|

|

The Northern Elen

The earliest possible European reference to Elen seems

to be Nehalennia or Nouelen a

Gallo-Belgic deity represented, like Artemis, with hunting hound (a

greyhound) and basket

of fruit (a fertility symbol, usually containing apples). She was a protector

of travellers in

early Roman times, both by land and sea. She was particularly associated with

water. She

may have been a moon goddess associated with the tides. Her known temple

locations are

Always on the coast, and surviving inscriptions often

praise her for successfully completed

voyages, or implore her for similar journeys to come.

She is invariably associated with a

large dog as a companion. She has occasionally been

associated with the Roman Goddess

Fortuna (who also accompanied Nemesis).

There was also a Germanic sea goddess called Elen, who

was probably a derivative of the

Belgic goddess. A guide to Northern mythology says this about her:

‘Elen - Anglo-Saxon

sea-goddess, particularly focussed as a protectress of seafarers and

sailors. She is clearly a source for

, or derivation of, Nehalennia, a Gaulish Goddess with

very similar attributes’.

The Gallic Celts of the Ardennes revered a forest

goddess called Arduina, associated with

a bear, she was also allegedly known as Lune. The Romans referred to her as

‘Diana of

the Woods’ (indicating parallels with Artemis). Her cult was taken up by the

pagan Franks

and continued into medieval times, one major cult centre of Arduina/Lune being

Luneville

once an important Merovingian town. The name suggests lunar connections

again, and

possibly connects with Elen (see below).

Interestingly in Bulgaria (once a centre of Artemis

worship) as mentioned above, the word

‘elen’ means ‘deer’, an animal sacred to Artemis. This is unlikely to be a

coincidence.

Our next source on Elen is Bardic literature,

particularly the Welsh Mabinogion, a medieval

text of the 11th century preserving the oral folk tales (some

allegedly originating as far back

as 500BC). These tales have become confused over many generations but remain

a good

source of Celtic lore.

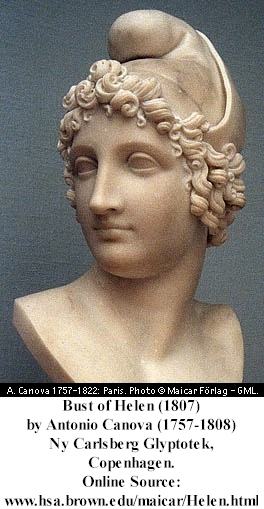

The basic lore of Elen preserved here is of a goddess of

light or beauty, some scholars derive

the name Elen from a word for ‘shining’ others from the Welsh for ‘nymph’.

One of her

popular epithets was certainly Elen the Bright.

|

Elen

Variant: Elin

|

The name presented in Welsh texts as the mother

of Constantine, so it is most likely a Welsh form of Helen

- however, it is also identical in form to Welsh elen -

"nymph". 13/4/2004 - ODFN

|

Elen was a figure, here more an elemental spirit rather

than a deity, who ruled over the

energies of nature. She was also traditionally seen as the leader of the

Ellies (‘fairies’), a

name probably derived from the Welsh

‘Ellyl’, or Elf. She was also a spirit of the trackways.

Some suggest the ‘Elves’ were pre-Celtic people and that

Elen may have been their goddess.

Another reference to Elen is as ‘Helen of the Ways’, a

mythic figure who lived in a great

castle, and desired to connect this castle to all others through a series of

paths. Later this

myth seems to have been interpreted in terms of her alleged role in the

building the Roman

road system in Britain (usually built on ancient tracks). Roman roads were in

fact named

after her in Wales, in the form Sarnau Elen, or 'Helen's Roads'. In this way

Helen would

become increasingly Romanised in Mabinogion tales.

But the Mabinogion tradition is a confused mix of

several Elens or Helens according to most

scholars. First there is the ancient Elen just

mentioned, then there are two historical women

called Helen or Elen. These three figures have become merged in the folklore

preserved in

the Mabinogion. The first mortal Elen (or Helen, her Greco-Roman name) was

the wife of

Magnus Maximus, a rebel Spanish Roman general, proclaimed Western emperor in

Britain

383 (and one of first Pendragon Kings of Britain). She was identified in

Welsh heroic

literature, genealogies and Triads as Elen Lluyddawc, 'Helen of the Hosts',

possibly meaning

armies (earliest surviving MSS. of 12th c., preserving much earlier

material). Though angelic

and Elvin connotations are also suggested in various tales. Helen’s daughter

later married

Vortigern, King of the Britons. This Elen becomes (or merges with) an

archetype who

symbolizes the power and fertility of the land. Her partner Maximus, like so

many other

archetypal Celtic heroes, defends the land, but he also brings the glory of

Rome to the Celts.

Their marriage is a ritual one between sovereign and land. Their story is

told in the romantic

tale Breudwyt Macsen, 'The Dream of Maxen Wledig (Maximus)', in the

Mabinogion.

http://www.zinescene.org/mabin/maxen.html

Here Helen also takes on the role of the queen

of the ‘dreamworld’ when first encountered. Thus associating her with other

Anglo-Celtic

dream queens, like Rhiannon and Mab. Mab is the ‘Queen of the English

Fairies’, sometimes

thought to be a descendant of the Celtic Queen of the Sidhe (the Otherworld),

Maeve. Unlike

Maeve, however, Mab is portrayed more often as a mischievous sprite rather

than a Queen,

and enjoys giving people dreams, especially erotic ones. Rhiannon was an

older Celtic goddess

whose name translates as "divine" or "Great Queen". She

is a potent symbol of fertility, yet

she is also an Otherworldly death goddess, a bringer of dreams, and a moon

deity who was

symbolized by a white horse.

The second Helen, or Helena, was the ‘Christian’

daughter of Old King Cole, the legendary

king of Colchester (ancient capital of the Belgic Trinovantes tribe). This

‘Elen’ married

Constantinus, a Roman general and became the mother (and ‘converter’) of

Constantine,

another rebel Romano-British Emperor, who later as Roman Emperor introduced

Christianity

as the official religion of the Empire (albeit a Christianity that was for

him a syncretic

crypto-paganism, much like his earlier cult Sol Invictus). Constantine was

said to have later

converted a ‘pagan temple’ into a monastery, probably in the 3rd Century

on the site of what

is now Great St Helens in London, in

honour of his mother (who had found the ‘true cross’

on one of her many ‘pilgrimages’, just as the goddess Elen always returned to

her ‘sacred

tree’ after her many ‘travels’ along the ‘ways’. A tradition still marked by

the ‘beginning of

the travelling season’ celebrated in the church of St Helen on Mayday). An

abbey of the

‘black nuns’ of St Helen was also was founded near the monastery in early

medieval times,

and their two churches built next to each other as part of one building with

separate doors

and naves. In folk tradition, Helena was mythologized as Elen the Fair, and

associated with

both the London monastery and nunnery as well as a hospital for foundlings.

Her Christian

form was as the ‘leader of heavenly virgins’, though her nuns seem not to

have lived up to

this role model, they were reprimanded by the Church in the 13th

century for ‘wearing

ostentatious veils and kissing non secular persons’, while their Abbess was

chastised for

‘keeping many small dogs in her lodgings’ (for unknown

purposes)! And in the 14th century

the notorious ‘dancing and revelry’ in the nunnery was banned ‘except at

Christmas and

only then amongst themselves’! Oddly the strange double church has the appearance more

of a castle than a church, according to some, perhaps reflecting the

Arthurian tradition of

Elen as keeper of the Holy Grail in her secret castle (see below). Again the

folklore around

this Elen has been merged with the lore of the syncretic Elen of the

Mabionigion.

A curious aside about 'St Helena' is that she was also traditionally regarded as the founder

of the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This of course not only regarded as the

'tomb of Christ', but the world's first round church and the model for Templar churches.

In reality the church was built by Emperor Constantine in honour of Helena

on the site of

a Roman temple to Venus, itself said to have been built over the cave tomb of Christ by

the hill of the Crucixion. As Romans tended to build over corresponding pagan sites,

it is far more likely that the original site was a holy hill complete with sacred tree

and a goddess cave (considered her womb of rebirth). The Aphrodite cult was of course associated with sacred prostitutes, such as the Magdalene and the Gnostic Helen.

Again

these mortal legends might preserve memories of the marriage of a Celtic king

to a woman who embodies the goddess Elen, marrying the sovereign to the land.

One

unsourced folk tradition associates Elen with St Pancras describing her as:

“A fey and shy creature, antlers on her head and dressed

in a leafy garb, her faithful dog always by her side, who was, according to

legend, sometimes seen wandering in the ancient woodland where St Pancras

station is now situated.” (Whether this connects with the Boudicca legend at

Kings Cross is not stated).

The

next source of Elen myth is in the Arthurian legends. This is far more

disguised beneath the veneer of Romance and banal Christianity of the tales,

but, given the preceding information, Elen can still be discerned in them.

Her most powerful image here is as Grail Maiden, Elen the White, an apparent

solar archetype represented as a ‘maiden of

dazzling beauty’ sitting on a golden throne in a sea girt castle (sometimes

associated with St Michael’s Mount). An interesting matrix of symbols emerges

from this association with the Grail – a vessel not only originally the

cauldron of plenty and rebirth, held once by Bran (though just as fitting for

a lifeforce bearing fertility goddess like Elen), but also Ceridwen’s

cauldron of wisdom and enlightenment, sampled by Taliesin (connecting the

Grail myth with the Gnostic Helen as Sophia). Both of these are clearly also

related to Elen’s basket of apples (with perhaps even reference to the ‘apples’

of the Tree of Knowledge, and its serpent / messenger of the goddess, being

implied). The Grail Maiden’s name was often given in a medieval form as

Elaine (or Eleanor, sometimes spelt Elonor, in Continental versions), but the

older form Elen survives in some sources. This Elaine becomes the lover of

Lancelot (who also had an affair with another Elaine, a dark seductress

sometimes called ‘Elaine the Black’, who became Galahad’s mother). There were

many other Elaines in Arthurian myth, the most famous being an Elaine who was

the lover of Perceval (himself based on British king Peredur of Galloway,

Arthur’s knights most likely being folk memories of a coalition of kings

under an overking or Pendragon); others include Elaine of Garlot (Galloway),

the wife of King Nentres (a sister of Morgan le Fey, and mother of Perceval’s

lover); Elaine of Benwick (Bourges,

100 miles to south of Paris), wife of King Ban, or Bran (and Lancelot’s

mother); and Elaine of Listinoise, daughter of King Pellinore of Northumbria,

who killed herself on the death of a lover (sometimes associated with ‘Elaine

the Black’). It seems from this that Elaine was not only an ancient

archetype, but also a name given to women of a certain royal line, often held

by both Queen and Princess at the same time. She may also have had a dual

aspect, judging from the Lancelot story. The origin of the proposed Royal

line is not known, but all the tribes indicated were non-Belgic Britons (or

Bretons), and one speculative identity is with the Parisii tribe. A tribe

first encountered by Roman historians in the ‘Paris’ region, and extending

into the surrounding French countryside (including Bourges?). After their

defeat by Rome in 52 BC many Parisii migrated across the channel and settled

in Northumberland (Listinoise). Later the Anglo-Saxon colonization of

Northumbria pushed them futher west, eventually into Ireland where they

became the Parish clan (some believe some of the inhabitants of the British

border kingdom of Rheged, and their kin in Galloway, were descended from

these migrants). If

this is true Elen would have once been the chief goddess of the widespread

Parisii clan (a connection that may invite further Trojan connections). A map

of St Helen sites certainly supports the idea that her cult entered Britain

at the Humber, the original British territory of the Parisii, and then spread

west. It is even possible that the Romans named the Parisii due to their

reverence for Elen (curiously a 13th century manuscript championing the Trojan Brutus as a worshipper of 'Diana', and a British ancestor, was produced by one Matthew Paris, a decendent of the Parisii clan). The Greek name Paris has been speculatively traced to an original

Illyrian form Voltuparis or Assparis, "Hawk", and another of

Arthur’s knights, Gawain, was perhaps significantly referred to as the ‘Hawk

of May’. The Illyrians were an ancient Indo-European tribe of central Europe

(who may have been amongst the last custodians of a very old tradition), they

closely associated with their surrounding neighbours, the early Hellenic

tribes to the south, the Scythians and Thracians to the north and east, as

well the Hallstadt ‘ancestors’ of the Celtic tribes of the northwest, all

within a Iron Age tribal melting pot of c1000BC.

In addition to the Elen’s of the classical Arthuriad, Scots Folklore has

‘Burd Ellen’ (or Lady

Ellen), the daughter of King Arthur.

While Arthur’s court itself has a mysterious female

knight called Elen Llydaw in some Welsh stories. Little information exists on this character

except that she was a knight and counsellor of Arthur.

One curious Arthurian tale adds another dimension to the

Elen story.

In 'Owain and the

Lady of the Fountain', Lunete (aka Luned and Lynette in some

versions) is taught magick by Nimue (the enchantress lover of Merlin) and

creates a

supernatural fountain in the middle of the forest. She later becomes the wife

Gawain.

The scholar Loomis suggests that LUNED or LYNETTE is a name of the moon

goddess.

Luned (-t) is the older form of the name. - (Bromwich). Another version of

the name in

some stories is Alundyne, which leads to interesting speculations concerning

the Isle of

Lundy (Merlin’s island) from some:

The resemblance of the name of the countess, Alundyne,

to the word Lundy is striking but

just to emphasise the connection an early English version of this story

reads;- "The riche

lady Alundyne, The duke’s daughter of Landuit", both names differ far

less from 'Lundy'

than do many of the names in the Arthurian myths which have become changed

over the

years. In "Jones' Welsh

Bards" the more usual name Luned is said to be the same person

as Elined one of the daughters of Brychain. The same Elined who is thought,

by some

authorities to be St. Elen, the source of the three ancient church

dedications on Lundy, at

Abbotsham and at Croyde. In short Luned is St Elined who is also called St

Elen.

Morgan le Fey was often said to be the sister of Elen

the Bright (sometimes herself called

Elen le Fey) . In Brittany the Morgans were spirits of the land and sea, the

Mari-Morgans

being specifically great sea spirits (associated with the Merfolk of

Cornwall). Their queen

was Morgan Dahut or Ahes, who caused the sinking of the ancient city of Ys

(or the land of

Lyonese in Cornwall). She seems generally to have been seen as a disruptive

influence but

was probably originally a Breton sea or moon goddess. In some legends she is

Queen of

Avalon, the Isle of Apples in the Western Ocean, where the sun sets and the

dead go, along

with her eight sisters (a making lunar nine in all). In Cornwall Morgan was

the name of one

of the illegitimate daughters of the Duke of Tintagel, her sister was Elaine.

It is possible that

Morgan was once thought of as a darker aspect of Elen.

Today Elen survives even in New Age Christian circles as

an ‘angel of light’, usually

associated with Niagara Falls! Curiously described as being formerly ‘the Goddess Elen,

an ancient Celtic solar light Goddess of holy wells, spirit within the land,

and energy matrix

light tracks’.

In complete contrast members of the Church of Satan

invoke her to adversely effect dreams!

It was Harold Bayley in his book ‘The Lost Language of

London’ who brought the archetype

of Elen back to public consciousness. His particular claim was that Elen was

the patron

goddess of London (based on the importance of Helen in London legend and the

prominence

of the Priory and Church of St Helen in its early Christian history).

Something quite possible

given that London originally belonged to the Trinovantes

tribe, who seem to have revered

Elen (if the naming of the daughter of Trinovantian King Cole is anything to

go by). He

claimed the very name of London was derived from Elen. Elen’s Don. He also

assumed

without question that the Helen of Northern Europe (Nehalennia) was derived

from the

‘Helen of the Tree’ of the Mediterranean. Describing the latter as originally

one of the most

‘primeval forces in nature’, a wilder form of Artemis or Diana, represented

as antlered and

standing by a tree with a hunting dog. An identification which leads to the

suspicion that the

Roman temple of Artemis, built where St Paul’s Cathedral now stands

(evidenced by the

Cathedral’s older surroundings being referred to as the ‘precincts of Diana’

in church

records, and the original church of St Paul itself still being the site of

deer sacrifice and

hunting ritual in medieval times, a ‘voodoun’ aspect of some sections of the

early Christian

Church), was actually originally built on the site of a

shrine to Elen in her antlered form.

Later though it seems the Romans recognised Elen in her own right and equated

her with

the oriental Helen (perhaps leading to the belief that the Britons was

descended from the

Trojan Brutus, just as Rome had been founded by the Trojan Romulus, thus

creating a

common ancestry for Romano-Britons), a tradition that carried over into

Christian times

(and was compounded by the mistranslation of London’s old name, Trinovantium,

as Troa

Nova, or New Troy).

Referring to Nouhalennia, a goddess he finds all over

Europe, and in many parts of Britain

(including Lands End and the Scilly Isles, both said to be part of Lyonese,

the Celtic Atlantis),

Bayley claims the Nou part of the deities name is a

prefix meaning ‘new’, which identifies a

specific ‘New Moon aspect’ of a goddess called Halen or Alen (as the princess

or daughter).

This subtle distinction he relates to the two churches of Helen in London, Great

St Helens

and Little St Helens. He also points to the festival of

the Allan apple as a survival of her cult

(‘allan’ meaning

cheerful). As well as observing that the Welsh term ’alain’ meant fair

or

bright, while the Irish term ‘allen’ refers to great

beauty. Bayley plays with names a lot to

find Elen almost everywhere, but some are quite convincing, for instance the

similar Celtic

names for certain rivers, Elan, Ilen, Alan, Alaune, Len,

Lyn, Lone and Lune. He also points

out that ‘Ellen’ was an old name for the Elder tree (for the Celts a tree symbolising change,

rebirth and associated with the Cauldron) and ‘Hollin’ for Holly,

before revealing

that the Irish word ‘Aileen’ meant green plain, and may have been related to

Llan, meaning

sacred enclosure (curiously the words ‘ley’ and ‘line’ have similar

derivations). Much of this

may be sheer coincidence, but the different derivations claimed for ‘Elen’

are not unusual

given the taste for punning demonstrated in many pagan Mystery cults.

While both Helens are associated with Artemis and have

many similar features direct

descent seems unlikely. As we have seen the Northern Elen is mostly

associated with

flowing water and the moon, while the Oriental Helen is associated with fire

and the sun.

The etymology of their names also appears to be different (and there is

certainly no

connection with Middle Eastern etymologies). Both are referred to as

‘shining’ however

and associated with light (or life force). It is thus probable that both

goddesses are derived

from a much more ancient European deity, a goddess of energy, or light, associated

with the

Sky (and equally with the sun and moon and stars), as well as with the more

immanent

energies of the Earth, much like the Egyptian Hathor and her partner Horus

were. In fact

just as Hathor later became to be associated with both the classical

Aphrodite on one hand

and Sekhmet on the other, so did Helen become associated with Venus and

Nemesis.

Suggesting they both reflect a more ancient and less specialised deity, which

represented

more than just the parts of the

universe, as later pagan deities tended to (the details of which are

still under researched, there are apparent connections with Egypt in the Illyrian myth, but how

is still a mystery). The local Helens were probably dim memories of this ancient goddess,

specialised according to

regional culture.

Curiously however Europe’s most central ley line the ‘St Michael’ line

passes out of

Palestine through Rhodes, the oldest home of the oriental Helen, on through

Greece and Italy,

straight through Bourges, a home of the Arthurian

Elaine, on through both St Michael’s

Mounts (Brittany & Cornwall) and across Cornwall,

with its own St Helen tradition, before

ending in Ireland.

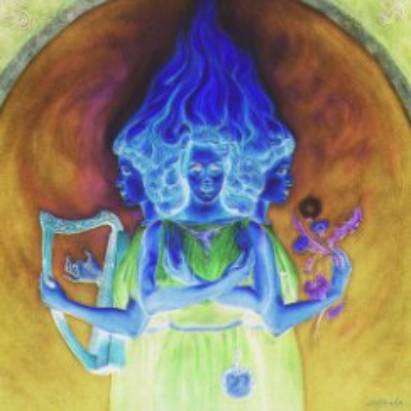

In modern ‘Theosophical’ metaphor we might say Helen

represented power, energy and

light, particularly the ‘Astral Light’, both as lifeforce and astral

energies, as well as the leys

and waters which transmitted them, along with their

tides, and the celestial bodies originating

them. More specifically she was also a symbol of the serpentine path of the

more subtle

‘Earth energy’, as it weaved its way across the landscape vitalising the

environment. Her

solar and lunar aspects also seem to have been recognised by Bayley and his followers

when they refer to her as a ‘goddess of balance’.

Bayley inspired many Elen devotees some of whom even see Nell Gwynn, the

mistress of

Charles II as the last royal ‘bride’ to represent Elen! As the following

extract relates:

‘Nell Gwynne

(1650-87) the mistress of Charles II was supposed to have lived at the

spacious country house situated at Bagnigge, St Pancras. It is possible that

she did, in the

17th century,

the area consisted mainly of fields, and churches. Also, the St

Pancras/Battle

Bridge area had always been Royalist in tendency. However, the importance of

Nell Gwynne is that her life

and her character accrued symbolic

details that made her a living representation of Elen, or

Helen, the 'genius loci’ or patron

deity of London. Nell, a diminutive of Eleanor (or Elonor),

comes from the same root as Elen,

Helen, and the Celtic Goddess, Noualen, who is depicted

in art much as Nell Gwynne is; a

beautiful young woman, holding a basket of fruit with a small

dog beside her.

The complex question of the symbolism of Helen cannot be discussed here

but basically she is an important

deity, both Solar and Venusian in nature. She is often

associated with wells, and also with

'leys' (Sarn Elen). She is usually called by an epithet

bright or shining, or beautiful; it

is interesting that Nell Gwynne's surname means 'white' in

Celtic languages.’

Elen has become

a stock character in neo Pagan mythology and psychic questing, often

absorbing other goddesses, such as

the Irish Bridget and those ancient moon goddesses

grouped by Christians under the name

St Mary, as the interesting neo Pagan analysis in the

link below demonstrates (much ‘New Age’ thought is hampered by poor psychic

practise,

‘magical thinking’, and a desire to link the entire world’s mythology into

one whole –

demonstrated in its sometimes bizarre

etymology. The following example is not free of

this trend but is far better than

most).

http://www.bridgetcheri.com/bridget.htme

Appendix – The Goddess Brigit and St Bride

The Britonic Celtic goddess of fire, light and life,

called Brigid in Ireland, Bride (Breed)

in Scotland, Brigantia in Britain and Brigandu in Gaul,

was of very similar nature to Elen,

and probably evolved from the same precursor. Her

original name, Brigit, is believed to have

been derived from Breo-saighit or ‘Bright Arrow’, probably referring

to lightning (which

represented a spontaneous manifestation of the life force, creating magickal

crystal balls

when it struck sandy beaches, or causing fires in woodland). In Ireland,

where her cult was

most developed, she represented the source of the life giving and psychic

energies of the

world, which seem to have to been divided into five types:

i) The physical

energies of the world, in particular fire;

ii) The life

energies of nature, which produced fertility and fecundity;

iii) The energies of all life forms, producing health and vitality;

iv) The psychic energies of humans, producing ideas,

visions, and art;

v) The creative energies of the gods

(also shared by at least some humans, such as

Blacksmiths and Magicians, in

Celtic tradition), which created new order from chaos.

All of which were regarded as just different modes of

the same universal energy,

metaphorically envisioned as fire and light, or alternatively as wind or

flowing water. Bride

had five aspects that embodied these energies; the Fire goddess; the

Fertility goddess, who

like many other goddesses represented the life force underlying the fertility

of the land and

the fecundity of animals; the Healer, who dealt with biological energies; the

Seer (or muse),

the giver of visions and inspiration to humans, and the Craft goddess,

dealing with creative

powers and those who wield them, such as Craftsmen (Blacksmiths in

particular). In Ireland

her role as mythic representative of the fertility of the land was shared

with many other

tribal goddesses, leading her specialisations to be emphasised in her definition,

which

eventually gave her a three fold aspect (with her fertility aspects merged

into her Healer

archetype and her fiery aspects given practical

manifestation in her forge and hearth). In

other places her more primitive form remained, particularly as Brigantia (who

also retained

her more destructive aspects). In Ireland she had a dedicated body of

priestesses who

tended her perpetual flame on her altar in Kildare, and assisted her work on

Earth. Her

original cult was obviously closely related to Celtic Shamanism and its

survival in Witchcraft. In the 5th century

her high priestess, also called Brigit, or Bridget to be precise, was

allegedly converted to

Christianity by St Patrick, and her priestesses converted to nuns. However

even if this was

true the ‘nuns’ and their leader St Bridget, seem to have carried on much as

before. And

St Bridget, or St Bride as she became known elsewhere, evolved into a new

Christian

archetype within the Celtic Church indistinguishable from the goddess she

replaced. The

Irish pagans claimed that Brigid invented many useful things including

whistling and "keening",

the mournful gong of bereavement, not surprisingly the Irish Christians would

make the same

claim for St Bride.

In one of her most popular forms the goddess Brigit was

the particular representive as the

spontaneous and eruptive emergence of energy, life or inspiration. This was

the sudden flash

of lightning (or inspiration) from above, or the eruptive spring (or feeling)

from below. It was

also the natural phenomena of birth and emergence, both of animals (and

humans) and of

vegetation with the coming of Spring. In Scotland she was regarded as a

serpent queen who

on Feb 1st arose from the burial mounds (connected to the Underworld)

signalling the end of

Winter, the start of the lambing season and the first signs of Spring. The

keeper of the gates

to the underworld, the reservoir of lifeforce as well as the abode of the

dead. Modern pagans

equating this with the rise of Kundalini energy and sexual energy. This

‘bringing life into the

world’ also included the creation of human artefacts for the ancients, who

often regarded

such ‘things’ as having their own life and character. Swords for instance

were given names

and seen as being born in the fiery energy of the Blacksmith’s forge, a

special instance of the

magickal creative energy represented by Brigit. The serpent was her sacred

animal, as was

the swan, the goose and the lamb (the latter also being a totemic animal for

the Knights

Templar). She was also often represented as a ‘virgin’ herself newly born

into the world, so

could be regarded as the Irish form of the new moon aspect of Elen,

Nouhalennia (according

to Bayley). And like her has associations with both the power of water as

well as a more

fiery energy.

This finally brings us back to Elen and London. A

similar goddess to Brigit, quite possibly

Nouhalennia, was probably associated with the sacred spring emerging near

what is now

Fleet St (which crosses the ancient river Fleet, now

covered over as a sewer). This spring,

and its goddess shrine, had been in use as a sacred site

since at least 1000 BC, according to

archaeologists. The ‘holy well’ and temple which replaced it may have been a

Roman or

Romano-British development a thousand years later, but the last Celtic people

to settle near

it are said to be the Irish raiders, who colonized the

banks of the Fleet in the 6th century, at

the time of the collapse of Roman Britain. These people would have without

doubt associated

the site with Brigit. A medieval legend claims that the first church was

built here soon after

by St Bride visiting from Kildare. Whether this was the same St Bride

converted by St

Patrick, an abbess with the same name, or pure myth is uncertain (legend

assumes the

former though). The descendents of these Irish immigrants later rebuilt the

church and

worked on the reconstruction of much of London in early medieval times and

beyond. The

church was thus naturally dedicated to St Bride, and retained this special

dedication till the

building of the 8th and current church on the site by Sir

Christopher Wren in the 17th century.

Later St Brides would become the favoured church of poets and inspired

writers, and later

still became known as the ‘Journalist’s Cathedral’ for the Fleet Street

newspaper community.

In her role as the ‘marrying maiden’ (perhaps in part

due to confusion over her name!)

St Bride also became the patroness of marriage, and the spire of her church

in Fleet St

became the inspiration of the modern wedding cake design (after it had been

damaged by

a lightning strike!).

Appendix B – Other Celtic Goddesses and Elen

|