Joachim Meyer Fechtbuch of 1600

Translation Project

Topics and Tips

John Lennox 4/4/00

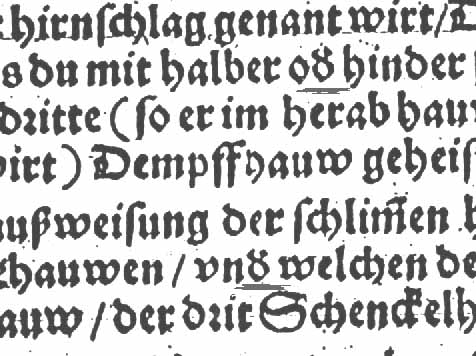

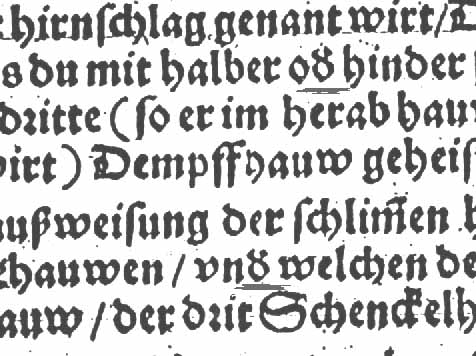

What is the letter underlined in the picture below?

Andrew Brew 3/24/00

Using an over-score to indicate an abbreviation was common in pre-Norman England, both in English and Latin, so I guess the tilde to be a version of the same convention.

Manfred Klein 3/23/00

The combination of "n~", "m~" or "e~" does not exist in modern or medieval German. The Heiliges römisches Reich (Holy Roman Empire), which included today's Germany and also parts of Italy, Belgium, France and Switzerland, was split into many Fürstentümer, or principalities, who cared little about the Kaiser (Emperor, from the Latin "Caesar"). The last powerful Kaiser was Friedrich II. von Hohenstaufen, who died in 1250. In the time after Friedrich, the principalities gained power and influence, each with its own dialect of German, and everybody writing as they heard and spoke. So the n~ is just like "ng" or "nd".

I've also seen "zeriffen" in your text, which should be "zerissen". Don't mistake small "s" and small "f". They look nearly identical, but the "f" has a line crossing the main stem.

Ernesto Maldonado 3/22/00

As I recall from Elizabethan printing, the tildes are an abbreviation for an "n" or "m". What I have seen was a straight line with marks at both ends (sometimes stylized as a modern tilde) used for an "n". For an "m", they would put a mark through it to signify the middle line. This was a holdover from monastic days when such abbreviations cut down on the time to hand-copy a book.

Mark Rector 3/22/00

Many of you have commented on the recurrence of the tilde ( ~ ) over certain letters, usually "n", "m" and final "e". IMO, it is a typesetter's shorthand for an omitted letter, i.e., "kom~en" = "kommen", "un~" = "und", and "seine~" = "seinen". (see examples on p.321 online at the web site)

We should make an effort to include the tilde ( ~ ) in our transcriptions.

John Lennox 3/16/00

The note about the "K" and the "R" being identical is correct. You need to know the words to know which one it is. This is also the case with the lower case "u" and "v", especially when it comes at the beginning of a word: "unn", not "vnn". A rule of thumb that seems to work well is that if the next letter after the symbol is a consonant, it's probably a "u". If it is a vowel, it's probably a "v". Also, as in old English, old German doesn't necessarily spell the words the same way modern German does: i.e., "Grundt" is "Grund" (ground). I have also found that old German doesn't necessarily capitalize every noun as modern German does.

Mark Rector 3/16/00

The word is "Kopff", or head (that's where ya hit 'em!), not "Ropff".

The capital "Z" looks like an ornate numeral "3".

"Zorn" means "angry" or "wrathful" as in the "cut of wrath" or the "guard of wrath" or the "thrust of wrath" ("zornhauwe, zornhüt and zornort, respectively).

Ernesto Maldonado 3/13/00

I have an idea that may be useful for others. I was planning on making each line on Microsoft Word transcription text last as long as one line of original text. No more, no less. I think that this would make it easier to figure out what my question marks refer to.

I was at the HACA seminar in Houston last Saturday. I noticed that they had copies of the Chronicl alter Kampftuenfte, which are hand-to-hand combat manuals from 1443-1674. I picked up the last copy, but thought you might want to know how to order it from Germany. The ISBN is 3-87892-031-8 and it is published by Verlag Weinmann in Berlin.

Manfred Klein 3/4/00

"Gnaediger" means dear, merciful, gracious and was used when speaking to nobility.

Home

joachimmeyer@angelfire.com

joachimmeyer@angelfire.com

Click to subscribe to joachimmeyer

Click to subscribe to joachimmeyer

Click to subscribe to joachimmeyer

Click to subscribe to joachimmeyer