|

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and is the largest one in the solar

system. If Jupiter were hollow, more than one thousand Earths could fit inside.

It also contains more matter than all of the other planets combined. It has a

mass of 1.9 x 1027 kg and is 142,800 kilometers (88,736 miles) across

the equator. Jupiter possesses 28 know satellites, four of which - Callisto,

Europa, Ganymede and Io - were observed by Galileo

as long ago as 1610. Another 12 satellites have been recently discovered and

given provisional designators until they are officially confirmed and named.

There is a ring system, but it is very faint and is totally invisible from the

Earth. (The rings were discovered in 1979 by Voyager 1.) The atmosphere is very

deep, perhaps comprising the whole planet, and is somewhat like the Sun. It is

composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, with small amounts of methane, ammonia,

water vapor and other compounds. At great depths within Jupiter, the pressure is

so great that the hydrogen atoms are broken up and the electrons are freed so

that the resulting atoms consist of bare protons. This produces a state in which

the hydrogen becomes metallic.

Colorful latitudinal bands, atmospheric clouds and storms illustrate

Jupiter's dynamic weather systems. The cloud patterns change within hours or

days. The Great Red Spot is a complex storm moving in a

counter-clockwise direction. At the outer edge, material appears to rotate in

four to six days; near the center, motions are small and nearly random in

direction. An array of other smaller storms and eddies can be found through out

the banded clouds.

Auroral

emissions, similar to Earth's northern

lights, were observed in the polar regions of Jupiter. The auroral emissions

appear to be related to material from Io

that spirals along magnetic field lines to fall into Jupiter's atmosphere.

Cloud-top lightning bolts, similar to superbolts in Earth's high atmosphere,

were also observed.

Jupiter's Ring

Unlike Saturn's intricate and complex ring patterns, Jupiter has a simple

ring system that is composed of an inner halo, a main ring and a Gossamer ring.

To the Voyager spacecraft, the Gossamer ring appeared to be a single ring, but

Galileo imagery provided the unexpected discovery that Gossamer is really two

rings. One ring is embedded within the other. The rings are very tenuous and are

composed of dust particles kicked up as interplanetary meteoroids smash into

Jupiter's four small inner moons Metis,

Adrastea, Thebe,

and Amalthea. Many of

the particles are microscopic in size.

The innermost halo ring is toroidal in shape and extends radially from about

92,000 kilometers (57,000 miles) to about 122,500 kilometers (76,000 miles) from

Jupiter's center. It is formed as fine particles of dust from the main ring's

inner boundary 'bloom' outward as they fall toward the planet. The main and

brightest ring extends from the halo boundary out to about 128,940 kilometers

(80,000 miles) or just inside the orbit of Adrastea. Close to the orbit of Metis,

the main ring's brightness decreases.

The two faint Gossamer rings are fairly uniform in nature. The innermost

Amalthea Gossamer ring extends from the orbit of Adrastea out to the orbit of

Amalthea at 181,000 kilometers (112,000 miles) from Jupiter's center. The

fainter Thebe Gossamer ring extends from Amalthea's orbit out to about Thebe's

orbit at 221,000 kilometers (136,000 miles).

Jupiter's rings and moons exist within an intense radiation belt of electrons

and ions trapped in the planet's magnetic field. These particles and fields

comprise the jovian magnetosphere

or magnetic environment, which extends 3 to 7 million kilometers (1.9 to 4.3

million miles) toward the Sun, and stretches in a windsock shape at least as far

as Saturn's orbit - a distance of 750 million kilometers (466 million miles).

| Jupiter Statistics |

| Mass (kg) |

1.900e+27 |

| Mass (Earth = 1) |

3.1794e+02 |

| Equatorial radius (km) |

71,492 |

| Equatorial radius (Earth = 1) |

1.1209e+01 |

| Mean density (gm/cm^3) |

1.33 |

| Mean distance from the Sun (km) |

778,330,000 |

| Mean distance from the Sun (Earth = 1) |

5.2028 |

| Rotational period (days) |

0.41354 |

| Orbital period (days) |

4332.71 |

| Mean orbital velocity (km/sec) |

13.07 |

| Orbital eccentricity |

0.0483 |

| Tilt of axis (degrees) |

3.13 |

| Orbital inclination (degrees) |

1.308 |

| Equatorial surface gravity (m/sec^2) |

22.88 |

| Equatorial escape velocity (km/sec) |

59.56 |

| Visual geometric albedo |

0.52 |

| Magnitude (Vo) |

-2.70 |

| Mean cloud temperature |

-121°C |

| Atmospheric pressure (bars) |

0.7 |

Atmospheric composition

- Hydrogen

- Helium

|

90%

10% |

Jupiter

Jupiter

This image was taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope on February 13, 1995. The

image provides a detailed look at a unique cluster of three white oval-shaped

storms that lie southwest (below and to the left) of Jupiter's Great Red Spot.

The appearance of the clouds, in this image, is considerably different from

their appearance only seven months earlier. These features are moving closer

together as the Great Red Spot is carried westward by the prevailing winds while

the white ovals are swept eastward.

The outer two of the white storms formed in the late 1930s. In the centers of

these cloud systems the air is rising, carrying fresh ammonia gas upward. New,

white ice crystals form when the upwelling gas freezes as it reaches the chilly

cloud top level where temperatures are -130°C (-200°F). The intervening white

storm center, the ropy structure to the left of the ovals, and the small brown

spot have formed in low pressure cells. The white clouds sit above locations

where gas is descending to lower, warmer regions.

The Interior

of Jupiter

The Interior

of Jupiter

This picture illustrates the internal structure of Jupiter. The outer layer is

primarily composed of molecular hydrogen. At greater depths the hydrogen starts

resembling a liquid. At 10,000 kilometers below Jupiter's cloud top liquid

hydrogen reaches a pressure of 1,000,000 bar with a temperature of 6,000° K. At

this state hydrogen changes into a phase of liquid metallic hydrogen. In this

state, the hydrogen atoms break down yeilding ionized protons and electrons

similar to the Sun's interior. Below this is a layer dominated by ice where

"ice" denotes a soupy liquid mixture of water, methane, and ammonia

under high temperatures and pressures. Finally at the center is a rocky or

rocky-ice core of up to 10 Earth masses. (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Thin

Crescent Image of Jupiter

Thin

Crescent Image of Jupiter

This thin crescent picture of Jupiter was created from a photomosaic of images

Galileo took on its C9 orbit. It is made from Near Infrared and Violet images,

with an artificial green image produced from the other two. (Courtesy of Ted

Stryk)

Nordic

Optical Telescope

Nordic

Optical Telescope

This image of Jupiter was taken with the 2.6 meter Nordic

Optical Telescope, located at La Palma, Canary Islands. It is a good example

of the best imagery that can be obtained from earth based telescopes. (c) Nordic

Optical Telescope Scientific Association (NOTSA).

Jupiter with

Satellites Io and Europa

Jupiter with

Satellites Io and Europa

Voyager 1 took this

photo of Jupiter and two of its satellites (Io,

left, and Europa, right)

on Feb. 13, 1979. In this view, Io is about 350,000 kilometers (220,000 miles)

above Jupiter's Great Red Spot, while Europa is about 600,000 kilometers

(373,000 miles) above Jupiter's clouds. Jupiter is about 20 million kilometers

(12.4 million miles) from the spacecraft at the time of this photo. There is

evidence of circular motion in Jupiter's atmosphere. While the dominant large

scale motions are west-to-east, small scale movement includes eddy like

circulation within and between the bands. (Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Satellite

Footprints Seen in Jupiter Aurora

Satellite

Footprints Seen in Jupiter Aurora

In this Hubble Space Telescope picture, a curtain of glowing gas is wrapped

around Jupiter's north pole like a lasso. This curtain of light, called an

aurora, is produced when high-energy electrons race along the planet's magnetic

field and into the upper atmosphere where they excite atmospheric gases, causing

them to glow. The aurora resembles the same phenomenon that crowns Earth's polar

regions. But this Hubble image, taken in ultraviolet light, also shows the

glowing "footprints" of three of Jupiter's largest moons: Io,

Ganymede, and Europa.

Courtesy of NASA/ESA, John Clarke (University of Michigan)

Jupiter's

Magnetosphere

Jupiter's

Magnetosphere

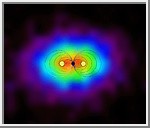

This image taken by the ion and neutral mass spectrometer instrument on NASA's

Cassini spacecraft makes the huge magnetosphere surrounding Jupiter visible in a

way no instrument on any previous spacecraft has been able to do. The

magnetosphere is a bubble of charged particles trapped within the magnetic

environment of the planet. A magnetic field is sketched over the image to place

the energetic neutral atom emissions in perspective. This sketch extends in the

horizontal plane to a width 30 times the radius of Jupiter. Also shown for scale

and location are the disk of Jupiter (black circle) and the approximate position

(yellow circles) of the doughnut-shaped torus created from material spewed out

by volcanoes on Io.

Some of the fast-moving ions within the magnetosphere pick up electrons to

become neutral atoms, and once they become neutral, they can escape Jupiter's

magnetic field, flying out from the magnetosphere at speeds of thousands of

kilometers, or miles, per second.

Jupiter's

Auroras

Jupiter's

Auroras

These HST images, reveal changes in Jupiter's auroral emissions and how small

auroral spots just outside the emission rings are linked to the planet's

volcanic moon, Io. The top

panel pinpoints the effects of emissions from Io. The image on the left, shows

how Io and Jupiter are linked by an invisible electrical current of charged

particles called a flux tube. The particles, ejected from Io by volcanic

eruptions, flow along Jupiter's magnetic field lines, which thread through Io,

to the planet's north and south magnetic poles.

The top-right image shows Jupiter's auroral emissions at the north and south

poles. Just outside these emissions are the auroral spots called

"footprints." The spots are created when the particles in Io's

"flux tube" reach Jupiter's upper atmosphere and interact with

hydrogen gas, making it fluoresce.

The two ultraviolet images at the bottom of the picture show how the auroral

emissions change in brightness and structure as Jupiter rotates. These

false-color images also reveal how the magnetic field is offset from Jupiter's

spin axis by 10 to 15 degrees. In the right image, the north auroral emission is

rising over the left limb; the south auroral oval is beginning to set. The image

on the left, obtained on a different date, shows a full view of the north

aurora, with a strong emission inside the main auroral oval.

Credits: John T. Clarke and Gilda E. Ballester (University of Michigan),

John Trauger and Robin Evans (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), and NASA.

The

Great Red Spot

The

Great Red Spot

This dramatic view of Jupiter's Great Red Spot and its surroundings was obtained

by Voyager 1 on Feb. 25, 1979, when the spacecraft was 9.2 million kilometers

(5.7 million miles) from Jupiter. Cloud details as small as 160 kilometers (100

miles) across can be seen here. The colorful, wavy cloud pattern to the left of

the Red Spot is a region of extraordinarily complex and variable wave motion. (Courtesy

NASA)

False Color

of Jupiter's Great Red Spot

False Color

of Jupiter's Great Red Spot

This image is a false color representation of Jupiter's Great Red Spot taken

with Galileo's imaging system through three different near-infrared filters.

This is a mosaic of eighteen images (6 in each filter) that were taken over a

period of 6 minutes on June 26, 1996. The Great Red Spot appears pink and the

surrounding region blue because of the particular color coding used in this

representation. The red channel is the reflectance of Jupiter at a wavelength

where methane strongly absorbs (889nm). Because of this absorption, only high

clouds can reflect sunlight in this wavelength. The green channel is the

reflectance in a wavelength where methane absorbs, but less strongly (727nm).

Lower clouds can reflect sunlight in this wavelength. Finally, the blue channel

is the reflectance in a wavelength where there are essentially no absorbers in

the Jovian atmosphere (756nm) and one sees light reflected from the deepest

clouds. Thus, the color of a cloud in this image indicates its height, with red

or white being highest and blue or black being lowest. This image shows the

Great Red Spot to be relatively high, as are some smaller clouds to the

northeast and northwest that are surprisingly like towering thunderstorms found

on earth. The deepest clouds are in the collar surrounding the Great Red Spot,

and also just to the northwest of the high (bright) cloud in the northwest

corner of the image. Preliminary modelling shows these cloud heights to range

about 50km in altitude. (Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Ring

of Jupiter

Ring

of Jupiter

The ring of Jupiter was discovered by Voyager 1 in March of 1979. This image was

taken by Voyager 2 and has been pseudo colored. The Jovian ring is about 6,500

kilometers (4,000 miles) wide and probably less than 10 kilometers (6.2 miles)

thick. (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

The Jovian

System

The Jovian

System

The best of the Jupiter system is pictured in this collage of images acquired by

the Voyager and Galileo spacecraft. Jupiter is the largest planet in our solar

system. The four largest moons of Jupiter are known as the Galilean moons and

are named Callisto, Ganymede,

Europa, and Io.

Inside the orbits of the Galilean moons are Thebe,

Amalthea, Adrastea,

and Metis. At the lower

right is shown the Valhalla region of Callisto. Ganymede is toward the bottom

middle. Europa is a little above and to the right of Ganymede. Io is the top,

left-most moon. Between Io and Jupiter are four little moons. The top-most

little moon is Amalthea. Below and to the right of Amalthea are Metis and

Adrastea. To the left of Adrastea is Thebe. (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Moons of

Jupiter

Moons of

Jupiter

This image shows to scale Jupiter's moons Amalthea,

Io, Europa,

Ganymede, and Callisto.

(Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

| Name |

Distance* |

Width |

Thickness |

Mass |

Albedo |

| Halo |

92,000 km |

30,500 km |

20,000 km |

? |

0.05 |

| Main |

122,500 km |

6,440 km |

< 30 km |

1 x 10^13 kg |

0.05 |

| Inner Gossamer |

128,940 km |

52,060 km |

? |

? |

0.05 |

| Outer Gossamer |

181,000 km |

40,000 km |

? |

? |

0.05 |

*The distance is measured from the planet center to the start of the ring.

Nearly four centuries ago Galileo Galilei turned his homemade telescope

towards the heavens and discovered three points of light, which at first he

thought to be stars, hugging the planet Jupiter. These stars were arranged in a

straight line with Jupiter. Sparking his interest, Galileo observed the stars

and found that they moved the wrong way. Four days later another star appeared.

After observing the stars over the next few weeks, Galileo concluded that they

were not stars but planetary bodies in orbit around Jupiter. These four stars

have come to be know as the Galilean

satellites.

Over the course of the following centuries another 12 moons were discovered

bringing the total to 16. Another 12 satellites have been recently discovered

and given provisional designators until they are officially confirmed and named.

Finally in 1979, the strangeness of these frozen new worlds was brought to light

by the Voyager spacecrafts as they swept past the Jovian system. Again in 1996,

the exploration of these worlds took a large step forward as the Galileo

spacecraft began its long term mission of observing Jupiter and its moons.

Twelve of Jupiter's moons are relatively small and seem to have been more

likely captured than to have been formed in orbit around Jupiter. The four large

Galilean moons, Io, Europa,

Ganymede and Callisto,

are believed to have accreted

as part of the process by which Jupiter itself formed. The following table

summarizes the radius, mass, distance from the planet center, discoverer and the

date of discovery of each of the moons of Jupiter:

| Moon |

# |

Radius

(km) |

Mass

(kg) |

Distance

(km) |

Discoverer |

Date |

| Metis |

XVI |

20 |

9.56e+16 |

127,969 |

S. Synnott |

1979 |

| Adrastea |

XV |

12.5x10x7.5 |

1.91e+16 |

128,971 |

Jewitt-Danielson |

1979 |

| Amalthea |

V |

135x84x75 |

7.17e+18 |

181,300 |

E. Barnard |

1892 |

| Thebe |

XIV |

55x45 |

7.77e+17 |

221,895 |

S. Synnott |

1979 |

| Io |

I |

1,815 |

8.94e+22 |

421,600 |

Marius-Galileo |

1610 |

| Europa |

II |

1,569 |

4.80e+22 |

670,900 |

Marius-Galileo |

1610 |

| Ganymede |

III |

2,631 |

1.48e+23 |

1,070,000 |

Marius-Galileo |

1610 |

| Callisto |

IV |

2,400 |

1.08e+23 |

1,883,000 |

Marius-Galileo |

1610 |

S/1975 J1

S/2000 J1 |

|

4 |

? |

7,435,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| Leda |

XIII |

8 |

5.68e+15 |

11,094,000 |

C. Kowal |

1974 |

| Himalia |

VI |

93 |

9.56e+18 |

11,480,000 |

C. Perrine |

1904 |

| Lysithea |

X |

18 |

7.77e+16 |

11,720,000 |

S.

Nicholson |

1938 |

| Elara |

VII |

38 |

7.77e+17 |

11,737,000 |

C. Perrine |

1905 |

| S/2000 J11 |

|

2 |

? |

12,654,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| S/2000 J10 |

|

1.9 |

? |

20,375,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| S/2000 J3 |

|

2.6 |

? |

20.733,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| S/2000 J5 |

|

2.2 |

? |

21,019,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| S/2000 J7 |

|

3.4 |

? |

21,162,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| Ananke |

XII |

15 |

3.82e+16 |

21,200,000 |

S. Nicholson |

1951 |

| S/2000 J9 |

|

2.5 |

? |

21,734,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| S/2000 J4 |

|

1.6 |

? |

21,948,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| Carme |

XI |

20 |

9.56e+16 |

22,600,000 |

S. Nicholson |

1938 |

| S/2000 J6 |

|

1.9 |

? |

22,806,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| Pasiphae |

VIII |

25 |

1.91e+17 |

23,500,000 |

P. Melotte |

1908 |

| S/2000 J8 |

|

2.7 |

? |

23,521,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

| Sinope |

IX |

18 |

7.77e+16 |

23,700,000 |

S. Nicholson |

1914 |

| S/2000 J2 |

|

2.6 |

? |

24,164,000 |

Sheppard et al |

2000 |

S/1999 J1

1999 UX18 |

|

2.4 |

? |

24,296,,000 |

Spacewatch |

1999 |

|