...HAS CROSSED THE SEA...

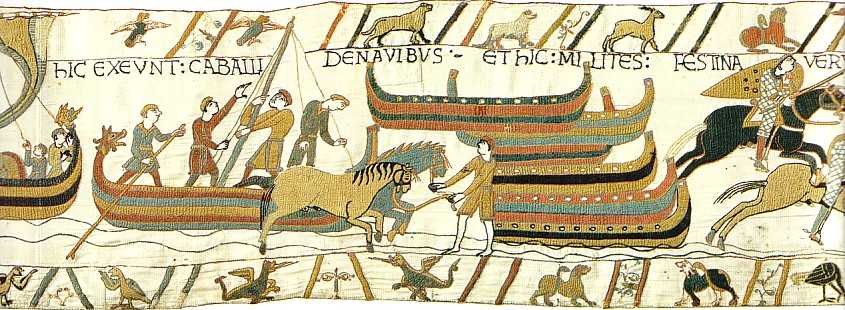

I appreciate the attempt here to portray an immense fleet. The little ships in the background add a perspective of depth, showing how hundreds of vessels spread out across the Channel. I think the most enlightening detail here is the transportation of the horses. Obviously, the fact that horse heads only are visible indictates that the shallow draft of the typical north Atlantic longship was not prefered for the horse transports. Most of William's built ships must have been specially designed to carry horses. Some are packed with eight or ten, most with only three or four. This could only be artistic licence, but I believe if the horses were typically exposed in the midships of a shallow draft boat they would have been depicted that way. To keep them under control there must have been stalls built for them to stand in.

Even though many ships show oar tholes, those carrying horses would have found the use of oars impossible. Putting out an oar to maneuver would still be possible, just not rowing by a crew. The hanging shields at bow and stern are clearly shown here attached by their guige straps.

...AND COME TO PEVENSEY

The ship with the cross-shaped lantern on the mast (yet another sign of William's religious favor) has usually been associated as William's flagship the Mora: it is certainly the most fancy, with a trumpet-blowing boy on the stern post and a dragon prow. Any number of other ships would also have carried lanterns and torches to help the fleet stay together during the night passage of the 27-28 September.

The gunwales of some ships - e. g. the Mora - are lined with shields like viking warships. I believe these are meant to be purely troop transports. In the event of a contested passage of the Channel, these vessels would have been free of horses or supplies to maneuver into combat with king Harold's fleet.

But in fact, his troops had eaten up all their supplies and gone home. The fleet had returned to London, from whence Harold had mustered his army to march into the north to face down king Harald Hardrada of Norway and Harold's brother Tosti. Their army had invaded Northumbria and defeated the brother earls Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the battle of Gate Fulford. While William's fleet was waiting to cross the Channel, Harold's army was drawing near York - and three days before the Norman army disembarked at Pevensey and Hastings, he fought the viking invaders on 25 September and won a complete victory at the battle of Stamford bridge. Tosti, who had been exiled the year before because of rebellions against his oppressive government in Northumbria, was killed along with the Norse king.

HERE THE HORSES ARE GETTING OUT OF THE BOATS - AND HERE THE KNIGHTS...

So there was no English army to oppose William's landing. It is usually accepted that the main army landed at Hastings, while a mounted portion disembarked their horses at Pevensey and rode to Hastings on a reconnoitering mission, and to forage. A ruined Roman castle was at Pevensey, and a garrison was put into a motte-and-bailey built inside the circuit of its walls.

The horses are shown leaping out of the ships. The technical side of this operation is missing. If the boats had shallow draft, this would be possible as shown; but if high-sided, there must have been ramps employed. I think a combination of both methods was used: for it is doubtful that all the horses could have enjoyed the passage in special horse transports, and many knights must have braved the Channel in lesser ships. To get the horses out, the keel would be run up on the sand, the horses would be led to one side, the water would come over the gunwale, partially swamping the ship and lowering it, allowing the horses to jump out easily.

The masts are stepped and the ships drawn out of the water in a close line.