

| Procreation | Procreation | Included in Life | Included in Life | The marital good | Included in Life? | Included in Life? | The family |

| HUMAN SOCIAL LIFE | |||||||

| Friendship | The social life | Friendship | Justice and friendship | Justice and friendship | Friendship | Friendship and community | Friendship |

| EVERYDAY PURSUITS | |||||||

| Practical reason | Rational conduct | Practical reasonableness | Practical reasonableness | Practical reasonableness | Reason, rationality and reasonableness | - | - |

| AREAS OF HUMAN ENDEAVOUR | |||||||

| Knowledge | Knowledge | Knowledge | Knowledge of truth | Knowledge of truth | Truth and the knowledge of it | Knowledge | Theoretical knowledge |

| Work | - | - | - | - | Achievements | Excellence in work | Work |

| Agency | - | - | - | - | Achievements | Excellence in agency | - |

| Play | - | Play | Playful activities | Playful activities | Achievements | Excellence in play | Play |

| ENJOYMENTS | |||||||

| Appreciation of beauty | - | Aesthetic appreciation | Appreciation of beauty | Appreciation of beauty | Aesthetic value | Aesthetic experience | Experience of beauty |

| Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | Pleasure and the avoidance of pain | Happiness | - |

| MORAL VIRTUES | |||||||

| Integrity | - | - | Authenticity | Authenticity | - | - | Integrity |

| Self-integration | - | - | Self-integration | Self-integration | - | - | - |

| Inner peace | - | - | - | - | Physical and mental health and harmony | Inner peace | - |

| Fairness | - | - | Justice and friendship | Justice and friendship | Fairness | - | - |

| THE TRANSCENDENT | |||||||

| Religion | - | Religion | Religion | Religion | - | Religion | - |

| OBJECTS OF HUMAN CONCERN | |||||||

| People | - | - | - | - | People | - | - |

| The natural world | - | - | - | - | The natural world | - | - |

Chappell (1995) deserves special commendation for including in his list of basic human goods a good - the natural world - which liberates us from the moral hazards of excessive anthropocentrism. For my part, I suggest it would be more accurate to describe the care of living things and/or ecosystems as a basic human good. (Keeping the air, land and sea pollution-free could be regarded as indirectly taking care of living things.) The care of living things is good, because it promotes the welfare of things that possess intrinsic value. It is a human good, because human beings, unlike non-rational creatures, are capable of loving living things for their sheer aliveness, and the promotion of other creatures' telos is good per se. It is properly basic, because it is irreducible to the other human goods.

My reliance upon a natural-law tradition assumes that the concept of "nature", applied to humans and other animals, is a valid one - a notion that will be defended below. The key points that emerge from the table are that the list of basic human goods is much more extensive than the list of basic animal goods, and that there is broad agreement about its contents. (The list by Finnis (1980) is fairly representative.) Despite sentient animals' capacity for intentional agency and their rich emotional life, we saw in chapter 4 that there are no good grounds for supposing that any non-human animals possess moral agency. They pursue the good things of life, but they do not concern themselves with the question of what a good life is. They have some control over the means they use to attain their ends, but cannot question whether their pursuit of an end is worthwhile. In other words, basic human goods add extra "dimensions" to the wrongfulness of killing a human being, as compared with the wrongful killing of an animal, because the human being is robbed of much more.

This becomes apparent if we compare the monstrously immoral act of killing a human being with the cruel and barbarous act of gratuitously killing a phenomenally conscious animal (assuming that both acts of killing are wrongful). There are strong similarities between the two - a life rudely thwarted, goals that will never be realised, interests cruelly doomed, pursuits nipped in the bud, attempts that will never be made, deeds that will never be done, sights that will never be seen, pleasures that will never be experienced or remembered, and (for some animals) friendships that will never be formed - as well as other features unique to homicide: achievements (small or great) that will never be accomplished, discoveries that will never be made, artistic or scientific acts of creation that will never see the light of day, beauty that will never be enjoyed, lifetime plans rudely interrupted, kind and loving words and deeds that will never be said or done to other human beings, virtues that will never be cultivated, a blighted struggle to create a meaningful existence for oneself, a thwarted endeavour to make the world a better place, and the brutally truncated moral and spiritual drama of a life that was never allowed to unfold: the life of a unique and irreplaceable person. Because many of these human goods require a lifetime for their complete expression, it is only to be expected that terminating the life of a human being would be justifiable only for the gravest of reasons. Indeed, there is only one generally accepted moral ground that over-rides our obligation to refrain from harming other human beings: namely, the defence of innocent human life. Since the killing of a non-moral agent does not interrupt the "story of a life", it may be permissible in a wider range of circumstances. This explains why it may be morally justifiable to put down an animal carrying a highly contagious infection, or kill it for food when no alternatives are available, even though doing the same thing to a fellow human being would be wrong.

The argument from marginal human cases

Some of the basic human goods described above are (temporarily or permanently) out of reach for some human beings (so-called marginal cases, discussed in Dombrowski, 1997). Many animal liberationists employ what Dombrowski (1997) calls the argument from marginal cases to argue that there are no morally relevant differences between animals and human beings who are not moral agents: either because they are very young, severely intellectually disabled or permanently comatose.

In a similar vein, Regan (1988) defines "subjects-of-a-life" as mentally normal mammals aged one year or more.

It should be clear from my defence of the concept of "nature" in chapter one why I would regard this line of argument in defence of animals as profoundly mistaken: and I argue in Appendix B that we do both animals and marginal human cases a disservice by assimilating the former to the latter. Marginal human cases, I claim, have the same telos as their normal human counterparts. The telos of non-human animals is different, because it does not include ends that presuppose moral agency. I defend my argument from accusations that it is arbitrarily speciesist. I anticipate and respond to possible objections regarding the moral status of human-chimp hybrids and genetically engineered "super-chimps" with human capacities.

Can we have any duties towards a greater whole, such as an ecosystem, or the biosphere, or our natural environment? I would argue that we do not. The principal reason is that the flourishing of these systems is the wrong sort of flourishing to warrant the ascription of proper interests to them. We cannot speak of an entity having interests of its own unless the function and thriving of its parts are dedicated to that of the whole. While the organisms in an ecosystem are certainly inter-dependent, the inter-dependence is generally fairly loose, and they could hardly be described as dedicated to each other's (let alone the whole's) well-being. If ecosystems lack interests, there can be no obligations on our part towards them as such.

Nevertheless, we may have obligations relating to ecosystems, even if we do not have any obligations towards them. At a minimum, one has a strong prima facie obligation not to destroy or jeopardise an ecosystem, because it contains organisms which have moral standing, on account of their telos, and many of these organisms have a long-term interest in the continuation of their ecosystem, since they cannot leave behind any descendants without it. (Of course, one would have no obligation to preserve a "toxic" local ecosystem which constituted a threat to human beings - e.g. a swamp which bred mosquitoes that transmitted malaria.) Later, I shall argue that we are entitled (though not obliged) to defend an ecosystem against the depredations of organisms that are endangering it, even if doing so entails killing organisms. For instance, one may cull animals whose over-breeding is threatening a local community.

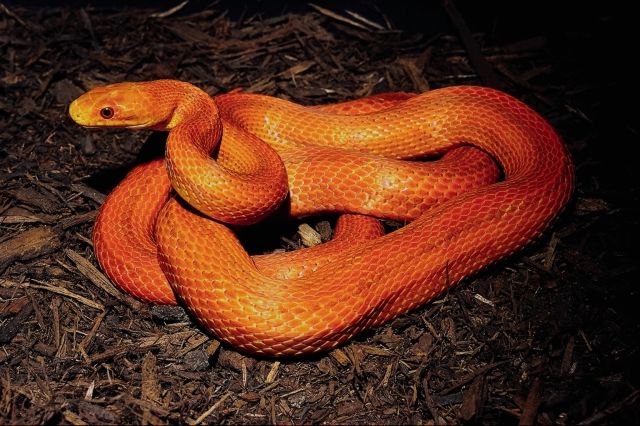

What about classes of living things, e.g. species? Once again, it is hard to see how we could have a duty to a class as such, since, like an ecosystem, it lacks proper interests. Could we, however, have special duties that pertain to species, rather than individuals? Passmore (1980) thinks not: he sees nothing inherently good about preserving biological diversity, and nothing intrinsically wrong with destroying a species. He asks whether we would condemn St. Patrick for driving the snakes out of Ireland. "And if to drive them out of Ireland is worthy of praise, should it not be equally praiseworthy to drive them out of the world?" (1980, p. 119).

Granting that there are some species that the rest-of-the-world would be better off without (e.g. mosquitoes that carry malaria) does not mean that we do not have a strong prima facie obligation to preserve a species that is under threat from our activities. Protecting a species is good, not just because it preserves individuals, but because it preserves a whole way of being alive - a unique kind of telos. The death of a species destroys that way of life forever. While such a loss represents a (non-moral) evil, the (intentional) causation of such a loss is a prima facie moral evil. The argument that species die out all the time in the natural world is irrelevant here; in the natural world, new species typically arise to take the place of old ones, but when humans kill species, this does not happen, so we leave the world a poorer place.

I shall argue in chapter six that it is sometimes permissible to harm individual organisms, in order to defend an ecosystem - not because we have duties to the ecosystem as such, but because its "welfare" encapsulates that of its living inhabitants, all of whom have a long-term interest in leaving descendants and most of whom cannot exist apart from their ecosystem. I shall propose a principle that stipulates conditions under which we may act in the justifiable defence of an ecosystem.