Technical History

Historical

information about Personal watercrafts

It is far from certain just when the first personal watercraft (PWC)

appeared. For one thing, the concept is much older than its official

definition, which the US Coast Guard finally formalized as, "...a Class

A (16 feet long and less) inboard boat designed to be oper-ated by a

person sitting, standing or kneeling ON the craft rather than in the

conventional manner of sitting or standing INSIDE the craft." This

description did not exist when the Vincent Motorcycle Company, in 1955

(its final year of business), marketed the single-saddle 200cc. Amanda

Water Scooter

Or when Southern California inventor Clayton Jacobson II

built the first known standup in 1965.

Jacobson's aluminum-hulled,

rigid-handpole unit morphed into a sit-down craft in the process of his

collaboration with snowmobile manufacturer Bombardier, primarily due to

the engine. A wide, flat hull was chosen to support the weight of the

larger than prototyped 318cc Rotax, and with the air-cooled engine's

need for cooling ducts resulted in a very wide hull-fully a foot and a

half wider than the craft that were to follow. This made the 24-hp,

30-mph Sea-Doo® model 320

slow steering and rough riding, but it was the

engine's poor reliability and susceptibility to corrosion, together with

the company's decision to focus on the booming snowmobile business,

which killed off the craft after the 1970 model year. Jacobson had

continued development of

the standup however, but was not able to take his ideas to market as

long as Bombardier retained the rights. When the company pulled out of

the market, Jacobson went straight to Kawasaki. His prototype was by

this time fiberglass and sported a patented pivoting handpole and the

now-famous self-righting ability. Kawasaki and Jacobson modified one of

the company's snowmobile engines and the Kawasaki Jet Ski®, the first

commercially successful PWC and the one with the longest continuous

manufacturing history, was born. Initial Jet Ski® sales were anemic, but

by the advent of the JS440 in 1977.

Big Green was riding a wave of

increasing interest in personal watercraft generated by its own

strategic,

lifestyle-oriented marketing. A major motion picture was also to play a

role however. That same year, the highly successful James Bond movie,

The Spy Who Loved Me.

(United Artists, 1977) further entranced the

public with the personal watercraft concept when the feature film

depicted actor Roger Moore riding a water-going motorcycle; a one-off,

Tyler Nelson-patented, ski-steering craft which was later manufactured

by Spirit Marine, then a division of Arctic Cat. The first dual (front

and rear) steering PWC, the 50-hp Suzuki-powered Wetbike®

Wetbike history pictures

was

given a 60-hp 800cc engine and a much lighter body in 1986 by its later

marketer, the Ultranautics Corp., who stopped production six years

later. Wisconsin-based Surf Jet Corp. begin manufacturing in 1980 a

17-hp Subaru-powered surfboard. The company's guiding light, competitive

surfer and entrepreneur Bob Montgomery, later founded Powerski

International, maker of the current Jetboard®, a Surfjet-inspired board

powered by a Husqvarna engine. Wetjet Corp. introduced a 428cc craft by

the same name in 1985, which was sold to new owners in 1992 and is

currently produced in four 701cc models.

PWC magazines such as Splash,

Personal Watercraft Illustrated and Water Scooter (now

Watercraft World), appeared in the mid-80s to coincide with

this period of rapid industry growth. In 1987, Yamaha debuted its own

exciting Waverunner®

and 15 years later would market the world's first

major name four-stroke craft, the 9000-rpm FX140

based on its highly

successful R-1 sportbike engine. In 1988, Bombardier re-entered the

market after a 17-year hiatus by returning the Sea-Doo®

a sit-down

watercraft powered by engines built by the company's Rotax subsidiary.

In returning the Sea-Doo®, Bombardier enlisted the help of the sons of

the two engineers of the original 1968 project

In 1992 and 1993,

snowmobile giants Polaris,

and

Arctic Cat,

respectively, joined the fun. Polaris quickly established itself as a

major force and earned kudos from the California Air Resources Board for

being the first PWC to meet that state's stringent 2001 emissions

standards, while Arctic Cat's Tigershark®, a craft powered by a Suzuki

engine and actually marketed as part of the Suzuki product line in

Europe, ceased production in 2000 after making a very good showing and

even marketing a DFI model -

- the TS 1100 Li. In 1995, Southern

California-based Aquajet Corp. introduced the Jetbike®

a narrow,

dual-steering, water-planing motorcycle after the Wetbike tradition, but

with the requisite 90s styling, and at the 2001 model dealer show, Honda

unveiled an upcoming turbocharged four-stroke powered PWC based on its

1100XX bike engine.

2003 Standup are

back !

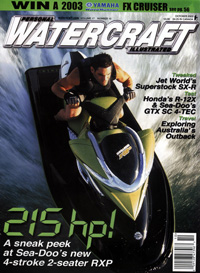

2004 RXP Seadoo, the most powerful PWC on earth

215 HP !

PWC Sales

At the beginning of the 2000 model year, there were four major players

in the PWC market: Kawasaki, Yamaha, Bombardier and Polaris. These

manufacturer's three- and four-person models are showing the strongest

growth. According to the USCG, there were approximately 1.1 million PWC

on the water during the 1998 boating season. The average retail price of

a PWC is about $10,000. Since the mid-1990s, sit-down style,

multi-passenger watercraft have made up the vast majority -- over 97% of

all PWC sales.

Research indicates that the average purchaser of a new PWC is 41

years old and has a household income of $95,400. Eighty-five percent are

male, 71% are married, 69% owned a powerboat prior to their most recent

PWC purchase, and 66% have taken or completed college-level course work.

This buyer rides a PWC most often with family and friends, and

surprisingly, the majority of PWC owners shun aggressive maneuvers while

riding and fewer than one percent report racing around buoys as a

typical activity. PWC owners spend more than $300 million on their sport

annually. In addition to the purchase of the PWC, they spend money on

boating registration fees, launch fees, trailers, fuel, insurance,

clothing, accessories, travel and watercraft-oriented vacations.

Societal Impact

The direction the personal watercraft industry has taken in recent years

has largely been due to effect the growing sport has had on local

communities. The first skirmish between municipal authorities and PWC

enthusiasts was over the sound level of PWC engines. Makers such as

Yamaha and Bombardier responded with sophisticated exhaust silencing

systems. The next issue was the effect of PWC on shorebound waterlife.

Unlike boats, PWC can be ridden in very shallow water, causing the

disturbance of plant and animal life that are part of the ecosystem of

the water body. The average PWC's top speed has climbed into the 50s and

most manufacturers have responded to the demand for more sporting

ability and the increased popularity of multi-person models by offering

an ultimate power version of their largest models which easily ex-ceeds

60 mph.

The craft's high relative speed and superior maneuverability

combined with its low water depth requirement have made it especially

irritating to the public occupying shoreland areas however. These

concerns-the raspy, droning two-stroke motor and the shallow water

disturbance-have been addressed by legislation which defines off-shore

distances PWC

are to be restricted to, and in many cases restricts PWC use to certain

times of the day, and in a few cases completely bars the older PWCs from

certain waters-the National Park Service has closed 62 U.S. park waters

to PWC, and California's Lake Tahoe permits only CARB 2006-complaint

craft. Recently, two concerns have been foremost: the PWC's exhaust

emissions, and the sport's increasing safety problems. The carbureted

two-stroke engine, until very recently the standard powerplant of the

PWC industry, together with outboard motors generates over a billion

pounds of HC emissions each year. These high emissions are attrib-utable

to the two-stroke engine's emission of as much as 30% of its fuel charge

-- part of which is oil -- into the water and air. Just 7 hrs of use of

these older carbureted marine engines reportedly releases into the

environment as much pollutants as a modern car driven 100,000 miles.

Although PWC manufacturers are, in response to increased societal

scrutiny, developing four-stroke engines, millions of examples of the

older two-stroke designs still exist. Of equal consideration at present,

because of the amazing growth of personal watercraft activity, is that

of safety. Although the boating community has long policed itself with

well-established rules of navigation and has enjoyed a good relationship

with the U.S. Coast Guard, supporting its safety requirements and

abiding by its laws, the PWC industry has only recently begun to impress

on its members the fact that PWCs are in fact boats and thus are

included in boating laws and rules. Of special concern to authorities

are the widespread use of PWC by adolescents, the disproportionate

representation among PWC users within overall marine accident fatality

statistics, the need for increased awareness of the use of personal

floatation devices (PFDs), and the dangers of alcohol use while on the

water. At present, fully 30% of marine accidents involve PWCs, though

they constitute fewer than 10% of the craft on the water. Over 200

safety bills were considered by state legislators in 1999. Out of this

came the establishment of minimum operator's ages, the requirement of

special operator's certificates (acquired by taking and passing a safe

boating course), the toughening of alcohol offenses to include DUI hits

on an operator's automobile driving license (and in some cases jail time

-- one third of all boating fatalities are alcohol related), stiffer PFD

and dead-man (lanyard) switch requirements, and new restrictions against

night-time operation.