MEDICINE IN RENAISSANCE

The Renaissance revolutionized medical thought as

it did all scientific, artistic, and other intellectual activity. The

dissemination of knowledge was greatly aided by the development of printing.

Andreas Vesalius, born in Brussels, was a professor of anatomy in Padua, where he wrote De Humani

Corporis Fabrica (On the

Fabric of the Human Body, 1543). This work was the first accurate anatomy text

and included masterful illustrations that corrected errors of Galen. Vesalius

was the first of a line of superb anatomists at Padua, among whom were

Hieronymus Fabricius and Gabriel Fallopius.

L.Da Vinci’s drawing on a Japanese stamp

The Renaissance first influenced the

science of anatomy in the latter half of the 16th century. Modern anatomy began

with the publication in 1543 of the work of the Belgian anatomist Andreas

Vesalius. Before the publication of this classical

work anatomists had been so bound by tradition that the writings of authorities

of more than 1,000 years earlier, such as the Greek physician Galen, who had been restricted to the dissection of animals,

were accepted in lieu of actual observation. Vesalius and other Renaissance

anatomists, however, based their descriptions on their own observations of

human corpses, thus setting the pattern for subsequent study in anatomy.

Ambroise

Pare, a French physician, revolutionized surgery. He treated his patients

humanely, using ligatures to stop bleeding from vessels instead of cauterizing

them with boiling oil or hot instruments. Other men of this age included Aureolus Paracelsus, a Swiss physician who rejected

traditional schools of thought and advocated the use of such chemicals as laudanum

(a preparation of opium) in the treatment of disease. Girolamo

Fracastoro, an Italian physician, is best known for

his work on syphilis and other infectious diseases.

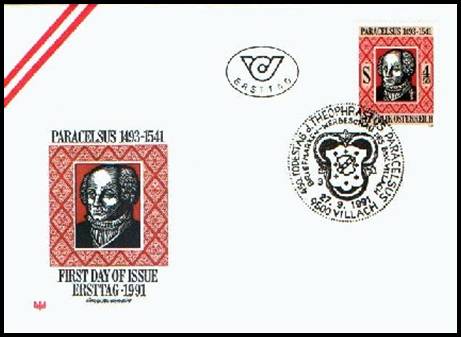

Philippus

Aureolus Paracelsus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim 1493 – 1541

German physician and

chemist, Quarrelsome and vitriolic, Paracelsus defied the medical tenets of his

time, asserting that diseases were caused by agents that were external to the

body and that they could be countered by chemical substances.

Born in Einsiedeln

(now in Switzerland), Paracelsus received a degree in medicine, possibly from the University of Vienna, and travelled widely in

search of alchemical knowledge, especially of mineralogy. He sharply criticized

the cherished belief of the Scholastics, derived from the writings of the Greek

physician Galen, that diseases were caused by an imbalance of bodily “humors”

or fluids, and that they would be cured by bloodletting and purging. Believing

instead that disease attacks from without, Paracelsus devised mineral remedies

with which he thought the body could defend itself. He identified the

characteristics of numerous diseases, such as goiter and syphilis, and used

ingredients such as sulphur and mercury compounds to

counter them. Many of his remedies were based on the belief that “like cures like ”, and in this respect he was a precursor of

homoeopathy. Although the writings of Paracelsus contained elements of magic,

his revolt against ancient medical precepts freed medical thinking, enabling it

to take a more scientific course.

FDC of Austrian post office for the 450th anniversary off his death

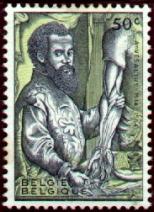

Andreas Vesalius 1514 – 1564

Belgian anatomist and

physician, whose dissections of the human body and description of his findings  helped to correct misconceptions prevailing since

ancient times and to lay the foundations of the modern science of anatomy.

helped to correct misconceptions prevailing since

ancient times and to lay the foundations of the modern science of anatomy.

Vesalius was born in Brussels. The son of a celebrated apothecary, he attended the University of Louvain and later the University of Paris, where he studied from 1533 to 1536. At the University of Paris he studied medicine and showed a special interest in

anatomy. Through further study at the University of Padua in 1537, Vesalius obtained his medical degree and an

appointment as a lecturer on surgery. During his continuing research, Vesalius

showed that the anatomical teachings from antiquity of the Graeco-Roman

physician Galen, then revered in medical schools, were based on dissections of

animals, even though they were intended to provide a guide to the structure of

the human body.

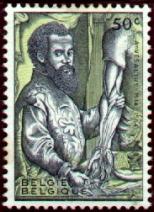

Vesalius went on to write an elaborate anatomical

work, De Humani Corporis

Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, 7 vols., 1543), which was based on his own dissections of

human corpses. The volumes were richly and carefully illustrated, with many of

the fine engravings rendered by Jan van Calcar, a

pupil of Titian. The most accurate and comprehensive anatomical textbook to

that date, it aroused heated dispute but helped lead to Vesalius's

appointment as physician in the imperial household of Charles V, Holy Roman

Emperor. After Charles abdicated, his son, Philip II, appointed Vesalius one of

his physicians in 1559. After several years at the imperial court in Madrid, Vesalius made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. On the voyage home in 1564, he died in a shipwreck off the Greek island of Zacynthos.

Vesalius went on to write an elaborate anatomical

work, De Humani Corporis

Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, 7 vols., 1543), which was based on his own dissections of

human corpses. The volumes were richly and carefully illustrated, with many of

the fine engravings rendered by Jan van Calcar, a

pupil of Titian. The most accurate and comprehensive anatomical textbook to

that date, it aroused heated dispute but helped lead to Vesalius's

appointment as physician in the imperial household of Charles V, Holy Roman

Emperor. After Charles abdicated, his son, Philip II, appointed Vesalius one of

his physicians in 1559. After several years at the imperial court in Madrid, Vesalius made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. On the voyage home in 1564, he died in a shipwreck off the Greek island of Zacynthos.

Ambroise Paré 1510 – 1590

French surgeon, born in Laval, whose great practical skills and humaneness

distinguished him from his contemporaries and made him famous throughout Europe. His successes in the French army as a military surgeon won him the post

of royal surgeon to King Henry II and Henry's successors, Francis II, Charles

IX, and Henry III. Paré established the use of

ligatures for binding arteries to prevent haemorrhage.

He did away with the practice of cauterizing wounds with boiling oil, improved

the treatment of fractures, and promoted the use of artificial limbs. Because

he had no formal education, Paré was the first

surgeon to describe his technical work in his native language rather than in

Latin; thus, his writings had a wide influence on the public as well as on

medical professionals.

French surgeon, born in Laval, whose great practical skills and humaneness

distinguished him from his contemporaries and made him famous throughout Europe. His successes in the French army as a military surgeon won him the post

of royal surgeon to King Henry II and Henry's successors, Francis II, Charles

IX, and Henry III. Paré established the use of

ligatures for binding arteries to prevent haemorrhage.

He did away with the practice of cauterizing wounds with boiling oil, improved

the treatment of fractures, and promoted the use of artificial limbs. Because

he had no formal education, Paré was the first

surgeon to describe his technical work in his native language rather than in

Latin; thus, his writings had a wide influence on the public as well as on

medical professionals.

helped to correct misconceptions prevailing since

ancient times and to lay the foundations of the modern science of anatomy.

helped to correct misconceptions prevailing since

ancient times and to lay the foundations of the modern science of anatomy.

Vesalius went on to write an elaborate anatomical

work, De Humani Corporis

Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, 7 vols., 1543), which was based on his own dissections of

human corpses. The volumes were richly and carefully illustrated, with many of

the fine engravings rendered by Jan van Calcar, a

pupil of Titian. The most accurate and comprehensive anatomical textbook to

that date, it aroused heated dispute but helped lead to Vesalius's

appointment as physician in the imperial household of Charles V, Holy Roman

Emperor. After Charles abdicated, his son, Philip II, appointed Vesalius one of

his physicians in 1559. After several years at the imperial court in

Vesalius went on to write an elaborate anatomical

work, De Humani Corporis

Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, 7 vols., 1543), which was based on his own dissections of

human corpses. The volumes were richly and carefully illustrated, with many of

the fine engravings rendered by Jan van Calcar, a

pupil of Titian. The most accurate and comprehensive anatomical textbook to

that date, it aroused heated dispute but helped lead to Vesalius's

appointment as physician in the imperial household of Charles V, Holy Roman

Emperor. After Charles abdicated, his son, Philip II, appointed Vesalius one of

his physicians in 1559. After several years at the imperial court in  French surgeon, born in

French surgeon, born in ![]()