LINKS :

A) Four-Stroke Cycle

The overwhelming

majority of car engines still employ the four-stroke cycle (four piston strokes

per cycle), invented by Nicholas Otto in 1876.

The first downstroke of the piston

that is attached to a connecting rod at its top end and to the crankshaft at the

bottom, draws a petrol-air mixture into the cylinder. This is then compressed,

which is the second stage of the process. The volatile cocktail is then ignited

by a sparking plug and the resulting explosion forces down the piston, so

turning the crankshaft. The final phase of the operation is the stroke that

expels the exhaust gases from the cylinder.

B)

Cylinder Head

The engineís cylinder block is

invariably made of cast iron on to which is bolted an aluminium cylinder head.

This contains the valves that permit the petrol-air mixture to enter the

combustion chamber and the exhaust gases to leave it. These can be actuated by

pushrods from a block-located crankshaft-driven camshaft, although the head more

usually incorporates single or twin "overhead" camshafts driven by a ribbed

rubber belt.

C)

Fuel Injection

A carburettor had been used from

the earliest days of motoring as a component in which the petrol-air mixture was

created. The limitation of such an arrangement was that the mixture was unevenly

distributed which resulted in incomplete combustion and an undesirable amount of

unburnt fuel reaching the atmosphere.

As a result, the carburettor has

now been replaced by fuel injection. This first appeared on high-performance

cars in the 1950s. Not only is a precise amount of metered petrol delivered by

pump to each cylinder, but the air supply can also be carefully controlled by

the use of an individual inlet manifold.

D)

Lubrication

An engine cannot function unless

it is well lubricated with oil. This is circulated under pressure from a pump

that draws lubricant from a reservoir contained within the sump at the base of

the engine. It is delivered under pressure to the main crankshaft bearings from

a gallery located in the side of the block, and to the appropriately named

big-ends of the connecting rods via holes drilled in the shaft. Oil reaches the

bores by splash although it is pumped to the camshaft and valve gear.

E)

Cooling

As the combustion temperature of

petrol is 2500į C, the engine must be cooled. The cylinders and head therefore

incorporate water jacketing for a coolant that contains an antifreeze mixture

circulated by pump. It is cooled in a radiator located at the front of the car

by a passage of air that is drawn through it by a thermostatically operated

electric fan.

F)

Ignition

Whether a carburettor or fuel

injection is employed, the petrol-air mixture has to be ignited by a sparking

plug. Current is fed to each via a distributor supplied from a high-tension

coil. The current requires interruptions in its cycle, and these are produced by

a contact breaker contained within the distributor. Nowadays, more efficient

contactless distributors are employed that work in conjunction with a

computerized engine management system.

G)

Electrical Equipment

The carís management system is yet

another component to make demands on the carís battery. The system is charged by

an engine-driven alternator that, unlike the dynamo it replaced in the 1970s, is

efficient at low speeds or when a car is "ticking over" in a traffic queue.

A key function of the electrical system is to start the carís engine. This is usually undertaken by a pre-engaged motor, in which a solenoid moves a bevel gear into mesh with the teeth on the engineís flywheel. In addition to providing current for the carís lights and windscreen wipers, modern electrical systems have to service a radio/tape recorder, cigarette lighter, heated rear window, central door locking, windows, air conditioning, and, more recently, seat adjustment.

H) Manual Transmission On most front- and rear-drive cars the gearbox is attached directly to the engine. To facilitate gear changing, the drive passes through a clutch that must be briefly disengaged by the driver. This detaches the componentís pressure plate from the driven one.

The gearbox usually incorporates four or five forward speeds and reverse. It consists, in essence, of three lines of gear clusters, all of which are in constant engagement. There is a short first-motion shaft, connected to an output shaft, that meshes with an offset layshaft. The changes are effected by sliding dog clutches positioned on the combined first-motion/output shaft. This also incorporates synchromesh cones, which facilitate silent gear changes.

I)

Automatic Transmission

This works in conjunction with a

torque converter or fluid flywheel, which transmits the engineís power through

the medium of hydraulic fluid to the automatic gearbox. It accordingly does not

require a clutch pedal.

An automatic unit is far more complex than a manual one and has at its heart a series of epicyclic gears, which are selected mechanically. Changes are effected automatically by a complex sequence of hydraulically controlled commands.

A simpler system that makes fewer demands on the engine, and is therefore more economical, is continual variable transmission. This initially used rubber belts in conjunction with pulleys that expanded and contracted to alter the engineís power ratios. On the current version, however, this function is undertaken by a steel belt.

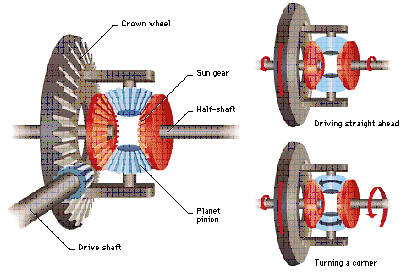

J)

Drive Lines

In a front-wheel drive car, power

is conveyed by gearing to a differential that is incorporated in the

engine/gearbox unit. Its function is to permit cornering so that the

outer-driven wheel turns faster and further than the inner one. Drive is

transferred to each wheel by a constant velocity joint that can also absorb

steering forces.

On a rear-drive vehicle, power is transmitted from the gearbox to the rear-located differential via a propeller shaft. It is then conveyed to the wheels by half-shafts (in the case of a live rear axle) or universally jointed drive shafts (if independent rear suspension is employed).

K)

Independent Suspension

The arrival of front-wheel drive

saw an increase in the use of independent front suspension, in which each wheel

is able to act in isolation to the other. One of its most important advantages

is that it keeps the wheels vertical and the tyres on the highway, regardless of

body roll, and therefore enhances the carís road-holding ability. The most

common version employs two unequal length "wishbones", with coil springs

providing the suspension medium. In the alternative MacPherson strut system

there are no wishbones and the spring is combined with a shock absorber.

L)

Brakes

Most cars use disc brakes on their

front wheels; these are fitted on front and back wheels on more expensive

models. When the brake pedal is applied, hydraulic power is applied to calipers

that grip the disc and so contribute to arresting the carís progress. Drum

brakes, that use internally actuated shoes, are often fitted at the rear. All

cars feature a hand or parking brake that operates on the vehicleís rear brake

shoes or discs.

M) Steering The most popular steering system is rack and pinion. Power-assisted steering, which is hydraulically activated by an engine-driven pump and previously the preserve of expensive cars, is becoming increasingly popular.

N)

Bodywork

A bodyís aerodynamic efficiency is

measured by drag coefficient (Cd) and the lower the figure the greater the carís

wind cheating properties. Nowadays, most cars register a reading of 0.3 to 0.4

and such features as integrated bumpers, a tapered nose, and windows that are

flush with the body sides are incorporated to keep a vehicleís Cd as low as

possible.

As a result the Cd of a typical family car can be superior to that of some performance models. The Ford Mondeo and Vauxhall Vectra have Cd readings of 0.31 and 0.28 respectively, while the current version of Porscheís long-running 911 sports cars registers 0.33.

O)

Saloon Bodies Most cars were fitted with open, wooden-framed, hand-crafted steel or aluminium bodywork that was mounted on a separate chassis frame. Saloons were more expensive because they used more materials. It was not until 1925 that the American Essex company risked all by offering a closed car that sold for less than a touring vehicle. The gamble paid off and the rest of the motoring world soon followed suit.Machine-made pressed steel body panels had been used by Dodge in America from 1916; this led to the all-steel saloon and, finally, the unitary body, which dispensed with the chassis and transferred stresses to the hull. CitroŽnís advanced front-wheel drive Traction Avant model of 1934 was the first mass-produced car to feature the concept and was followed by General Motorsí German Opel subsidiary in 1935. General Motors was also responsible for introducing silent gear changes to motoring in 1928, and in 1940 an American car, the Oldsmobile, was the first vehicle to have automatic transmission.

Cars used leaf springs inherited from horse-drawn carriages until the 1930s, when independent front suspension was developed. However, its rear equivalent was rarer and usually confined to more expensive vehicles. An exception was provided by Volkswagen AG in Germany. The Beetle was the Volkswagen which was designed by Ferdinand Porsche in 1934 and entered series production in 1945. Featuring all-independent suspension, it was powered by a rear-mounted, horizontally opposed, four-cylinder engine that was cheap to run, and which also defied convention by being air- rather than water-cooled. The Beetle became the most popular car in the history of motoring; it is still in production and a record 21 million have been built.

A German company also produced the economical and efficient diesel engine, invented in 1893 by Rudolf Diesel. Adopted in the 1920s for use in commercial vehicles, in 1935 Mercedes-Benz introduced the 260D as the worldís first diesel-engined car.

P) Front-Wheel Drive In 1937 the French CitroŽn company briefly offered a diesel option in its front-wheel drive Traction Avant. This model represented the first serious challenge to the orthodox front-engine/rear-drive configuration. Although the mechanics were more sophisticated, the Traction Avant cornered better and could be built with lower body lines because there was no obtrusive transmission tunnel.

While the CitroŽnís engine was conventionally positioned, the British Motor Corporationís front-wheel drive Mini of 1959, designed by its chief engineer Alec Issigonis, had its power unit turned 90į to a transverse-mounted location. This allowed for more passenger accommodation: four adults could be seated in a car only 3 m (10 ft) long.