| www.angelfire.com/dragon/letstry

cwave04 at yahoo dot com |  |

Introduction

A solenoid is just a coil of wire. You send a current through it, and a magnetic field develops. The field may be used for various purposes, the most popular of which is to pull a piece of iron (called the plunger). The performance of a solenoid depends on the following factors:-

The type of the wire.

The number of turns

The diameter of the coil

The length of the coil

The current through the coil

The power supply used

The resistance of the coil

-

the strength of the produced field

the heat dissipated

the size and weight of the coil.

Two fundamental relations

We shall make one simplifying assumption: the solenoid you are making is not more than 2 inches long. This length should be enough for most hobby purposes. The strength of the field depends on just one thing: the product of the current and the number of turns. Thus, if you send 2mA current through a coil of 100 turns, the generated field is as strong as that obtained by sending 1mA current through 200 turns. The second relation says that the heat dissipated in a coil depends on only on the product of the coil's resistance and the square of the current through it.Principle 1

For a given power supply the heat dissipated goes up as resistance decreases. You might be tempted to infer this from the relationP = V2/R.But we must not forget that a real power supply is not just a fixed V. It also has an internal resistance. Usually solenoids draw quite high currents, and so the voltage drop across the internal resistance is not negligible. Let the power supply be made of a voltage source V and an internal resistance r. Then if the resistance of the solenoid is R, the current is

V/(R+r).So the heat dissipated is proportional to

R/(R+r)2.So once R exceeds r (as it will for any useful solenoid) the power dissipation goes down with increasing R. So the very first step in designing a solenoid is to have an idea about the heat that you can allow. Notice so far we have used little more than Ohm's law and the definition of power dissipation is a simple resistance. So to get an idea about the heat dissipation just hook up different resistances (of the order 50 Ohms to 200 Ohm) with your power supply, leave the circuit on for as long as you'd need the solenoid to be on, touch the resistance with you finger to judge if the generated heat feels too much or not. Choose the minimum resistance that gives you permissible amount of heat.

Principle 2

Let us assume that you have only one type of wire and a ready-made forma (we shall later tell you how to choose these). Pick just enough length of it to achieve the resistance that you worked out above. Now just the wind this length of wire around the forma as tightly as you can. Don't worry about the number of turns. This would give you the most powerful solenoid possible (within your heat requirement) with your power supply, wire type and forma. Notice one point. You might be tempted to use more than the minimum length of wire. Then the resistance would go further down (so heat dissipation would still be within limit) and yet you'd get more turns. And it might appear that a fat heavy solenoid is bound to be stronger than a lightweight one. But this is not true. In fact, the more extra turn you add the strength of the solenoid will go down!! This is because, as the number of turns increase, so does the length of the wire, and hence the current goes down. Now as you wind more turns the solenoid gets fatter and fatter. So each subsequent turn uses more wire. So doubling the length of the wire would less than double the number of turns, while the current would be halved. This would reduce the product of the current and the number of turns, which determines the strength of the solenoid.Principle 3

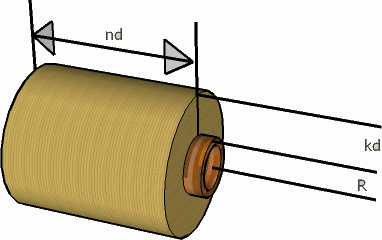

Choose the thinnest wire you can afford to use (a higher SWG number means thinner wire). Thinner wires are more expensive than thicker ones. Also, it is more difficult to work with thin wires, as they tend to snap easily during winding. But why is a thinner wire better? Let us see this by comparing a thin wire with a thick wire. The thin wire has more resistance per unit length. So to achieve the same resistance, we shall need a shorter length of the thin one. So you might think that we are going to end up with less number of turns, leading to a weaker solenoid. But you must not forget that the thinner wire keeps the solenoid less fat, and so subsequent turns take less length than for a solenoid made of thick wire. So here's a dilemma: the thick wire is longer but each turn also needs more wire; the thin wire is shorter but each turn needs less wire. Which wire is going to win the race? The answer is, as we have already stated, "The thin wire will give you more turns". We shall need some math to justify this point. Consider the diagram below.

|

| Dimensions |

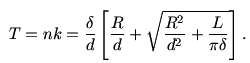

L = πn(2R+kd)k,since there are nk turns and each turn takes π(2R+kd) length of wire on an average. So we know how to find out L if we are given k. But we shall need the reverse relation: finding k for a given L. So we need to solve the above equation for k. It is a quadratic equation in k. The only positive k that satisfies this is

|

|

|