MY PAGE FOR TENNESSEE VOLS

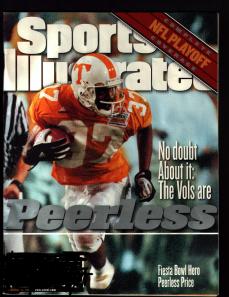

this article was taken from Sports Illustrated Jan 11, 1999 edition...

ROCKY TOP

Resilient and unselfish Tennessee completed an unbeaten season and claimed the national title by beating Florida State in a raggedly played Fiesta Bowl. By Tim Layden

THE RAGING party on the floor of Sun Devil Stadium tried to swallow Al Wilson whole, but he’d have nothing of it. He wanted only solitude. So, as his Iennessee teammates smoked fat cigars and let the repeated strains of Rocky Top wash over them after the 23-16 Fiesta Bowl defeat of Florida State that gave the Volunteers a 13-0 season and their first national championship in 47 years, Wilson, the senior All-America linebacker and locker room preacher who was the soul of the Vols, ran into a tunnel and then walked briskly toward the Tennessee locker room. “I just knew, I just believed:’ said Wilson. “So many times we needed to make something special happen, and we always did. Always.” He bowed his head and tears fell at his feet.

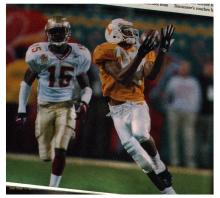

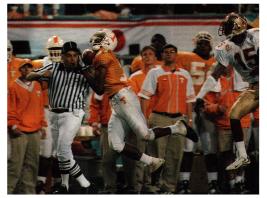

Sometimes a national title is an unblemished work of art, a portrait of irresistible class. Other times it’s a patchwork of courage and opportunism that’s somehow stitched together, big play by big play, into perfection. The last of Tennessee’s big plays came with slightly more than nine minutes left in a grinding game of field position, punts, amateurish miscues, costly penalties and seven turnovers. With the Vols leading 14-9, junior quarterback Tee Martin threw a fluttery spiral toward senior wideout Peerless Price. On the sideline Wilson watched the ball descend as if it were dropped down a chimney. “I knew Peerless would catch it,” Wilson said. He just knew. The play was called 69 All Go, meaning that three wideouts ran straight down the field. “Their defensive backs had been having trouble jamming us all night,” Tennessee flanker Jeremaine Copeland, one of those who ran deep, said after the game. As the pass fell, Florida State cornerback Mario Edwards leaped and missed. Price caught the ball and ran joyfully into Volunteers history. It was a perfect throw by a quarterback who came to Tennessee from a horrible Mobile slum and had the unenviable task of following in the footsteps of folk hero Peyton Manning.

“It wasn’t pretty early this year for Tee:’ said Manning after the Fiesta Bowl, which he attended with girlfriend Ashley Thompson. “He kept plugging and plugging. He’s gotten confidence?’ The two quarterbacks, as different in background as could be (one from privilege, the other from poverty), remain close. “We roomed together on the road:’ said Manning. “A couple of times he got phone calls telling him that friends had been killed. I’m thinking, Jimmy, this is unbelievable, but Tee is such a strong person, mentally and spiritually?’

Late Monday night Martin walked the length of the field from Tennessee’s locker room toward the team bus. After spoon feeding him offense for much of the year, Tennessee’s coaches had dumped the en tire playbook on his shoulders for the Fiesta Bowl, and he threw for 278 yards and two touchdowns. “I told Peerless I’m going to miss him next year;’ said Martin, wearing just a T-shirt in the chill desert night. He’d worn a white wristband on his left wrist during the game, on which he had written MOB, for Mobile. “Death was a part of my life in Mobile. I lost 12 friends, and there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about them. This one was for Mobile:’

Tennessee’s championship rewarded a team steeped in the workaday precepts of selfless play and glamourless labor. The Volunteers had conceived a No Stars theme last winter that carried over to their practices in Arizona last week, when they broke their offensive huddles with the chant ‘One, two, three.., underdogs!” This was in dramatic contrast to the Tennessee teams of the recent past, which stocked NFL rosters like a farm club but couldn’t ride their star power to victory over Florida, much less to a national title game. Five players from the 1997 team were taken in the first three rounds of the NFL draft, including Manning, who, despite a sensational college career, became the poster boy for greatness falling short.

This year’s Volunteers were talented too, but, in the subtle way that often distinguishes a championship team, that talent was blended like batter until it was difficult to tell the excellent players from the merely good ones and the good ones from the merely mediocre. Wilson took control of the team by launching into a tirade at halftime of the 1997 SEC championship game, an episode that endured through ‘98 for the Volunteers who witnessed it. Tennessee’s best running back, Jamal Lewis, a gifted player with a Heisman candidacy in his future, was lost for the season with a knee injury four games into the season and replaced by sophomores Travis Stephens and Trains Henry, whose nickname is Cheese because of his resemblance to a block of same.

You could trace a map of the Volunteers’ gritty path to the national championship on the face and body of 295-pound junior center Spencer Riley. A footlong purple surgical scar on the outside of his right arm came courtesy of an operation needed to repair the torn triceps he suffered in the first quarter of Tennessee’s embarrassing 42-17 loss to Nebraska in last year’s Orange Bowl. That victory propelled the Cornhuskers to a piece of the national title and the Volunteers, humbled and bullied, to the weight room. “We got beat up, period;’ says Price. Riley underwent a difficult six-month rehab, of which he remembers, “It’s not easy to wipe your butt with your left hand? That’s not a pretty image or a polite metaphor, but the Vols’ final step into the ranks of champions was similarly challenging.

Sprouting from Riley’s chin is a gawdawful, scraggly beard, a ZZ Top affectation that he began growing in mid-October and vowed not to shave off until Tennessee lost a game or won the national title. Riley’s whiskers were an apt symbol for a season in which the Volunteers won three crucial games in grungy fashion. In its season opener Tennessee was assisted by a questionable late-game pass interference call on fourth-and-seven in beating Syracuse 34-33. Two weeks later Florida lost four fumbles and missed a short field goal in overtime in a 20-17 Vols win. On Nov. 14 Arkansas quarterback Clint Stoerner fumbled with 1:43 to go to give Tennessee the last-gasp possession it needed to pull out a 28-24 victory. The cumulative effect of these escapes was to make the Volunteers feel that they were destined and to make others feel that Tennessee was lucky.

The cumulative effect of the Vols’ three narrow

victories was to make them feel destined.

In Arizona the Vols embraced the former belief more passionately than ever and used the latter as motivation. “We’d rather earn respect than have people give it to us" Riley said before the game. The Volunteers spent most of their free time secluded in their Scottsdale hotel, venturing out only for meals and the occasional trip to a virtual-reality parlor. “Miami last year, now that was a fast town;’ said junior defensive tackle Darwin Walker. “This ain’t Miami, and we’re a different team?’ Price took pride in saying that he was in bed by 10:30 on New Year’s Eve. (The once infamously raucous Seminoles were even duller; they voted to skip Tempe’s rollicking New Year’s Eve Block Party;)

Tennessee coach Philip Fulmer was quietest of all that night. He and his wife of 17 years, Vicky, declined party invitations and ate a late dinner with another couple at a Scottsdale restaurant. These are heady times for the 48-year-old Fulmer. It’s at last becoming widely known that his winning percentage of .857(66-11, excluding bowl games) is best among active coaches. Coach of the year awards have been piling up in his office like phone messages. Tennessee has signed him to a new contract worth more than $1 million per year through 2004. There are fresh signs that his program’s top-level success will have legs. Coveted New Jersey high school quarterback Chris Simms, Phil’s son, has said he will sign with the Vols. Yet Fulmer has struggled to embrace his varied riches. “I’m not very good with personal satisfaction,” he said before the Fiesta Bowl. “I’m trying, but I’m not naturally good with it.”

In turning Tennessee into a champion, Fulmer had an invaluable asset: the six-foot, 238-pound Wilson, who seemed to scare his teammates into succeeding. He rose from his seat during halftime of that 1997 SEC title game and berated the most celebrated of his teammates, calling for Manning and All-America middle linebacker Leonard Little to step up their play. He threw chairs and wept openly. “It was an incredible moment,” recalled Manning last week. “It’s hard to be a vocal leader in college. It gets embarrassing to stand up and speak. I’m a huge fan of Al Wilson’s. He’s got talent, and he’s got a look in his eyes. We need him on the Colts right now.”

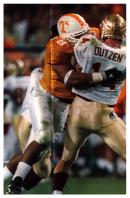

DEFENSE!!!!

DEFENSE!!!!

Wilson, who made nine tackles on Monday, came to the Vols as a big-time recruit from Jackson, Term. Tennessee was doubly lucky: Wilson nearly went to Notre Dame, and he nearly chose to pursue boxing instead of football. Working under trainer Rayford Collins at the Jackson Boxing Club from age 11 to 14, Wilson showed uncommon gifts in the ring. “He could see punches coming,” says Collins. “Incredible peripheral vision. You see it on the football field, too? He quit boxing when an older club member died in the ring of a head injury. “Al could have been a very good fighter,” says Collins.

After three good years at outside linebacker, Wilson moved to the middle for his senior season. “He’s been as good as or better than Leonard [Little] was,” said Vols defensive coordinator John Chavis last week. Wilson was the reason a solid but not dominating Tennessee defense never folded. On Monday night junior cornerback Dwayne Goodrich intercepted a pass and returned it 54 yards for a second-quarter touchdown. Even in the four games Wilson missed with shoulder and groin injuries, he was seen-and heard-every day. “He’s got this high-pitched, loud voice, and it goes right through your ears,” says sophomore safety Deon Grant.

The voice is a memory now, the soundtrack to the Vols’ highlight film.

IN A narrow stadium hallway near the Tennessee locker room, Fulmer stood among his gathered family members. His was not an easy pull to the top. A former Vols’ offensive lineman (1969-71), Fulmer replaced Johnny Majors after the 1992 season, only to have Majors and some prominent boosters accuse him of causing Majors’s downfall. Fulmer was guarded and suspicious for years thereafter. “There was an awful lot of ‘Who is this guy?’ going on,” he said before the Fiesta Bowl. “I felt I had to prove myself every day, and I was careful about what I said.” He worked long hours and watched his back.

Much changed this season. Vicky and Philip talked about their relationship, about how it works best when they spend lots of time together and about how Phillip used to take their three daughters, Courtney, Brittany and Allison, out for pancakes on Friday mornings when they were younger and how the girls, aged 12 to 15, are getting old so fast. “Philip started to say no to things that weren’t necessary,” said Vicky. He loosened up. It was a delicious by-product that his team benefited from his more relaxed demeanor. The Vols played looser. They beat Florida. Won the SEC. Won the national title.

On Monday afternoon Fulmer told his players a story that reflected his newfound approach. “The vice president [Tennessee native Al Gore] is going to be there tonight,” he said. “The governor is going to be there tonight But never mind all that. I got a call today from Ace Clement [a member of Tennssee’s National championship women’s basketball team], and she told me to tell you guys that the Lady Vols are behind you." There was laughter. Tension was broken.

In the final seconds on Monday night, Fulmer’s head filled with memories. He thought of his father, James, who worked two jobs his entire adult life and died in 1989, and of his 73-year-old mother, Nan, who still lives in Winchester, Tenn. “So many people help you get here" said Fulmer. The air was thick with cigar smoke. A championship trophy sat nearby on an orange storage crate. Fulmer wrapped both arms around Vicky and held her as though the night would never end.