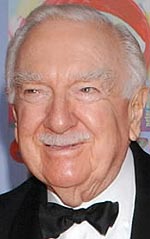

Walter Cronkite |

Good jumping Jehoshaphat!

The Post is 100 years old? And I was there when it was less than half that age - 53 years ago?

It isn't possible, one is inclined to mumble. But it is. And that year of 1932, it seems like yesterday.

The Post plant was out of town - way out of town, way out on Polk by the railroad tracks. It was a streetcar ride downtown - downtown was the metropolis that stretched all the way from the bayou, south to Dallas, and from San Jacinto on the east to Milam on the west. It was so busy down there that, if you had a car, sometimes you had to circle the block a couple of times before you could find a place to park.

Some shops were beginning to stretch out along Main and Travis and Fannin, way south almost to Hermann Park, but mostly what you found that far from downtown were just groceries and drug stores and filling stations and cleaning shops. If you were driving out Westheimer west to the ranch country, you'd better check your tank before you got to the last gas station at Shepherd Drive.

Compared to the city it is today, Houston was a small town then, and, compared to the size 40 and gray thatch of today, I was a small boy and I guess The Houston Post was a small newspaper although to me it was the New York World, the Washington Star and the Chicago Tribune rolled into one. (Two of those three are dead now - RIP.)

Gov. Hobby owned the paper then, as he did for so long thereafter. I don't ever remember seeing him, but I did once see Mrs. Hobby. I thought she was the most beautiful lady I'd ever seen - and I still do.

I wasn't really employed there; tolerated is more like it. I had discovered journalism to be my life's ambition in my junior year at San Jacinto High so that summer found this awed fresh-faced and freshly scrubbed kid at the city editor's desk begging for a job.

I stood down at the more seriously scarred end of that scarred desk - the end that Editor Ed Barnes rested his feet on while, leaning back in his chair, he examined his tongue with the hand mirror he kept for the purpose in his top drawer. I never knew what he was looking for, but I trust if it was something evil, he never found it.

I had every reason to like him. After all, he gave me my first newspaper job. The terms were simple and definitely pre-union - I'd put in whatever hours schoolwork and more gainful employment permitted, and in return I'd be given lunch money and carfare.

The service club luncheons saw a lot of me that year - that way it didn't come out of Ed Barnes' budget. Every week I heard the bell ring at Rotary and the Lions roar and whatever it is the Kiwanians do, and every once in a while their speaker would make enough news to warrant a paragraph or two in The Post. Then I would know the ego-fulfilling truth that only a published writer can experience: I could watch fellow passengers reading MY story on the Mandell line streetcar taking me home (1838 Marshall Ave., where, a half-block away, just the other side of Hazard, our part of town ended and the mesquite began its long march westward.)

That Post city room probably would appear laughably small to the people who occupy the Post editorial rooms today. I don't seem to remember more than 10 or 11 desks in the whole room and they were crowded into the inadequate second-floor space allotted them. But it had a wonderful aura, the model of every newspaper movie you ever saw.

The floor was littered with the wadded remains of a few dozen rejected leads. The surgeon general hadn't yet delivered his stern warning and the air hung heavy with smoke. The din was frightful as deadline approached and typewriters clacked and, in the adjoining room, linotypes clinked.

And telephone bells clanged. They seemed louder then. They were in a separate Bell-system black box screwed on the side of the desk, and the instruments were the old stand-up type. It was the rare reporter who didn't answer the phone by holding the mouthpiece stand in his right hand and giving it a deft flip so the earpiece went flying out of the cradle and into his outstretched left hand. I went home and practiced after that first night at The Post and I had the maneuver mastered by morning.

But it was the end of the first week before I learned a more important telephone lesson. I submitted my first expense account: three roundtrips downtown - 30 cents; three telephone calls - 15 cents.

"Hey, kid." The summons was from the City Desk. "What's the 15 cents for phone calls?"

Another call across the room:

"Hey, Harry, show the kid how to make a phone call.

"Kid, Harry'll show you how to make a phone call."

"You always carry two pins, see," Harry explained, turning back his coat lapel and removing two straight pins. "Then you put one pin in this wire and the other pin in this wire, pinch the pins together and you get your phone call for nothing."

I next submitted an expense account for phone calls only when the telephone company got wise and replaced those two wires with an impenetrable cable.

The Post wasn't particularly noted for its munificence then (what newspaper ever has been?) and apparently there had been a series of executive changes just before I got there. At any rate they told the story of the day that someone strung a banner across the city room: "Be kind to the office boy, he may be managing editor tomorrow."

Actually I made more money when I carried The Post than when I reported for it. That lasted a couple of years until my supervisor caught me rolling the papers and throwing them from my bicycle instead of folding them and placing them quietly on the front porches. The Post was thoughtful of its readers even 53 years ago.

Those readers were an eclectic group, even then. The ship channel had been completed and the East Texas oil finds had come not so many years before, and the boom was beginning. Of those customers of mine between West Alabama and Westheimer, Woodhead and Hazard, I doubt there was a single Houston native. They came from the north and the Midwest mostly, several from St. Louis in the move of the Gulf Oil headquarters.

Gulf had just built the city's second skyscraper - all 34 floors of it. It had succeeded the Neils Esperson Building by a few feet as the city's tallest. There was talk that Mrs. Esperson, thwarted from adding floors by her building's crowning glory, its pillared dome, was going to jack up the whole building and put the additional couple of floors under it. I think that was one of the stories I reported to The Post only to have more experienced reporters knock it down.

There were a lot of rumors to be had around the Esperson Building lobby. The bank of pay telephones at the rear of the lobby was "home office" for the oil speculators. When they hit they moved upstairs or, later, to the Gulf Building, and when they lost it again they moved back to the Esperson lobby. There was a drug store, Madden's, I think, at the corner and over coffee at its counter many of the early fortunes were made in Houston.

As New Yorkers today on a rainy day can make their way underground through interlocking subways around mid-town, on those terribly hot summer days you could almost make your way around downtown Houston under the canopies that most buildings still had over the sidewalk in the best pre-air conditioning Southern style.

And the oases to which the speculators - oil and cotton, for cotton still had a few minutes left to be king - repaired at day's end was the lobby of the Milby or the Rice Hotel to sit under the electric fans, or to the Majestic Theater, which was the first to advertise "Air Cooled Comfort."

The Shamrock Hotel at what was called "the End of Main" was still a dream of Glenn McCarthy's and most people thought it was a nutty idea.

"Nobody will ever go that far out to a hotel," they said, but his friends in the oil business did and it became nationally famous although the folks who had built fine homes in a suburban development called "Braeswood" were mighty annoyed that their quiet neighborhood should be sullied by a commercial building in its vicinity. After all, they had moved out south to get away from that sort of thing.

River Oaks was the principal "fancy" area, but it was a little too far out for a lot of folks, and many newcomers wished they could afford one of the fine homes on the lovely palm-bedecked esplanade that was one of Houston's most beautiful streets, Montrose Boulevard.

There was something left of the gracefulness of the old Southwest when The Post and I were a half-century younger, but the boom was on, and, as someone once said about something else, the rest is history.

Reprinted with permission. Thanks to former Post book editor Liz Bennett for digging up this gem.