JETFOIL

TESTING PROGRAM (BOEING MODEL 929)

From July 1974

to February 1975, JETFOIL 001 underwent an extensive testing program to verify,

evaluate and improve performance and to obtain vehicle class certification.

The ship was

initially configured in a "Lead Ship" test arrangement. With the

exception of the ACS (Automatic Control System), all basic ship systems were in

a production configuration. The production ACS was installed about half way

through the testing program. The passenger interiors were not installed,

although the seats were available and used occasionally to accommodate

observers, special test support personnel and to permit demonstrations to be

carried out. A ballast barrel system, borrowed from Flight Test, was used to

control weight and balance and to simulate passenger-loading conditions. The

craft configuration was rigidly controlled throughout the testing program.

A data system

provided for 150 measurements, 60 channels of FM and 90 of PCM. Real time

monitoring of 16 selectable channels was available at all times. A secondary

data system was also installed for use in "special" performance

tests. It provided 30 additional channels of which 16 could be displayed in

real time. This permitted us to double our on the spot monitoring capability

when doing exploratory or diagnostic type testing.

Initial Tests

The initial

scope of tests carried out in a new hydrofoil are intended to determine how the

vehicle behaves relative to its design objectives and to establish when it is

ready to proceed with the more critical testing phases of rough water trials,

certification trials and customer demonstrations and builders trials. These

tests are carried out in relatively ca]m water and light winds and the entire

envelopes of performance and behavior are expanded in a gradual manner in the

same way that an airplane program is carried forward. The first few days are

spent evaluating hullborne handling characteristics - the taxi tests. Since the

thrust vectoring system on the 929 was a new design, extra time was allowed for

familiarization and evaluation. Hullborne maneuverability was good to excellent

depending on the position of the foils. Maximum control was achieved with the

aft struts up and the forward strut down with strut steering engaged.

Following

the hullborne tests, speed was gradually increased to accomplish first takeoff

and straight away flight. At this time, the first performance anomaly showed up

when it became apparent that the thrust available was insufficient to achieve

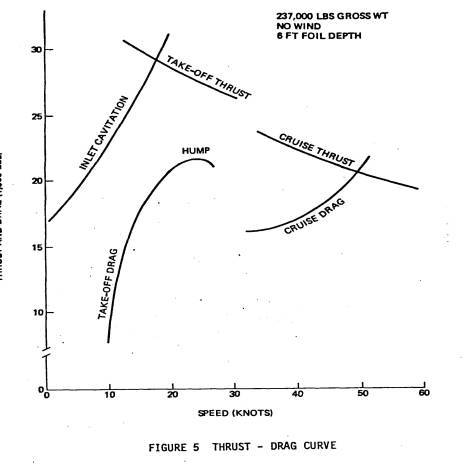

takeoff. The design thrust-drag curve for the 929 is presented below.

The

curve demonstrates the classical "hump drag" associated with high

speed marine vehicles. This arises because hull drag increases as the cube of

the velocity while foil drag increases as the square. As lift develops on the

foils, the hull drag builds up rapidly. When the hull finally breaks free, the

drag drops and then follows the square law as does an airplane wing. The

takeoff problem is one of setting the "hump drag" in a proper relationship

with the peak of the thrust curve to obtain maximum acceleration force to

get through the hump region. This can be affected by: the propulsion system,

the takeoff controller program and the incidence setting of the foils. As a

result of past hydrofoil work, it was anticipated that such a situation might

occur. A modification was made to the waterjet exit nozzles and takeoff was

successfully accomplished. Subsequent tests resulted in changes to both the

takeoff control program and to the foil incidence angle setting, which

permitted the original nozzles to be reinstalled.

Initial calm water

tests continued through August in order to fully characterize takeoff

performance, low speed trim and turning, low speed control dynamics and medium

speed trim and maneuvering. Specific tests were run to verify various automatic

control aspects including the takeoff controller, dynamic responses to step

inputs, responses to sinusoidal inputs, behavior in low and high speed turns

and high rate turns, shallow foil depth operations and simulated failures. Ship

performance throughout this entire series was very close to predicted with two

notable exceptions. The maximum speed attained was 43 knots, which was below

the expected maximum speed. During shallow depth turning tests and during

simulated broaching tests, turbine shut downs occurred. These were caused by

the inlet un-wetting which in turn un-loaded the free turbine. A protective

over-speed shutdown device in the engine automatically shut down the turbine

when this condition occurred. It was apparent that both of these situations

required additional testing in order to diagnose what was actually happening

and to develop suitable fixes.

Engineering Trials

Although special tests to develop engineering data were run

during the entire program the period from the end of August until mid-December

was devoted almost exclusively to this effort. In all, 144 trials were run

during this period for this purpose. Sixty-two were devoted to propulsion

system testing in order to try to determine whether the inability to achieve

expected maximum speeds was due to a thrust deficiency or to an excess of drag.

In all, three different size nozzles, four different inlet designs and three

different pump stators were evaluated, providing 12 basic combinations of real

interest. At the same time, twenty-eight trials were carried out to evaluate

the hydrodynamics, particularly drag. Tests were conducted at various foil

incidence angles to determine optimum settings. Flutter tests were run and

various fairing and pod revisions were made to assess their contribution to

drag. A series of drogue tests and engine shut down tests were also run in an

attempt to positively identify whether thrust was low or drag was high, with

the results indicating low thrust to be the difficulty. By December, it had

been possible to reduce the required power by 26% to produce the same speed or

conversely to increase speed between four and five knots with the major

contributions coming from a stator change (10%) and the incidence change (9%}.

Forty trials were run for foilborne control testing, twenty

on the test ACS and twenty more when the production ACS was installed. These

tests were aimed at optimizing the takeoff controller, closing the lateral

acceleration to rudder stability loop at design gain, fully evaluating

directional stability both open and closed loop and with and without the tip

fins and to eliminate any height and speed transients during turns. In

addition, a series of simulated failures were run to establish that the

resulting craft motions were not hazardous to the passengers.

Fourteen trials were run to acquire data on the various

subsystems, particularly steering and reversing, fuel, engine space cooling,

lubrication and sea water. During these tests, both interior and external

acoustic tests were also run to verify that the design levels had been met.

Rough Water Tests

The period from mid-December to the end of Ship 001 testing on

1 February 1975, was primarily devoted to rough water testing and to

certification trials. Generally, the seastate trials conditions were Seastate 4

(significant wave heights to eight feet); however, testing was also

accomplished in large swell type seas {equivalent to Seastate 5) with measured

waves to 24 feet high encountered.

Normally the JETFOIL platforms the waves, that is, the ACS

attempts to keep the deck as level as possible at a pre-selected height above

the mean surface of the sea. For seas with significant wave heights of eight to

ten feet -- or about equal to the effective strut length -- the resulting

vertical accelerations were within predicted values and the ride quality is

excellent on all headings to the seaway. Pitch and roll motions are quite safe.

As the waves increase in size, hull cresting through the

tops of the waves becomes a normal occurrence. The hull shape was designed to

keep the resulting forces and accelerations to a minimum when this happens. In

very large waves, on some headings, it is possible for the forward foil to come

near the surface, or to completely fly out of the water. This is called

"foil broaching". On other occasions, the water inlet would come to

the surface and produce the turbine shutdown situation discussed earlier. Two

modifications were developed which have been effective in solving this problem.

A "contouring" mode of control was provided which would reduce both

foil and inlet broaching, but at some degradation in ride quality. To further

protect the engines from shutdown, a pressure sensing system was installed at

the inlet, which automatically throttles the turbines back when the water

pressure drops. By combining contouring with the sensing system and using good

handling techniques, the shutdowns have been eliminated in all but extreme sea

operations.

Directional stability in all seas and for all conditions

tested was excellent. Lateral accelerations are low and were as predicted.

Maneuverability was good with full rate turns possible in all seas. Hullborne

operations, takeoffs and normal and rapid landings were made on all major

headings bm the seas and craft performance was quite good.

Certification Trials

Certification testing consists of both dockside and underway

tests and must be run on every vehicle to verify that it can be operated in a

safe manner. Generally this involves simulating electrical failures, hydraulic

failures and power failures - but the 929, being an automatically controlled

hydrofoil, presented a new problem for the agencies. To fully prove out the

vehicle, a new approach was developed.

A complete safety analysis was carried out in which all possible

failures were simulated and the resulting craft motions and forces on

passengers, crew or structure were predicted. The agencies then reviewed the

analysis and selected those failures that they wished to have demonstrated

(Table I). In addition to the usual ones, they also selected those that

produced the largest motions and/or forces (*). Since it was impossible to

simulate the latter without a considerable amount of special equipment, it was

agreed that they would only need to be demonstrated on 001. The test results

showed that the ship responses and the forces .were more benign than had been

predicted by the analysis and they fully substantiated the structural integrity

and safety of the design.

|

REGULATORY AGENCY

SIMULATED FAILURE TRIALS FOILBORNE - RATED

POWER - STRAIGHT RUNNING FORWARD

FLAPS FULL UP AND FULL DOWN * FORWARD

STRUT HARD OVER * AFT

OUTBOARD FLAP FULL DOWN * AFT

INBOARD FLAP FULL DOWN * SINGLE

HYDRAULIC SYSTEM FAILURE SINGLE

AND DUAL HEIGHT SENSOR FAILURES GYRO

SYNCHRO FAILURE * ACS

PRIMARY POWER FAILURE ACS

TOTAL POWER FAILURE FOILBORNE - RATED

POWER - MAX. RATE TURN AFT

OUTBOARD FLAP FULL UP * FORWARD

FLAPS FULL DOWN * HULLBORNE - NORMAL

RUNNING SINGLE ENGINE OPERATION SINGLE HYDRAULIC SYSTEM OPERATION TABLE I |

002 and 003 Tests

By December, 002 had entered into test. It was a slightly different configuration with the main performance difference being

that it had much shorter struts than 001. In 25 testing days, 002 accumulated

62 flight hours and in the process completed builders trials and certification

trials. The owner, Far East Hydrofoil Company, Ltd., accepted the ship in

February and as the "Madeira" it entered scheduled service between

Hong Kong and Macao in April, 1975.

003 began testing in March and completed 101 flight hours in 28 test

days. The main highlights of its program was the completion of all U. S. Coast

Guard certification testing and the completion of acceptance tests for the

customer, Pacific Sea Transportation Company, Ltd. of Hawaii. 003, christened "Kamehameha",

began inter island service in Hawaii in June, 1975.

SUMMARY

The testing program carried out on the Boeing 929 was the most extensive

test program ever run on a hydrofoil. From a testers point of view, it was very

successful. It demonstrated what the 929 could do, what its limitations were

and where improvements had to be made. It provided the information that was

needed to train the operating crews and maintenance personnel.

From first flight to introduction of the first Jetfoil into scheduled service

took ten months. It is interesting to note that the average time from first

flight to first service for the 707, 720, 727, 737 and 747 was also ten months.

.