Tamborito in Pese

The caja, pujado and repicador [Native drums made of hollowed trunks which are sealed with cowhide. The “caja” is short and squat. The “pujador” and “repicador” are long and very narrow. They differ in gender: The male pujador is deep and sonorous while the female repicador chatters and laughs up and down the scale], having been dried thoroughly in the sun, begin to sound forth, and no sooner have they commenced than old and young start to drift in. Each drumbeat is an ivitation which the girls translate perfectly. For one and all arrive in the shortest possible time.

At the strains of the first real melody the room can no longer contain the many spectators. There is the caja, with its rhytmic puco-puco; the pujador, held fast between the knees of a strapping young rascal, vibrates beneath the blows of his huge fists; and the repicador that leaps, that roars, that whistles, that quavers, that all but speaks, which, under the ministrations of Perdi’s agile hands brings tears to the eyes. And all three of them, played together, diffuse into the atmosphere a symphonic poem.

And how graciously sound the silver voices of the girls as they clap hands to the beat of their song. Their bodies sway in tune with the music and beginning with the “cantaora alante (the soloist) who stands beside the caja, the circle of girls which ends close to the repicador grows slowly smaller. Breaths come short and fast, spirits soar and yield to an atmosphere bathed in romance, in sensuousness, in love.

The tamborito is contagious. Its intoxicating rhythm and underlying emotions are communicated to all. Its cadences are mixed with the turbulence of jealousy; with the palpitations of pleasure; with the resonance of kisses; with the laughter of deception; with the honey of coquetry; or the pain of sorrow.

The ‘cantaora alante,’ intones the plaintive melody:

The Technique of the Tamborito

No Panamanian can resist the witchery of our national dance so filled with passion and so typifying gallantry and the gestures of love-making, love-making with leaps and dips, with cries and exclamations, with advancing and retreating. And since the spirit of all Panamanian youths and maidens is filled with coquetry at the sound of the Tonada (Refrain of the song chanted to the beat of the drum) and the beat of the drums, the national dance becomes a means of matchmaking.

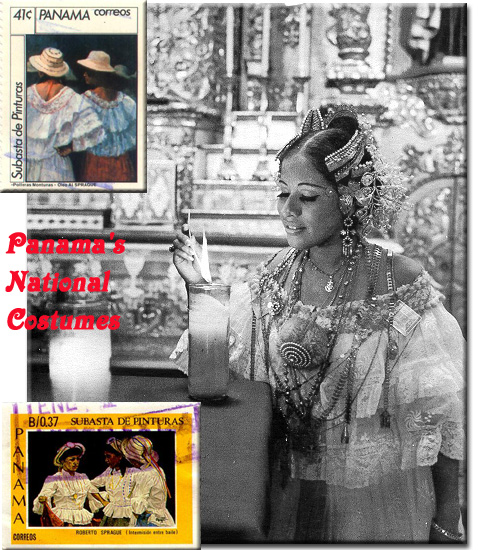

The women generally attend the Tambor empolleradas, that is, wearing the national dress, that costume which is voluptuous in spite of its ruffles. The Peruvian poet, Jose Santos Chocano, says that “the pollera of the Panamanian woman is much more tempting than the nudity of Venus.”

The women gather at the side of the drummers in a semicircle which, as the number increases, takes the form of a horseshoe facing the drums. A Caja, which is a large drum beaten with two sticks or thick balls which carry the rhythm of the Tonadas, and is next to the Cantadora Adelante who always stands first in the semi-circle; a Repicador, a drum of high-pitched sound, which carries the rhythm of the dancers and indicates the steps; and one or two smaller deep-toned drums, known as Pujas, which make a duet with the principal drum or Repicador.

The Cantador Adelante starts the song. The rest of the women sing the estribillo, carrying the beat with their handclappings.

The Tonadas are widely varied. Generally they consist of two verses paired for no particular reason and chosen at random by the Cantadora, interpolated by an estribillo sung by the chorus of women, but sometimes the verses are much more than two.

The refrain of the chorus is unchanging, but each Tonada has its special one. The songs themselves seldom lack a theme. Politics supplies it at times, the supporters of a cause taking advantage of the gayety of the Tambor to make party propaganda. National events are also recorded in these expressions of joy.

For example: In 1830 - in order to extol a feat of arms of General Tomas Herrera, Panamanian father of American independence, this was sung:

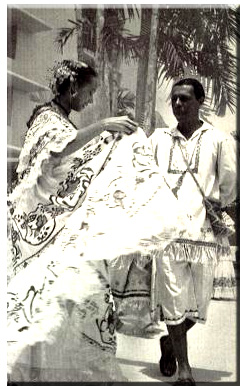

When the singers and the drummers once are in tune a man steps out of the surrounding group, approaches the chorus and invites a partner. He usually begins with the Cantador Adelante, by means of a nod of the head, a bow, or by putting his hat on her head, and then directs himself with dancing steps to the center of the circle, followed by the lady. From here they both approach the drums in order to give Los Tres Golpes, or rather, three broken steps backwards, immediately followed by a whirl. The woman barely suggests the three steps but the man bends his knees deeply as an act of submission to his lady. After the whirl, which is done simultanelously, they perform El Escobilleo, in which the woman, with whatever charm God may have given her, spreads wide her pollera skirt on one side and gathers it up high on the other, so that the rich laces and the white cloth of the linen petticoat can be seen, and thus, with light movements of the arms and all the grace at her command, she takes a series of tiny steps from one side of the circle to the other, her face wreathed in smiles and eyes filled with tropical brilliance, so that the man who follows her, also doing the Escobilleo, leaps, kneels, shouts and turns in circles, sometimes going off at a distance, then again approaching his partner with his arms extended, with which he surrounds her neck or her waist without touching her, or fanning her with his hat if he has not already placed it on her head when asking her to dance, or with one of the numerous hats which his friends are accustomed to throw at the feet of the dancing pair as homage to their skill, and which he seizes.

When the singers and the drummers once are in tune a man steps out of the surrounding group, approaches the chorus and invites a partner. He usually begins with the Cantador Adelante, by means of a nod of the head, a bow, or by putting his hat on her head, and then directs himself with dancing steps to the center of the circle, followed by the lady. From here they both approach the drums in order to give Los Tres Golpes, or rather, three broken steps backwards, immediately followed by a whirl. The woman barely suggests the three steps but the man bends his knees deeply as an act of submission to his lady. After the whirl, which is done simultanelously, they perform El Escobilleo, in which the woman, with whatever charm God may have given her, spreads wide her pollera skirt on one side and gathers it up high on the other, so that the rich laces and the white cloth of the linen petticoat can be seen, and thus, with light movements of the arms and all the grace at her command, she takes a series of tiny steps from one side of the circle to the other, her face wreathed in smiles and eyes filled with tropical brilliance, so that the man who follows her, also doing the Escobilleo, leaps, kneels, shouts and turns in circles, sometimes going off at a distance, then again approaching his partner with his arms extended, with which he surrounds her neck or her waist without touching her, or fanning her with his hat if he has not already placed it on her head when asking her to dance, or with one of the numerous hats which his friends are accustomed to throw at the feet of the dancing pair as homage to their skill, and which he seizes.