Bismarck

The Construction

Operation Rheinubung

The Bismarck's departure

To the Denmark StraitThe Iceland Battle

The Bismarck escapes

THE CONSTRUCTION

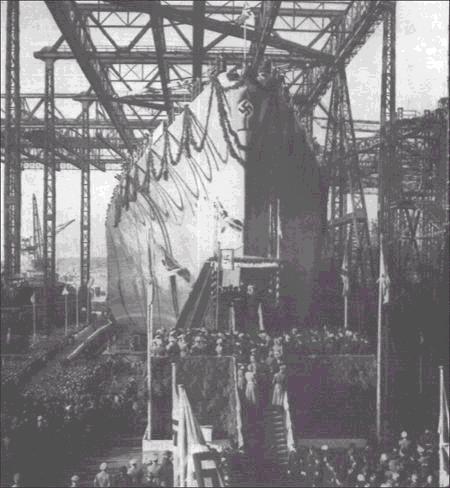

The battleship Bismarck was ordered to be built by the shipbuilding firm Blohm & Voss founded by Hermann Blohm and Ernst Voss in 1877. The keel was laid down on 1 July 1936 at the Blohm & Voss shipyard facilities in Hamburg, yard No. BV 509, on slipway 9. By September 1938, the hull was already complete to the level of the upper deck. The launching ceremony took place on Tuesday, 14 February 1939, and was attended by thousands of people, military personalities, government officials, and yard workers. Adolf Hitler delivered the pre-launch speech and the hull was then christened by Frau Dorothea von Loewenfeld, granddaughter of the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, after whom the ship was named. Moments afterwards, at 1330 Bismarck's hull slipped into the water for the fist time.

After the launching, the ship was moored to the equipping pier where the boilers, turrets and all other parts of the superstructure began to be installed. In addition, the original straight stem was replaced with a new "Atlantic" bow that offered better sea-keeping capabilities and a new arrangement for the anchors. The war started in September 1939, but despite this and the hard winter that came after the construction work continued as scheduled.

In April 1940, the first members of the future crew began to assemble aboard, and with them the 47 year-old newly-appointed ship's commander, Captain Ernst Lindemann. The Bismarck was still completing and these men started the first phase of training intended to get in touch with the battleship's equipment recognizing boilers, turbines, turrets etc. On 23 June, the Bismarck entered the floating dry dock No. V-VI where the three propellers and the MES (Mangnetischer Eigenschutz) magnetic system were installed. The keel was also painted over. The Bismarck got out of the dry dock on 14 July and then she was again moored to the pier. The crew, officially formed by 103 officers and 1,962 non-commissioned officers and men, was still not complete, and new men came aboard gradually.

On 24 August 1940, the ship was finally ready to be commissioned and enter in active service with the Kriegsmarine. It was a cloudy day, and the crew was formed on the upper deck waiting for Captain Lindemann to appear in order to begin with the commissioning ceremony. Soon after, Lindemann approached the battleship on a white motor boat which carried the German battle flag. The Captain stepped on board and procceded to inspect the honour guard first, the officers, and the rest of the crew thereafter. The First Officer, Commander Hans Oels and Lieutenant von Müllenheim-Rechberg escorted him. After inspecting the crew, Lindemann went to the afterdeck to pronounce some words. Behind him there were two signal mates at the flagstaff, one of them, master signal mate Franz J. Scharhag carried the battle flag rolled up under his right arm. After the address, Lindemann gave the order to hoist the battle flag and the German national anthem began playing. The battleship Bismarck was now in service and all the men were dismissed and ordered below decks.

OPERATION RHEINÜBUNG

After the success achieved by the surface ships in the Atlantic waters during the winter of 1940-1941, the German Naval High Command decided to launch a much more ambitious operation. The idea was to send to the Atlantic a powerful battle group formed by the battleships Bismarck, Tirpitz, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. These last two battleships were in Brest, in the occupied France, since 22 March, after a successful campaign of two months in the North Atlantic under the command of the Fleet Chief, Admiral Günther Lütjens, in which they sank or captured 22 ships with a total tonnage of 116,000 tons. The Bismarck which had almost finished her training would soon be ready for her first war mission. But the Tirpitz which had just been commissioned on 25 February still had to spend some months of training, and it was not probable that she would be ready for the spring. Moreover, the Scharnhorst had to enter the dry dock and do some repairs in her machinery so this would immobilize the ship at least until June.

On 2 April, the High Command made clear the strategy to follow in its operation order. Without the Tirpitz and the Scharnhorst, the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen would be sent to the North Atlantic at the end of April under the command of the Fleet Chief. These two ships would be joined later by the Gneisenau sailing from Brest. The task of the German ships was to attack the convoys operating in the North Atlantic over the Equatorial line. Nevertheless, after the experience got with the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau in the last months, now the enemy convoys were strongly protected by British cruisers or battleships. So if that was the case, the powerful Bismarck would take care of the escorting ship thus allowing the other ships to attack the convoy without any problem.

The British Admiralty was worried and suspected that the Germans were planning a big operation with surface ships. The British knowing about the presence of the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau in Brest and the danger that would represent their sortie to the sea, made arrangements to immobilize them through aerial bombings. On 6 April, a Coastal Command plane of the 22º Squadron scored a torpedo hit on Gneisenau's stern. The British plane was shot down, but the Gneisenau had to enter the dry dock for repairs. A few days later, during the night of 10/11 April, the battleship was hit by four bombs during a bombing by the RAF, so this would lengthen her repair work during months. Only the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen would be ready to sail and attack the convoys.

So it seems that there were more than enough reasons to cancel the Bismarck's departure and wait until the autumn for the Tirpitz or the battleships stationed in Brest to be ready. Also the short spring nights increased the possibility to detect the German ships before they could get to the Atlantic. Nevertheless, the idea to send the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen to the Atlantic in the spring of 1941 was not bad at all. The United Kingdom was in a critical situation, and give her five months of "relative tranquility" in the sea would only strengthen her position. We also have to take in consideration that it was possible that this could be the last opportunity for the German ships to reach the Atlantic, since the war with the United States would have to come some day and then it would be much more difficult. It was also ironic maintain a ship with the potential of the Bismarck in her home base doing nothing. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder wanted to maintain the pressure on the British and decided to go on with the operation. The most important thing was that the two German ships could reach the Atlantic unnoticed. Then they could get lost in the immensity of the ocean and attack the convoys.

Meanwhile, on 8 April, Admiral Lütjens had met the U-boat Chief, Vice Admiral Karl Dönitz in Paris. Both Admirals knew each other well as they had coincided in several occasions before the war. At the conference they outlined the support that was to be given to the Bismarck by the U-boats. The U-boats would carry on as usual in their normal positions, but if any opportunity arose for a combined action with U-boats they should exploit it to the full. A U-boat officer was therefore assigned to the Bismarck.

On 22 April, Admiral Lütjens established the details of the operation now code named Rheinübung (Rhine Exercise). The departure of the German ships was imminent, but on 23 April, a magnetic mine exploded near the Prinz Eugen while on her way to Kiel, and because of the repair work the operation was delayed for some days. On 26 April Lütjens and Raeder met in Berlin and could talk about the situation. On 5 May, Hitler visited Gotenhafen to inspect the Bismarck and the Tirpitz. Raeder was absent, and Lütjens received the Führer, but he didn't inform him about the next sortie of his ships. The departure of the Bismarck was again delayed on 14 May, this time because her port crane had to be repaired and therefore a couple of days more were lost. Finally on 16 May, Lütjens informed the High Command that the ships were ready, and the date for the beginning of Operation Rheinübung was established for 18 May.

THE BISMARCK'S DEPARTURE

At 1000, in the morning of 18 May 1941, Admiral Lütjens inspected Prinz Eugen's crew, and after that a conference was held on board the Bismarck, where the Admiral exposed the operative plan to the ships' commanders, Captains Ernst Lindemann and Helmuth Brinkmann. It was decided that if the weather was favourable, they would not stop in the Korsfjord (today Krossfjord), and instead they would sail north to refuel from the Weissenburg before getting into the Denmark Straits between Iceland and Greenland.

At noon, the Bismarck left the berth and anchored in the bay to take supplies and more fuel. Operation Rheinübung had just begun. At about 2130, the Prinz Eugen weighed anchor, and at 0200 in the early morning of 19 May, the Bismarck left Gotenhafen. Both ships sailed separately until they joined together off Rügen Island at noon on 19 May. Then Captain Lindemann informed the crew by the loudspeakers that they were going to the North Atlantic to attack British shipping for a period of several months. After this, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen sailed west escorted by the destroyers Z23 (Commander Friedrich Böhme) and Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt (Commander Alfred Schemmel). At 2230, the destroyer Z10 Hans Lody (Commander Werner Pfeiffer) with the Chief of the 6th Flotilla (Commander Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs) on board, joined the formation. During the night of 19/20 May the German ships passed through the Great Belt which remained close to merchant ships, and reached the Kattegat in the morning of 20 May.

On 20 May, once in the Kattegat, the German battle group was sighted by numerous merchant ships. At 1300, the German ships were sighted in the Kattegat by the Swedish cruiser Gotland (Captain Agren) which reported the sighting to Stockholm. Soon after, from the British embassy, the Naval Attaché, Captain Henry W. Denham transmitted a message to the Admiralty in London. The German fleet had just been discovered. In the Afternoon, the 5th Minesweeping Flotilla (Lieutenant Commander Rudolf Lell) joined the battle group temporarily to help the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen pass through the German minefields that blocked the entrance to the Kattegat.

At dusk on 20 May, the German ships were already getting out of the Skagerrak near Kristiansand. It was then when they were sighted from the coast by Viggo Axelseen, of the Norwegian resistance, who informed the British in London. During the night the Germans sailed north, and in the morning of 21 May they entered the Korsfjord south of Bergen with clear weather. As we already know, Admiral Lütjens wanted to continue to the north without stopping in Norway, but because of the clear weather he decided to enter the Korsfjord and continue the voyage at night protected by the darkness. The Bismarck anchored in the Grimstadfjord and the Prinz Eugen with the three destroyers in the Kalvanes Bay.

At 1315, a British Coastal Command Spitfire sighted and photographed the German ships in the Korsfjord. During their stay in the Korsfjord, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen painted over their striped camouflage paint with grey. The Prinz Eugen also refuelled from tanker Wollin. The Bismarck did not refuel and this would prove to be a mistake later. Around 2000, before the night fall, the five German ships left the Norwegian fjord, and after they had separated from the coastline set a course of 0º at 2340, due north.

This is the famous photograph taken by the Coastal Command Spitfire at 1315 on 21 May. The Bismarck can be seen to the left anchored in the Grimstadfjord with three merchant ships. The Spitfire (Lieutenant Michael Suckling) had taken off at 1100 from Scotland.

Meanwhile, on the British side they were alarmed after the discovery of the German ships in Norway, so the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral sir John Cronyn Tovey ordered the heavy cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk, both under the command of Rear Admiral William Frederick Wake-Walker, to patrol the Denmark Strait. Shortly before midnight on 21 May, the battle cruiser Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales together with the destroyers Achates, Antelope, Anthony, Echo, Electra, and Icarus left Scapa Flow under the command of Vice Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland.

TO THE DENMARK STRAIT

On 22 May, the weather got worst, and the Germans who had intercepted a British message knew that they had been discovered and that the enemy was looking for them. During the night, the German battlegroup headed north, with the three destroyers on the lead and the Prinz Eugen closing the formation. At 0420, the destroyers were detached and headed east to Trondheim, while the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen kept their northward course at 24 knots. At 1237 there was a submarine alarm, and the German ships began to zig zag for about half an hour. When the alarm ended, the very top of the turrets and the swastikas on the deck were painted over, and afterwards the group set a northwest course, to the Denmark Strait. During the whole day the sky was covered with clouds, and the fog was so thick that the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen, were forced to switch on their searchlights from time to time in order to maintain the contact and keep their positions. The weather conditions seemed now very favourable for the German ships to pass through the Denmark Strait and reach the Atlantic unnoticed.

Meanwhile, Admiral Tovey after receiving news that the German ships had abandoned Norway, left Scapa Flow at 2200, with the battleship King George V, the aircraft carrier Victorious, the light cruisers Kenya, Galatea, Aurora, Neptune, Hermione, and the destroyers Active, Inglefield, Intrepid, Lance, Punjabi and Winsor. The battle cruiser Repulse sailing from the Clyde was to join them later the next morning.

On 23 May the weather remained the same. At 1811 in the afternoon, the Germans sighted ships to starboard, but they were actually icebergs. Meanwhile, they had reached the ice limit, and set a course of 240º. At 1922, the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were sighted by the British heavy cruiser Suffolk at a distance of seven miles. The Suffolk sent an enemy report: "One battleship, one cruiser in sight at 20º. Distance seven miles, course 240º." The Germans also noticed the presence of the British cruiser, but they could not engage the enemy because the Suffolk remained hidden in the mist. About an hour later, at 2030, the Germans sighted the British heavy cruiser Norfolk, and this time the Bismarck opened fire immediately. She fired five salvos, three of them straddled the Royal Navy ship throwing some splinters on board. The Norfolk was not hit by any direct impact, but had to launch a smoke screen, turn around and hide in the mist like the Suffolk had done before. After this the British cruisers took up positions astern of the German ships, the Suffolk on the starboard quarter and the Norfolk on the port quarter, just trying to keep the radar contact and waiting until more powerful units could engage the Germans.

On board the Bismarck the forward radar set had been disabled by the blast of the forward turrets, and Admiral Lütjens ordered to change positions. The Prinz Eugen with her three radar sets intact took the lead, and the Bismarck with her more powerful artillery situated astern of the heavy cruiser just in case the British cruisers came any closer. This change would produce great confusion on the British the next morning. At about 2200, the Bismarck turned around trying to catch the Suffolk, but the British ship run away maintaining the distance.

THE ICELAND BATTLE

The Iceland Battle, also known as the Battle of the Denmark Straits was a naval combat of little more than a quarter of an hour. A clash of titans in which the largest warships on Earth (Bismarck and Hood) were put to the test with the result of the sinking of one of them.

In the early morning of 24 May, the weather got better and the visibility increased. The German battle group maintained a course of 220º and a speed of 28 knots, when at 0515, the Prinz Eugen's hydrophones detected the noise of two ships from port side. At 0537 the Germans sighted what they thought it was a light cruiser at about 19 miles (38,480 yards - 35,190 meters) on port side. At 0543, another unidentified unit was sighted to port, and thereafter the alarm was given aboard the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. Aboard the Bismarck the identification of the enemy ships was uncertain, and they were now mistaken by heavy cruisers. The British warships (the battle cruiser Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales as we are going to see next) sailed against the German battle group following a course of 280º at 28 knots. Vice Admiral Holland, aboard the Hood, familiar with the vulnerability of his battle cruiser in a long range combat, was probably trying to get closer quickly before opening fire. Admiral Lütjens did not have any other choice but to accept the combat.

Due to the similar silhouettes of the German ships, at 0549 Holland ordered to engage the leading German ship (the Prinz Eugen) believing she was the Bismarck, and afterwards the British ships made a 20º turn to starboard on a new course of 300º. At 0552, just before opening fire Holland identified the Bismarck at last and ordered to shift target to the right-hand ship, but for some reason Hood kept track on the leading ship. Aboard the Prince of Wales however, they correctly targeted the Bismarck which was coming behind the Prinz Eugen. Suddenly, at 0552, and from a distance of about 12.5 miles (25,330 yards - 23,150 meters), the Hood opened fire, followed by the Prince of Wales half a minute later at 0553. Both ships opened fire with their forward turrets, since their after turrets could not be orientated towards the target due to the unfavourable angle of approach. The first salvo from Prince of Wales landed right astern of Bismarck, and afterwards the "A" turret's no. 1 gun broke down temporarily and could not fire anymore. Second, third and fourth salvoes fell over. Hood's first two salvoes fell short from Prinz Eugen throwing some splinters on board.

The British shells were already landing close, but the German guns still remained silent. Aboard the Bismarck, the First Artillery Officer, Lieutenant Commander Adalbert Schneider, in the foretop command post, requested several times permission to open fire without getting any answer from the bridge. Finally at 0555, while Holland was turning 20º to port with his ships (a manoeuvre that now let the Germans correctly identify the Hood and a battleship of the King George V Class), the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen retaliated concentrating their fire on the Hood.1 Bismarck's first salvo landed short. At 0556, Prince of Wales' fifth salvo fell over again, but the sixth straddled the Bismarck even though aboard the British battleship no hits were observed. The initial fire of the Germans had been excellent, and at 0557, the Prinz Eugen had already obtained a hit on Hood, around the mainmast in the boat deck causing a big fire which spread as far as the second funnel. The Bismarck had also been hit, and Lütjens ordered the Prinz Eugen to change target to this battleship, together with the secondary battery of the Bismarck which had just entered in action.

At 0600, the Hood and the Prince of Wales turned another 20º to port in order to bring their after turrets into action, but at 0601, from a distance of less than 9 miles (18,236 yards - 16,668 meters) the fifth salvo from Bismarck hit the Hood, penetrated her armoured belt and reached an after magazine where it exploded. The German observers were impressed by the enormous explosion. The Hood, the mighty Hood, pride of the Royal Navy and during 20 years the largest warship in the world, cracked in two and sank in three minutes at about 63º 22' north, 32º 17' west. The after portion sank first stern up and centre down, followed by the forward portion, bow up centre down. There was not even time to abandon the ship. Vice Admiral Holland and his fleet staff, the commander of the Hood Captain Ralph Kerr, all of them perished. Out of a crew of 1,417 men, only three survived and were rescued three and a half hours later by the destroyer Electra (Commander Cecil Wakeford May) and landed in Reykjavik.

After the Hood blew up, the Bismarck turned to starboard and concentrated her fire on the Prince of Wales which was now in clear disadvantage. The British battleship had had to alter her course to avoid the wreck of the Hood, and this placed her close to the Germans. At 0602, the Bismarck hit the Prince of Wales in the bridge, killing everybody there, except the commander, Captain John Catterall Leach and another man. The distance had decreased to 14,000 meters, and at 0603, the Prince of Wales launched a smoke screen and retreated from the combat after being hit three more times by the Bismarck and three more by the Prinz Eugen. The Prince of Wales fired three more salvoes with "Y" turret while retreating, but firing under local control did not obtain any hits. At 0609 the Bismarck fired her last salvo and the battle ended. For the British, this must have been incredible, the Germans kept the same course instead of following the damaged Prince of Wales and finish her off.

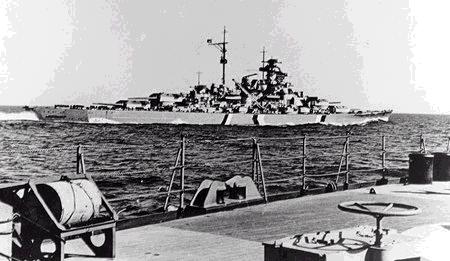

The Bismarck firing against the Prinz of Wales. The photo on the right is the most well known of the battleship Bismarck and one the most famous of World War II as well. It was taken from the Prinz Eugen between 0602 and 0609. At this time the Hood has already been sunk and the Bismarck hit on her bows. The after turrets "Dora" and "Caesar" are firing against the Prince of Wales in one the of last salvoes of the battle. Do not be confused, it's not at night, the blast of the guns has darkened the photo.

The Prinz Eugen was not hit during the battle and remained undamaged, even though some Hood's shells landed close to the German heavy cruiser in the opening phase of the engagement. However, the Bismarck had been hit by three shells probably from the Prince of Wales. The first shell hit Bismarck amidships below the waterline in section XIV, passed through the outer hull just below the main belt, and exploded against the torpedo bulkhead. The second shell hit the bows in section XXI, over but close to the waterline. The projectile entered the port side, passed through the ship without exploding, and left an exit hole of 1.5 meters in diameter. Around 2.000 tons of water got into the forecastle. The third shell simply passed through a boat without any consequences.

As a result of the hits received, the top speed of the Bismarck was reduced to 28 knots, and the ship was down by the bow. The damage was not especially serious, the Bismarck maintained intact her fighting capability, good speed, and there were not any casualties among the crew. However the loss of fuel was to condition the following course of operations.

the hull of the Bismarck at the day of the launching

Bismarck and Prinz Eugen on exercise in the Baltic