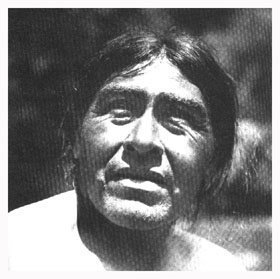

ISHI

Ishi's death mask

Ishi in Two Worlds

Theodora Kroeber

UC Press 1976

Ishi looked upon us as sophisticated children - smart, but not wise. We knew many things, and much that was false. He knew nature, which is always true. His were the qualities of character that last forever. He was kind; he had courage and self-restraint, and though all had been taken from him, there was no bitterness in his heart. His soul was that of a child, his mind that of a philosopher.

- Saxton PopeIshi was the last member of the Yahi tribe in Northern California, who wandered dazed and emaciated into Oroville in 1911. He was prepared to give himself up to those who had killed his entire tribe, prepared to be in turn killed by them. His hair was burned off in mourning and he was dressed in a ragged garment given him by his captors when he was first photographed. Bewildered by the photographer's sulphurous explosion, he appears as if stopped by hecklers on the way to Golotha Hill to be crucified. (He may even have experienced this strange new thing, the camera, as the manner by which he was to be executed.)

Ishi as captive, Oroville 1911Unable to speak any language but Yahi, he could very well have been crucified by the zealous Americans who wanted to exploit this "wild man" for all he was worth, had not blessed fate brought Thomas T. Waterman, Dr. Saxton Pope and Alfred Louis Kroeber to his aid. Kroeber was director of the newly formed San Francisco Museum of Anthropology, which was to be Ishi's home for the remaining five years of his life. It was here that Ishi was "employed" as a janitor for $25 a month, sweeping around installations, artifacts and reconstructed native huts like those in which he lived in the remote wilderness of Deer Creek.

Ishi and Alfred Louis KroeberIshi was born at the beginning of the 1860s at a time when California’s native peoples were being decimated by gold hunters and settlers. The Yana people – of which the Yahi are the southernmost branch – were at one time 1,500 individuals but quickly decreased when the discovery of gold in 1848 brought with it a tidal wave of gold-hungry fortune hunters. During his lifetime Ishi's people were massacred and persecuted and their numbers declined more and more.

Those left alive stayed hidden and moved about only at night. It was as if they had been swallowed by the earth. The local inhabitants thought that they had gone extinct. But for several decades a little group remained. They lived in ingeniously camouflaged huts. They could travel long distances hopping from stone to stone to avoid leaving footprints. Every footprint they left they covered with dead leaves. Their paths ran beneath the chaparral and they went on all fours. They broke no branches and cut no wood. They spoke softly around small fires without smoke. For a few more years the Yahi people’s stories were heard in whispering tones, and their collective memory was shared by a little group of slowly disappearing human beings.

In 1908 only Ishi, his aging mother, an old man and a young woman remained. But when mineral seekers came up into their small ravine, the old man and the young woman drowned while trying to flee. The mother was taken by the whites but died soon after. Now Ishi was totally alone. For three more years he would wander around the landscape that once was the homeland of his people. No one could speak his language anymore, nor share his memories, stories and sorrows.

The best good will of the United States as emanated through Kroeber could only install the last warrior of the Yahi nation as a living museum artifact like those he dusted in his janitor's uniform – instead of the kingly generosity shown to the shipwrecked, stranded and stark-naked Odysseus by good king Alcinous – that Ishi deserved. No one knew Ishi's name, for he was unwilling to tell anyone, even his best friends at the museum. It was a sacred name, forbidden to be divulged. Ishi means simply "man" in Yahi.

When he died of a disease caught in civilization (tuberculosis) his language and culture, which had existed for millennia, went extinct. Although Ishi died knowing that the Americans had committed an irrevocable genocide of his people and culture, there was no hatred in him as one often sees in Afro-Americans. He died sweetly with a smile, evidence that the curse of his people over the heads of their executioners was potent:

Suwa! Se' galt! Maya! For unexplainable reasons, Ishi was not allowed a final sacred rest by the anthropologists - even in death. Does it matter that this ghoulishness excuses itself because it is carried out "in the name of science"? At his death in 1916, Ishi's brain was removed and sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. The scientific information thus obtained (whatever that may have been) was regarded as more important than the most rudimentary respect granted the dead all over the world. Anthropologist Orin Starn's research eventually led him to the Smithsonian's Natural History Museum where he beheld Ishi's brain: "Ishi's brain was right there in Tank 6 of the Wet Collection...There were thirty-two other brains floating in the stainless steel tank, each in a cheesecloth sack tied with a plastic accession tag." (American Indian Quarterly Summer/Fall 2005) It took almost one hundred years for Ishi's remains to be released by the scientists for a proper burial by Native Californians. This criminal betrayal of a friend is perhaps the greatest shame Alfred Kroeber's memory shall have to bear. (Excerpt from Anthropology Answerable)

(May you make me happy!)excerpt from Crazy Devil Sweeping

[Note: In the occident reverence for the dead is not always a given fact. The irreverent treatment given Ishi’s remains evokes many similar cases in our culture, a long tradition of intellectual necrophilia, whether for reasons of dissection, religious mummification or sheer perverse curiosity. Perverse curiosity led to Mozart’s skull, dug up 10 years after his burial, being handled as a curio by many people for over 200 years after his death, to this very day. Mozart’s skull changed owners several times as a bauble that was bought and sold. After a century of such irreverent commerce, Mozart’s skull was put on display at the Mozart Museum in the city of his birth, Salzburg. It was on public display for 50 years, but today it is housed at the museum out of public view. Despite the fact that few if any people brought such glory to Austria as did Mozart, his memory is defiled by this academic necrophilia. It is like the supposed bones of Buddha that led to the founding of temples to house these relics, in total opposition to the Master’s teachings. After nearly 100 years, the American scientists came to their senses and allowed Ishi’s remains to be properly buried. 213 years after his death, Mozart has yet to be shown this respect in Austria.]

Update February 26, 2004

In his collection of Native Californian stories called Surviving Through the Days, Herbert W. Luthin presents his and Leanne Hinton’s translation of one of six stories Ishi told Edward Sapir in 1915: “A Story of Lizard.” Lizard was an expert arrow-maker, and Ishi, who was also an expert arrow-maker, may have identified with Lizard in this story. (Ishi’s arrowheads are among the finest in the collection at the Lowie Museum.) Luthin writes of the irony of Ishi being regarded as a “natural man”, when in truth he and his fellow Yahi who had survived terrifying American atrocities, lived in an unnatural manner, even while hiding in a natural wilderness for decades. Luthin continues: “The stress of that existence, a life of constant hardship and fear of discovery, is difficult for us even to imagine. […] But the life he knew was not the free, self-possessing, traditional existence of his ancestors; and it is a mistake to think that Ishi can represent for us – for anyone – some animisitic ‘free spirit’ or serve as a spokesman of untrammeled Native American life and culture.”

Ironically, Ishi may have had the most stress-free existence as a captive of the Americans for five years, in which, thanks to Kroeber and his other friends, he no longer suffered the anguish of running, hiding and worrying about being captured and put to death by Americans as happened to so many of his tribesmen.

Still another book on Ishi has been recently published, Ishi in Three Centuries (2003), a collection of 22 essays and testimonies edited by Karl Kroeber and Clifton Kroeber, sons of Alfred and Theodora Kroeber. In his review of this latest book on Ishi, Peter Nabokov has both praise and criticism to mete out. Nabokov remarks that previously unpublished material testifies that Ishi “was remarkbly intelligent, surprisingly sweet-tempered, and innately dignified, facing his fate with heartbreaking equanimity.” (News from Native California, Spring, 2004)

In this book we learn that at Ishi’s death, Alfred Kroeber’s first reaction was the right one: to totally forbid a scientific dissection of Ishi’s body. From Europe he wrote: ”We propose to stand by our friends. If there is any talk of the interests of science, then say for me that science can go to hell.” Had Kroeber stood firm in his resolve, posterity would not have subjected him to harsh condemnation for lack of character. Alas, he did not stand firm, and his words were mere talk, not backed up by action, or in this case, non-action. Ishi’s brain was sent to the Smithsonian Institution through the efforts of Kroeber, who chose not to stand by his friend.

Nabokov notes that the editors of Ishi in Three Centuries took every opportunity to put “family-or-profession-justifying spins” on their commentaries. “One gets the sticky impression that the Kroebers still regard Ishi’s legacy as something of a family franchise. Sometimes it seem’s the man’s dissection still goes on.” Nabokov continues: “Plowing through this book’s tortured arguments and reinterpretations, I could not help feeling that perhaps what Ishi most deserves now is silence.”

Amen. But I doubt that we are mature enough for this silence, as Ishi was mature in the sacred silence about his name. After centuries of trans-continental genocides, we need centuries to verbally deal with our collective shame and disgrace before we can rest in silence. My personal belief is that the epic crimes committed against Native Americans for long gruesome centuries cannot be expiated. Despite status as the only global super-power, high technology that produces atom bombs, sends men to the moon, and makes possible the overthrow of a foreign government at whim, the United States does not possess the power for expiating these genocidal crimes. Ishi’s enigmatic death mask smiles down at us as if saying: the gift of Turtle Island was bestowed on the Euro-Americans as pearls before swine.

A Report on Ishi's Treatment at the University of California, 1911-1916

| Home | Books | Sheet music for guitar | Visual arts | Biography | Syukhtun| Copyright © 2002 Syukhtun EditionsTM, All Rights Reserved

syukhtun.net domain name is trade marked SM , All Rights Reserved