|

|

A brief Note on Mullah Nasr al-Dinby Iraj Bashiri Copyright ¨© 2004, Bashiri |

Who Is Mullah Nasr al-Din?

Mullah Nasr al-Din is a simpleton on the surface, but a shrewd, calculating, and wise man otherwise. He belongs to the Sunni world of medieval times when the performance of religious duties was a must and when people's tolerance levels were quite high. In his world, indulgence in alcoholic beverages, adultery, and fraud of all types were seriously frowned upon and, theoretically, the sultan and the beggar, alike, observed the rules of the Shari'a law. Although the rules were enforced by the ulema, the Muslims in general had a stake in making sure that they were obeyed. In his village Mullah Nasr al-Din, who lived a simple life, served as teacher, judge, and preacher. As a judge and local sage, he skillfully juxtaposes the ills of society (ignorance, class privilege, narrow-mindedness, laziness, social injustice, cowardliness, selfishness, incompetence, and the like) with lofty human values (honesty, wisdom, social justice, Islamic brotherhood, hard work, and humility). The enjoyable feature of the stories that emerge is that, no matter how incredible the situation, the Mullah usually maintains the required delicate balance between authority and laity. In his stories, neither the king nor the beggar is insulted. There are occasions when the hypocrites recognize themselves in his jokes and rise to chastise him but, with his witty remarks, the Mullah disarms them with ease and puts them in their place. Middle Easterners during whose childhood there were no comic books, newspapers, radios, or televisions, recall themselves, sitting in a sunny spot in the corner of the yard, or on the steps, or in the shade by the pool, reading about the exploits of Mullah Nasr al-Din. While reading the old stories, each generation also revised the old jokes or created new ones. Otherwise, how could the pious Mullah visit a Western-style fashion show and comment on shysters using the pretty girl models to fleece the male of the species?

Mullah Nasr al-Din's Universal Appeal

It is incredibly difficult to confine Mullah Nasr al-Din either to a particular time period or to a geographic location. In various versions, stories about the exploits of the comic character have been told and retold from Xinjiang in China to the Balkans and from Pakistan to Morocco. The very different names employed for him by various peoples, and the innovative way his deeds are tailored to various ethnic, religious, and racial requirements, testify to his universal appeal. In Turkish speaking areas, he is referred to as Nasrettin Hoja or simply Hoja. In Iranian lands, he is referred to as Mullah Nasr al-Din, and in the Arab world he is known as Joha. Each name, in turn, might have several renditions. It is not unusual, for instance, to see Khoja or Khaja for Hoja. Often Jeha or Goha are used instead of Joha. Nasr al-Din is variously rendered as Nasreddin, Nasraddin, Nasruddin and Nasriddin. And, Mullah may appear as Mollah, Mulla, Mullo, and Molla.[1]

Is Mullah Nasr al-Din A Real Person?

Alongside the legendary figure of Mullah Nasr al-Din, there has developed a real figure, at least in the eyes of the people of the village of Hortu, near Sivrihisar, in central Anatolia. According to their account, the Mullah is a historical person born in 1208 to Abdullah Effendi and Sidika Hanim. He received a traditional education at home from his father, the imam of the village. Later on, he married a girl from his village and settled. They had one son and one daughter. There is no mention of the son, but the daughter's name appears to have been Fatimah. In later years, the Mullah became a judge (qadi), traveled in Anatolia, especially to Sivrihisar, Akshehir, Karahisar, and Konya. In some reports, he even visited Arabia. He died in 1284. In early Ottoman documents there are indications of the existence of a tomb complex for him. Later on the complex is reported to have fallen into disuse. Mention of the complex is dropped from official documents until the reappearance of a tomb in more recent time. This, of course, is the tomb at Hortu. The Mullah in this story grew up during some of the most trying times in the history of the Middle East and Central Asia. People of the time had been witness to the Mongol holocaust. How else could they offset the impact of the devastation and carnage that they had experienced other than by taking refuge in humor? It is wonderful to relate Mullah Nasr al-Din to a village, a family, and a job. There are, however, no historical accounts that would corroborate the veracity of the story. In any event, historical reality is no concern of the proud people of Hortu who, each year, between the 5th and 10th of July, celebrate the anniversary of the birth of their native son. People from throughout the region participate in the celebration of the anniversary and exhibit their paintings, sculptures, and musical works. During this time, the playwrights stage their plays, while movie makers and cartoonists commemorate the Mullah's contributions to laughter and joy by screening their versions of the Mullah stories. A main feature of the celebration is a contest for identifying the individual with the most extensive repertoire of Mullah stories. In fact, less formal version of this contest takes place whenever and wherever witty fellows gather together. Like proverbs, Mullah Nasr al-Din stories keep parties together and people jolly and content.

The Uncertainty Around Mullah's Identity

Given the medieval Middle Easterners' state of knowledge and attention to events, the uncertainty around Mullah Nasr al-Din's date and place of birth is not unusual. Multiple identity claims are encountered quite frequently in the biographies of well-known figures. For instance, Mevlana Jalal al-Din, who wrote in Persian, was born in Balkh. Most of his adult life, however, was spent in Anatolia. It is, therefore, reasonable for Central Asians (Balkh was part of the Central Asian domain in early Islamic times), Iranians (he wrote in Persian), Afghans (Balkh is in present-day Afghanistan), and Turks (Mevlana is buried in Konya in present-day Turkey) to claim him as their own, and they all do. Similarly, according to the Afghans, Shahri Sabz is the resting place of the first Imam of the Shi'ites. The rest of the Muslim world, however, believes that Imam Ali is buried in the city of Najaf in present-day Iraq. Mullah Nasr al-Din seems to be another example of the multiple identity phenomena. Doubtless, a core of humorous and witty tales circulated in a place like Hortu, and, from there, merchants and Sufis took it far and wide throughout the Islamic lands. The tales were transmitted orally until the appearance of printing. Eventually, they were collected, edited and published as a volume. Additionally, Turkish scholars who have scoured the Ottoman archives in search of Mullah Nasr al-Din's identity reject the proposition that the Mullah belongs to the thirteenth century. They place him somewhere in the fourteenth or early fifteenth century. Even this conjecture is validated with the hope that eventually the archives might yield hard evidence both of the historical reality of the Mullah and an accurate life history for him.

The Mullah and Modern Reformists

Over the centuries, two groups have drawn on Mullah Nasr al-Din's interpretation of human nature for societal reform. These are the medieval Sufi merchants and the modern politicians. In this regard, it seems that the Sufi merchants have been more successful than the politicians. Using the stories, the Sufi merchants have found their way into both the hearts and minds of simple people, as well as into their pockets. The politicians, on the other hand, have used the stories as a basis for criticism of the ills of society. The problem is that the world of modern politics is too complex to be explained away by parodies using the resolutions offered by the Mullah. The politician, therefore, has to add much more of himself to create a meaningful analogy. And there is the rub. Many reform-minded intellectuals, editors, and publishers have been led to prison because their version of the joke has meant more to the authorities than what the surface of a joke suggests.

Characters and Setting of Mullah Nasr al-Din Stories

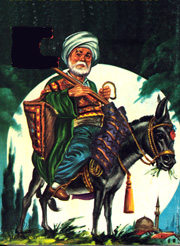

The characters in the Mullah stories are traditional individuals from all walks of life. The major player, of course, is the Mullah himself. Then there is his wife, who is sometimes referred to as Fatimah, and his little white donkey that remains unnamed. Beyond the Mullah's immediate family are his relatives, neighbors, coworkers, and the general public. Mullah Nasr al-Din's public, by necessity, is divided into amirs, qadis, commanders, kings, and caliphs, on the one hand, and women, handicapped persons, greedy people, and beggars, on the other. The setting of a Mullah story, which depends on the part of the old world a story has impacted most or to which the story is most applicable. The same story is told in Eskishehir one way, in Isfahan slightly differently, and in Bukhara and Baghdad even more so. It should be noted that although the characters, time, and space may change, in each retelling, the reader is left with the same bon mot.

Which Mullah Stories Are Genuine?

A frequently asked question with regard to the Mullah stories is whether a particular story belongs to the Mullah Nasr al-Din genre. The same question is asked about the ghazals (sonnets) of Shams al-Din Hafiz and the Ruba'iyyat (quatrains) of Umar Khayyam. The answer to this question is not simple; because, in the process, the question raises questions of its own. The answer, therefore, rests in providing satisfactory answers to the secondary questions raised. For instance, does the poem, or the story, satisfy the requirements of time and place, as well as the particular style and diction of the poet or the storyteller in question? In the case of Mullah Nasr al-Din, we should ask: Is the story concise and to the point; can the young reader grasp it with ease? Another question would be: Is the story multi-faceted? In other words, will repeated reading of the story continue to provide more fun? Most importantly, does the Mullah deliver the punchline? In short, after becoming familiar with the Mullah's time, space, and worldview, as well as with his style and characters, the reader develops his or her own sense for recognizing the grain from the chaff. We know, for instance, that the Mullah is neither a rich person nor is he bodily strong. A major question, therefore, would be whether he gets out of a predicament using his brain or braun? In the choice of the following Mullah stories an attempt is made to select stories that fit the specifications outlined above.

[1] Over the centuries, the stories attributed to Mullah Nasr al-Din have found new claimants. The 16th century Tajik humorist and satirist Mullo Mushfiqi is a case in point. Many Tajiks recognize Mullo Mushfiqi as the source of Mullah Nasr al-Din stories. This, notwithstanding the fact that the core of the Mullah stories could precede Mullo Mushfiqi by at least a couple of centuries. |

|

|

|

Mullah Nasr al-Din Stories

|

|

Table of Contents |

||

MullahíńŰs Friday Sermon

Due to his witty remarks, Mullah Nasr al-Din was always on demand, especially when he visited the larger towns. One day, in Samarqand, he was asked to deliver the Friday sermon from the pulpit. He accepted.

One Friday, when the prayer was over, he mounted the pulpit, cleared his throat and before delivering his sermon asked the audience íńķDo you know what I am going to talk about?íńý

The crowd enthusiastically shouted, íńķYes, we do.íńý

Hearing that, the Mullah got up, gathered his cloak around him, and walked down the steps of the pulpit. íńķWhat happened, Mullah?íńý The audience wanted to know.

íńķWhatíńŰs the point of preaching about something that you already know?íńý

The audience felt that they had let the Mullah down.

íńķMullah,íńý they said. íńķYou must excuse us. Give us another chance. We really want to hear your sermon.íńý

íńķFine,íńý said the Mullah. íńķI shall give the Friday sermon next week as well.íńý

Next week, after the Friday prayer, the Mullah mounted the pulpit, cleared his throat and asked, íńķDo you know what I am going to talk about?íńý

This time the crowd said, íńķNo, we doníńŰt.íńý

Again, the Mullah got up and walked down the steps of the pulpit. íńķWhat happened this time, Mullah?íńý The audience wanted to know.

íńķWhatíńŰs the use of my talking to people who doníńŰt know what I am talking about?íńý

Frustrated, the people asked the Mullah for a third chance; he agreed. Next Friday, after the prayer, the Mullah mounted the pulpit and asked the same question. This time some of the people in the audience said that they knew while some others said that they had no clue about what the Mullah was going to talk about.

Again, the Mullah got up, gathered his cloak around him and walked down the steps. This time, however, he stood on the last step and said, íńķI am happy that finally we came to an understanding. Please, those of you who know what I was going to say inform those who have no clue all that I was going to say in my sermon.íńý

Having said that, he hurried out of the mosque.

Mullah had two wives; a young wife and an older one. One day his wives came to him and said, "Mullah, which one of us is dearer to you? Mullah thought for a while, then he said, "You are both dear to me. Why?" The younger wife said, "Suppose the three of us were in a boat and the boat capsized. Which one of us would you save, Mullah? Mullah turned to his older wife and said, "Thank God, dear, that you are a good swimmer!"

|

The Cat or the Meat? |

|

One day Mullah bought a kilo of meat and brought it home to his wife to prepare for dinner that night. He then left the house. A 1itt1e whi1e later the neighbor's wife came to visit. While talking about other neighbors, the two women nibbled at the meat until they had eaten it all. In the evening, when the Mullah sat at the sofre for dinner, his wife served bread and cheese instead of meat, and said, "I am sorry, Mullah, but the cat took the meat out of the pan and ran off with it."

Mullah ate his dinner of bread and cheese quietly and went to bed.

The same thing happened several days in a row and Mullah patiently listened to the story about the cat. Finally, one night while listening to the story he saw the cat pass by. Quickly he jumped on the cat, caught it, and put it on the scales. When he saw that the cat weighed exactly one kilo, he turned to his wife and said, "Khanom, if this is the cat, where is the meat; and if this is the meat, pray tell, where is the cat?

Mullah's Quilt

One hot night, Mullah Nasr al-Din and his wife were planning to sleep on the roof. For that they had carried some of their bedding, especially a quilt that she had made to ward off the morning chill, onto the roof. While preparing to go to bed, a commotion in the alley below attracted their attention. They wondered what it was all about. The Mullah decided to go down and investigate. He threw the quilt over his shoulders and went down the ladder.

In the alley a few rogues were quarreling. One was hitting the other while some others were trying to keep them apart. Mullah entered their quarrel and tried to keep the one from hitting the other. As soon as the Mullah became really involved, one of the rogues pulled his quilt off his shoulder and took off with it. The others, too, began to run as if trying to catch the one with the quilt. Mullah, half running after them, shouted, "Hey, there. Where are you going with that? ThatíńŰs my quilt you are taking!"

The rogues did not pay any attention to him. Before long they all disappeared behind the walls of the serpentine alley.

Mullah ascended the ladder wondering what to say to his wife. His wife asked, "Mullah, what was all that commotion about?"

"Nothing dear," he quipped. "It was all about our quilt!"

Experience

One day the Mullah was walking down an alley. He encountered a large crowd standing underneath a roof, looking up. He went to one ofthem and asked, "What's going on here? Is the man up there trying to commit suicide?"

"No, Mullah," he said. "He does not want to throw himself down. He is an architect. He has built this house but he has forgotten to build any stairs for it. Now that his work is complete, he cannot get off the roof." Mullah thought for a while and said, "No problem. I can bring him down. To do that, however, I need a rope." They brought a rope and gave it to Mullah. He threw the rope onto the roof and instructed the man: "Pilgrim, tie the end of this rope tightly around your waist."

The man followed Mullah's instructions. Then Mullah, with all his might, pulled the other end of the rope bringing the man down with it. The man died. Stunned, the crowd asked, "But Mullah, you killed this man, why?" Mullah, too, was astounded. After a bit of thought, he said, "I don't know what went wrong. Several days ago a child had fallen in a well. We threw a rope down and pulled the kid up and gave him to his mother. Could it be that this method is only good for pulling up, and not so good for pulling down."

|

|

Cauldron's Child |

One day, the Mullah went to his neighbor's house and said, "Neighbor, we have several guests tonight. Can I borrow your cauldron? I will bring it back as soon I can."

The neighbor said, "Of course, Mullah;" and gave him the cauldron.

The Mullah kept the neighbor's cauldron in his house for quite some time. Then one day, he put a small cauldron inside the neighbor's cauldron and took both to the neighbor. The neighbor looked at the small cauldron and said, "Mullah, what is this small cauldron for?"

Mullah said, "Apparently, when I borrowed it, your cauldron was pregnant. At our house it gave birth to this 'child'."

The neighbor, although surprised, didn't say anything more. He took the cauldrons and thanked the Mullah.

Several days later, the Mullah went to his neighbor again and borrowed the same cauldron. This time, however, he kept the cauldron and did not return it. A long time passed. One day, the neighbor had guests. Out of necessity, he went to the Mullah's for his cauldron. He knocked at the door. Mullah opened the door. The neighbor said, "Mullah, excuse me for the intrusion but tonight we have guests. Can I have my cauldron back?"

Mullah thought for a while and asked, "What cauldron? The neighbor laughed and said, "the one that had a kid!"

"Oh, that one," said the Mullah, and added: "Neighbor, I have bad news for you. Apparently, your cauldron was pregnant this time, too, and unfortunately, it passed on in childbirth!"

One day, Mullah Nasr al-Din took his son on a journey. As soon as they left the house, he put his son on the donkey and he himself walked next to them. Passersby looking at the father and son quipped, "The healthy kid rides while his poor old father has to walk!"

Ashamed, the boy dismounted and helped his father ride for a while. Another group passing them quipped, "The poor boy has to catch up to the donkey while his old man rides like a lord."

Mullah then invited his son to ride on the donkey with him. "Look at that poor donkey," people criticized. He has to carry the weight of two healthy people."

"I think we both should walk and lead the donkey," Mullah suggested to his son. In that case, no one can criticize us. His son agreed and they began walking in front of the donkey and leading him.

"Look at those two fools," people whispered, as father and son were about to leave the village. "How can they walk in this hot weather, and go as far as they need to go, while they could ride?"

"Son,"

Mullah said to his son. "You lift up the front legs and I will lift up the

hind legs. We have to carry the donkey. No other viable option remains. Maybe

that will stop them criticizing us!"

Frightened by an unusual sound, Mullah Nasr al-Din, who was walking down a lonely road, threw himself into a ditch. There, he began to think that he had died out of fright.

As time went by, he felt cold and hungry. So he got up, walked home and brought the sad news of his death to his wife. Then he returned to the ditch.

Sobbing, his wife went to the neighbors and informed them of her husbandíńŰs death. They sympathized with her and asked, "Where is the body then?"

"ItíńŰs lying in some ditch," she replied crying.

"How do you know it is in a ditch?" They asked.

"I know," she sobbed. "Poor dear. ItíńŰs a ditch no one can see. He himself had to come home and tell me!"

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din was riding his donkey, facing towards the back. "Mullah," people asked, "Why are you sitting on your donkey backwards!"

"Who, me?" He asked. "No, I am not sitting backwards. The donkey is facing the wrong way!"

Listen to Your Mother!

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din decided that since his donkey has become old, he should buy a younger donkey. "While the old donkey can still give me rides," he thought, "the younger one can learn. Then, I can gradually phase the old donkey out and ride the younger one."

To buy a donkey, Mullah rode his donkey and to the town market. There he could see all kinds of donkeys, of all ages and colors, and all braying either for attention or for feed, or for whatever. Among the donkeys for sale a particular young one attracted his attention the most. He walked to the seller and asked," Is it all right if I look that donkey over?" The seller did not have any objections. "Yes, by all means, Mullah. Go ahead," he said.

The Mullah looked the donkey over. It was a white donkey with mild grey stripes of the type one sees on a zebra. He asked the seller for a price.

"How much, may I ask, are you asking for him?" The Mullah asked.

"This donkey, Mullah," said the seller, "is a special breed. I am asking at least one hundred dinars for him."

It was the custom in those days, especially in the Mullah's town to offer half the price asked. "How about fifty dinars?"

"You must be pulling my leg, Mullah," laughed the seller. "For you, however, I will lower the price to eighty-five."

To reciprocate, the Mullah raised his suggested price to sixty-five dinars. Eventually the seller and the Mullah agreed on seventy-five dinars for the price of the donkey. The Mullah paid the price, rode his old donkey, and holding the rope that was tied around the neck of the young donkey, he left for his village, pulling the young donkey behind him. The day was pleasantly warm and a nice fragrance wafted over the green wheat fields. The Mullah, thinking of the future and how the young donkey would make his life easier, began to dose off.

In the wheat fields two brothers, actually two rogues: lame Suleiman and clever Massoud, had been following the Mullah all the way since the edge of town. They were quite sure that the Mullah would take a nap and, by the time that he reaches the village, he would be asleep. Then, they thought, they would have a good chance to separate the Mullah from his newly purchased donkey and make some money in the process.

The rogues were not wrong. By the time that the old donkey approached the broken walls of Mullah's village, Mullah was fast asleep. He was, however, listening to the monotonous thud of the young donkey's hoofs, making sure that the rope was taught. Once sure that the Mullah will not see them, Suleiman and Massoud emerged from the wheat field and approached the Mullah's new donkey.

"Let me take the rope off the young donkey and put it around your neck," suggested Massoud.

"No," protested Suleiman pointing to his lame leg and gesturing that he can't make the same thud as the donkey.

"All right," agreed Massoud, and let Suleiman place the rope that he had taken off the neck of the young donkey around his neck. Keeping the rope taught and making the thud sound that the donkey made, Massoud walked behind Mullah's old donkey until they reached Mullah's house. As for Suleiman, he took the newly bought donkey to the market and sold it for sixty dinars.

Proud of the bargain he had struck, the Mullah called Fatimah, his wife, to come so he could show her the young donkey. "But this is not a donkey, Mullah," Fatimah exclaimed. "It's a boy!"

"A boy!" Mullah repeated as he turned around and saw Massoud.

"Who are you, boy?" Mullah demanded to know.

"I am the young donkey," said Massoud. "You bought me at the market in town."

"So I did," said the Mullah, trying to convince himself that he was not going crazy.

"I made a mistake, Mullah," volunteered Massoud. "I did not obey my mom as every good kid should," Because of that she cursed me and turned me into a donkey. But when you, a pious, upright Mullah, bought me, the curse was broken, and I turned back into the boy I was."

Mullah felt that he should not keep the poor boy away from his mother because of a mild case of disobedience. He let the boy go home. The next day the Mullah went back to the market to buy a young donkey. In the market, his eyes caught sight of a donkey very much like the one he had bought the previous day. Rather than going to the seller to haggle over the price, this time he walked to the donkey and said, "Bad boy, didn't I tell you not to disobey your mother?"

His Donkey's Helper

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din's wife , Fatimah, discovered that she needed a few items from the market. "Mullah," she said, "I am sorry, I am starting dinner and I need a few items from the bazaar. Can you ride your donkey there quickly and get those for me?

"Sure thing," said the Mullah. A short time later he rode his small white donkey to the market. There, as always, the many colorful fruits and vegetable on display in front of the shops fascinated him. Rather than staying and enjoying the scene, however, he hurried to get the items to Fatimah. He stopped at each shop, talked to his friends, and bought a few items. At the end, he found himself the owner of an extremely heavy load of watermelons, eggplants, potatoes, and vegetables.

With great difficulty, he rode his donkey backward, lest he dishonor his friends by turning his back to them. One of his friends then handed him the heavy bag. Instead of placing the bag in the saddle, Mullah held it at the end of his out stretched arm, away from the donkey. The donkey began to move in the direction of Mullah's house.

On the way, one of Mullah's students saw him supporting his tired, outstretched arm with his other arm. The student asked, "Mullah, why are you not placing the bag on the saddle?"

"Because, don't you see," Mullah whispered. "I am helping my donkey. She is carrying me and I am carrying the load!"

Preparing Halva

One day, complaining to his neighbor, Mullah Nasr al-Din said, "Neighbor, I really like halva but somehow I cannot manage to prepare some to eat."

"Preparing halva is not that difficult, Mullah," said his neighbor. "It needs some flour, some sugar, and some oil."

"Right there, you see," said Mullah. "That is in fact where the problem is." He further explained, "When there is sugar, there is no oil, and when I get oil and flour together, there is no sugar."

"Come on, Mullah,íńŰ said the neighbor. "It is not hard to bring a few items like that together."

"ThatíńŰs true neighbor," said the Mullah. "It is not hard to find all those things in one place. The problem is whether I can be found in that place!"

Borrowing MullahíńŰs Donkey

One day, Mullah Nasr al-DiníńŰs neighbor came to his door and said, "Mullah, is it possible for me to borrow your donkey? My son took our donkey to the mountains to bring some firewood. I am going to the market. It shouldníńŰt take more than an hour."

"Neighbor," said Mullah. "I would love to lend you my donkey. Except that, at the moment, my donkey, too, is outíń∂"

At this very instant, from her stall, MullahíńŰs donkey brayed as loud as ever."

Hearing that, the neighbor asked, "Mullah, I thought you said your donkey is not in?"

"Friend, " said the Mullah, "you amaze me. You mean you believe a donkeyíńŰs bray over your neighboríńŰs words!"

Once Aqa Abdul Karim, the chief rug merchant in Isfahan, invited Mullah Nasr-al Din to his house. Being the talking type, Abdul Karim spoke about almost everything under the sun including the carpet trade, the clever fingers of the girls and boys who create the most splendid products for sale in the bazaar, and above all, his own family. Although Mullah Nasr-al Din, too, had a lot to talk about, Aqa Abdul Karim did not allow him to get a word in edgewise. This frustrated the Mullah to no end.

Having described all that could be said about the carpet trade, he talked about his wife, Jamilah. He explained how wonderful she was. "In a nutshell," he said, "Jamilah holds the whole household together." Then he talked about his daughters, Akhtar and Nadereh. He explained to the Mullah how helpful they both have been to their mother. "They are," he concluded, "their mother's arms."

Here the Mullah tried to say something about his own wife, Fatimah, but Aqa Abdul Karim did not allow him the opportunity. Rather, he moved from the subject of the helpfulness of his daughters to the contributions of his sons: Jamshid and Rustam. "Even though still quite young," he said about his sons, "they have been the twin supports, propping up this family. As their teacher, of course, Mullah Nasr al-Din knew better. Aqa Abdul Karim, however, would not allow him to express his opinion one way or another.

Eventually, time for dinner placed Mullah Nasr-al Din, the guest of honor, ahead of his host. Trays full of pilaf were brought in and placed on the tablecloth. Accompanying all that, however, there was only one roasted chicken. It was placed in front of the guest of honor, the Mullah. "I have asked my wife and daughters to join us, Mullah," said Abdul Karim. You are virtually a member of the family. They even don't need to have their chadors on."

The bird was cooked in a very strange way. The beak and the claws were still attached. Abdul Karim explained, "It is the duty of the guest of honor to divide the chicken among the members of the host family according to his wishes. "The Mullah accepted the job with pleasure. He then took the head of the bird off and placed it on Abdul Karim's plate. "The head of the family," he said, "gets the head of the bird." He then gave a long spiel on the contributions of the father to the upkeep of the household. Aqa Abdul Karim was not happy at all with the Mullah's division of the bird but he could not say anything.

He then severed the neck and placed it in the middle of Abdul Karim's wife's plate, saying: "the neck goes to the member who holds the body and the head together. "Madame," he said to Jamilah Khanum, "You have earned this." The two wings he placed on the plates of the daughters. "Wings for the chicken," said the Mullah, "are like arms for the people. Those who have served as the arms for their mother deserve the wings of the bird."

At the end, he placed the legs of the bird on Jamshid and Rustam's plates and said, "As your father so eloquently said, you are your family's supports. Therefore, you receive the legs prop up the bird."

Dissatisfied with the Mullah's division, the family eyed the rest of the chicken. The Mullah went on to say, "This, leaves us with a bird with no important parts attached to it. Since I have made no contribution to the family, I will have to take care of that!"

Seeking Knowledge

Mullah Nasr al-Din, following the ProphetíńŰs saying, "Seek knowledge even if it is in China,íńŰ decided to learn to play a musical instrument. He went to a master lute player and asked, "How much would you charge to teach me how to play the lute?"

"Three dinars[1] for the first month," said the music teacher, "and three dirhams[2] the second and following months."

The Mullah assessed his money situation for the tuition and said, "Very well. But can we start with the second month?"

Mullah Goes Shopping

One day the Mullah went to the store to buy himself a pair of pants. The shopkeeper showed him a nice pair of pantaloons. "How much are you asking for these?" He asked.

"For you, Mullah," said the shopkeeper, "I will charge only five dinars."

When reaching into his pocket for money, a nice robe caught MullahíńŰs sight. He put the pantaloons to the side and asked the storekeeper to show him the robe, which he did. Mullah looked the robe over and asked, "How much for this?"

"The same price as for the pantaloons, five dinars," said the shopkeeper.

"Thank you,íńŰ said the Mullah. Then he folded the robe and put it under his arm and left the store. The storekeeper ran after him and said, "Excuse me, Mullah, but you did not pay for the robe!"

"I did, too," retorted Mullah. "I left the pants that are the same price as the robe!"

"But you did not pay for the pantaloons either," said the confused shopkeeper.

"Why should I?" said the Mullah. "I didníńŰt want them after I saw the robe. Why should I pay for something that I doníńŰt want?"

Blown Away by the Storm

One day, when he was walking home from the school where he taught, Mullah saw a vegetable patch with many vegetables ready to pick. He checked all directions making sure no one was around. Then, quietly, he entered the patch, and hurriedly picked some vegetables and put them in his bag. Unfortunately for him, the owner of the vegetable patch, appearing as if from nowhere, caught him in the act.

"Who are you and what are you doing in my vegetable patch?" He demanded to know.

"No one, really," said the Mullah. "I was blown here by the storm!"

"And why have you pulled these nice cabbages up by the root?"

"I was holding to them. They, too, must have been blown here with me."

"And the ones in the bag?" Asked the man angrily.

"To tell you the truth," Mullah said in desperation," ThatíńŰs the part of the situation that I am still figuring out!"

[1] Dinar is a gold coin.

[2] Dirham is a silver coin.

Believe In Your Own Lie

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din was walking down an alley in Bukhara. A group of children hanging around the mosque and poking fun at passersby began to pelt him with rocks. To defend himself, he thought of a ruse. Shouting at the kids, he said, íńķHave you heard the news?

íńķWhat news? íńķ the ringleader asked.

íńķThe news that the Amir is cleaning the Arg and is giving away all kinds of good things.íńý

íńķNo, we haveníńŰt,íńý said the ringleader.

íńķDoníńŰt you think you might be missing out on some good stuff?íńý

íńķI think we are,íńý said the ringleader to his friends as he headed for the Arg. The other kids followed him.

Left alone, the Mullah began to think. íńķA lot of good things are being discarded at the Arg and those good for nothing kids will get them all. I must not let them.íńý He began to run after the kids.

On His Toes

Mullah needed some water. He called his little boy, gave him a carafe and said, íńķSon, take this carafe and bring me some water. Make sure you do not drop it.íńý

Then, before the boy left to get the water, he pulled the boy to himself and boxed him quite hard on the ear. The boy cried.

A passerby who had seen the whole thing approached the Mullah. íńķWhy did you hit the boy? He didníńŰt do anything wrong,íńý he said.

íńķI slapped him,íńý said the Mullah, íńķto keep him on his toes not to drop the carafe. Of what use would it be to punish him after he breaks it?íńý

Idiosyncrasies

Mullah Nasr al-Din and his friend were talking about different peoplesíńŰ idiosyncrasies. íńķEveryone, mullahíńŰs friend was saying, íńķdoes things in a particular way. Even you, Mullah,íńý he said. íńķYou have your own idiosyncrasy. íńķ

íńķI doníńŰt believe so,íńý said the Mullah. íńķI doníńŰt have any idiosyncrasies.íńý

íńķThen,íńý asked his friend, íńķwhy do you always answer a question with a question?íńý

íńķDo I?íńý asked the Mullah.

Sweet or Salty

Mullah Nasr al-Din and his friend were at the teahouse. They ordered a large cup of tea to share. MullahíńŰs friend said, íńķMullah, let us decide who drinks first.íńý

íńķWhat does it matter who drinks first?íńý asked the Mullah.

íńķIt matters to me,íńý said his friend thoughtfully. íńķ

íńķFine,íńý said the Mullah. íńķI agree to drink first. Now tell me why.íńý

íńķI have a sugar cube with which I want to sweeten my tea, íńķ his friend explained. íńķSo now that you are drinking your half first, I can sweeten my half and drink it last.íńý

íńķWhy not drop the sugar cube in the cup and let me drink the first half?íńý Mullah suggested.

íńķNo,íńý his friend disagreed. íńķThat woníńŰt do. One cube cannot sweeten the whole glass of tea.íńý

íńķO. K. then,íńý said the Mullah, pulling the saltshaker to himself. íńķIf I cannot have my half with sugar, then I think I will have it with salt!íńý Then with a devilish look in his eyes, added. íńķAnd, I hope we are still in agreement that I will drink first!íńý

The Center of the World

A friend asked Mullah Nasr al-Din, íńķMullah, do you know where is the center of the world?íńý

The Mullah looked up at the sky then down then walked about examining the ground and finally said, íńķThere, right under the left hind leg of my donkey.íńý

íńķHow do you know that?íńý

íńķI know that for sure. But, if you doníńŰt believe me, do your own calculation!íńý

Drying Sesame Seeds

Mullah Nasr al-DiníńŰs neighbor had washed more clothes than he had rope to dry them on. He thus went to the MullahíńŰs house and said, íńķMullah, is it possible for me to borrow your old rope. I washed a few items too many. I will return it as soon as I can.íńý

íńķSorry, neighbor,íńý said the Mullah. íńķI am using it myself.íńý

íńķWhat for?íńý asked the neighbor puzzled.

íńķI am using it to dry some sesame seeds.íńý

íńķDry sesame seeds on a rope! Whoever does that?íńý Asked the neighbor.

íńķWhoever doesníńŰt want to lend it,íńý said the Mullah.

Wayward Wife

One day Mullah Nasr al-DiníńŰs friend, criticizing his lack of authority over his wife, said to him, íńķMullah, are you aware that your wife is a tramp.íńý

íńķNo,íńý said the Mullah, nonchalantly.

íńķBut she is,íńý insisted his friends. íńķShe tramps round everyoneíńŰs place.íńý

íńķNot round my place,íńý said the Mullah.

Up and Down the Minaret

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din had just walked up the serpentine steps inside a minaret in Bukhara and was resting in the shade. He was waiting for the noon hour so that he could give the call to prayer. A shabby man appeared at the bottom of the minaret and shouted, íńķMullah, I have an urgent business with you.íńý

íńķWhat is it?íńý

íńķI have to say it to your face down here,íńŰ said the shabby man.

The Mullah said o. k. and walked down the minaret.

At the foot of the minaret, the man said, íńķExcuse me, Mullah, to bring you all that way down. But can you spare a dirham. My family has not had anything to eat for days.íńý

íńķFollow me,íńý said the Mullah as he walked up the stairs. The man followed him. When they both were at the top, the Mullah turned to the shabby man and said, íńķdear friend, íńķThe answer to your question is íńÚno.íńŰíńý

Charity

Once Mullah Nasr al-Din went to his rich neighboríńŰs house to collect the zakat. He knocked. The servant came to the door.

íńķCan I help you, Mullah,íńý asked the servant politely.

íńķIs your master in?íńý Asked the Mullah.

The servant said, íńķI doníńŰt know, sir. Let me find out.íńý

The servant then left the Mullah at the door and went inside. A few minutes later he returned and said, íńķI am sorry, Mullah. My master has left for the bazaar.íńý

íńķVery well, íńķsaid the Mullah. íńķThank you. But before I leave,íńý he added, íńķI have a message for your master.íńý

íńķYes, sir,íńý said the servant. íńķI shall make sure that he get it.íńý

íńķFine, íńķ said the Mullah.íńý Please, tell your master that whenever he leaves for the market, he should take his face with him, too. It should not be left out there behind the window pane!íńý

The DayíńŰs Halva

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din asked his wife to cook him some halva. His wife agreed and made a large quantity. When it was prepared, she placed the plate of halva before her husband and said, íńķEat as much of it as you want!íńý

The Mullah followed his wifeíńŰs advice and ate most of the halva.

That night, when they were sleeping, the Mullah woke his wife and said, íńķDear, a thought just occurred to me.íńý

íńķWhat thought?íńý Asked his wife.

íńķBring me the rest of the dayíńŰs halva and I will tell you.íńý

She brought the plate of halva and handed it to the Mullah. The Mullah ate the rest of the halva.

íńķO. K.,íńý said his wife. íńķAre you going to tell me your thought? íńý

íńķBut of course,íńý said the Mullah. íńķNever to go to sleep before finishing up the dayíńŰs halva!íńý

Wife or Donkey

They asked Mullah Nasr al-Din. íńķMullah, why are you so upset about losing your donkey? When you lost your first wife, you didn't become as upset about that as you are over this loss?íńý

íńķRemember,íńý said the Mullah. íńķWhen I lost my first wife, you all helped and got me another wife.íńý

íńķFine,íńý said his friends. íńķSo what was wrong with that?íńý

íńķNothing,íńý said the Mullah. íńķNothing at all. Except, since I lost my donkey, no one has offered me another one.íńý

MullahíńŰs Moral Victory

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din, surrounded by his friends in the village teahouse, was talking about a moral victory that he had won over a mean highwayman. íńķI was coming back from town,íńý he said. íńķSuddenly, from behind a big boulder, a highway man appeared with his dagger drawn. I was frightened. I was afraid that he might either harm me or worse, take my donkey and all the good stuff that I had purchased.íńý

íńķIs this donkey yours?íńý The highwayman asked.

íńķYes, sir.íńý I said politely and pointed out that that was the only donkey I had.

íńķAre you coming from the market?íńý

íńķYes, sir.íńý I said.

íńķWere there any good buys?íńý

íńķYes, sir,íńý I said. íńķA lot.íńý

íńķGood,íńý he said. Then he asked me, íńķWhich would you hold more dear, your donkey and what you have purchased or your life?íńý

íńķMy life, of course.íńý I said.

íńķStand away from the donkey,íńý he commanded.

íńķI stood aside.íńý Then, with his dagger, the highwayman drew a circle in the dirt around me and said. íńķI am taking your donkey and the stuff or her. If you value your life, stay in this circle until I am totally out of your sight. Do not put your foot outside this circle. Do you understand?íńý

íńķYes, sir, íń∂íńýI said.

A friend, waiting for the moral victory in all that interrupted the Mullah, íńķSo, where is the moral victory in all that?

íńķThe moral victory is in the fact that I put my foot outside the circle,íńý said the Mullah with glee, íńķbefore the highwayman was totally out of my sight!íńý

The Bet

One day Mullah Nasr al-Din and his friends in the village teahouse were talking about the weather. His friends were challenging anyone who could endure the cold and stay in the village square throughout that night without heat. Mullah Nasr al-din accepted the challenge. íńķI have endured worse, íńķhe bragged. íńķBut for the fun of it,íńý he suggested. íńķThere should be a wager.íńý

íńķFine, íńķhis friends said. íńķIf you win, we will individually invite you to our houses for a sumptuous meal. If you lose, however, we expect that you to invite all of us to your house for a sumptuous dinner.íńý

Mullah Nasr al-Din accepted and walked out of the teahouse. He was sure that he could endure the cold and win all those dinners.

In the morning, his friends came to with the bad news. íńķMullah,íńý they said. íńķYou could have easily won if you had not been warmed by the heat of the candle.íńý

íńķWhat candle?íńý the Mullah asked.

íńķThe candle over there in the window.íńý

The Mullah looked in that direction. In the distance, behind a windowpane, a candle was burning.

íńķSo what does that mean?íńý He wanted to know.

íńķThat means that we all are your guests tonight.íńý

íńķThis is not fair,íńý protested the Mullah but, at the end, gave in.

That night all the friends of the Mullah, even some who were not in the teahouse the night before, were sitting in the MullahíńŰs guest room. Mullah Nasr al-Din greeted them very warmly, sat with them and, for a while, talked with them. Then he excused himself to go to the kitchen and check on dinner. He came back and reported that all was going according to schedule. íńķDinner will be served very shortly,íńŰ he announced.

Everyone was happy, especially those who did not have to invite the Mullah to their houses for dinner. Then, when he felt that his guests were hungry and uneasy, the Mullah left the room and did not return. The guests waited and waited for dinner to be served. There was no sign of either the Mullah or dinner, Eventually, they thought they should go to the kitchen and check the situation with dinner for themselves.

In the kitchen they found Mullah attending a gigantic cauldron that was being heated by a single candle.

íńķWhat is this, Mullah?íńý They protested. íńķAre you making fools of us? You caníńŰt expect a candle to heat a cauldron that big.íńý

íńķWhy not?íńý He retorted. íńķIts heat kept me quite comfortable when it reached me from the far end of the square!íńý