| Aitmatov's Jamila: An Analysis By Iraj Bashiri Copyright, Iraj Bashiri, 2003, 2004 |

| Aitmatov's Jamila: An Analysis By Iraj Bashiri Copyright, Iraj Bashiri, 2003, 2004 |

Introduction

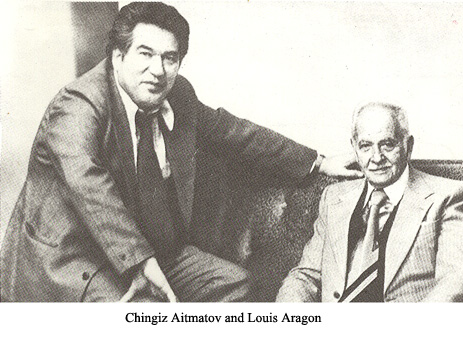

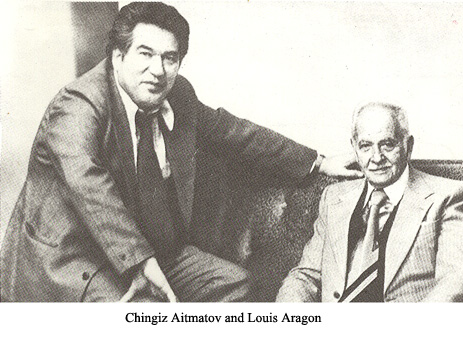

Louis Aragon's translation of Jamila into French in 1959 made Aitmatov well-known outside the Soviet Union. His translation also made Jamila available to a larger and wider audience. The English translation of Jamila, published by Progress Publishers in the same year, was not as well received. Besides being the subject of many reviews, Jamila was performed as a Kyrgyz opera in 1961; it has also been the subject of at least one motion picture.

Synopsis

Because of the war, only the aged, the disabled, and children in Seit's village are left on the collective farm. Jamila (whose husband, Sadyk, is at the front) is assigned to haul sacks of grain from the threshing-floor to the train station. Daniyar, a Kyrgyz-Kazakh youth, recently demobilized because of a leg wound, and Seit, are assigned to help her and protect her against male predation.

Daniyar is sullen and aloof. He lives on the outskirts of the village, near the threshing-floor. This is in contrast to Seit and Jamila, who are highly spirited and cheerful and who live in a multi-family compound, the Ustaka household, in the village. To amuse themselves, Seit and Jamila take to playing tricks on Daniyar. One day this goes too far. Before leaving for the station, they place a 280-pound sack of grain in Daniyar's wagon. To their astonishment, when they arrive at the station, they find Daniyar shouldering the sack to carry it over the rickety gangplank to the receiving point. In spite of Jamila's plea and the pain in his bad leg, Daniyar delivers the sack to its destination. The sack, Daniyar thinks, represents the back-breaking labor of the aged as well as the soldiers' lifeline.

This brave action gains Daniyar the respect of his new friends.

Jamila loves to sing, a trait that the Muslim women in the village held against her. Usually, when the trip along the steppes between the village and the station became monotonous, she sang popular village songs for Seit and Daniyar. Deemed incapable of singing at the time, Daniyar listened. Then, the night following the incident at the loading station, Jamila casually asks Daniyar to sing. Daniyar accepts, and before long, his voice gradually rising, the strength and beauty of his song penetrates the silence of the steppe, astonishing and delighting his companions. The contents of his songs, about the melding of the peoples, causes profound changes in both Seit and Jamila.

After that night, Jamila and Daniyar are troubled by love. Their situation becomes desperate. And since, according to village tradition, married women must not love any other man than their husbands, she asks not to be assigned to work with Daniyar.

The pure love that increasingly burns Jamila and Daniyar affects Seit as well. He no longer hates Daniyar for loving Jamila. Rather, overcome by the beauty of that love, he feels compelled to paint them in a moment of tenderness. Needless to say, his first painting lacks a true artist's touch, especially when it comes to the choice of colors. Nevertheless, Jamila keeps the painting in her suitcase as a souvenir; for the reader, this sketch expresses Seit's blossoming as an artist.

The following day, at the loading station, a fellow villager informs Jamila that Sadyk would soon leave the hospital in Saratov and return to Kurkureu. Hearing the news, Daniyar storms out of the station. Seit, too, travels home alone.

Jamila and Daniyar meet again at the threshing-floor. Jamila tells Daniyar that she has decided to leave Sadyk. Seit, who listens to the conversation from the other side of the haystack, is inspired once again. This time, however, he sees love as something tender and wonderful but, at the same time, something beyond man's control. The discretionary power of love intrigues him the most. He feels compelled to be overtaken by love as Jamila and Daniyar had been so that he can acquire the correct colors for his eventual painting of their love.

Then, one fall afternoon Daniyar and Jamila leave the village.

Initially Sadyk takes the news of the departure of his wife with a stranger in a stride. He blames Jamila while jokingly referring to the availability of women, even blonde ones. But this state does not last long. Seit's painting of the past summer comes to light, irritating Sadyk, who tears the painting into pieces and calls Seit a "traitor." Feeling the same constrictions that had made Jamila leave the village, Seit, too, leaves the depressing village to look for new and appropriate colors. As part of his endeavor to make sense of his village experience, he enters the art school and, thereafter, the academy. Finally, for his diploma painting, he paints the autumn day when Jamila and Daniyar had left the village, heading for what had appeared to Seit to be a larger and less discriminating world.

The departure of Jamila and Seit breaks up Ustaka's household unit as well.

Analysis

Sadyk mimics his father and the village folks in general. For instance, even though Seit's mother is in full control of their household, the village automatically gives all the credit for a well-run household to the incompetent Ustaka, Seit's father. Other jigits,

At the level of ideology, Jamila is more complex. Here, Aitmatov uses the arts, especially music and painting, as media for the development of his belief that the Soviet culture is compatible with the tribal adat. And that the traditions of Central Asia, such as the music of the akin, can be employed in the promotion of the new Soviet lifestyle. He further intimates that love can serve as a catalyst to unite man, woman, and nature through the arts.

There is a possibility that Daniyar, the lonely orphan boy in Jamila, might be identifiable with an akin. In that case, rather than an itinerant worker as alleged, he would be a member of an organized group commissioned to undermine Central Asian society, using its own tradition and heritage. Since this story's fulcrum potentially rests on the akin tradition, it is appropriate to delve a little deeper into this tradition.

To begin with, Daniyar shares a number of characteristics with Togtogul Satilganov, the father of Kyrgyz folklore and akin.5 Both are singers who use their good voice to attract and delight audiences. Both migrate from place to place, influencing those that come into contact with them And both rise against the oppression of the bais and advocate a common appreciation of the beauty, nature, and the freedom of the steppe.

In general, the akin were the masters of the heroic songs, ballads, and legends. Their prestige among the youth was specially high when they incorporated the people's desire for a better standard of living in songs, and when they rose against the feudal classes led by the bais and ishans (clergy). Before the 1917 revolution, the akin mingled with the progressive and democratically-minded Russians. At that time, they disseminated ideas that were detrimental to the interests of the khans and the bais. The khans responded by persecuting the akin. The akin thus became a vagabond living on the threshold of society, striving to influence as many lives as he could reach.

After the revolution, the akin retained the form of his songs but changed their contents to reflect the melding of the peoples. They also added songs that dealt with the suppression of women and with a need to overthrow the dictates of dogma. The "new" akin was then recruited and commissioned to initiate village youth into the new Soviet lifestyle.

Daniyar plays the role of a self-styled akin very well. The main objective of the akin was to inspire others to willingly undergo an absolute transformation. Different individuals responded differently to the akin's call. Some, like Jamila, used the akin as a means to break away, while others, like Seit, saw new vistas opening before them. This latter group continued on the path of transformation until they themselves became akins. In Seit's case, he became a self-styled painter with a good understanding of the colors that he used. The opening paragraph of Jamila testifies to Seit's inner enlightenment (see below). His intention to give his village of Kurkureu what Daniyar had given him, further confirms the effectiveness of Daniyar's contribution and guidance. It also resolves the enigma with which the reader is faced after reading the first paragraph. Because, if Seit is an example of Daniyar's positive influence, then life on the other side of the tracks, too, must be rewarding and fulfilling:

Once again I find myself in front of the small painting in a

Love, however, remains at the core of the story. It was through love that Jamila discovered something wonderful in Daniyar, something that had been her desire to find in a man but which Sadyk had failed to give her. In Daniyar, she found inner strength, compassion, and love. Unlike with Sadyk, from whom she only received a note of 'regards' at the end of his letters home, with Daniyar, she did not need reassurance. From his songs, his actions, and later his words, she knew that he loved her just as plainly as she loved him. He "called her every loving Kazakh and Kirghiz name," but even when not in conversation, they communicated with the language of love, a language that did not require words.

The love that grew between Jamila and Daniyar and which eventually swept them away had a tremendous impact on the impressionable Seit. He realized that the couple were at one with the beauty of the land and with the freedom of the steppe. In fact, they epitomized the land and the steppe, the very essence of the songs of the akin. Their departure meant their flight to freedom to join other Soviets in a collective effort for a bright future. It further meant that beyond the village environs, they were privileged to contribute to the building of the new Soviet life and the new Soviet citizen; they could join their brethren in the trenches, in the factories, on the collective farms, and in the hospitals.

It is in this larger love that Seit sees his own role as a possible future akin. And it is for the achievement of those special akin colors that he seeks appropriate training at the academy. He feels compelled to contribute to this larger cause, because this cause is so different from what the village families, the aksakals, and the bais had planned for digits like him. This larger love, this melody that binds all, then is the essence of Jamila. It encompasses the traditions of Togtogul Satilganov as much as it creates and sustains Jamila, Daniyar, and Seit, the new akin.

Conclusion

Aitmatov's story mimics the traditional art of the akin. The poet/musician used the old forms as vessels for expressing new ideas. This process became particularly popular with the post-revolutionary akins, who incorporated elements in their music that raised class consciousness among the workers. In Jamila, Aitmatov shows with care, love, and enthusiasm that while the apparent circumstances might seem different, the underlying facts of life remain a constant. It is up to the individual to distinguish those facets and break with tradition to employ them for his or her own benefit, as well as for the elevation of mankind.

Articles by Iraj Bashiri

Stories by Chingiz Aitmatov

See also:

Aitmatov's Life

The Art of Chingiz Aitmatov's Stories

Aitmatov's Jamila: An Analysis

Aitmatov's Farewell, Gyulsary!: A Structural Analysis

Jamila

Farewell, Gyulsary!

To Have and to Lose

Piebald Dog Running Along the Shore

Top of the page