|

|

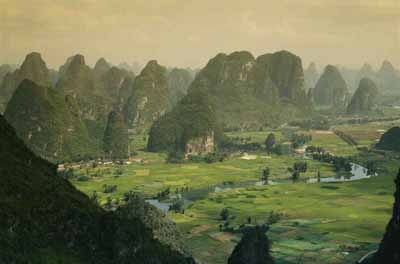

Hunanese countryside from the window of a train, the awesome spectacle of Central China's heartland.

|

I met Judy at the door of the student dining hall, after a late-night bowl of chillied wonton soup at the malatang table, Hamish, Bonnie and I squatting on low stools exchanging jokes with the students. Judy was a short, serious, dark-eyed girl - she spoke Chinese with clear vowels in a low alto tone; in the dim lamp-lit night air she seemed graceful and intelligent. Judy was a friend of Bonnie's - a dorm mate before Bonnie had begun to live with Hamish - and as Bonnie was such an exceptional girl, I rather admit that I evaluated Judy in the light of Hamish's fiancee. As we walked together to the university's marble bridge, conversation was not limited to the simple and obvious questions and answers that Chinese students regularly and repeatedly pose to their foreign teachers; Judy proved to be an interesting conversation partner, and, standing over the lake laughing with Hamish, I had the feeling that I was a little too much the fool, and that Judy was fascinating enough to make me rather ill at ease. At home, I expressed an interest in seeing Judy again, and conequently was the subject of humour for the rest of the evening. Bonnie rather rashly called Judy to let her know she'd made an impression - Judy laughed it off with the comment, 'foreigners... they always think Chinese girls are easy'. I slept in a hurt and sour mood. It was to be the only occasion upon which Judy would impress me at all, for it eventuated that Judy was in fact arrogant, prejudiced, and rather stupid. Bonnie, as it happened, was in the habit of avoiding Judy for the mostpart, owing to her opinionated and awful nature. Once, when collecting a duvet from Bonnie's dormitory with her, we encountered Judy again, who managed to offend me two or three times in conversation - upon hearing that, in my opinion, Chinese and Western people, all being human, had the same drives and basic desires, Judy accused me of lying - she said that because I was a foreigner, I certainly looked down on Chinese people. When I protested that this wasn't the case, she harrumphed and glared out of the window. Despite this, Judy's one gesture of friendship occurred when a three day break was due early in April, and she invited the three of us to travel with her to her nearby hometown of Zhangjiajie. A nationwide (and perhaps worldwide) attraction of no small fame, Zhangjiajie is an immense park where unusual geological conditions have produced a unique topography of columns of rock as high as mountains. Despite a tense relationship with Judy, we agreed to travel with her. Face Foreigners in China often note a preoccupation with 'giving face' in the national culture. Face-giving has deep roots in China, in many situations it is the preferred medium to show respect or love. Far from simple public gestures of deferment and politeness, face-giving seems complicated and strictly coded: many Chinese now consider it a weakness, as oftentimes expedient and efficient methods and occasions are stalled due to excessive giving of face. With Judy, giving face was mandatory, and it was clear that our trip to Zhangjiajie would be milked for every particle of face possible. Judy had arranged accomodation in a friend's hotel right at the expensive gate area at the park entrance, and it was clear that her intentions were to enjoy as much glory as possible for organising our trip. Grateful for the opportunity to see an extraordinary place, we were loathe to complain, however right from the outset it seemed clear that Judy would be a difficult and overbearing travel companion. On the morning, Hamish and I were slow to prepare - Bonnie was conscious of the time and our increasing lateness, although it was clear to us that we had more than enough time to prepare at a leisurely pace, and we were reluctant to follow Judy's military schedule. Judy, when we met her, was furious, and blamed Bonnie (for not organising the foreigners more efficiently) and was so otherwise unpleasant that I immediately regretted agreeing to travel. I put on headphones and ignored her, preferring instead Si Qin Ge Ri Le. Judy didn't speak to me anyway - conversation with me was so clearly irrelevant in the gathering of her fortune in face. Towards Zhangjiajie We entered the railway station rather unusually through a tunnel under the tracks and then a hole in the back fence. Not a common way to get onto the platform, I asked why and was told we would be purchasing a 'special' ticket on board the train. Rather predictably, this turned out to be the bribing of a corrupt conductor for half-price tickets. I'm grateful that my Chinese was not advanced enough to understand Judy's remarks to the conductor concerning her foreign companions. "Give us two girls a cheap ticket", she said, "but charge those two lao wai full price, they can afford it". Judy, as it turned out, despite being an advanced student of English, had a very dim view of foreign people - in her eyes, Hamish and I were arrogantly exploiting China, had arrived here to mock the locals and export as much money as possible overseas like the opium merchants of old. Our meagre salaries and eagerness to learn Chinese counted for nothing when taking into consideration our cold, alien hearts. I sat at another table to avoid her ignorance. There was certainly much to see outside the train. Every inch of Hunan is farmland, every mountain has been chiselled into bands of rice paddies. The train would climb high over broad, lime-green valleys of rivers and straight rows of vegetables. Small clusters of farm houses at the bases of bare cliffs, distant fat grey cows with bicycle-handles for horns, mile upon mile of perfect Hunanese cropland, China's legendary rice-bowl. Not even Judy could ruin it. She did, however, spoil our arrival somewhat, with her discovery that security in her hometown had been tightened thanks to the concurrent visit of China's second-in-command, Zhu Rongji, who was visiting the park on his way to Jishou University for an historic inspection that we would be missing. Judy's 'special tickets' would not be accepted, and as we had to present the tickets before leaving the station, we were hopelessly stuck on the platform whilst Judy, face falling away with each passing moment, struggled to negotiate with the corrupt conductors. Eventually we took a risk, only to find the exit open and unguarded, and so went out into a dusty Zhangjiajie afternoon unhindered by anyone except Judy herself. Zhangjiajie City

Zhangjiajie was rather on a par with Jishou. Both cities taken at a glance were about the same size, although Zhangjiajie's proximity to the park gives it a slight advantage as a tourist destination in its own right, which resulted in a more bustling atmosphere and more obvious sightseeing possibilities. A huge pagoda presided over the city from a hilltop; wide busy mercantile burrows spun webs into the interior of the concentrated downtown area, which a short bus-ride from the station entered us into. It was late afternoon, Hamish and I were keen for a little exploration, but Bonnie was already being pestered by Judy about getting to the park, still an hour away by minivan. It was past the regular tourist hours, and bus drivers were keen on a foreigner's markup for a special trip to the scenic area. Judy demanded instant decisions as Hamish and I discussed options with Bonnie - I broke with common politesse and directly asked her to shut up. The reprimand came as something of a surprise to her. Later, on the expensive bus we decided on taking to the park, I confronted her about her attitude - she coldly delivered an unforgettable line: 'I could accept a Chinese man, no matter how bad, but I could never accept a foreigner.' Giving up, I glowered out the window at the light dimming on the hills. There were so many evidences of humanity marked on the land, remote shrub-covered slopes parted to reveal improbably old stairwells. No nature here that wasn't inhabited somehow. Judy's racial intolerance continued at the hotel: her family friend gave the girls a free room, but charged us only at Judy's insistence that we could afford it. Bonnie tried to have a quiet word with her in private, but was only told that she was becoming more and more un-Chinese, and that all of her friends were disappointed with her. She would have stayed in her hotel room all night if Hamish and I hadn't been hungry, necessitating her invitation to dinner downstairs, undercooked and overpriced. Our only escape was a lamplit walk along the roadside some hours later; a crescent of hotels and tourist stores which curled towards the park entrance, which was locked for the evening. It was as if a street of cheap kitset models had been tumbled carelessly out on the forest and rock. The light from imitation dynastic lanterns shadowed little tents of Chinese travellers, plastic round dining tables huddled about TV sets enabled with Karaoke microphones, they beckoned for us to sit with them but we preferred instead to sit on the rocks around the gate, looking into the park. We talked in schoolday dialogues that night, sixteen again, echoed the naivety of plans made before we'd even explored our own city, there in the atmosphere of a jungled Chinese cultivated land, one other thing that happened on Chinese soil, Hamish and I. The Park The entrance fee was higher than expected, just the first indication that a natural wonder had been turned into something less of a spectacle and more of a massive trinket store. A gloomy walk along the riverside through the brush led to a small bridge frequented by a group of monkeys, feed for which could be bought from a peanut shack. We tossed a few nuts at the primates and ate the rest ourselves. After some moments, the park trees left off for a kind of organic reception hall, a pleasant grassy cove at the base of the nearest mountain group. Huang Shan was the most obvious candidate for climbing, although chairlifts were available for less adventurous travellers to achieve the height. Zhangjiajie park is actually enormous, covering acres through which outdoor-types can tramp and hike and camp for days. I must confess not to be the rugged backpacker, and am actually of the persuasion that more about China can be learned from watching families at McDonald's than can be found at the top of her mountains, particularly those with colourful imitation temple shops doing business on the summits. Hamish and I had both had our share of bush-trekking as Cub Scouts in Auckland's Waitakere Ranges, where both of us spent some part of our childhoods, and to be frank, even Zhangjiajie's gargantuan columns of rock held momentary interest. It was fantastic to be in this remarkable place, the scenery was spectacular indeed, the mountains were very high. I suppose I just am not of the disposition to have my awe at nature's splendour in any way exacerbated by being uncomfortable in the woods. In some ways, Zhangjiajie didn't rate highly against the Waitaks, the deep clean smell and vivid greens of the New Zealand native forest - Zhangjiajie was a tour package, hundreds of Chinese travel there each year, spend a lot, are told what to be impressed by, and leave with the same satisfaction as a television viewer. We were there with similar motivation, not intending to go deep into the untouched wilderness (as if any wilderness could be untouched in central China), wanting to see the pillars and go home. However, our appreciation of the park was limited by two major factors - firstly, the incessant souvenir shops and offers to be carried to the top of the mountain instead of climbing the (not very steep or difficult) path, and secondly, by Judy. Judy's inability

to hold back her racial slurs became a source of no little frustration

during the climb. Fortunately her tolerance for us was even slighter than

her own interest in reaching the summit of a tourist attraction she'd seen

before, so within the first hour she gave up and turned back for the hotel.

To Hamish, Bonnie and I, this was the providential stroke that made actual

enjoyment of the rest of the day possible. The view was, after all, extraordinary,

as we made our way above the mists and saw down through valley upon valley

of rock shards thrusting out from the canopy.

At the bottom again, we lazed on the grass by the river watching the tourists pass - there was a lot more of the park to see, river trips, other mountains to climb... I took close up photographs of Bonnie's engagement ring around her fingers spread out incautiously over the clover. In the warmth of the afternoon, the majesty of Zhangjiajie was a bore - we only had one more day to spend in town, and we all resolved to spend it in the city itself rather than in the reserve. It was to be a slow evening, anyway - reunited with Judy, we wandered the rows of cheap restaurants, trying to find one that didn't require the killing of the dish before consuming it - cages of toads, turtles, pheasants and snakes did little for the appetite, the pulling out of a meat cleaver when we asked if they had a favourite chicken recipe - snails in garlic seemed the most humane meal, although half were pregnant with tiny shells - and fortunately, the chosen venue had tomato and egg which seemed divine fare. Back in the City It was with great relief that Judy unexpectedly leapt from the bus when pulling into one of the last stops back to the city centre - apparently, she'd told Bonnie she'd decided to go home for a couple of days, leaving the three of us thankfully alone for the remainder of our trip. We snagged a map and set off through the back streets, attempting to pick up a feel for the city within the few hours we had left. Zhangjiajie city is a small and rather typical Hunanese town as far as the central city area goes. Dark suited locals squatted on diner stools and outside garages, dusty tiled roads, gray and lime green dim streets, brick dust and puddles. Many streets were picturesque with beautiful lines of trees stretched alongside soft quiet grey roadside walls, white tiled blocks reaching out above the bushy clumps of branches. There were open balconies, straw hats, merchants squatting at the roadside cleaning shoes or selling flat baskets of vegetables. It took a long time to select a restaurant with appealing items on the menu - not that we we faint hearted when it came to foreign food, but that the monotony of the dishes on offer made it difficult to search out anything pleasingly suitable for lunch. We finally hit upon a small corner joint which sold a great duck hotpot, although we had to suffer double the price - Bonnie was pulled aside and instructed as to how best to make the most expensive markups on the goods she introduced her foreign tourist guests to - 'be sure to make a good profit for China', they told her. It would have been inappropriate to educate them on the point that Bonnie was poised to marry one of them. In the last hours before leaving Zhangjiajie, Hamish and I decided to take the chance to climb the mountain where the pagoda we'd seen from the train stood. Navigating the streets at the base of the slope was difficult enough to make us miss that attraction and instead unwittingly let ourselves into a memorial site which was actually higher than the pagoda and therefore not a bad swap. From the peak, we had a good vista of the city, and as we watched the cityscape recede over a reddish beer as the train pulled away from the station, the newly acquired Wang Fei recording, Fu Zao, which we'd found in an unlikely little store on a back street in town, made a quirky backdrop to a funny mixture of a city, a weird placing of tourist prosperity and the old habits of poverty, a village as much a victim as a beneficiary of China's economic reforms. |