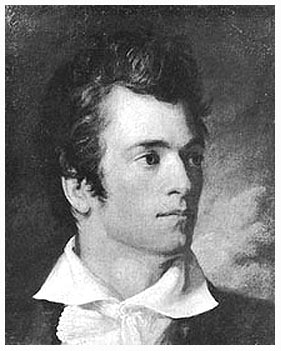

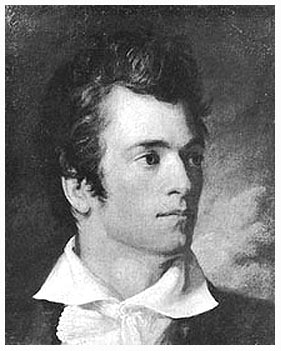

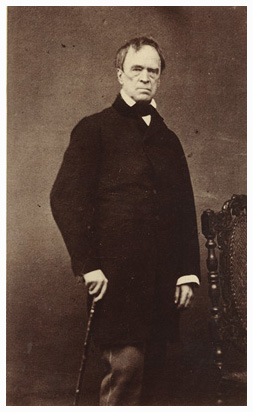

Self-portrait as a young man

Update, September 28, 2006: Catlin and Schoolcraft

Update, November 5, 2010: Catlin's lament

Self-portrait as a young man

Update, September 28, 2006: Catlin and Schoolcraft

Update, November 5, 2010: Catlin's lament

Of the thousands and millions, therefore, of these poor fellows who are dead, and whom

we have thrown into their graves, there is nothing that I could now say that would do them

any good [...] while there is a debt we are owing to those of them who are yet living, which

I think justly demands our attention, and all our sympathies at this moment.

- George Catlin

Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions

of North American Indians, Dover Publications, New York, 1973.

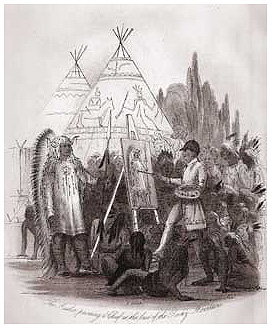

George Catlin’s opus magnum, both richly painted and poetically written, including a collection of artifacts gathered over a lifetime, is not only worthy of any anthropolgist, but illustrates also that Art is the matrix of all the sciences. Like Goethe, Catlin's interest was multi-faceted, and his writings display astute statements concerning such diverse disciplines as minerology, geology, botany, zoology, linguistics and two that didn't exist in his day: anthropology and psychology. And all of these were tied together with what Goethe called "the knot that no one sees" – Art.

Catlin's overview of aboriginal North and South America encompasses the widest possible panorama of the mystery, and although a sketch offers another mode of investigation than the compartmentalized mode of science. The keenness of Catlin's perception in this regard can be illustrated by this observation made at the end of his life in Last Rambles: I once spoke to a curator at Stockholm’s ethnographic museum about Native California, and he rudely interrupted me, saying that my manner of expression "lacks structure." That it lacks scientific structure, I do not deny. But the artistic structure behind my words escaped the anthropologist, despite the fact that the art of a given culture is uppermost in the study of anthropology! In the same respect, the artistic structure in Catlin’s writings on Native America escapes the anthropologists, who give the man and his opus less respect than they deserve. Catlin committed errors. Anthropologists commit errors. Why should Catlin’s errors deny him legitimacy in the eyes of the scientists, when their own errors are forgiven?

In an essay published in 1887 entitled "The Structure of Geography," Franz Boas wrote: "Cosmography is closely related to the arts, as the way in which the mind is affected by phenomena forms an important branch of the study. It therefore requires a different treatment from that of the physical sciences." The "different treatment" of the artistic phenomena studied by anthropologists – a spiritual treatment – is not yet in practice. It was however George Catlin’s normal treatment of the native cultures he studied. That which is under study in the field of cultural anthropology is culture. That element of culture which endures longest and is the most meaningful is Art. Here is where George Catlin possesses expertise in Native American cultures that no anthropologist has access to. To have this expertise, one must be an artist. This is why the medicine men whom Catlin encountered immediately recognized his "great medicine" and saw him as a colleague. The "different treatment" Boas saw as necessary for the study of culture can be seen by some scientists as "lacking structure." The structure is there, however, to more alert minds.

An historian often investigates culture in a more artistic frame of mind than do scientists. One of the major historians of North America, Bernard de Voto, clearly saw the (unpaid) debt America owes George Catlin: "So far as the plains tribes are concerned, in fact, and despite all the observations of earlier travelers among them, American ethnography may be said to begin with Catlin." (Across the Wide Missouri) And yet, certain Native American intellectuals today do not take George Catlin seriously, even though powerful chieftains, medicine men and warriors held him in awe. These modern native scholars believe that Catlin had an overly romanticized view of the "Indian" which he used to contrast with his discontented view of his own society. A closer reading of Catlin’s work, however, will reveal that he was not always filled with admiration for the indigenous peoples of the New World. For example, he felt that the vanity and homicidal pride of the warrior were worthy only of ridicule. Catlin’s "fanciful world," as one Native American intellectual put it, may be flawed with wishful thinking concerning the inherent virtue of the tribes. But his unequaled over-view of aboriginal life in North and South America is certainly not "concocted" as this intellectual believes.* The confrontation between the indigenous peoples of the Americas and the Europeans was an epic misunderstanding on both sides. This mutual misunderstanding is still the status quo today. The biggest misunderstanding on the part of the indigenous peoples was to believe that the Europeans could be trusted. For the Euro-Americans, the biggest misunderstanding was that epic genocidal crimes could be committed against these peoples without one day paying the price in full for them. In this regard, Catlin’s misunderstanding is slight, while his understanding and compassion for the indigenous peoples he met on his "rambles" is unequaled among Euro-Americans. Or, perhaps the above-mentioned native intellectual’s scorn is warranted for Catlin’s overly "romantic" view of people who were indeed equally as corrupt and depraved as the Europeans all along?

George Catlin was too honest for the society which fostered him, and therefore censored himself when thinking of all those tribes he loved that were being exterminated and where some of his friends, like the Mandan chief, Four Bears, were to die wretched deaths – deaths unworthy of dogs – inflicted by the American Dream. "To speak of these scenes without giving offense to the world" was his stated purpose in Catlin’s first book. He apologized repeatedly for asking his busy, civilized readers to slow down a tiny bit the pace of their destruction so as to "take the pains to read it" and thus learn about those whom they were in the process of exterminating, hopefully without Catlin having "trespassed too long upon their time and patience." From the first landing at Plymouth Rock to the first landing on the moon, I can think of no American of European ancestry whom I admire more.

Both the Botocudos and Payaguas [of Patagonia] wear the block of wood in the upper lip as an ornament, like the Nayas Indians of Queen Charlotte's in North America, already spoken of. How surprising this fact! that, on the northwest coast of North America and the southeast coast of South America almost the exact antipodes of each other, the same peculiar and unaccountable custom should be practiced by Indian tribes, in whose languages there are not two words resembling, and who have no knowledge of each other. Such striking facts should be preserved and not lost, as they may yet have a deserved influence in determining ultimately the migration and distribution of races.

Among those who have been negligent in their recognition of George Catlin are the anthropologists who followed in his footsteps. Franz Boas is generally acknowledged by them as "the father of American anthropology." When I once suggested to an archaeologist in Santa Barbara that George Catlin in fact deserves this title, even though he was a mere artist, I was given a look that said: "Here is an ignorant fellow." George Catlin has not found many friends among the anthropologists who have, however, greatly profited from his work. He is considered scientifically inaccurate and overly romantic. And yet his epic overview of Native North and South America came before even Franz Boas was born.

The artistic technique of the sketch precedes the more detailed elaboration that comes later. The sketch is often inaccurate and very different from the finished work. But it sends the worker off in the right direction. Scientists have very little sympathy or understanding for the artistic method of investigation which was Catlin’s.

Among those who have been negligent in their recognition of George Catlin are the anthropologists who followed in his footsteps. Franz Boas is generally acknowledged by them as "the father of American anthropology." When I once suggested to an archaeologist in Santa Barbara that George Catlin in fact deserves this title, even though he was a mere artist, I was given a look that said: "Here is an ignorant fellow." George Catlin has not found many friends among the anthropologists who have, however, greatly profited from his work. He is considered scientifically inaccurate and overly romantic. And yet his epic overview of Native North and South America came before even Franz Boas was born.

The artistic technique of the sketch precedes the more detailed elaboration that comes later. The sketch is often inaccurate and very different from the finished work. But it sends the worker off in the right direction. Scientists have very little sympathy or understanding for the artistic method of investigation which was Catlin’s.

(excerpt from Hitch-Hiker in Hades)

* David Anthony Tyeeme Clark (Me’ckwa’ki’agki), American Indian Quarterly, Spring, 2000.

x

x

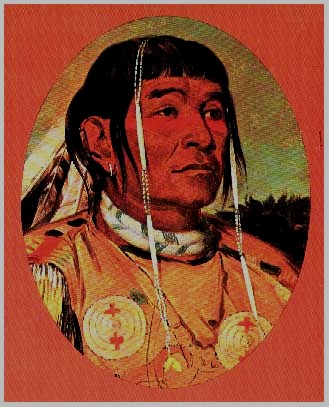

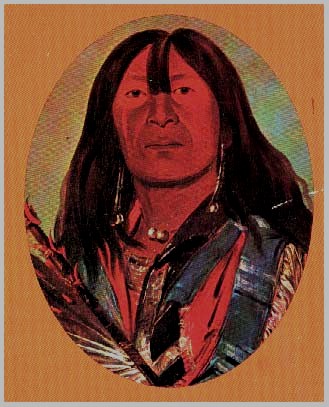

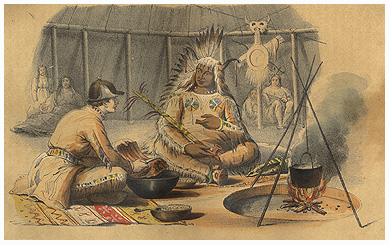

(left) Sha-co-pay (The Six), chief of the Ojibway. (right) Shon-ka (The Dog) Lakota

(covers to vols. I and II of the 1973 Dover edition of Letters and Notes...)

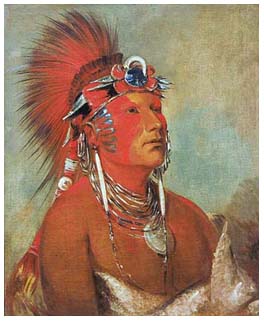

The idiotic male pride of the Lakota warriors Shon-ka (The Dog, above right) and Mah-to-che-ga (Little Bear, left), both of whose portraits George Catlin painted, led to both of their violent deaths, warfare between their two bands, and a death sentence on Catlin. After having painted many portraits of warriors from full-face (including that of Shon-ka), Catlin decided to paint Mah-to-che-ga in a partial profile, as is an artist's prerogative. Shon-ka, who was "an ill-natured and surly man – despised by the chiefs of every other band," watched Catlin paint and sneered at the sitter:

The idiotic male pride of the Lakota warriors Shon-ka (The Dog, above right) and Mah-to-che-ga (Little Bear, left), both of whose portraits George Catlin painted, led to both of their violent deaths, warfare between their two bands, and a death sentence on Catlin. After having painted many portraits of warriors from full-face (including that of Shon-ka), Catlin decided to paint Mah-to-che-ga in a partial profile, as is an artist's prerogative. Shon-ka, who was "an ill-natured and surly man – despised by the chiefs of every other band," watched Catlin paint and sneered at the sitter:

- Mah-to-shee-ga is but half a man!

He taunted his tribesman, saying that Catlin had painted only one half of his face because the other half was good for nothing. Moments after the portrait was finished, these two had a shoot out and Little Bear was killed by The Dog, the side of his face deemed "good for nothing" very strangely shot away. The two bands became enemies, although of the same tribe. The Dog and his brother were killed by Little Bear's people and this bit of lunacy was immortalized in Catlin's notebooks and the last portrait Catlin did among the Lakota. (excerpt from Hitch-Hiker in Hades)

Amazon lagoon

George Catlin

"In the fresh air and sunshine at the tops of the trees, which we never can see,

there is a busy and chattering neighbourhood of parrots and monkeys,

but all below is a dark and silent matted solitude, in which a falling leaf,

for want of wind, may be a month reaching the ground, and where a man

may be tracked by the broken cobwebs he leaves behind him."

(George Catlin, "An Amazon Forest", Last Rambles, chap. II)

Catlin’s “last rambles” were an epic voyage that took him to Amazonia, Patagonia, and then up the entire length of the Pacific coasts of South, Central and North America to British Columbia, and even further to the Bering Strait and Siberia, painting the tribes and taking notes all the way. (When he needed an easel, his dark companion Caesar’s back served the purpose.) He was no longer the young and vigorous man who had made that astounding pilgrimage among the North American tribes, hauling his art supplies into the most inaccessible regions of the continent (as he did nonetheless as an old man in South America). Being a follower of the Way, Catlin could see genuine human nature when he left civilization to visit the last native cultures that he knew would soon go extinct: "What gleaming, laughing, happy faces! Oh, that human nature refined were half as happy, and sinned as little!" (Life Among the Indians)

Staid in doors all day talking & looking at Geo's works. Dinner at 4. Talked & laughed at his constant jokes and wit. [...] There is an old woman directly under our window who sells hard-boiled eggs & hot boiled potatoes. Geo sends a handkerchief down on a line with 2 cents & hauls up 1 doz. potatoes and salt. – Eats them almost every night – when he can't get Baked Apple Pistolets.(Brussels, November 15, 1868)

Catlin had four more years to live. After thirty-two years absence from his homeland, the valiant old man stood on the ship's deck and blissfully watched as he approached the shore of New York – like Odysseus returning to Ithaca with his treasure. Catlin's biographer and kinswoman, Marjorie Catlin Roehm, wrote: "The artist had touched the stars, and groped for a foothold in the pit of despair." Still, still he continued calmly into his desperation and neglect. Alas, his countrymen had no healthy welcome to give the great man. His one last wish was to find a safe resting place for his treasure, like Odysseus' cave. What would become of his Indian Gallery? Already many paintings had been damaged and some destroyed because, seen as worthless, they were stored in a sooty factory for decades. (Such barbarity is only matched by the Prussian soldiers who butchered beef on Monet's canvases.)

Catlin had four more years to live. After thirty-two years absence from his homeland, the valiant old man stood on the ship's deck and blissfully watched as he approached the shore of New York – like Odysseus returning to Ithaca with his treasure. Catlin's biographer and kinswoman, Marjorie Catlin Roehm, wrote: "The artist had touched the stars, and groped for a foothold in the pit of despair." Still, still he continued calmly into his desperation and neglect. Alas, his countrymen had no healthy welcome to give the great man. His one last wish was to find a safe resting place for his treasure, like Odysseus' cave. What would become of his Indian Gallery? Already many paintings had been damaged and some destroyed because, seen as worthless, they were stored in a sooty factory for decades. (Such barbarity is only matched by the Prussian soldiers who butchered beef on Monet's canvases.)

This splendid good will to the continent of Turtle Island no president nor congress has ever matched. An artistic gift had kept Catlin healthy and unharmed, even after many decades of perilous travel. Now he paced a room in his daughter's house in New Jersey in his seventy-sixth year. His sorrows were many. His wife Clara and his infant son George died suddenly in London. From the world-wide fame and success that his Indian Gallery had given him as a young man, he found himself stripped of everything like Job. His three beloved little girls were legally taken from him (for in truth, he could not provide for them), leaving him alone and destitute as an old man. And yet, as Francis wrote, he was still filled with jokes and laughter. He tried to walk off his final weakness in the house in Jersey City, until his strength gave out. "Oh, if I was down in the valley of the Amazon I could walk off this weakness."

Little was left undone in this astonishing life. He was only concerned about the fate of his paintings. Almost the last words Catlin uttered were: "What will become of my Gallery?" He was buried in Brooklyn, beside his wife and son in an unmarked grave. It did not receive a headstone until nearly ninety years after his death, not from the government which had so fiendishly ignored this American master, but from a private group of friends and descendants of George Catlin. After insulting decades of trying to interest the government in his Indian Gallery, he did not succeed. The government now owns his Indian Gallery, but did not acquire it through even the faintest gesture of good will to the artist. (Excerpt from Crazy Devil Sweeping)

Update, September 28, 2006

Catlin and Schoolcraft

Just as the artistic origins of religion are ignored by priests, the artistic origins of science are ignored by scientists today. The evidence is there, but not perceived. American museums of natural history, for example, have a scientific foundation, and yet the first American museum of natural history was artistic in nature, conceived by the patriarch painter Charles Willson Peale. The first complete skeleton of a mastadon ever dug up and put together for display was not the work of scientists, but of the artists Peale and his son Rembrandt. Before the scientific theory lie the little-known techniques of aesthetics.

Once a scientist acknowledges the artistic origins of science, he or she has no other choice but to respect the artist. But this is not possible unless the scientist overcomes academic pride. Alas, this did not occur when the official ethnologist of the United States, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, traveled to London in 1846 with the express purpose of meeting the master, George Catlin. The scientist wanted the artist's permission to use his many paintings of Native North Americans for illustrations in a statistical work on the tribes which Schoolcraft hoped to edit for the United States government.

Along with being grief-stricken over the sudden death of his wife Clara and their infant son George, Catlin was in desperate financial difficulties that would eventually lead him to a London debtor's prison. The scientist assured the artist that his paintings would help stimulate sales of the scientific work, considering Catlin's fame and expertise, thus making a fortune for the artist. Catlin had by then achieved wide-spread recognition and praise for his paintings, drawings and writings on Native North American cultures, which today are a national treasure. The refusal of the government to purchase Catlin's Indian Gallery aggravated his poverty and despair over having lost this fruit of heroic toil to his creditors, but Catlin could only refuse the scientist's less than generous proposal. The artist told the scientist that he had gone to great expense and labor to publish his own written works on the tribes illustrated with lithographs he had painstakingly copied from his paintings. Catlin instinctively knew that his artistic opus was superior to the scientific opus planned by Schoolcraft, and being associated with this deterioration in quality did not appeal to him, even with the promise of making a fortune. Refusing to honorably purchase from Catlin for a low price paintings that are now cherished as a national treasure, the government now tried to blackmail him into being swindled and sullied by Schoolcraft.

Along with being grief-stricken over the sudden death of his wife Clara and their infant son George, Catlin was in desperate financial difficulties that would eventually lead him to a London debtor's prison. The scientist assured the artist that his paintings would help stimulate sales of the scientific work, considering Catlin's fame and expertise, thus making a fortune for the artist. Catlin had by then achieved wide-spread recognition and praise for his paintings, drawings and writings on Native North American cultures, which today are a national treasure. The refusal of the government to purchase Catlin's Indian Gallery aggravated his poverty and despair over having lost this fruit of heroic toil to his creditors, but Catlin could only refuse the scientist's less than generous proposal. The artist told the scientist that he had gone to great expense and labor to publish his own written works on the tribes illustrated with lithographs he had painstakingly copied from his paintings. Catlin instinctively knew that his artistic opus was superior to the scientific opus planned by Schoolcraft, and being associated with this deterioration in quality did not appeal to him, even with the promise of making a fortune. Refusing to honorably purchase from Catlin for a low price paintings that are now cherished as a national treasure, the government now tried to blackmail him into being swindled and sullied by Schoolcraft.

xxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxx

- Byron, The Corsair

NOTE: In order to defend himself against such accusations

Catlin made a habit of documenting his portraits

with an affidavit signed by a witness that the

painting was made from life, as in the above

affidavit signed by the army officer

Captain E. A. Hitchcock.

Through his Ojibway wife Jane and her mother and sisters, Schoolcraft was given direct contact to Ojibway legends and myths. Nevertheless, he could only regard the source of these myths as "the dark cave of the Indian mind." Only by becoming "civilized" would a benign effect on these ignorant native souls be produced. The stern presbyterian Schoolcraft believed that his ideas were "ethnological truths", while George Catlin believed that we, not they, should be educated.

Not long before his death, Catlin wrote to his brother Francis concerning the claim by Schoolcraft that he was a liar: "It would be a great pity if [...] I [am] allowed to die off with such a Government libel hanging on my name and works." This official condemnation of Catlin by his own government in turn swayed the French government against buying the artist's Indian Collection. Great men of the age praised Catlin, but he remained destitute and alone in Brussels. Baudelaire was charmed by Catlin's paintings. Baron von Humboldt and Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied (who had followed Catlin's footsteps into the wilds of the Upper Missouri with the master painter Charles Bodmer), both supported Catlin, alert to his genius and historical importance.

But his own government, which now covetously guards his Indian Gallery, abandoned the deaf old man to his poverty and loneliness until his death, at age seventy-six. Who can say why an artist's countrymen are inimical to him when he is alive, and praise him as a national hero long after his death, doing him no good whatsoever? (Excerpt from Crazy Devil Sweeping)

Update November 5, 2010

Catlin's Lament

Further reading of George Catlin’s ”errant and chequered life” (Last Rambles) reveals a strange ambiguity in his belief system concerning Native America and the natural environment of the Americas. In Catlin’s Lament: Indians, Manifest Destiny, and the Ethics of Nature John Hausdoerffer introduces the reader to “Catlin’s lament”, in which this ambiguity gradually becomes manifest. On one hand, the “lament” is what I first understood it to be: full empathy for the tragedy of “vanishing“ Native American cultures and antipathy for the civilization that was systematically and with premeditation destroying them. This understanding of the “lament” can be likened to Samson’s lament for the society of the Philistines – his own society – which evoked such antipathy in him that he destroyed it along with himself. In the arms of Delilah, Samson was – in stark contradiction to his later antipathy – an advocate of her society of Philistines.

Further reading of George Catlin’s ”errant and chequered life” (Last Rambles) reveals a strange ambiguity in his belief system concerning Native America and the natural environment of the Americas. In Catlin’s Lament: Indians, Manifest Destiny, and the Ethics of Nature John Hausdoerffer introduces the reader to “Catlin’s lament”, in which this ambiguity gradually becomes manifest. On one hand, the “lament” is what I first understood it to be: full empathy for the tragedy of “vanishing“ Native American cultures and antipathy for the civilization that was systematically and with premeditation destroying them. This understanding of the “lament” can be likened to Samson’s lament for the society of the Philistines – his own society – which evoked such antipathy in him that he destroyed it along with himself. In the arms of Delilah, Samson was – in stark contradiction to his later antipathy – an advocate of her society of Philistines.

Catlin frequently contrasts “civilized“ with “savage“ in his writing, seemingly more sympathetic to the latter, which he understood to mean (as did Thoreau) “forest dweller“, derived from the latin sylvan. His lament for what he and his contemporaries saw as “vanishing“ cultures, plant and animal species, and wilderness areas was, as Hausdoerffer implies, a self-fulfilling prophecy that accompanied the destructive vision of Manifest Destiny. A lament is two-sided. I lamented the cancer that killed my mother for its rapacity, and my mother for the suffering it inflicted on her. A destiny that was gradually manifest to her loved ones decreed that the cancer would prevail. Our mother/continent is as well inflicted with cancer. Lamentations evaporate into the universe with no effect on a situation which is destined.

On the other hand, despite George Catlin's sympathies for Native America, his work embodies the same prevailing vision of Manifest Destiny as those Americans who were eager to conquer the continent and steal billions of acres from its Indigenous Nations at whatever the price. This other spin to Catlin’s lament reveals his own complicity in the destruction of Native American societies, leaving in its wake the legacy of Catlin being both their friend and their exploiter. Hausdoerffer writes how his good intentions coexist with “Catlin's ideologies of lamenting away real Indians while preserving their ghosts [paintings and artifacts].“ Prevailing social and cultural conditions in the mid-19th century United States are key to understanding what Hausdoerffer calls ”the intricacies of what Catlin both challenged and consented to.” In the 1830s 70,000 Native Americans were forcefully “removed“ west of the Mississippi by decree of president Jackson and the US Congress. Many thousands died in this “Trail of Tears“ which initiated policies of removal that would continue into the 20th century. Catlin attempted to live an ethical life in the midst of these tragedies, split between sympathy for the native peoples and fidelity to his own society. Although Catlin often wrote that Native American morality was superior to that of occidental civilization, he nonetheless advocated their conversion to Christianity and their assimilation into the “enlightened society” of America – the official policy of Jacksonian politics. “By all who know me and my views, I am known to be, as I am, an advocate of civilization.” (Notes of Eight Years’ Travels and Residence in Europe)

This is quite different from what Catlin had written elsewhere, especially Last Rambles and Life Among the Indians which deal with his travels in South America and the Canadian Northwest as an aging man. In the latter he writes of “...some of the finest races of mankind in America or in the world.” Hausdoerffer focuses on Eight Years’ Travels, in which Catlin is seen in the worst possible light, an exploiter of “Indians” like P.T.Barnum and Buffalo Bill, earning money on performing “savages” in London, Paris and Brussels, many of whom died from smallpox. This grotesque carnival was the precursor of the all-American Wild West Show which would result in the final degradation of great warriors like Sitting Bull and Black Elk. Even Catlin and his wife Clara donned “Indian” clothing, darkened their faces and pretended to be “Indians” for their gullible European audiences! But this disgraceful attitude of Catlin among the civilized “philistines” of Europe must be counter-balanced by Catlin sitting in a poetic trance in the Amazon jungle enraptured by the cries of the monkies, birds and other animals, which he likened to the chattering of city-dwellers on a London omnibus. Hausdoerffer does not focus on Last Rambles nor Life Among the Indians, which reveal Catlin’s more empathetic lament, and critique of the unchecked evils of western civilization. Short of abdicating from his own society and being adopted by a native society, Catlin had little choice in the matter, as do I or any other American who is not from an Indigenous Nation. However much empathy we may have for the Indigenous Nations, however much antipathy we may have toward our tyrannical and destructive civilization, we cannot abdicate – there is no where else to go.

London and the Amazon jungle are the contradictory antipodes of the aging Catlin. When he was emersed in the wilderness he loved, his lament tilted in its favor. Back in civilization, his lament was more like the collective European lament since the time of Columbus: it's a shame about the ”Indians”, but our lust for lebensraum requires their removal, extermination or assimilation into our society. Perhaps because of money worries plaguing him in Europe, Catlin the educator became Catlin the showman, openly displaying many of the negative traits of civilized man for which he had previously shown contempt. After an unsuccessful tour in England with a group of Ojibways in 1843, the following year Catlin’s sideshow had P.T. Barnum's Tom Thumb on stage with a group of fourteen Iowas brought to Europe by P.T. Barnum. Hausdoerffer refers to this aspect of the artist’s endeavors as “Catlin’s fetish”, hiding the whole context of Indigenous America to reveal “a mere desired part, abstracted from an undesirable whole historical relationship.” This idea of “fetish” is present in the portrait Catlin painted of the imprisoned Sac chief Black Hawk. Although one of the chief's tribesmen pleaded for Catlin to paint their shackles – paint the truth – the artist painted Blackhawk without his shackles. Later, in 1837, Catlin presented Black Hawk on stage in the eastern US. Hausdoerffer comments: ”Black Hawk was perhaps more a prisoner on Catlin's stage than in Jefferson Barracks.”

Despite my admiration, Catlin can be annoying with his patronizing prose, as in this beginning to chapter IV of Life Among the Indians: ”Now, my little readers, we are coming to scenes and events that will be more exciting...” My guess is that most of the readers of this book since it was published have been adults. To theatrically pretend to address children as if a puppeteer at a Punch and Judy show reveals poor judgement as a writer. To refer to Native Americans with their millennia-old knowledge of the continent as ”ignorant, and consequently superstitious people” also reveals poor judgement. Catlin believed that they instead should convert to the christian fairy tale, complete with the immaculate conception and virgin birth, that has plagued western civilization with sorrowful ignorance and superstition for two millennia. In this respect, Native American cultures have been in closer contact with the reality of Spirit than Christian cultures. As Vine Deloria Jr. pointed out in God is Red, the former are rooted in the realities of the continent and all its flora, fauna and geological features. The latter place little priority on the continent, but instead give the highest priority to vague scriptures derived from the continent of Asia (Palestine is in Asia Minor) in which very much falsehood is mixed with a bit of truth.

Hausdoerffer quotes a long passage from Eight Years’ Travels and emphatically declares it to be ”the most telling statement of Catlin's career.” The ”Indians” accompanying him in Europe seriously questioned the virtues of European civilization in Catlin's book. The passage in question reveals Catlin's odd strategy to integrate doubtful Native Americans into western society: they should be ”held in ignorance of the actual crime, dissipation, and poverty that belong to the enlightened world” until ”their prejudices against the white men are broken down.” That is, Native Americans should be tricked into assimilation into a society which Catlin himself saw as crime-ridden and dissipated. This reasoning is like the a young girl who is sexually molested by her step-father being persuaded by her mother that ”he is a good provider” and that she should therefore obey him. It reveals a perverse twist to Catlin's idealism that is impossible to accept.

Thus, the Euro-American who had the greatest empathy for Native Americans among 19th-century writers himself contributed to the “inevitable vanishing“ of their cultures. His epic journeys into the American wilderness were possible because of his contacts with government authorities like General William Clark, who was part of the apparatus that was destroying native cultures. The Lewis and Clark expedition made an assessment of the Louisiana Purchase for the development and opportunity of the United States at a future time. Despite the good relations that were established with most of the Indigenous Nations they encountered, the Lewis and Clark expedition was also a mission of espionage which gathered data on tribes who in the coming decades would be waging wars of self-defence against the United States.

Catlin’s view of Indigenous Americans, although ambivalent at times, is judicious, intelligent and devoid of the haughty rhetoric of the age bewailing “cruel and treacherous Indians.” Born 20 years after the American revolution he admitted what few Americans admitted at the time: cruelty was a trait prevalent on both sides. His maternal grandfather survived a massacre of over 500 white militia in Pennsylvania who had invaded native territory with the sole intent of stealing it. Catlin disagrees with the common appraisal of this successful ambush as “treachery”: “It was strategy, not treachery; and strategy is a merit in the science of all warfare.” (Further on in the book Catlin defines treachery as the often used method of Americans attacking natives who approached them under a white flag of truce, prefering to call it strategy instead.) After this victory the natives took possession of the fort along with its inhabitants, who were mostly women and children. Among them was Catlin’s grandmother and her seven-year-old daughter – Catlin’s mother.

Catlin’s Life Among the Indians begins with this story, and how his maternal grandfather, who survived the massacre by swimming across the river, was the source of many interesting stories of “Indians”. The book continues with the nine-year-old George Catlin’s first encounter with an “Indian”. Against his father’s orders the boy took the heavy rifle of his older brothers and hiked off to the “salt lick” by the “old saw mill” to wait in ambush for a deer. Although he had often fired a lighter rifle hunting rabbits, he had never fired this big gun. After a long wait, a deer came to the “lick”. The boy Catlin took aim several times, but he was too nervous and his hand was trembling so much that he hesitated pulling the trigger for fear of missing and scaring away the deer. By gritting his teeth he succeeded in getting a steady aim and then – bang! But it was not little George’s rifle that went off. He had not been alone in his ambush. The “graceful form of a huge Indian” emerged from the forest to skin and gut the deer he had just shot, as the boy watched in amazement and awe:

Who will ever imagine the thoughts that were passing through my youthful brain in these exciting moments? For here was before me, for the first time in my life, the living figure of a

Red Indian! “If he sees me I’m lost; he will scalp me and devour me, and my dear mother will never know what became of me!”

Catlin was so terrified that he froze until the hunter left with his prey. His fear was such that he fled home forgetting the rifle and his hat. A day later, the young Catlin was walking in the wheat field with his father when they encountered the same Indian that had frightened him the day before, sitting on a bear hide with his wife and ten-year-old daughter, roasting the venison. The boy and his father shook hands with the man, who was an Oneida named On-o-gong-way. “The friendly grip of his soft and delicate hand... soon dissipated all my fears, and turned my alarm to perfect admiration.” The boy and the father sat down with On-o-gong-way and smoked his pipe of friendship. Looking at the boy, he called him a “good hunter“ and going to a nearby tree where “where he had suspended a small saddle of venison,“ he cut away half the meat and gave it to Catlin, saying, “Dat you, you half.“

He told them of coming hundreds of miles over territory where white hunters shot native people on sight. Ironically, he was the son of a warrior who had participated in the massacre from which Catlin's grandfather had escaped before the artist was born. His people's disastrous retreat resulted in a reverse massacre at the hands of the whites. He pointed to the fields of Catlin's father and said that in those days it was a forest where a bloody battle had been fought with heavy losses on both sides. A sincere friendship developed between On-o-gong-way and Catlin's little community. Leaving another deer saddle as a departing gift, he vanished one day. Later, On-o-gong-way's body was found in a valley eight or ten miles from Catlin's home pierced by two rifle bullets. No one could say what happened to his wife and little daughter.

It is astonishing that school children in the US grow up reading about the fictitious characters Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, but few if any come into contact with the true stories that Catlin recounts in his books with at least as much skill as Mark Twain. Whereas “Injun Joe” was the villain in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Catlin’s first “Indian” in Life Among the Indians (which is addressed especially to children) is the hero. “Injun Joe“ is inherently evil because of his “Indian blood,“ a fact which the novel’s characters state repeatedly. He plans on torturing the widow Douglas in ways that he imagines are most excruciating for women. Mark Twain’s fictitious stereotypical “Indian“ says, “When you get revenge on a woman you don't kill her – bosh! you go for her looks. You slit her nostrils – you notch her ears, like a sow’s!“ Catlin’s real Native American however is a peaceful family man and hunter who would be the starting point of Catlin’s life-long fascination with indigenous peoples and his unequalled narrations and painted images of their “manners and customs”.