Welcome to my essay section. Now, I may only be a history major, but I'm going to try to write like a sociology person and deeply analyze all these aspects of our culture. So read on and be sure to tell me what you think. Too many people quickly dismiss vampires as a product of fiction, or superstition or cultism. However, I have found they are a much more useful tool; vampires directly correlate with the society that they appear in. For instance, in plague-ravished Europe, they were seen as evil bearers of diseases. However, some 500 years later, they are considered very sexual beings. Certainly they may have the power to kill you, but they are not the demon-like rotting corpses they once were. For heaven's sakes, they are on Sesame Street, and on boxes of cereal (read Step 7 for a closer look at vampires in modern culture). What does that mean? Well, in this series of essays, I hope to address vampires from all their different aspects, past and present, and shed some light on these creatures and legitimize them as icons of the human world.

Vampires–An Urban Legend of the Middle Ages? Did people actually believe that vampires existed, or were they just a campfire ghost story? This essay explores the similiarities between vampire folklore and modern-day urban legends.

Women in the Vampire World My first essay for this web page, it examines how women are portrayed as vampires, as victims and how they look at vampires as an audience.

The Problem with Immortality Why we secretly long to to be vampires and the problems vampires face with living forever.

Visually Identifying the Vampire What makes a vampire look like a vampire? Here are 9 characteristic traits that make vampire images easily identifiable.

Vampire Princess Miyu

Kyuuketsuki Miyu

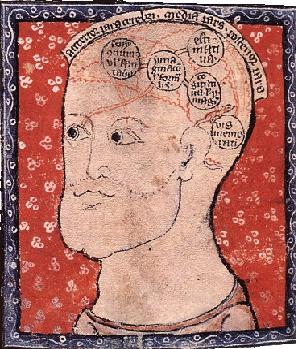

Picture provided by: Countess. Click picture for link.

In modern society, vampires are relegated to an icon at Halloween, or at most, a symbol of an alternate lifestyle, which is seen as anything from a fad to a cult religion. However, during the Middle Ages, vampires were seen as a very real threat to mankind. As the werewolf was a symbol of the very real fear of animal attack, so too the vampire took on– or was created to be– a symbol for another threat in the lives of the people. This threat, represented by the vampire, was of nature out of control, specifically natural cycles. The most blatant of these cycles was that of death and birth, but the vampire too played a role in weather and farming seasons. While no one could control the amount of rain or illnesses that swept through the villages, people found that they could control vampires. When rituals failed to prevent a natural disaster, the people went through more elaborate practices, often having to repeat them many times, until the disaster ceased. With something tangible, like a dead body, to both blame and manipulate, the people were able to put some semblance of control on nature.

Before further exploring the factors behind the vampire, the aspects associated with it must first be defined. To begin with, the vampire must be defined and classified.

Vampire accounts are what folklorists call legends, that is, stories told as true and set in the post-creation world.1

While it may seem like splitting hairs when it comes to referring to the vampire as a legend or myth or folktale, it is relatively important to nail down the proper term. Myth, to a folklorist or anthropologist, refers to a religious concept dealing with the creation of the world.2 In the vernacular it is misused, and is synonymous for fantasy or untruth. The vampire fits neither of these interpretations. And because "folklore" is also associated with a story that is to be taken as untrue, it may not be used. "Legend," therefore, is the only alternative left for use.

Vampires tend to be difficult to understand and define, as the European variety is sometimes confused with vampire-like creatures in other cultures. Legendary vampires– those dating before 1730– often overlap characteristics with literary vampires, and at other times completely contradict them. The modern scholar must set aside all his or her previous concepts of the vampire, especially those gathered from books or film, and begin afresh with the simplest, most universal definition of a vampire.

A vampire is a dead body which continues to live in the grave, which it leaves, however, by night, for the purpose of sucking blood of the living, whereby it is nourished and preserved in good condition, instead of becoming decomposed like other dead bodies.3

There are other characteristics of the European vampire, but these traits vary by region, country, religious and cultural background, village and even individual. This definition, though, provides the core features of the European vampire.

In this definition of a vampire, there is little difference between the European vampire and vampires in other cultures across the world.

With a persistent sense of the fitting (and a deplorable sense of taxonomy), European scholars have commonly referred to these, and to the undead in far-off cultures– for example, China, Indonesia, the Philippines– as "vampires" as well. There are such creatures everywhere in the world, is seems, in a variety of disparate cultures....4

Scholars, as is pointed out here, use the word "vampire" too freely when labeling similar phenomena across cultures. While a vampire may be any dead body which refuses to stay dead, it might be fitting to refine the definition to any dead body in Eastern Europe which refuses to stay dead. This would lead to much less confusion when vampire characteristics are discussed; generally European vampires are alike, whereas international vampires vary greatly from these and from each other.

The European vampire did not exist in all parts of Europe. It had a range roughly equal to modern Eastern Europe.

Among the East Slavs, the vampire is well known to the Ukrainians. The Russians knew it by its name in former times (from the eleventh to fifteenth centuries). The vampire tradition is well documented among the West Slavs– the Czechs, Poles and particularly the Kasubs, who live at the mouth of the Vistula River– and among the South Slavs– Macedonians, Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.5

[See map for additional reference.] This provides an almost complete picture of the countries involved in the vampire myth, with the exception of Greece, Romania, Hungary and Albania, where the vampire also appeared.

As was mentioned above, the vampire possibly dates back to the eleventh century. A generally accepted date of the origin of the word "vampire" is 1047 in Russia.6 In a historical account, a Russian prince is referred to as a "lichezy upir" or "wicked vampire," according to its modern translation.7 There is, however, a problem with the assumption that "upir" meant "vampire" in that context. Little, if any, evidence points to the Slavs or others referring to living people as vampires. Furthermore, people of noble birth are almost always excluded from suspicion of being vampires.8 This insult appears to have been directed at a prince who was doing something wicked while still alive, all but disproving that "upir" is being used, in this case, to mean "vampire" as a malicious, though dead, body.

Disproving the Russian reference to the word "vampire" collapses almost all hope of dating the start of the vampire legend. Without this one reference, there is no written proof that the vampire legends began before the late seventeenth century. Of course folklorists know that the vampire legends existed long before they were written down, but it makes it hard to define when they began. To pinpoint the best frame of time to work with, it is necessary to know a little history of the Balkan region.

[Slavic people] began to move southward from Central Europe into the Danube Valley in significant numbers in the fourth century A.D. The process was a gradual drift and infiltration rather than a sudden invasion. By the sixth century the Slavs firmly occupied the Danube Basin and began to cross the Balkans.9

Taking the common theory– that the origin of the word "vampire" comes from the Slavs– as truth, then 500 A.D. is the earliest possible time for the concept of the vampire to emerge.10 This, however, is almost certainly too premature as the vampire requires a number of variables to be present, not least among them some measure of stability. There was likely little time to develop legends while the Slavic people were migrating, then later setting up states of their own.

These Slavic newcomers organized a number of powerful empires in the Balkans during the medieval period (before 800 A.D.). The first of these was the creation of the Bulgarians, a people who were not Slavs, but rather Finno-Tatars related to the Huns. Within a comparatively short time the Bulgarian minority was assimilated and became Slavic in everything but name. [The Serbs and Bulgarian Slavs] organized great, though short-lived medieval kingdoms which borrowed their culture from Byzantium. In contrast, the Slovenes and Croatians, because of their position in the western part of the peninsula, became subjects of the Holy Roman Empire and were influenced by Rome rather than Constantinople in their cultural development.11

The Slavic tribes did not find cohesion until 800-900 A.D. with the wide adoption of Orthodoxy and two centuries later they managed to form into two states.12 These states began collapsing and warring among themselves after just a few generations of self-rule. "We may conclude that the entire Balkan peninsula on the eve of the Turkish invasion was socially as well as politically ripe for conquest."13 By 1480 the Turks controlled the Balkans as far north as Serbia and Wallachia (part of modern-day Romania) and by 1683 they controlled all of present-day Romania and part of Croatia and Hungary. [See map for additional reference.]

Because of certain conditions that existed among the occupied Slavs, it is likely that the vampire concept developed during this time. Secondly, the date should be placed after the Black Plague. It was likely that after dealing with this devastating pestilence that the image of the vampire as a harbinger of the plague began. Averaging between the Plague in 1348 and the Turkish conquest of the 1400's,14 a probable guess to the start of the vampire concept was around 1400.

Though less of a guessing game than the start date of the vampire, the end date is no less arbitrary. Though the vampire himself has never disappeared, his status as a real, legendary creature has. Certainly no one in the modern world believes that their dead grandmother could get out of the grave and attack them. At what point did this change? Where should the measure of this change be recorded? In some very rural Slavic areas this legendary vampire still exists, but over the majority of Eastern Europe it has long since been laid to rest. Almost any date, therefore, is as good as another. It was around 1730 that the declining Ottoman empire lost Serbia and Wallachia to the Austrian Empire. Western Europeans were first introduced to the vampire legend when the Austrian forces returned home with stories and report of the undecomposed dead. Shortly thereafter a wave of vampire hysteria swept over all of Europe. Just as quickly it petered out and the literary vampire was born. Taken out of Eastern Europe it becomes merely a generic icon for any culture's use. And the vampire's quick acceptance and quick disappearance in Western Europe points to it merely being a fad and not an entrenched cultural icon, as it was in Eastern Europe.

With the vampire defined as a dead body, classified as a legend, limited to Eastern Europe and dated between 1400 and 1730, there only remains one more issue to address before inspecting the function of the vampire further: the unique characteristics of Eastern Europe that allowed them– or even encouraged them– to use vampires as a means of controlling nature. There are certain characteristics among the Eastern European countries that make them different from Western Europe, and some of these characteristics are what allowed Eastern Europe to develop the vampire when Western Europe did not. The most notable difference were the Ottoman Turks. Certainly this was not the only factor– after all, Poland, Russia and Czechoslovakia had vampires, though lesser in intensity than in the Balkan states– but it was a powerful one. And the Turks influenced the population through governing, and indirectly through their policy making.

In tolerating the religions of the non-Muslims [the Ottoman Empire] also accepted their usages and customs. This was implemented by permitting non-Muslim subjects to organize into communities with their own ecclesiastical leaders.15This illustrates one of the most significant factors in the occupied territories– although they were allowed to keep their own religions and religious leaders within their own communities, no one religion controlled both the church and the state, unlike Western Europe where almost every country had to answer to the Church in Rome. This, of course, greatly affected the amount of power that the church had.

Closely related to this was how the Ottomans viewed their subjects and how their subjects organized themselves.

The Ottoman authorities divided their subjects not into Greeks or Bulgarians or Romanians, but rather into the following [groupings]: Orthodox, Gregorian Armenian, Roman Catholic, Jewish and Protestant.16The land of the Ottoman occupation was diverse and many religions coexisted side-by-side without the strife that was often prevalent in Western Europe. This is relevant when it is noted that much of the vampire myth comes from gypsies, a normally marginalized group of people in society. It would seem, from the survival of their vampire myths, that there was a heavy exchange between gypsies and local people.

Another factor that contributed to the vampire myth was a de-urbanization of Slavic people. This move from the cities to the country was also a result of the Ottoman occupation.

...There was a common tendency among the Balkan Christians to move out of the urban centers in order to avoid the Turkish officials and garrisons. When a Serb, Romanian, or Bulgarian went into a town in his native land he found himself a foreigner.17As there is a rich legacy of folklore among the peoples of Appalachia, so too there is a wealth of myth among the occupied Slavs who were forced to retreat from their cities. There was also another condition that existed along with the rural factor that made a fertile ground for folklore.

The Balkan people themselves have left few records of this period (Ottoman occupation) of their history. Having lost their ruling class, which alone was educated and articulate, they were left leaderless, anonymous and silent. Even their clergymen were largely illiterate.18Coupled with a lack of supreme church control, a retreat from the centers of Muslim government and a lack of a natural ruling class in aristocrats or former noblemen, the people were left largely to themselves, and without literacy, to their own imaginations and oral traditions.

The superficiality of Turkish influence allowed the Balkan people to develop their respective cultures freely. In each case they made their most important contributions in their folk literature. This was usually anonymous, composed in the vernacular and passed on from generation to generation by word of mouth. 19This ability not only to cultivate but to preserve folklore and legends allowed the vampire to be born.

Though there were resources for folk tales, it takes a few more elements to turn those fictional tales into vampires, which were believed to be real. There are two factors that probably endowed the vampire with life, rather than keeping it relegated to a mere folktale. One was the penchant for the people of the Balkans to personify everything.

Certain characteristics are common to all Balkan folk songs. Most striking is the personification of nature. Mountain peaks dispute each other; plants and animals hold allegorical conversations; and birds bring aid, give advice and deliver love messages.20There is, obviously, more to this than the simple personification of inanimate objects, though this certainly points to the ease with which the vampire was accepted by the people of the Balkans as a natural phenomenon.

The final obvious factor for the Balkan to develop vampires was the plague. Though this was prevalent throughout Europe, it remained in Eastern Europe, giving the vampire reason to stay once he was developed.

One of the most appalling results of Turkish obscurantism was the persistence of the bubonic plague in the Ottoman Empire for over a century after it had petered out in the West. Following the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century the plague continued to devastate Western Europe until the eighteenth century. Then is receded to the Eastern European lands, and until the mid-nineteenth century the Ottoman Empire suffered cruelly from the effects of this dread disease.21This continual wave of contagious disease as well as an affinity for portraying passive objects as real and alive surely formed the basis of the need and the potential for the vampire.

Certainly there was ample opportunity, basis and need for a being that could be controlled in the ways that nature could not. But in what ways did the vampire fulfill that role? How was he connected to nature and the life cycles? Once created, how was he controlled? An in depth look at these questions will, if not answer them, provide a better understanding of the rural, uneducated people of Eastern Europe and the beliefs behind the vampire.

It is hard to say, with any degree of certainty, what exactly spurred the creation of a vampire myth. As mentioned in the introduction, there were many factors at work in Eastern Europe that would certainly allow for a vampire superstition to take shape. However, it is unclear which of these lead to his actual formation. While it may be hard to point out an exact cause for vampires, it can be determined, with some measure of certainty, which factors contributed to the growth and continuation of a vampire myth.

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor worship was part of the practices found in the pagan religions that predated Christianity in the Balkans. Later these pagan practices became refined down into what is generally labeled "superstition," and were practiced alongside and in concert with Christian beliefs.22 It is partly because of this coexistence of superstition and Christianity that vampires were able to come about and persist. Ancestor worship too found a niche in Christian beliefs, with the formation of such religious holidays as All Hallow's Eve and All Soul's Day, when offerings were left for the spirits of the dead, who were thought to cross over from the other realm to the world of the living.23

The people of Eastern Europe had superstitions concerning their dead before the vampire was introduced. Many of the beliefs concerning the dead and spirits were later transferred and incorporated into vampire myths. Some of these concerned the harm that the dead could inflict upon the living.

In Russia and Germany there is the belief that the open eyes of a corpse can draw someone into the grave.24

This is very similar to the situation that occurs when vampires appear; oftentimes the simple sight of the vampire can claim victims.

Another cross-over trait between spirits and vampires is their thirst for liquids, blood being the most notable. Alan Dundes suggests that aging and dying were correlated to dehydrating; the same way a ripe plum shrivels into a prune. He further hypothesizes that people, therefore, assumed that the dead would be thirsty since they are dried out.25 This belief led to the practice of pouring libations on graves to appease the dead. This belief was later applied to vampires who went looking for their offerings.

A third commonality between spirits of old and vampires was their propensity for exacting revenge, usually due to neglect. Burial customs everywhere demand that a certain amount of care and respect is shown to the dead. When the dead are not given their dues, for whatever reason, it is generally believed that the deceased's spirit will make mischief or bring harm to others to show his displeasure.

Generally it is considered dangerous for a corpse to be left unattended. ...Greek revenants [are] dead people who died alone and had no one there to take care of them. ...Among the Gypsies, "if someone dies unseen" he becomes a vampire, and among the Finns it is enough that a corpse is neglected for it to return to harm the living.26

It would seem that revenge alone is enough to animate a corpse.

Vampires were not born from ancestor worship alone. Spirits and bodies are two different things entirely. But the foundation for the vampire is clearly laid. Spirits demanded respect and liquid offerings; without these they could grow violent and cause others to die. The vampires is all of these things. Indeed, he seems to replace spirit worship, as it is the body that is given food and drink to keep it appeased. Eventually the Balkan people moved the intangible concept of the wicked spirit into the wicked body, the vampire, but what led them to this is not entirely clear.

The Plague

Rampant and deadly diseases had a large impact on how medieval people viewed the world.

Lacking a proper grounding in physiology, pathology, and immunology, how are people to account for disease and death? The common course, as we shall see, is to blame death on the dead, who are apt to be observed closely for clues as to how they accomplish their mischief.27

Vampires continued the tradition of spirits by bringing death from beyond the grave. Due to his physical presence, however, the vampire was accused of bringing death in a more widespread manner.

To understand how a walking corpse may bring death to the living, it must first be seen how an unanimated corpse, through no magical powers, brought death by means of disease.

The violence of this disease was such that the sick communicated it to the healthy who came near them, just as a fire catches anything dry or oily near it. And it went even further. To speak to or go near the sick brought the infection and a common death to the living; and moreover to touch the clothes or anything else the sick person had touched or wore gave the disease to the person touching.28Modern-day science can explain the transmission of diseases by germs, or in the case of the Black Plague mentioned above, through parasites such as fleas. To medieval people who had no such explanation, it appeared that the dead themselves were the source of the illness.

Once it was established that dead bodies– as opposed to spirits of the dead– were the cause of death, the vampire became the icon for the plague.

The stench of the vampire, by the way, is one aspect of the nexus between vampirism and the plague. Now, foul smells were commonly associated with disease, also as a cause, perhaps because people reasoned that, since corpses smelled bad, bad smells must be the cause of death and disease.29

An interesting progression can be seen in the logic of medieval people: corpses, by just being, can cause others to fall ill and die. These corpses smell bad, as do people who are stricken with open sores, caused by the Black Plague. It appears then that smells cause, or at least denote plague. So when bodies are dug up that are accused of being vampiric, and they smell foul, it is logical to conclude that the dead body in question, the vampire, is likely causing the plague.

There is a tricky situation in this logic; which came first, the chicken or the egg? It is hard to judge whether the vampire was invented to explain plagues, or whether plagues were added as another trait to the already existent vampire.

...Vampirism occurs as an epidemic... as the first person who died is held responsible for the deaths that followed: post hoc, ergo propter hoc.30

In this situation, the first to die of the plague is accused of spreading it to others, but a catch to this is that the person who got it first must have gotten it from someone else. It, therefore, makes it impossible to ascertain whether plague or vampires came first.

Likely Suspects

Although ancestor worship probably forms the basis of the vampire myth, and the plague both helped it form and continued it, one element remains to be explored– those people who, in death, became vampires. Without someone to become a vampire, there would have been no vampires. And not just anyone could become a vampire; as there were rules governing how the vampire acted, so too were there rules governing who became a vampire.

One of the few hard and fast traits of the vampire is that he is from peasant stock.31 The wealthy and nobles– few though they were in this time period in the Balkans– were never accused of vampirism. Peasants both fostered the belief in the vampire and were subjected to him– some being vampire victims while others were victims to the vampire curse.

Vampire victims, other than being peasant, had no other limitations. Vampires come out of their graves in the nighttime, rush upon people sleeping in their beds and destroy them. They attack men, women and children, sparing neither age nor sex.32

People who would become vampires, however, had a number of characteristics that distinguished them from those who would be victims.33 Some would-be vampires truly were victims to the curse of vampirism, as they had no control over what made them vampires.

Frequently people become revenants through no fault of their own, as when they are conceived during a holy period, according to the Church calendar, or when they are the illegitimate offspring of illegitimate parents. Indeed, in Romania it is reported that merely being the seventh child in a family is apt to cause one to become a revenant.34

The second class of vampire is similar to the one above; in it are those who were born with abnormalities. Although they, like those conceived on church holidays, etc. are unable to change their circumstances, they are fit to be in a second category. Stigmas placed on social faux pas– as those above– are much more likely to change, whereas humankind has had a long history in marginalizing or blaming those who are physically different than those in the majority.

Even within the category for the physically different there are rules that are very specific. For instance, not included in this category are lepers, the mentally ill or the lame. Those who are singled out to become vampires have certain traits that were meaningful to those involved in vampire folklore.

Often potential revenants can be identified at birth, usually by some abnormality, some defect, as when a child is born with teeth. Similarly suspicious are children with an extra nipple; with a lack of cartilage in the nose, or a split lower lip; or with features that are viewed as bestial, such as fur down the front or back or with a tail-like extension of the spine, especially if it is covered with fur.35

Although there is room for speculation as to what an extra nipple might mean in a vampire myth, children being born with teeth has obvious implications, as vampires are known for their sharp teeth and biting. Likewise fur or a tail would point to werewolves, a close cousin and predecessor of vampires.

The final category for those likely to become a vampire are those who commit crimes against man or religion.

...Categories of revenants: the godless (people of a different faith are included here too!), evildoers, suicides, in addition sorcerers, witches and werewolves; among the Bulgarians the group is expanded by robbers, highwaymen, arsonists, prostitutes, deceitful and treacherous barmaids and other dishonorable people.36

This is certainly the broadest– if not most abundant– category for potential vampires. People on the fringes of society and the church not only made an easy target for blame, but a logical one. Since the vampire causes so much harm, then it must follow that he comes from those people who caused harm in life.

Many factors existed in the Balkans that allowed for the possibility of the vampire. Three factors lead to the vampire's "birth:" a historic tradition of blaming death on the dead, a need to explain present disasters on something, and an inexhaustible supply potential vampires and vampire victims to perpetuate the myth. It is the combination of these factors, rather than any one thing, that created the vampire in the Balkans.

A vampire's actions and characteristics are very much like those of a living person. A vampire is "born," he feeds, procreates and "dies." Once there is a reason for vampires to be, they appear. But vampires do not simply crop up like weeds, then disappear when there is no longer a threat. The vampire myth is a highly structured set of guidelines that vampires must follow. While these rules governing a vampire's characteristics are open to interpretation, many of them can be seen as a direct correlation between vampires and a perversity of man or nature.

Birth

When the need arises, a vampire is "born." As discussed before, vampires usually appear simultaneously with a plague, drought fierce storms, famines, or livestock illness.37 Their "birth" is an ordered one. Vampires do not appear out of nowhere, but come out of their graves.

Death is a reversal of the birth act leading to a return to the pre-natal existence within the maternal womb.38The maternal womb, in this case, is the earth itself, considered the mother of all and life giver. This both allows the dead body to come back to life, to be "born" again, and ties it to nature.

The first act of a newly "born" vampire was to return to his family, and almost always proceed to attack them. "The Slavic vampire's hostility was directed almost entirely at his next of kin."39 There are many possible reasons behind this act. The vampire may have cause to see revenge against his family.

It was much feared that a member of one's house would become a vampire. In spite of this, the Greek habit of cursing the dead seems to almost invite this.40Trouble between family members and the vampire would, in all likelihood, cause the vampire to come back to attack those who had wounded him. It also must not be forgotten that a vampire's kin are his "blood" relatives; the vampire may be attracted to his family for this very reason. If the vampire's blood (life) is deficient, then he might wish to take blood (life) from those who have blood that is the same as his. The vampire is also a mockery of human life– he seems to be alive, but he isn't; he "lives" a life opposite that of a living person. By the vampire being a creature of opposites, it would seem logical that he should kill his family rather than love them. And last, the vampire followed a very logical pattern; the vampire, carrier of– and symbolic of– the plague, killed his family first simply because they had been closest to the diseased deceased. Anyone who has had a cold can witness how it is spread among family members, then travels out to friends and colleagues. As was shown before, medieval people understood that disease was communicable. It is reasonable that they should accuse the vampire of attacking its family simply because the death of whole families was witnessed and needed explaining.

Feeding

Vampires commonly had three options available to them for a meal: food, blood or milk. Food was most usually procured directly from family members, usually in the form of offerings, which might include the funerary feast.

[The wife of a clergyman] had been in the habit of visiting the grave [of her late husband].... There she spent many hours. At every visit she brought provisions– chickens, pigeonpies [sic], fruit, bread, wine and various other dainties– which she left behind on the grave.41

The act of sacrificing to the dead was continued with vampires. In the case of vampires, the meal was done less out of devotion and more in the hopes that the vampire would occupy himself with food, rather than living people.42

...Millet must be scattered over the vampire's body, as the vampire delays his exit from the tomb until each grain of millet has been eaten or counted.43

Although food was sometimes left at the grave or buried with a corpse, this was not a great deterrent of vampire attacks, nor did it seem to be the vampire's meal of choice.

Perhaps the single most notorious characteristic of the vampire is his penchant for drinking blood. As was mentioned in chapter one, "...all the dead in the Indo-European and Semitic world are considered thirsty, not just vampires."44 One reason behind this is through the logical observation that the elderly and the dead wrinkle and appear to dry out like fruit. Therefore, the dead would be thirsty, as plants withered from drought are thirsty. A less apparent answer is that liquids are life. The dead's craving for liquids is not merely to regain the appearance of youth, but to give them life again.

While some dead were content with any liquid offered, vampires almost always choose blood.

Some believed that the soul lived within the blood; others, more simply, that it was source of life.45

Again, the reasoning is clear: blood is a person's life, therefore life should be (or could be) gained by taking blood. The blood of the living was so vital to survival that vampires would never attack a body already dead.

It also bears mentioning that the vampire's blood-drinking habits are not only a perversity of human morality, but also of Christianity. At Communion, the priest recites the following before giving wine– symbolic of blood– to the congregation:

The Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, which was shed for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life. Drink this in remembrance that Christ's Blood was shed for thee and be thankful.46

In drinking blood, the vampire took communion. But rather than drinking Christ's immortal blood, the vampire drinks the blood of the mortal. Rather enjoying his eternal life in the hereafter, he spends it on earth.

To point back to the grave as a form of "birth," one curious characteristic of the vampire should be noted– The vampire may choose to drink milk rather than blood. "Blood and milk are inextricably linked as both are donors of the life-stuff,"47 so it may be for this reason that vampires can just as easily live off milk as blood. Also, drinking milk seems logical for a vampire who was just "born." In the case of blood drinking, the vampire's sucking points to this infantile practice– it is important to note that the vampire sucks rather than laps up blood.

Procreation

Second only to his appetite for blood is the vampire's desire for sex. Sometimes feeding and sex appear linked, as the vampire causes his partner to waste away while he presumably grows stronger.

The vampire of folklore is a sexual creature, and his sexuality is obsessive– indeed, in Yugoslavia, when he is not sucking blood, he is apt to wear out his widow with his intentions, so that she too pines away, much like his other victims.48In this one case alone there is both the vampire's tendency to attack his family, and his ravenous hunger, here expressed through his sex drive.

Interestingly enough, however, here the vampire has a second, opposite reaction. The vampire is just as likely to return to his widow or lover to pursue relations, with her consent, that are not harmful. In fact, these trysts can go on so long that the woman can conceive and bear a child by the vampire.

...Gypsies believe that a vampire can come to his wife at night and procreate a "child...." In Kosovo-Methoija the Orthodox Gypsies call such a child, supposed to be born of a Gypsy mother and vampire father through their intercourse after the husband's death, "Vampirić."49The vampire can even appear to be a loving and doting mate, contrary to his otherwise ruthless nature.

There is also a belief that the vampire helps his wife in her housework, winds the thread while she is weaving, threads the cotton through the eye of a needle as she sews, talks with her, and eats the sweets she has prepared for him. There are some vampires who, where they come into their relatives' homes, bring with them little wax candles nearly burned out. Such a one brings washing-soap and leaves it in the cupboard where the flour is kept, knocks on the chimney and tidies up things. The vampire does no harm to its relations.50Rather than his usual style of living his life in reverse of a living man's, here the vampire seems very normal, very alive. Indeed, why would any family member expose this loving husband. It may have been believed that the vampire, in this way, could pass himself off as human to avoid detection and prolong his own "life." This undercover life could then allow him easy access to normal devilry that he likes to accomplish.

Thirty years since a stranger arrived in this village, established himself, and married a wife with whom he lived on very good terms, she making but one complaint, that her husband absented himself from the conjugal roof [sic] every night and all night.51Here the vampire passes himself off as a man, but cannot escape his vampire nature, and so he leaves his wife at night to do, presumably, harm to either livestock or man.

The only thing that might possibly account for this unusual behavior, both by the living and the dead, is ancestor worship. Spirits of the dead who were given their due reverence were often seen as benign. On such holidays as All Souls' Day, food was prepared for the dead and chairs were set out for them, and they were generally welcomed into the house.52 The vampire may have been viewed as other (unanimated) dead were, and given a proper welcome and treated like he was still part of the family.

Having created the vampire to explain what caused a disruption in nature, such as plagues and famine, and having given the vampire the means to accomplish his malicious deeds– eternal "life" through blood drinking– it now falls to people to devise a way to get rid of that thing– the vampire– which brings misery to them. Like the creation of the vampire, and his exploits, "killing" the vampire was symbolic, logical and a mix of folkloric and Christian remedies.

Burial Ritual

How people took care of the dead harkens back, once again, to ancestor worship. Few, if any, peoples have shown no respect to the dead, both before and after burial.53 It is, then, not surprising that the Slavic people too should exert a certain amount of care when handling and burying their dead. When the threat of vampires exist, it would be important to avoid them at all costs. So to begin combating the vampire, preventive measures must be taken.

There were a variety of preventive measures, all aimed at keeping a corpse from rising in its grave. Some of these were done using folk remedies, other Christian remedies and finally people used common sense. They were used alone, and in conjunction with other methods. Like vampire characteristics, the methods of choice depended on the people, region and dominant religion.

As was mentioned with ancestor worship, vampires– like their spirit predecessors before them– were fed to try and bribe them into not rising from the grave.

Food was buried with the corpse– presumably to assuage any immediate pangs of hunger and satisfy the corpse within its own grave.54Millet was a common "offering" to a would-be vampire, perhaps because of its abundance in farming villages.

The vampire delays his exit from the tomb until each grain of millet has been eaten or counted.55

Along the lines of millet were stones of other small objects.

Small stones or grains of incense must be placed in all the extremities so that the vampire would have something to nibble upon awakening– thus diverting his attention from more succulent fare.56

Although this doesn't have the connotations of being an offering, as food is, the purpose here seems to be less along the lines of honoring and more toward keeping the vampire busy. Grain and rocks are both plentiful and small, and so are easy to put in a grave in sufficient numbers. In Western Europe there was a similar practice to deter witches, in which a dead dog or cat was laid on one's doorstep. The witch had to stop and count all the hairs on the animal before sunrise, lest she be caught.57 No adequate explanation has been given for why vampires and witches had a need to count things, but the fact that this act was widespread and crossed between various superstitious entities (witches and vampires), points to this belief being a folk remedy, and most likely predating vampires. When vampires appeared , this pre-existing act was copied from the prevention practices of another entity, most likely the witch, and applied to vampires. Another witch/demon remedy that was applied to vampires was the use of garlic. The use of garlic as protection so far predates vampires that how it accomplishes its deed of repelling evil has been lost. Like many superstitions which have been held over to modern day, tradition gave garlic its power, rather than a specific belief or reason.

A simple way to avoid vampires was to bury the body in such a way that it would become disoriented and have a difficult time finding its way out of its grave or into the village. The first way this may be accomplished is by burying the body face down.58 This either confuses a rising vampire as to which direction is up, or makes it impossible to get out of the coffin. The second method is to bury a body at a crossroads.

The suicide, totally frustrated and unhallowed in death, had the reputation of being a wanderer abroad, so it was considered essential that he should be buried at the crossroads. He would then have some difficulty in deciding which path to choose and his activities would be considerably delayed.59

This method was reserved almost exclusively for suicides and strangers, who were not allowed burial in a consecrated cemetery. There was a simple logic in removing the unwanted, potentially dangerous dead out of the village and away from where others lived. It also had health benefits as well– something the Romans were aware of when they passed a law that all cemeteries must be outside the city walls to prevent contamination and disease.

Another practical solution to walking corpses was to keep them from walking simply by tying their feet and legs together with a strong rope.60 Like garlic, another folk remedy for the vampire were wild roses or thorns. Although roses themselves may have had a magical use, they were probably used because of their thorns.

Wild thorny roses must be strung around the outside of the coffin in order to impede the vampire's progress out of the tomb.61

In this case the thorny vine is used as little more than a rope. In other cases, the thorn has an even greater role to play.

[Orthodox Gypsies] also have a custom of putting thorns into a hole in the grave from which it is though the vampire emerges, so that is pricks itself when it arises, and dies.62

Thorns, however, were used for other reasons than their ability to prick and draw blood.

It is the opinion of many that an hearbe that it is Whyt thorne... is neuer struken nor touched with any euyl from heaven. [sic]63

The thorns, then, are not only practical as a painful deterrent, but also have a mystical power to deter evil. This power almost certain predates Christianity– as Pliny, in 77 A.D. refers to thorns as being auspicious at weddings64 – but it was also reinforced by Christianity. "Under a thorn Our Savior was born"65 and "unto the Virgin Mary our Savior was he born, And on his head he wore a crown of thorn..."66 are two of the superstitions that connect the thorn to Christianity. The crown of thorns, a symbol Christ's suffering for man, was particularly relevant in the power of the thorn in keeping away evil.

Last– but not least– of the vampire prevention methods were those concerned solely with Christian rituals of symbols. Crosses were put into graves to immobilize potential vampires,67 or hung indoors to prevent vampires from entering.68 Various parts of the Bible were recited to help heal and prevent further vampire attacks,69 or copies of the Gospel (or verses from the Gospels) may be carried on the person to prevent attacks.70 One should also take communion, attend Mass and pray to prevent attacks by any evil entity.71

When prevention alone was not enough to deter the vampire, more drastic measures had to be devised.

Our sources, in Europe as elsewhere, show a remarkable unanimity on this point: the dead may bring us death. To prevent this we must lay them to rest properly, propitiate them, and, when all else fails, kill them a second time.72

Like everything else about the vampire, the method of killing him was not random, but a specific set of choices.

The most widely recognized method of killing a vampire was by staking him through the heart. As the heart is organ which contains and pumps blood, it is a logical place to strike to kill a vampire that sucks away blood and life. Among the ancient Egyptians, the heart was considered the seat of the soul and organ or both emotions and intelligence. It may be that this idea of the heart containing the soul carried over or was already existent in other cultures. As vampires were often believed to be animated by a soul still in the body,73 staking the heart may have been seen as a way of releasing the trapped soul from the body. Whether the heart itself held the soul, or the blood contained in the heart did, piercing the heart with a stake opened the heart and released the blood– and the soul.

Staking the heart also had another level of complexity, in that the stake itself was an important part of the ritual. While there were various beliefs as to what the stake should be made of, a large majority of stakes were made from a thorn tree. These included blackthorn, hawthorn, or whitethorn.74 This connects back to the belief that thorns prevent evil. Staking the heart both released the soul and pinned down evil.

The other known vampire remedies included dismemberment, decapitation and/ or burning.75 Few conclusions can be drawn from these acts other than the logic that no body (or body parts) means no vampire. Decapitation and dismemberment, however, may have been connected with punishment for crimes. Some criminals were beheaded, including traitors, who were also dismembered. Doing these acts to a corpse may have been symbolic of meting out justice or revenge on that (dead) person who has turned on his own family and murdered them. Burning was also an old and widely practiced method of killing witches.

The final step in combating the vampire was by thwarting it. Through most vampire victims died after a one-day illness– not counting those women who were the vampire's lover– a few were able to survive the initial attack. Although the victim lived through this first attack, survival was by no means guaranteed. In fact, only when certain steps were taken, certain measures applied, did the victim continue to live.

It would seem that it wasn't enough to merely kill the vampire to survive the illness his attack brought on. The only way to cure the illness was to consume part of the vampire.

When slaughtered, a great deal of blood pours from this voracious vampire, which is mixed with flour and made into bread. If this bread is eaten then one is free from vampire persecution.76

In some places vampire blood is substituted for his ashes and is drunk, rather than eaten. This "ritualistic vampirism" is the vampire's actions in reverse. Where the vampire takes life by drinking the victim's blood, so here the victim takes the vampire's life by drinking his blood, thus taking back that which was lost.

The significance of how the blood is consumed must not be forgotten either. The mixing of blood and bread is very much like the sacrament. In this case the blood and "body" of the vampire give (or restore) life. In the case of ashes, rather than blood, there is simply a reverse; the ashes represent the vampire's body while the water they are mixed in is the "blood."

The modern-day trend in our culture is to worship the new and scorn the old. For many years this was applied to anthropology and history, where, while looked at with interest, older or previous cultures were looked at as primitive. The idea behind cultural evolution was that people began with simple social groups and worked up into complex social structures, including patriarchy and monotheism.77 Because society evolved lineally, there was only one thing or the other. This way of thinking about past people has led to many misconceptions, including concerning those who believed in vampires.

It is true that Christianity rested very lightly on the mass of peasantry, which was illiterate and superstitious.78

Despite the rigor of the Christian proselytizers in stamping out the Old Religion, elements have survived in our times. The vampire is one of them.79

In neither of these examples is there room for superstition and Christianity to coexist, as it does today. The former quote hints that the peasants were not fully Christian, and that this is caused by their lack education– they are, therefore, primitive. In the second quote, superstitions are part of a pagan religion that slipped through the cracks and are left in more modern cultures like outdated clothes missed when the wardrobe was updated to something new.

In dealing with vampires, many elements of Christianity can be found. It seemed to be used about equally with older customs. In tracing vampire characteristics, as may can be attributed to Christian ideas as "pagan" ones. It would seem then that the Eastern European peasantry were not just slightly converted Christians, but true Christians who married older beliefs to new ones. A more correct view on how the two faiths coincide is as follows:

[Folklore] is strongest among the more pious adherents of the [Christian] religion. This is not at all surprising. Those who seek comfort and power in belief are often strengthened by the act of belief itself. The exact substance of the belief is not always significant.80

Here superstitious beliefs strengthen the belief in Christianity, not weaken it. Vampires are not a threat to Christianity; they give it a practical application. Priests did not fight against the belief in vampires, they fought against the vampires themselves. It must be thought that the people did not have two religions warring for their faith, but two religions joined to fight a common enemy.

If vampires were not just a traditional remnant of an archaic, pre-Christian religion, then what purpose did they serve? Paul Barber explains vampires as

...how people in pre-industrial cultures look at the processes and phenomena associated with death and the dissolution of the body. As it happens, their interpretations of such phenomena, from our perspective, are generally quite wrong. What makes them interesting, however, is that they are also usually coherent, cover all the data, and provide the rationale for some common practices that seem, at first glance, to be inexplicable.81

Vampires, then, are not "most amazing specters" located in "imaginations run riot" by peasants in "a backward country;" they were not "summoned forth by ignorance," nor were the vampire's activities an example of a "pagan holocaust." 82 Vampires existed because there was a need to explain the unexplainable. People used their knowledge of traditional methods and Christian practices, along with what they observed in the natural world to explain these events and try to control them.

It cannot truly be known what the medieval Eastern European people thought about when they integrated vampires into their lives. More than likely, the characteristics that were chosen for the vampire were as much selected by instinct as careful thought to the traditions of previous beliefs and the symbolism that can be inferred from connections with present day life and religion. Many still avoid the number thirteen when it occurs in daily activities; it is said that it is bad luck. Someone from outside Western society could point to the origin of the number's unluckiness from the Last Supper-- in which Jesus and his twelve disciples, who included Judas, made up thirteen, or from Jewish numerology, which places great importance on the number 7 and its multiples– 14, 21, etc.– and condemns anything that is less than perfect, such as 13. While these all have a basis into why thirteen is unlucky, people hardly think about them when they generalize the unluckiness of thirteen. Who is to say how much self-analysis the medieval people did on why they had vampires or why vampires did certain things, especially when there was a precedent for it. If it cannot be known what the people were thinking, then the second best thing is to learn about the background in which these things came from, and what led to those "gut feelings" or subconscious thoughts that brought the vampire myth into its full form.

The vampire, in fact, may have never been a popular belief, though evidence points to it being widespread across most of Eastern Europe. Because the vampire was strictly a rural, peasant phenomenon, believers would have been few in number. Evidence hints at the vampire being a gypsy notion– as most vampire tales are attributed to them– which would leave the vampire an exclusive product of a marginalized people. It is not until the West gets involved in the 1700's that the vampire gains its notoriety. Bodies were exhumed, records kept, stories written down. It is hard to tell if vampires were "discovered" often prior to written records, or if an obscure legend found root and flourished with the written word. Certainly the vampire's fame and popularity as a literary and film figure has grown since that time. It is only through putting away a modern notion of the vampire and studying sources that were will be an answer to where the vampire originated and how it flourished.

2) Ibid, 159.

3) Dudley Wright, The History of Vampires (New York: Dorset Press, 1993), 2.

4) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 2.

5) Felix Oinas, "East European Vampires," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998),47-49.

6) Katherine M. Wilson, "The History of the Word ‘Vampire,'" Journal of the History of Ideas 46: 582.

7) J. Gordon Melton, The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead (Detroit: Visible Ink Press, 1994), xxxiii.

8) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 2.

9) L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453 (New York: Rinehart & Co., Inc., 1958), 23.

10) I link the concept of the vampire with the word. Without a word for it, the concept of the vampire surely did not exist. Likewise the word did not exist without the concept.

11) L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453 (New York: Rinehart & Co., Inc., 1958), 24.

12) Ibid, 27.

13) Ibid, 41.

14) Even though the map shows the Balkans conquered in 1480, the Turks were on the move well before then.

15) L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453 (New York: Rinehart & Co., Inc., 1958), 80.

16) Ibid, 90.

17) Ibid, 88-89.

18) Ibid, 96.

19) Ibid, 108.

20) Ibid, 108.

21) Ibid, 134.

22) In much the same way that many people today, no matter what their faith, avoid black cats, carry a rabbit's foot, don't walk under ladders, etc.

23) Jan Perkowski, Vampires of the Slavs (Cambridge: Slavica Publishing, Inc., 1976), 23.

24) Felix Oinas, "East European Vampires," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 53.

25) Alan Dundes, "The Vampire as Bloodthirsty Revenant: A Psychoanalytic Postmortem," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 164.

26) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 37.

27) Ibid, 3.

28) Boccaccio, 1348. R. S. Bray, Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1996), 49.

29) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 8.

30) Ibid, 7.

31) Ibid, 4.

32) Dudley Wright, The History of Vampires (New York: Dorset Press, 1993), 3.

33) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 30.

34) Ibid, 30.

35) Ibid, 30-31

36) Ibid, 30.

37) Felix Oinas, "East European Vampires," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 49.

38) Alan Dundes, "The Vampire as Bloodthirsty Revenant: A Psychoanalytic Postmortem," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 168.

39) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 72.

40) Ibid, 72.

41) Ibid, 163.

42) Ibid, 124.

43) Ibid, 99.

44) Alan Dundes, "The Vampire as Bloodthirsty Revenant: A Psychoanalytic Postmortem," in The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 170.

45) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 4.

46) Ibid, 4.

47) Ibid, 4.

48) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 9.

49) Jan Perkowski, Vampires of the Slavs (Cambridge: Slavica Publishing, Inc., 1976), 217.

50) Ibid, 218-219.

51) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 68.

52) Ibid, 62

53) This does not usually include those who are outside the particular society; little honor is usually given fallen enemies, outcasts or religious outsiders.

54) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 124.

55) Ibid, 99.

56) Ibid, 99.

57) Ibid, 125.

58) Ibid, 99.

59) Ibid, 183.

60) Ibid, 13.

61) Ibid, 99.

62) Ibid, 147.

63) Iona Opie and Moira Tatem, eds., A Dictionary of Superstitions (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 400.

64) Ibid, 400.

65) Ibid, 400.

66) Ibid, 400.

67) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 90.

68) Ibid, 125.

69) Ibid, 125.

70) Ibid, 180.

71) Ibid, 180.

72) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 3.

73) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 92.

74) Ibid, 44, 190.

75) Ibid, 13.

76) Ibid, 90.

77) David Hicks and Margaret A. Gwynne, Cultural Anthropology, Second Edition (New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1996), 17.

78) L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453 (New York: Rinehart & Co., Inc., 1958), 149.

79) Ibid, 9.

80) Jan Perkowski, Vampires of the Slavs (Cambridge: Slavica Publishing, Inc., 1976), 188.

81) Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 1.

82) Anthony Masters, The Natural History of the Vampire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972), 67.

Barber, Paul. Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

Bray, R. S. Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1996.

Cohn, Norman. Europe's Inner Demons: An Enquiry Inspired by the Great Witch Hunt. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1975.

Dundes, Alan. "The Vampire as Bloodthirsty Revenant: A Psychoanalytic Postmortem." In The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Dundes, Alan, ed. The Vampire: A Casebook. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Durham, Edith. "Of Magic, Witches and Vampires in the Balkans." Man 23 (December, 1923): 189-192.

Hicks, David and Margaret A. Gwynne. Cultural Anthropology, Second Edition. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1996.

Melton, J. Gordon. The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead. Detroit: Visible Ink Press, 1994.

Masters, Anthony. The Natural History of the Vampire. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972.

Perkowski, Jan. Vampires of the Slavs. Cambridge: Slavica Publishing, Inc., 1976.

Mercatante, Anthony S. Good and Evil in Myth and Legend. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1978.

Oinas, Felix. "East European Vampires." In The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. Alan Dundes. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Opie, Iona and Moira Tatem, eds. A Dictionary of Superstitions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Perkowski, Jan. The Darkling: A Treatise on Slavic Vampirism. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers, 1989.

Senn, Harry. Were-wolf and Vampire in Romania. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Stavrianos, L.S. The Balkans Since 1453. New York: Rinehart & Co., Inc., 1958.

Summers, Montague. The Vampire: His Kith and Kin. New York: University Books, 1960.

Wilson, Katherine M. "The History of the Word ‘Vampire.'" Journal of the History of Ideas 46: 577-583.

Wright, Dudley, The History of Vampires. New York: Dorset Press, 1993.

This essay is 32 printed pages (more or less).

When I was writing my thesis, my advisor asked me how widespread the belief in vampires was; who all believed in it; did they actually believe in vampires. I couldn't give him an answer because no one, it seems, has ever asked that question. Did people in the middle ages believe in vampires? While surfing the internet I came across a really good site on urban legends (see link above) and some of the red flags for identifying urban legends sounded familiar. It was then that I started thinking about vampires in terms of an urban legend. I think it is quite possible that the vampire myth was, in fact, an urban (or would that be rural?) legend. So having made that rather bold statement, let's take a look at vampire legend as just that– a legend.

An Urban Legend is usually a (good / captivating / titillating / engrossing / incredible / worrying) story that has had a wide audience, is circulated spontaneously, has been told in several forms, and which many have chosen to believe (whether actively or passively) despite the lack of actual evidence to substantiate the story.1

Vampire stories (see Step 6 for some) are captivating, etc. So much so, that the ones I have retold on my site are stories that I read as a child in a book of horror/ monster stories. Even today, these vampire stories are interesting. The only difference– and a very important one at that– is that we consider these vampire stories as mere fiction. In the middle ages, the supernatural aspects of the vampire were not so improbable. The Church (whether Catholic or Orthodox) taught that the Devil was a very real creature, that could come to Earth, and could manipulate things as he chose. Witches and demons could do any number of incredible things that ordinary people could not. Though we would rank stories of demons and witches as fiction, right along with vampire stories, in the middle ages the supernatural was natural– for certain people/ things.

Vampire legend certainly had a wide audience. What we would recognize as vampire legend was spread across all of Eastern Europe– including Russia and former Russian states– and the countries of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and even parts of Muslim Turkey. (See my map) After 1730, the belief escaped Eastern Europe and spread like wildfire into all of Western Europe and even into America, before finally dying out by the 1760's in most places and certainly by the 1800's in all but the most remote sections of Eastern Europe. It is this last fact– that the belief jumped out of Eastern Europe and went into Western Europe– that most points towards an urban legend. 1730 is a significant date in history, believe it or not. It is at this time that the Ottoman Empire– which controls most of Eastern Europe and the Balkans– is being driven out by the Hapsburg (Austrian) Empire. The Hapsburg army represents the first large group of Westerners to enter the East in centuries– and possibly not since the split of the Roman Empire. So why is that significant, you ask? Well the traffic flow was not one way into the East. Those soldiers who went into Eastern Europe also came back out of it. And when they did come back home, they came back with tales of the living dead and plagues that killed off whole villages and attacks in the form of sex and blood drinking. So it is very significant that the explosion in vampire beliefs comes at the exact same time that people are traveling between an area that had the myth and one which did not.

Vampire myth also conforms to the urban legend in that it has several forms. In fact, vampire legends have so many different forms that they are often contradictory. One look at vampire legends (See Step 2) will show you two dozen different ways to find a vampire and a dozen more ways to kill it. Even the goal of a vampire is not certain: sometimes he kills at random with disease, at other times he personally attacks specific people, namely family members, whom he seems to have a vendetta against, and sometimes vampires come back home and actually turn out to be nice guys, playing the role of a loving and helpful husband. Now how can you possibly rationalize that? A simple myth, one that people actually believe in-- say the story of George Washington and the cherry tree-- stays the same, no matter where it goes. In Oregon, George Washington chopped down a cherry tree and then confessed the deed to his father. In Vermont, George Washington chopped down a cherry tree and then confessed the deed to his father. No matter where you go in the U.S., schoolchildren are going to tell you the exact same story. George didn't chop down a cherry tree and confess to it in one version and chop down a cherry tree and turn it into a soap box racer in another version. However, urban legends are known for evolving to fit the situation (the situation being the time, place, and persons participating). Compare the following vampire "fact" to George's story: In the Balkan states, the vampire roams from dusk until dawn. In Poland and Russia, the vampire roams from noon until midnight. How about the offspring of vampires: 1. Children born from a union with a vampire are born without bones– they are like jelly– and die immediately. 2. Vampires only have sons. 3. Vampires may have male and female offspring. Like with urban legends, the vampire legend can be changed to fit the situation, which is why certain aspects of vampire legend can be localized and unique to each individual village, while at the same time, as a whole, be spread across most of Europe.

An Urban Legend can be based on a true story. In these circumstances, what makes the story an Urban Legend is how it's told -- i.e., being told in the first, second or third person (or, as having happened to me, to my friend or to my friend's friend) when in fact the true event took place to someone entirely unknown to the person relating the story.<1>

Until the 1730's, all vampire myth was told from a third person point of view. Even after 1730, vampire myth was something of a second-hand account. We have documents written by people– doctors and army officers primarily– who claimed to have witnessed, first-hand, exhumations and the staking of bodies believed to be vampires. Did this really happen? It is questionable. The people who wrote these stories down might have actually witnessed this vampire hunt. Or they might have simply heard tale of such an event from someone they believed to be a reliable source and they wrote it down as if they were the ones who witnessed it; it's hard to say. People in Eastern Europe were seen as unedcuated, backwards, rural peasants, so tales of this kind would fit that stereotype. A native urban legend may have been embellished by Western outsiders to illustrate the ignorance of the people who believed in it. The only thing is that when these respectable army officers and doctors told such tales, they were taken for gospel truth, much in the same way people today blindly trust the newspaper or nightly news on t.v. What is evident is there is no first-hand accounts of a vampire attack. No one has ever written down, "I was attacked last night by a vampire." Stories tell of people living after a vampire's attack (Arnold Paole survived a long time after his vampire attack), so it would, therefor, not be impossible for a victim to step forward and relate his or her tale directly. But this never seems to happen.

Robert Pollock, author of "Good Luck, Mr Gorsky," suggested that we are prone to accepting stories that do not directly contradict our personal experiences as being true because we have an underlying need to increase our understanding of the world in which we live. Where formal methods of information have been lacking in educating us about the world, we rely on informal methods, such as the oral stories we hear from others.<1>

This is quite possibly the best explanation for why the vampire myth was so wide spread and persisted for such a long time (whereas modern urban legends come and go rather quickly, as soon as someone reports them as being false). Before the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, people's understanding of the world was limited to what they could see. Things like germs and viruses, which cannot be seen, were unknown. When a plague came through, people did not link it to an unseen bacteria, poor hygiene or contaminated food or water. They tried to rationalize what was happening based on what they could observe. This is how smell came to be linked with the plague. Bad smells were thought to cause disease (though, in actuality, they were the result of disease), so it was thought that good smells would prevent disease. Thus we get: "Ring around the rosy, a pocket full of posies, achoo, achoo, we all fall down." A nursery rhyme we've all skipped to as children is actually a tale of the bubonic plague. A "ring around the rosy" refers to a pink rash that formed on the skin– a sure sign of plague. "A pocketful of posies" refers to the flowers that people carried around with them to try and ward off the disease-causing bad smells of the plague. "Achoo, achoo, we all fall down" then refers to the sickness (sneezing) and then death. People were intimately acquainted with the disease, though they didn't know its true cause. So vampires were linked with this devastating illness as a way to explain it. People could see dead bodies lying around easier than they could see a virus in a flea's bloodstream. (And yes, I did enjoy crushing your sweet memories of innocent childhood.)

It's interesting to note that often people will tell or distribute an Urban Legend as being true when they don't wholly believe it. This is best demonstrated by the large number of chain e-mails that promise wealth from companies such as Microsoft for being forwarded, or warnings about a new gang initiation ritual etc. We may recognize that the claim is unlikely, but we distribute it any way, just in case. We don't have enough information to entirely discredit the story, so we keep our bases covered. I call this the "What if it is true?" factor.<1>

It may have been that the great majority of people in the middle ages never actually– or at least fully– believed in vampires. Although the supernatural forces at work behind witches, demons, and vampires are all closely related, there is a fundamental difference between vampires and those elements controlled by the devil, such as witches and demons. Namely, the Devil himself controlled the actions of witches and demons, whereas vampires– while often driven by an evil nature– are independent of God and the Devil. It is easier to believe that the Devil could evoke the worst in people (and thus make them witches or something of the sort) than it is to believe that the dead just get up and do whatever they want. Where would they get the power from? Witches got their power from the Devil, who, in turn, ultimately gets his power from God, but vampires were once ordinary people (in the majority of cases, at any rate). It would seem that the vampire myth might have been a bit harder to swallow than tales of wicked men and women who did things contrary to Christianity. But since there was no scientific evidence at the time to discount the undead, the story was circulated– whether or not people wholly believed it or not.

Urban legends are simply the modern version of traditional folklore. In most cultures of the world, folklore has always existed alongside, or in place of, recorded history. In this tradition, the storyteller will usually add new twists and turns to a story related by another storyteller. Just as with modern legends, old folk tales often focus on the things a society found frightening. Many of the "fairy tales" we read today began life as believable stories, passed from person to person. Instead of warning against organ thieves and gang members, these tales relayed the dangers of the forest. In old Europe, the deep woods were a mysterious place to people, and there were indeed creatures that might attack you there.<1>

If the vampire myth is a cautionary tale, what is it warning against? Actually, there are a variety of different warnings among vampire folklore. In some accounts, eating an animal killed by a vampire can turn the eater into a vampire. Warning: don't eat animals that you didn't kill yourself. This is an important warning because eating the meat of animals that die from disease, or that have been dead a while can cause any number of illnesses. Vampirism was seen a curse, an earthly hellish torment, meant to be punishment– not so much punishment for the victims of the vampire, but punishment for the person turned into a vampire. The single biggest reason for people becoming vampires was sin. If you were a bad person in life, you would be forced to walk the earth as the undead. Warning: don't lead a wicked life. Another element that is common in vampire stories is that a poor woman gets married to a wealthy stranger who turns out either to be a vampire or turns into a vampire as soon as he dies. Warning: don't marry outside your village or close acquaintances; you never know what kind of person you might end up with. Illegitimate children were also likely to become vampires. Warning: don't have sex outside of marriage or you'll curse your children. (This was very true because, even if they didn't become vampires, illegitimate children were outcasts from society.) Vampires could also be created when a body was handled properly. Warning: do your social duty and respect the dead.

The list, of course, goes on further, as it seems that most anything could turn someone into a vampire. What it illustrates is that the vampire-- whether it was an urban legend or believed to be real– was often used not only to explain the otherwise unexplainable, but it was used to keep people in line with a certain social order. The vampire was not created by any person or group in particular to accomplish this, but somewhere along the way it got twisted into a form of propaganda that urged people to stay faithful to the Church and live good lives.

Conclusion

So, after comparing vampire legend from the middle ages to modern day urban legends, can it be said with certainty that the vampire story at the time was just an urban legend? No. But it cannot be refuted either. Of course, we can't refute that people actually believed there were vampires out to get them, or even that there really were vampires, so perhaps we're not any closer to getting into the heads of medieval peasants than we were to begin with. Though, if you want my opinion, I think the vampire was an urban legend. Like the story of Blood Mary (if you say her name three times while looking into a mirror, you will see her reflection in the mirror and suffer because of it), the tale of the vampire's deeds was told on long winter nights around the fire for entertainment. And though most people treated it as a story (they didn't make it a habit to go around staking dead bodies), there was something there-- a little twinge of truth-- that kept them a little afraid to completely discount the possibility of vampires, somewhere, being real (in the same way that I have had too many strange ghost encounters to take it upon myself to prove the Bloody Mary legend wrong). Having decided that, is the vampire legend any less intriguing? Certainly not-- at least it's not for me. I think this study just calls for us to give the people of rural Eastern Europe a little more credit for common sense and rationality than was previously rewarded them.

1 Urban Legends Research Centre)

There are essentially three roles of women in the vampire world. Women may be victims or vampires themselves. The third level of attachment to the vampire world (VW) is an outside attachment, and that belongs to the women who are mere observers, such as anyone who reads a vampire book and is drawn to it. Though harder to analyze, a woman's attraction to vampire movies or literature speaks something for the appeal of the vampire in this culture, which this essay series is all about.