One day I will die, like everyone else. After my family holds a memorial service on land, my body will be taken aboard ship and carried at least 3 nautical miles from land, to water at least 600 feet deep, maybe more. I read somewhere that the ocean is a wilderness experience as soon as you get out of your depth. That might not be true anymore at popular dive destinations, but it certainly is still true at the distances and depths where burials are conducted. There, my casket, or burial shroud as the case may be, will be tipped overboard, and my body will begin a final journey into the wilderness.

If I still had ears to hear, I would hear a din. The ocean is far from silent. It is a noisy place. Maybe I would hear the tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap-tap of a "carpenter fish," that is, the sailor's term for the sound of a sperm whale. Maybe the rat-a-tat-tat of a black drum fish, or the low clicks of croaker fish. More likely, the most common noise in the ocean, the snap-crackle-pop of thousands of shrimps on the move. I remember once, halfway between Hawaii and San Diego, in the middle of the night, over the underwater listening device came a chilling, ghostly wail. It did not repeat, and we had no idea what it was. Such is the mystery of the undersea wilderness.

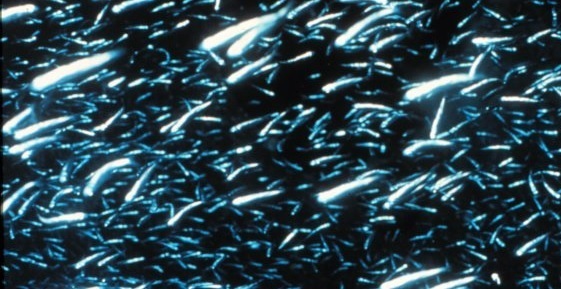

As my body descends, it crosses the deep scattering layer: teeming masses of small fishes, so numerous that the air in their swim bladders creates an echo return -- a false bottom that can fool the unwary sonar operator into thinking the ocean is shallower than it really is. Eventually, I reach crush depth. Those metal caskets the Navy uses -- surely they are not built like those deep-sea submersibles that explored the Mariana Trench, or even like a regular submarine. Submarines have their crush depth; surely my casket does, too. The pressure forces out any remaining air in my lungs, and any built-up fermentation gases that would otherwise have floated my body back to the surface.

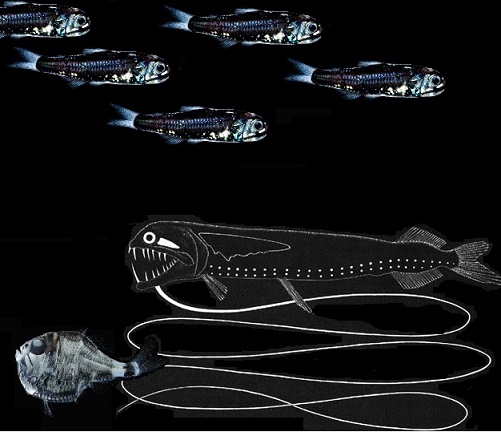

By this time, I will be in the depth where it is always nighttime -- where no sunlight has ever penetrated. Lantern fish, flashlight fish, deep-sea anglerfish, dragonfish, all the miniature monsters of the abyss will shine their lamps on me. If I still had eyes to see, I would surely find it a beautiful light show. No sunlight has ever reached here, but the deep is not without light. Here is that "ocean depth of happy rest" that Henry van Dyke evoked in his Hymn to Joy.

Eventually, my body will hit bottom. Maybe on the slopes of a seamount; maybe crash among the rugged crags of the Mid-Ocean Rift; or maybe settle gently into the mud and ooze of an abyssal plain. In time, hagfish will find their way in and pick my bones clean. And if perchance the hagfish miss anything, crabs with neither pigment nor eyes will pick over what is left. In time, my molecules of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium will be free floating in the water. The ocean is not stagnant; bottom water flows, albeit slowly, and eventually, my molecules of nutrient will reach an upwelling zone.

Eventually, my body will hit bottom. Maybe on the slopes of a seamount; maybe crash among the rugged crags of the Mid-Ocean Rift; or maybe settle gently into the mud and ooze of an abyssal plain. In time, hagfish will find their way in and pick my bones clean. And if perchance the hagfish miss anything, crabs with neither pigment nor eyes will pick over what is left. In time, my molecules of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium will be free floating in the water. The ocean is not stagnant; bottom water flows, albeit slowly, and eventually, my molecules of nutrient will reach an upwelling zone.

I will have become one with the ocean.