|

M. R. Shafi'i-Kadkani

(Iran) |

Borbad's Khusravanis-First Iranian Songs

Finding the beginning of Persian poetry, as is the case for finding the first poem in any language, is an ongoing concern. Can we really conceptualize mankind apart from his poetry? After all, poetry is the essence of his thoughts. It is his way of relating to nature. Poetry is akin to his being. How can we separate him from his spirituality?

In fact, the story of poetry falls outside the purview of history per se, making any attempt at determining the first poem for any language futile. Poetry begins with the movement of the first caravan-it is, as it were, the sound of the bell on the leading camel. That is why the title of the first poem and the identity of the first poet will have to remain unknown. The story of Adam's composition of an elegy after the death of his son (killed by his other son) is a legend. The fact that it is reported by Islamic historians does not make it any more credible. There are, however, certain things that can be asserted with certainty. For instance, based on ancient sources, we can assert that Persian poetry is rooted in the hymns of Zoroaster, the Gathas, the religious songs of the Iranians, as well as in the rest of the Avesta This discussion, too, although widely examined, remains inconclusive. It is claimed that Dari poetry appeared after the Arab invasion and that as long as there is no supporting evidence to the contrary, that remains the case. In support of this claim, the poems of Abu Hafs-i Sughdi, Abu al-Abbas-i Marvazi, and those of the Arab poet, Yazid Ibn-i Mifraq are presented as evidence. Obviously, were we to limit Dari poetry to post-Sassanian times, we would have no option but to choose the first poem from among the works of these poets.

Allamah Qazvini has presented a lengthy discussion of this subject in twenty essays. But his views, too, are focused on these same few specimens.

|

According to our best information, this is an example of the oldest Dari poem, older even than that of Ibn-i Mifraq, because the story it tells precedes Ibn-i Mifraq in time.

We cannot, therefore, distinguish Dari as a post-Sassanian phenomenon; the ancient quality of its poetry does not allow that. The theories thus far have tried to establish Dari as a continuation of Pahlavi Middle .

But we understand now that the Dari language had been a language spoken alongside Pahlavi Middle Persian at the courts of the eastern Iranian kings. Ibn-i Muqaffa', quoting Ibn-i Nadim and Hamza-i Isfahani in Al-Tanbih Ala Huduth al-Tashif, and Yaqut Humavi in Mu'jam al-Buldan have made references to this fact.They speak of Dari as a language, with its own literature, spoken during late Sassanian and early Islamic times.In addition to historical facts, the same information can be deduced from a linguistic analysis of the poems and from investigating the history of Persian literature after the Arab invasion. The very eloquence of poets like Rudaki and authors like bespeaks the status of Dari as a language that had been in use for quite some time. How else could it soar to the heights it did within only a couple of centuries?

Further support can be found in Dari quotations attributed to Sassanian monarchs in such Arabic works as Al-Mahasin wa al-Azdad of Jahiz.Can we ignore all this evidence and limit the poetry in the Dari language to the era after the Arab invasion? If the language was in use, it must have had its own poetry. We may not have access to a sample of that poetry, but should this lack of access compel us to deny the existence of the poetry as well?

Islamic historians like Mas'udi in Al-Tanbih wa al-Ashraf and Abu Hilal Askari in Al-Tafsil bain al-'Arab wa al-Ajam point to a wealth of poetry during the Sassanian era. We do not know, however, how much of this poetry had been in Dari and how much in Pahlavi Middle . The sources are silent on the distinction. We have only Malak al-Shu'ara Bahar's statement made on the basis of the Turfan finds. In his articles entitled "Shi'r dar Iran," in Mihr, he states that the poetry referred to was in Dari because he detected certain differences between the language of that poetry and Pahlavi Middle . Furthermore, that language contained some vocabulary that is absent in Pahlavi Middle . Safa, on the other hand, assigns these works to Parthian (northern) and Sassanian (southern) Pahlavi. The language of these fragments is still being debated but, most likely, it is Pahlavi. To my knowledge Bahar's is the only reference to Dari poetry during Sassanian times. This, of course, throws doubt on the poetry ascribed to Bahram-i Gur and Huma-i Chihrzad.

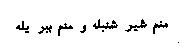

The poem ascribed to Bahram had been doctored. If it was not for Ibn-i Khurdadbih's statement in Al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik, we could consider it a figment of the imagination of the historians and story tellers. But we have to give some weight to Ibn-i Khurdadbih's statement that the following had existed:

|

However, most scholars do not accept the Dari ascription and consider this poem to be in heptameter, i.e., containing seven syllabic feet.

The Surud-i Karkui, too, in spite of Bahar's ascription of Dari to it,and in spite of the poem's originality, cannot be considered Dari as long as the time of its composition is debatable. Conjecture places it after the Arab conquest but, even then and even if we accept it as Dari, it is not the oldest. We must search for even more ancient specimens. As mentioned, Tarikh-i Qum and Mujmal al-Tawarikh record some poems ascribed to Huma-i Chihrzad and Ardashir-i Babakan but, if these were Dari verses, why are there no mentions of them in our literary histories?We know that before the Arab invasion, Persian verse, being syllabic, did not conform to the Arabic metric system. Those familiar with the Arabic meters, considered the syllabic verse to be a kind of prose. That is why Awfi, who was familiar with the Arabic metric system, assessed Bahram's syllabic verse as follows: "He [Bahram] was the first to compose poetry in Persian. During the time of Parviz many such compositions existed and were put to music by Borbad.

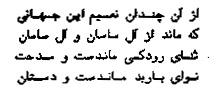

But, since these poems are devoid of meter, rhyme, and the other trappings of poetry, we have not dealt with them in any substantial manner."This statement indicates that even at the time of Awfi some form of the syllabic verse was still in existence. The frequent references to the songs of Borbad and Nakisa in Persian, during early Islamic times, is indicative of the prevalence of this kind of verse at that time. Furthermore, there are documents indicating that Borbad's verses had been published at that time. The following poem of Mujladi (or Makhlidi) Gurgani, who lived at the end of the 4th or beginning of the 5th century AH, is indicative of that:

|

Regarding this Edward states: "There can be no doubt that Sassanian courts were filled with music and with songs and that the trend was, at the least, reflected in post-Sassanian times. No matter how drastically the change to a metric system may have affected the syllabic poetry of ancient Iran, at least superficially, the quatrain and the ode are Iranian in origin."

Elsewhere says, "Although Persian poetry reached its apogee in the 10th century in Khurasan, ... there is a story that indicates its existence at the Sassanian courts. This story is repeatedly recorded in trusted ancient sources, only the name of the musician takes various forms. The difference is, perhaps, in the rendition of the Pahlavi form. I cannot but say that the subject calls for deeper investigation."The above statements indicate that the Farsi language had been spoken at the Sassanian court alongside Pahlavi, that it had been a literary language with its own verse form, and that in later (i.e., post-Sassanian times it had appeared as Dari. One of the examples of poetry of this period frequently discussed by the literary sources, is the songs of Borbad, musician, performer, and theoretician. He lived at the time of Khusrau Parviz and there are many references to his legend in the literature of subsequent centuries.

Christensen says, "Burhan-i Qati' mentions thirty songs that had been composed by Borbad for Khusrau Parviz. The same statement is repeated in Nizami's Khusrau and Shirin with a slight discrepancy. Ascribing the Khusravanis to Borbad, Tha'alibi says that even during his time, musicians performed the khusravanis in the festivities sponsored by the kings and others. In fact, khusravani has not been just one song or melody. Awfi refers to khusravani in the sense of the Seven Royal Dastgahs which Mas'udi calls al-Turuq al-Mulukiyyah..."

These seven rah's are mentioned by both Mas'udi and Ibn-i Khurdadbih. Mas'udi, however, gives the number to be seven, while Ibn-i Khurdadbih gives eight.Before producing samples of the khusravaniyyat, i.e., poetry that is syllabic and possibly written in Dari, we shall first proceed to examine the khusravaniyyat genre. Bahar recognizes them as poems written in praise of kings, mu'bads, God, and the temple of fire. They are referred to as surud (songs) or khusravani songs.

Huma'i recognizes the khusravanis as a type of rhymed verse composed by Borbad in praise of Khusrau Parviz. They were sung with a special melody. Nasir al-Din Tusi, in Asas al-Iqtibas, refers to them as a kind of pseudo-metric verse. He distinguishes them as forms composed of equal syllables resembling metric verse compositions. The Tarikh-i Sistan relates the Persian language to music and the writer of al-Mu'jam speaks about Borbad (from Jahrum) as a master musician composing poetry for Khusrau Parviz's festivities. Even though the entire composition is in praise of Khusrau Parviz, he says, it is recited in prose. And Abu Hilal Askari says the following in his al-Sana'atain about khusravani. It is a melody in present-day Farsi wherein the words are used in a non-verse composition. They are poems which can be classified as such only due to the lengthening applied to otherwise simple prose forms."Lughatnama-i Dehkhuda, Burhan-i Qati', Anandraj, Qiyas al-Lughat, Anjuman Ara, and Mahshi al-Lughat all support the statements presented above.

Furthermore, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales (M. Omid) presents a comprehensive and well-documented survey in Yaghma of the khusravanis. Unfortunately, he does not produce any samples and rests his case mostly on Bahar's assertions regarding the poetry of the Samanid poet Abu Talib Tayyib Ibn-i Muhammad in Lughat-i Furs-i Asadi. In other words, he guesses. In any event, as long as the form belongs to post-Sassanian times, we should be on the lookout for a more ancient specimen.There is a stanza in Ibn-i Khurdadbih's Mukhtarat min Kitab al-Lahv wa al-Malahi that, I believe, deserves particular attention. Ibn-i Khurdadbih, of course, is known for his contribution to history, geography, and music during the third century AH. The piece is ancient and is presented by a student of Ishaq Musili, a student well-versed in the history of Persian music.

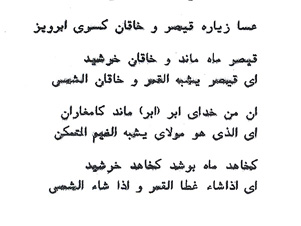

Further support for the credentials of Musili is found in Mas'udi's Muravvij al-Zahab. Mas'udi explains how Musili appeared at the court of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu'tamid and was commissioned to lecture on international music.In this book, the original of which is no longer extant, but excerpts of which have survived and have recently been published, we read: "...the greatest Iranian musician at the court of Khusrau Parviz has been Bahlbad (Borbad) from Ray, a skilled lute player who composed songs, played music, and sang songs for Khusrau Parviz. Often he communicated the more distressing items of news, news that others did not dare mention to Khusrau, by incorporating such news in his songs. Altogether, fifty such songs are recognized. The following is an example:

|

Even without the Arabic translation, a present-day Iranian understands this poem.

is, of course, "cloud" as attested by

is, of course, "cloud" as attested by  and

and  is

is  . The problematic part is, perhaps, the introductory phrase that could mean "At the time of visiting the Caesar, Khaqan, King of Kings Parviz. It is not a part of the poem because, unlike the hemstitches of the poem, it does not have an original form.

. The problematic part is, perhaps, the introductory phrase that could mean "At the time of visiting the Caesar, Khaqan, King of Kings Parviz. It is not a part of the poem because, unlike the hemstitches of the poem, it does not have an original form.

Returning to the piece itself, each hemstitch consists of 10-11 syllables. We cannot give an exact number, of course, because we don't know how the poem-with long and short syllables-was read at that time.

The discovery of this poem not only provides us with an ancient poetic form that harks to the time of Khusrau Parviz, but it also throws light on some other issues as well. The first is a recognition of the syllabic nature of the poetry of that time. Literary historians unfamiliar with the metric system mistook it for prose used by Borbad as the base for his compositions. Only Nasir al-Din , who was familiar with the syllabic system, refers to khusravaniyyat as a type of pseudo-metric form.

Of course, on the basis of this single verse, we cannot posit that poetry in ancient times was exclusively syllabic. This poem only confirms that the metric verse was introduced into Iran by the Arabs.

It also rejects Huma'i's view that posits the existence of a metric system for Sassanian times. Although in defense of Huma'i, we should add that he does not state this position firmly, rather, he makes inferences on the basis of music. Finally, this poem supports the statement of Ibn-i Muqaffa' and Hamza-i Isfahani, and others that the Dari language was spoken atthe court of the Sassanians and that it had its own literature and songs.

| Ma'ruf

(Tajikistan) |

The Musical Culture of Iran at the Beginning of the Middle Ages

Manuscripts play a crucial role in research by revealing important data regarding the various aspects of Iranian and, indeed, Tajik civilizations. Based on sources written in different languages and in varied contexts-literary, geographical, or religious-researchers can formulate specific views regarding the political, economic, social, cultural, and civilizational aspects of historical eras. Translations of Arabic sources into Perso-Tajik which were commissioned by scholars, nobles, and wazirs of the Samanid era (AD 874-999) deal with the history of Iran at the time of the Sassanids (AD 224-651). The relations between the Iranians and the Hephthalites of Varazrud and Khurasan, including military, political, economic, and cultural ties during the fourth to sixth centuries fall within this time period. During the Samanid era, authors, copyists, and translators paid special attention to the ethnic ties, geographic boundaries, languages and, in particular, the musical tradition of the Hephthalites. In order to understand the social, political, and economic dynamics of the musical culture of the Iranian peoples of the Sassanid and Hephthalite eras, therefore, we must research the books that were authored, copied, or translated during the Samanid period. The result must then be compared with our finds in archaeology, numismatics, and other such fields. One such source that demands our special attention is the

Tarikh-i Tabari of Abu Ali .In AD 963, commissioned by Abu Salih Mansur Ibn-i Nuh (AD 961-976), the Samanid wazir, Abu Ali Muhammad Ibn-i Muhammad Ibn-i Ubaidullah-i (d. 974), began the translation into Tajiki of the Arabic text of the Perso-Islamic scientist Imam Abu Ja'far Muhammad Ibn-i Ja'far Ibn-i Yazid-i al-Tabari (AD 829-923). Called the Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings), the work deals with world events from the beginnings to the year AD 915, i.e., to the middle of the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir (AD 908-932). 's work which covers the events until AD 824, i.e., until the death of Caliph al-Mu'tasim, is known as the Tarikh-i Tabari of Abu Ali Bal'ami.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the materials presented by are not sufficient for a comprehensive study of the musical traditions of the Iranian peoples at the beginning of the Middle Ages. Tabari's data is not original to him. Furthermore, many of the sources on Iranian musicians and dancers, used by in his work, have not survived. 's own insight, however, is of great significance for the study of the musical culture of the Iranians. 's work, like Tabari's, can serve us as an informed guide. Without such a guide it would be impossible to trace the contributions of the Iranian musical tradition in the Arabic sources. And we are speaking about works that, according to al-Dinavary (AD 828-889), formed the bulk of the knowledge of the savants of the reign of Caliph Umar al-Khattab (AD 634-644).

Compared to the scholars who followed, too, we find 's knowledge of the pre-Islamic musical culture to have been noteworthy.

All this has brought us to an examination of the contents of al-Tabari's work on the subject of the musical culture of the Iranians before the advent of Islam. After all, at a time when the culture of the Tajiks is being "revived," we should know what status it held during the early Islamic times and what light additional sources can shed on the subject. Some of what is outlined below will be a reiteration of facts, of course, but there is still some merit in the exercise. Although worth close scrutiny, 's views on the musical culture have not been studied before.Although Tarikh-i Tabari is redolent with information about the lifestyle and culture of pre-Islamic Iran, it is 's contribution to it, especially on the musical culture, that makes the work attractive. 's coverage of the musical culture at various courts is brief, of course, but when it comes to the court of Khusrau Parviz (AD 590-628), his views become focused and poignant. In fact, it is this kind of informative contribution by Bal'ami that has gained fame for al-Tabari's Tarikh.

According to Tabari, Khusrau Parviz was the most astute, brave, and insightful of the Sassanian monarchs. He was called Parviz (victorious) because he had gathered the most wealth and because he had excelled in Luck among his peers.

Recalling Khusrau Parviz's reign, writes, "Parviz had a treasure which he called 'Badavarda' (blown in by the wind). Originally, this was a treasure that was being sent by the Emperor of Rome to Ethiopia. It was carried on a thousand ships all filled with gold, precious stones, pearls, rubies, and silks. The ship [sic] was sunk in a storm but the cargo, brought to the shore by the wind, fell into the hands of Parviz and was called Ganj-i Badavarda... Furthermore, 12,000 maidens served at the court of Parviz as singers, dancers...and he had a unique musician called Borbad..."

Similarly, Parviz's wife, beautiful Shirin, had gathered dancers and singers like Borbad, Sarkash, and Khushazarvak around her to enhance her knowledge of the national music of Iran. The directorship of the activities of these performers, singers, composers, and clowns at Shirin's "White Pavilion" was entrusted to Borbad. It was also at this very juncture when Parviz was being entertained by the Great Borbad, that historical Tajikistan began its life under the Turkish Khaqan of the Hephthalites. The Hephthalite government, a superpower of that time, had created strong political and cultural ties with the countries of the world, especially with China. Records indicate that between AD 507 and 531, the Hephthalites sent 13 embassies to the court of the Toba-Vays. Among the members of the embassies there were musicians and performers as well.Under the rule of the Khaqan of the Turks, the historical regions of Varazrud-Takharistan and Sughd were consolidated into independent states. The views of Abu Ali and the other authors regarding the musical tradition of the peoples of Varazrud, Takharistan, and Sughd during the Middle Ages is as follows. Both regions of Takharistan and Sughd are the homeland of Borbad-i Marvazi. Unlike Iranshahr and Khurasan that formed a single government, Takharistan and Sughd were separate political entities. Takharistan consisted of the southern and central regions of present-day Tajikistan, the Surkhan-Darya region of Uzbekistan, and northern Afghanistan. And this vast region, according to the Chinese traveler, Siyun Tszan, was divided by national boundaries into twenty-seven nearly independent kingdoms. Like Takharistan, Sughd, too, had its own constituents, including two regions, five urban districts, and fourteen rural districts in the Zarafshan and Qashqa Darya Valleys.

In tandem with the development of the musical cultures of Iranshahr and Khurasan at the court of the Sassanians under the Great Borbad, in Takharistan and Sughd, too, similar efforts were underway for performance, voice, and research in aspects of musical culture. The situation of solo instrumentation and voice in the context of literature, philosophy, and ethics was improving and expanding. Indeed, according to various written sources and archaeological finds, among the Takhari and Sughdian musicians of the time, Borbad-i Marvazi's "seasonal" and "ritual" songs occupied a special position. Chinese and Perso-Islamic sources indicate that the Takharistanis and the Sughdians used small and large drums, various types of flutes (nai and qaranai), lute, and large and small tambourines, and dutar. N. B. Bentovich states that in their performances the Sughdians employed more than eighteen different instruments.

During the fifth to the eighth centuries, historical Takharistan and Sughd had a considerable musical culture. In spite of the silence of the Perso-Islamic sources about what had existed, Chinese sources and recent archaeological finds point to a high level of musical culture in Takharistan and Sughd. They also indicate that Sassanian Iran's musical culture was positively impacted by this eastern development. Of course a great deal of this activity between Takharistan/Sughd and eastern (China) and western (Roman) lands depended on increased trade among the peoples involved. The best musicians, performers, singers, and clowns accompanied the trades people, ambassadors, and visitors to those lands. Discoveries at ancient Panjkent, Afrasiyab, Varakhshah, Tal-i Barzu, Ajinnateppe, and Balalikteppe indicate the type of professionals that lived and performed in Sughd and Takharistan during the time of Borbad-i Marvazi. In fact, images of musicians playing different musical instruments have been discovered in Panjkent, Ajinnateppe, Balalikteppe, and in the ruins of Khatlan. In the ruins of Panjkent we encounter the image of a beautiful woman in a white dress. She wears a crown made of gold and golden rings.

Elsewhere we encounter four women, musicians and singers, playing various instruments and singing.Furthermore, in the palaces of the rulers of Khatlan, I. Ghulamova has discovered the pictures of two women one of whom is playing the ''ud and the other the ghizhzhak. In addition, in his search in Balalikteppe, L. I. Albaum has found the broken pieces of the body of a tar and the handle of a ghizhzhak. The evidence outlined above proves that the musical cultures of Takharistan and Sughd had been on a par with the musical cultures of Iran and Khurasan.Chinese sources-The History of the Sung Dynasty

(AD 581-618), The History of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), and The New History of the Tang Dynasty-contain a wealth of information about the Sughdian and Takhari singers, dancers, clowns, and the instruments they employed. The authors of the History of the Sung Dynasty, after much deliberation on the musical culture of the Sughdians write, "Our knowledge of Samarqand goes back to the time when Emperor Ja'in II(AD 561-577) married a girl from the northern villages and brought her here. Actors from those areas accompanied the new queen to our land. This occurrence brought the musical culture of the newcomers to the notice of the emperor. The "Tszidiyan-Nunkhechzhin"songs were favorites.Apparently, over the centuries, the music of

the west (Chinese view), from Sughd to Khurasan, had many supporters amongtheChinese, Tibetans,andIndians;.Thisattraction to western music was intensified even more during the Sung and Tang dynasties.I. Shafer, an Americanmusicologist, writes that whenever western regions were conquered by the Chinese, their music, too, was treated like a "slave." Music was expected to be delivered to the conqueror. At the court, the emperor's chosen individuals were assigned to special "bureaus." According to the annals of the Sung Dynasty as many as seven bureaus, including bureausforSamarqand;andBukhara,wereestablished.When discussing the music of Samarqand and Bukhara, mention is made of the flute, naqarah, lute, tambourine, wind instruments, as well as ten other instruments. In the Bukhara bureau twelve artists, and dancers, singers, and were at work. A realist observer of the scene states that the Chinese were jealous of the progress that the Takharistanis and the Sughdians had made. The attendants of the Emperor of China as well as the Emperor himself were entertained by Bukharan artists-flute players from Samarqand, surna players from Khutan, and Dancers from Chach.According to the information in Chinese chronicles presented by Shafer in his Shaftaluha-i Zarrin-i Samarqand, in AD 713, the ruler of Samarqand sent a number of dancers as gifts to the court of Siyan Tszun (AD 710-755). Similar gifts were sent by the governors of Kumid (AD 719), Kish, Samarqand (AD 727), and Maimurgh (AD 733). In addition to dancers, singers and musicians, too, were sent to China from Takharistan and Sughd.

Chinese sources include pictures of some of the Takhari dances like Gului, Khytenu, Chzhenzhi, and, especially, Khusyunu. According to these sources, there were two types of Takhari dances: quiet and agile. The quiet dance had smooth moves with which the dancer soothed the audiences. But the dance that the Chinese youth preferred was called "jumping." It was performed by Sughdian and Chachi performers. The young dancers wore vaskats, long hats and shoes and danced to the music of the surnai. The Chinese audiences also liked the "Chachi" dance performed by Sughdian girls wearing tasseled hats, embroidered dresses, gold or silver belts, and gold embroidered shoes. The music was played by the famous Sughdian artist, Kan-Kunlin.The most famous of the dances of the Sughdians was the "Whirlwind" or khusyunu. The dancer included several whirling moves in her initial act referred to as "the girl's whirlwind moves." According to Shafer, when performing this dance, "Sughdian girls, wearing red dresses, green capes, and red shoes danced their way from one side of the stage to the other, including flighty moves and jumps in the act. At the climax of the dance, the Sughdian dancers winked at the audience, increasing the impact of the dance. Often the dancer's moves were so fast that a poet had remarked, "Any increase in the jump would, like a piece of a cloud, hurl her into space." At the time the emperor, his wife Lady Yan, and Rakshan favored this dance. The emperor's wife had gone as far as learning this dance while Chinese poets composed many poems about it and about the beauty of the eyes of the Sughdian dancers.

Within

Takharistan;andSughd,too,likeinIranshahrand Khurasan, music continued its development. According to the annals of the Tang Dynasty, "On the eleventh month, the Sughdians, tambourine in hand, danced, asking for rain or warmth. In their happy mood, they sprinkled water on each other," or "The Sughdians in large numbers danced in the streets and sang."The foregoing was a brief look at the history of the development of the musical culture of pre-Islamic Sughdia and Takharistan as outlined in Tabari's History and in the annals of China. the analysis was not meant to be comprehensive. It is hoped that researchers will continue the effort thus started.

|

Iraj Gulsurkhi

(Iran) |

Music in the Shahname

Firdowsi enumerates many musical compositions in his Shahname among which surud, bazh, and taranah can be mentioned. This kind of music predates the Shahname by some seven centuries.

Surud is a type of music that does not have any religious connotations. It included, with certain variations, the music of the court, military music, music played at lower courts, and at the houses of nobility. The music played at court was referred to as khusravani. This khusravani, of course, was different from the type of music recognized by the same name, i.e., the music that still exists in the Humayun maqam and other maqams and the native form of which is found among the present-day Lurs, Kurds, and Azerbaijanis. Fortunately, the original form of this music is rendered in notes and can be reproduced. In recent times, however, surud has assumed an exclusively military use in marches. A number of khusravanis have survived from the time of Borbad and there may have been khusravanis by others, given the fact that Borbad composed his works exclusively for Khusrau Parviz. There are still singers in Luristan and Kurdistan who perform khusravanis. The themes of these compositions are centered exclusively on the lives of the kings. Recently, I recorded a khusravani called Khusrau and Shirin in Luristan. It is in the Luri dialect. And I should add that folk Shahname, i.e., the Shahname that has passed from generation to generation orally, is several times longer than Firdowsi's original. Thus, the composition of khusravani continues. There is even a khusravani about Karim Khan of the Zand Dynasty. The recitations are accompanied by kamancheh, often with nai-i duziyaneh or dunai, or

withthetambourine. Khusravanis abound in Azerbaijan, Aran, Armenia, and Georgia. Shah Isma'il, Kurughli, and others have khusravanis of their own.Bazh is used in the context of worship and as such is a kind of religious zamzamkhani. It encompasses the recitation of all the hymns of Zoroaster. Indeed the hymns began with zamzamkhani and, with audience participation, reached their climax. Examples of Yasna 47, prepared for chorus and a wonderful bazh copied from the Alvand stele of the time of Xerxes, are available.

Taranah belongs to the public at large. In Persian "tar" means "wet," but in this case it means "fresh." Taranah, therefore, is a musical piece that is constantly renewed. The word "reng" in Persian is a corruption of tarangeh or taranah. A different type of taranah is employed at the end of each maqam performance.

Lands in Which Persian Music Thrives

The Persian language, especially in its Dari form, brings a large body of people together. But this gathering is in no way comparable to the one that is brought together by Persian music. By Persian music, of course, we mean the shur, mahur, nahavand, dugah, chahargah, and the recitation of the Shahname with its special heroic rhythm. Persian music is recognized in Armenia, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Spain, Southern Europe, Bulgaria, Rumania, even in Austria. It has influenced the works of Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Mozart, Johannes Brahms, Dukhnani, Franz Liszt, Gadail, Bela Bartok, and Arkal. George Ansko uses Iranian melodies of the Humayun and Chakavak type in his First Rhapsody. The history of the influence of Persian music in Africa is outside the purview of this study. In this regard, suffice it to say that the Iranian musician, Zaryab, who was at the Abbasid court at Baghdad, traveled to Spain and, while there, set up a school of music and taught the fundamentals of Persian music. Zaryab's compositions are well-known in Spain. They were prepared for the guitar in 1993.

The Predecessors

In spite of the manipulation of the information on the role of Persian music on the music of the Abbasid court, it is evident that Persian music and the Pahlavi language have had their impact. Abu al-Faraj , quoting Ali Ibn-i Yahya on the fifth tar of barbat states the following, "A long discussion occurred between Ishaq, the son of Musa Musili and Ishaq, the son of Ibrahim Mus'ab. Musili asked, 'Did you hear what he asked me? He could not figure out a simple thing like that by himself. He must have learned this from the books of the predecessors. I am sure that they have translators and that such things are being translated for them. If you happen to come across such books, keep me in mind'."

The foregoing shows that during the reign of the early Abbasid Caliphs, thanks to Iranian wazirs and amirs, books on music were translated into Arabic. Even al-, documenting his sources, refers to them as the "predecessors." Neither Ibrahim, nor his son Ishaq Musili, has divulged the secret of their trade. Their secrecy and the secrecy of the other professionals at the courts of the Abbasids create a mushroom of the Arabic culture of that time-it has an attractive facade but lacks substance of its own. And even that would not have been possible without marginalizing the efforts of the custodians of the previous culture and without generalizing their contributions under the term "predecessors."

The Caliph al-Mansur's astronomer who preserved the Zoroastrian tenets and whose family is well-known and trustworthy had a grandson called Yahya (d. 932). In his work called al-Nagham, in several places, Yahya refers to "the assertions of the ancients on music," but he never explains who those ancients are. Historical Traditions of the Time of Rudaki

The time of the pioneer poet of the Iranian peoples, Rudaki (d. 941), coincides with Iranian civilization's epoch of scientific, literary, and cultural achievements. The greatest minds of the time converged in Bukhara, the focal point of the sciences, literary developments, and artistic innovations, where theoretical and practical aspects of the fine arts, including music, were studied and enhanced.

Arab and Perso-Tajik authors have written extensively on the art of music of the Rudaki era and have explained the major trends in composition, innovation, and instrumentation. Their contributions distinguish this era as the period of the revival of Iranian culture in the East.

Regarded as one of the mainstays of the culture, music is deeply rooted in the cultural traditions of ancient Iran, especially during the Sassanian era. The music of the Sassanians was not only original but was rich enough to nourish music geniuses like Borbad, Nakisa, Sarkab, Sarkash, Gisu Navagar, Azadvar-i Jangi, and others who specialized in music for the masses. The Arab invasion and the subsequent politics of marginalization of Iran put an end to this musical culture and postponed the recognition, development and appreciation of the instruments, voice, style, and performance for centuries; it halted research in the field. Many shining stars were sacrificed to the bigotry of the invading forces. Much of this literature perished. The rest was subsumed under Arab identity. It was not until the rule of the Samanids that Iranian culture reasserted itself.

Strictly speaking, the scientific and practical music of the Sassanian era is original in nature. There were, of course, influences from Greece, Babylon, Egypt, and India. It is, however, the essence of that music that was original to the Iranian lands. Furthermore, the Sassanians were eager to discover new grounds but, within that effort, too, they emphasized the Iranian roots of their music. In spite of their wild nature, the Arabs did not destroy that aspect of Iranian culture. On the contrary, the palaces of the caliphs of Islam were filled with the melodies produced by Iranian instruments played by Iranian peoples. In the long run, the free spirit of the adherents of this trend brought about the emergence of what came to be known as the "Shu'ubiyyah."

The rich traditions of voice and instrumentation of the Sassanian era eventually surfaced during the reign of the Samanids with a new style and a revived vigor. The directors and the teachers at the Samanid court drew on the Sassanian experience for inspiration. Following the Sassanian model, Samanid officials reestablished a new musical culture, a synthesis of poetry and music that affected performance, instruction, publication, and development of the arts in general. At this time, therefore, we observe an elevation in the status of professional musicians Instruction of music as a basic science, using encyclopedias as textbooks, became an established method. This new attraction to music also affected the status of the singers, composers, and rawis who frequently found themselves in key positions in the government and politics of the realm. Important decisions could no longer be made without the input of artists. Eventually, an office called "Khurram Bash" or "Director of Fine Arts" was established. In addition to the artists, this office also drew on the talents of a bevy of experienced consultants from other fields.

It should be added that until the time of the Samanids, the Iranians had to exercise a degree of secrecy in the performance of their cultural rites. The Samanid rulers were partial to music and, for the administration of their realm, imitated the Sassanians. In Baghdad, the Caliph al-Muqtadir attracted poets, musicians, and representatives of other aspects of the musical culture. All these artists At the Samanid court, the synthesis of poetry and music that had begun under the Sassanians continued and led to a series of innovations in the ancient art and in its enrichment. Alongside the musicians, at this time, we also find poets like Abu Hafs-i Sughdi (d. 902), Rudaki, and others whose works complemented the efforts of the musicians. Some even incorporated music in their poetic recitations.

The artists of this time included Abu al-Abbas Bakhtiyar (9th-10th century), Isa Barbati (d. 941), Abu Hafs-i Sughdi, Mahmud Rubabi (d. 932), Abulhassan Jamasara (d. 952), Ahmad Khunyagar (d. 972), and other scholars and experts. They conveyed the musical tradition of Borbad (586-636/38), Nakisa (549-623), Ramtin (547-620), and Gisu Navagar (589-640) in a new format. The Khusravani, Lakui, Uramani are various types of Pahlavi songs, known in post-Sassanian times as fahlaviyyat. In fact, composition of the fahlaviyyat initiated a new trend in the artistic life of the times, many composers presented their own fahlaviyyat.

Lakui or Laskavi is the name of a musical form. The name is derived from the name of a beautiful singing bird. The lyric for this music was of the panegyric type and its formation is attributed to Borbad. During the time of Rudaki, this form was used very frequently. Indeed, Rudaki's bu-i ju-i muliyan is composed with this form in mind. It should be emphasized that, during the Sassanian era, the poet and the musician were often the same person. For this reason, Borbad, Ramtin, Azadkar-i Jangi (586-622), Sarkash (568-625), Gisu Navagar, and others were respected; they were treated as talented poets of their time. This trend was continued by the Samanid artists and was developed to its full potential by Rudaki and his contemporaries.

The combination of voice and instrumental music emerged as taranak (tranik), Chama (Chikamak), sarvod (surud), pazhvazhak, etc. Taranah(tranik) or chama (chikamak) also is among the most developed and recognized forms of the time of Rudaki. Many researchers, including Tajiks, recognize Rudaki as the founder of the genre.

We must add that this type of music (i.e., taranah), form and content, took shape under the Sassanians and that it appeared in two types. The first type is related to Borbad and his time. He was the first, to create the calendar or seasonal taranahs. The other type of taranah was called "rustic" taranah (rustak tranik). The style and the manner of its performance belong to the villages. It is the texts of these songs that are identified as fahlaviyyat.

These two types, i.e., taranah and chama, are mentioned in Abu Nasr al-'s Kitab al-Kafi al-Musiqi as taraiq and ravashin. Furthermore, this kind of music was related to the professional classes of Bukhara, Sughd, and Khurasan who listened to that music to relax after a hard day's work. The music itself is produced on ancient instruments and is accompanied by chorus. In cities, this music assumed local color and special distinctive features. This type of music was distinguished as professional and dated back to Borbad and the other masters of the Sassanian era. Many ancient sources reveal that the Arabic metric system is rooted in this era of Persian music. The important point then is that the well-spring of Arabic music is the musical culture of the Sassanians.

The form and the structure of the lyrics of the Sassanian period are based on three distichs, the very form that is retained and appears in Rudaki's compositions. That is why we cannot claim Rudaki as the founder of the taranah. Nevertheless, the same musical, literary, and historical sources relate that the lyrical aspect of the taranah flourished at that time. Furthermore, this music exerted a great deal of influence on the musical culture that developed at the same time at the court of the Umayyid Caliphs. In fact, the great musicians at the Arabian courts, musicians like the Musilis, Nashit-i Fars, Shahda-i Fars, and others, were all Iranian. Indeed, musicians like Alavaih-i Sughdi, Khurram-i Samarqandi, Bashar-i Burd-i Takharistani, and others held high positions at the Abbasid court. They have not only attributed their knowledge of music to ancient Iran, but have cultivated that musical culture as well. There are many statements like the following: "The Arabs have not made any contributions to music; the music at the court of the caliphs is nothing but Iranian music."

Similarly, there is another form called khurasani which also flourished during the Samanid times. This form, which was performed for relaxation, was based on the speech of the common people, had a very complex performance feature, and used the saz for instrumentation. The structure of this music is explained by Abu Nasr al- who traces its history to the Sassanian times. During the Samanids, this genre is developed further and is called khurasanikhani. Many master musicians like Muhammad Khusravai or Khurasani (d. 951), Jangi-i Mudaknir (d. 961), Isa Barbati, and others are known to have worked with this genre. Explaining the art of khurasanikhani, Rudaki says:

Askarali Rajabov

(Tajikistan)

|

Another of the genres prevalent during the time of Rudaki was the sarvad, surud, chakamak which also had taken shape as a vocal form during the Sassanian era. This genre, too, rooted in the efforts of Borbad, Nakisa, Bamshad, Azadvar, Gisu Navagar, and others was formalized during the Samanid era.

Mavara'unnahri and Surud-i Parsi, too, belong to the time of Borbad and are fully developed at this time. Rudaki proves his mastery in this genre in his "Lament in Old Age":

|

Without a doubt, the musical culture of the time of Rudaki had been very varied, revealing the aesthetic diversity and the richness of the Sassanian court. The development of the musical culture of the Samanids was not limited to that dynasty. Classical music received special attention and schools of music were taught by experts like Abu al-Abbas Bakhtiyar. The scholars at the school researched the theoretical aspects of music discussed in the works of the ancient Greeks and devised new methodologies. Besides, not all the scholars followed this trend. Katibi-i Khwarazmi (910-980), Abu al-Abbas Sarakhsi (d. 930), Ahmad Sarakhsi (d. 899), Abu al-Vafa-i Buzjani (940-998), Abu Nasr al-, Ibn-i Sina (980-1037), and others chose to continue the traditions of their ancient ancestors. The scientific and practical musical school of the Samanids alongside research in the works of their Iranian predecessors made noteworthy contributions in the instruction and translation of the works of such Greek scholars as Plato, Aristoksin, Nikomakhus, Aristotle, Ptolomy, and others. The methods of analysis, especially the manner in which the Greeks related music to the movement of the spheres, was criticized and music study was found on a scientific basis.

Because of this bold step taken at that time the musical culture of the Samanids is devoid of cosmological and legendary connotations and explanations. The musical culture of this era is based on works like Traniknamak or the book of taranahs and on chapters from Andarz-i Khusrau Qubadan, and Khusrau Qubadan va Qulam-i Dana-i U, works that had survived the Arab invasion. By using these sources, the national spirit of the ancient music is recaptured. In addition, the music researchers of the time did not limit their understanding of music to the local sources. Rather they expanded their reach and incorporated much of the musical knowledge of the time into their original creations. This method of research was the hallmark of the contributors of the Rudaki era. The results of these innovations in scholarship appear in the works of Abu al-Abbas Sarakhsi, Ahmad Sarakhsi, Abu Nasr al-, Ibn-i Sina, Zaila-i Isfahani, and others.

The belief that the Samanid music scholars imitated the Greeks is patently false. The music of this era has an exclusively local color and feel. Al-'s introductory note to Kitab al-Musiqi al-Kabir addresses this issue. "The Pythagorean thought that relates the creation of music to the movement of heavenly bodies must be rejected. The roots of music are in our knowledge and what is outlined here is the result of the efforts of our ancestors in this field-it represents their perception, talent, and understanding of this art."

Another important aspect of the Rudaki era is the devotion of the researchers to the revival of the traditions of the ancients. They concentrated their efforts on the pre-Islamic music of Ma Wara' al-Nahr and Khurasan, abandoning the musical developments that had been heavily influenced by Arab thought. Instead, they grafted the traditions of the Sassanians and the Sughdians to the body of their own innovations and compositions. It is at this time that, in spite of the barbarism of the Arabs, Abu al-Abbas Sarakhsi, Ahmad Sarakhsi, Abu al-Abbas Bakhtiyar, and others gathered the remnants of the musical culture of the past and recorded it for posterity.

Another contribution of the scholars of this time was a scientific compilation of the vocal and instrumental terminology. Forms like Tarak (zakhmazani), santur, chaqanah, shahrud, zangalak (zang), vanchak (vin), nai, dora (daira), taburak, shaipur, zandvar, zir, bam, barbat, dastan, mushta, rubab, ghizhzhak, zamzama, chama (chikama), taranah (tranak), surud (sarvad), and others were injected into the body of the scientific and practical literature at this time.

Still other aspects investigated at this time are the aesthetic, spiritual, and finesse of music as well as its public appeal to both scientists and artists. And none of this investigation is based on Greek contributions. Rather, it is an investigation that concerns the very life of the contemporary peoples and of their ancestral legacy. Recognition and instruction of the contributions of Rudaki will, without a doubt, enhance our appreciation of our fine arts.

|

Mehdi Akhavan-Sales

(Iran) |

Our Music

(In Memory of Sadeq Hedayat)

Our music is deep and sublime, humane and innocent. Its world encompasses our joys and pleasures as much as our laments and sorrows. But more than everything our music is delicate. It imparts serenity to the soul and affects us in ways that cannot be described in words.

I really cannot hide my feelings for our music (fortunately, my westernization has not reached that point yet). The melody of the tar devastates me to no end, especially in bayat-i turk, or Humayun, or Abu Ata, or Shur, or sigah, or chargah, or bayat-i Isfahan, or afshari, or mahur, or any of the others. I derive a similar enjoyment from listening to the sitar, santur, and kamanche. Recently, I have begun to enjoy violin and piano performances as well. We also should not forget suzani. Its music is in our blood... is of us... is us.

There is a condition, however, for the appreciation of this music. The individual should live in Iran until the age of twenty or thirty. After that nothing can replace the impact of Persian music on him or her. And you will not be able to deny its impact. The question, however, is this. Do we have to deny this feeling? Modernization and progress demand that we deny that our traditional music thrills us. And, unfortunately, many conform. Snobbism affected us from when, in ancient times, we set eyes on Westerners. Until today, like leprosy, their acquaintance has been eating away at our lives.

* * *

Dr. Tafazzuli, a good sitar player, spoke to me about his meetings of a number of years prior to our conversation with Sadiq Hedayat, in Paris, "Hedayat Sadiq and I met occasionally," he said. "One day he happened to be near my house. We watched the people, walked, and talked until we reached my house. I invited him in and he accepted. Inside, we rested and talked about diverse subjects as distant as Ray and Rome and Baghdad. We also imbibed an "elixir" that I had brought some time ago from Europe. We then talked about music. I suggested playing a record or two on the record player. He did not react. I named several records asking for his input, he did not respond. I enumerated the best of the Western singers, he remained silent. He eventually rose and, holding his drink, walked to the cupboard. When he returned, he was carrying my sitar. I was astounded as he handed the sitar to me and sat down. I had heard that he was not fond of Persian music.

The sitar was tuned for [bayat] turk. I began playing, beginning with an overture leading to gushas and farazes. It was a special time in our lives. Our youth mingled with the drink and the song. He sat there, nodded quietly and murmured something. Moments later he brought me some sweetmeat, asked me to play afshari and returned to his place and sat down, waiting in silence.

I tuned the sitar and began, passing boldly each stage, getting further and further into the spirit of the music. Suddenly I heard cry. 'Stop, stop!' he said, and began to weep.

I put the instrument down and ran to him. He held me back with his hand and indicated that I should leave him alone. I did.

We returned to the food and the drink and the talk. I hoped that we would reach a stage where I could ask him about his reaction to the music. He read my thoughts. 'A lot is said about me and my negative attitude toward our music,' he said, 'but they are all lies. I can never deny the depth and the purity of this music. Never. It entrances me and plays havoc with my soul. It drives me to insanity. It drains my energy.'"

* * *

"'What were we talking about?' he asked rhetorically. 'We were talking about the spiritual depth of this music in our being. Yet often I feel this music to be bound, as if confined to four walls where its notes and melodies fail to mingle. I feel our music has the serenity of the mountain brooks and, thereby, lacks the tumultuous waves of the ocean. Furthermore, it is filled with agony and submission to the will of God rather than with determination, anger, and decisive action. It lacks warmth. It is the music of the enslaved; the music of those who have suffered and who have been humiliated. There is nothing in it about victory, bravery, and standing proud before history. Yet it is a simple music, especially for those who understand it. Whereas the works of Beethoven and Tschaikovsky require an urban taste, a complex mental readiness, and knowledge of the subject before they can be appreciated, our simple music can be enjoyed by the peasants and the shepherds without need for any special knowledge.

That is why when I listen to our music, I find it fit for the festivities of Khusrau Parviz. I see Khusrau seated comfortably and, as he is being fanned occasionally, reaches for a grape. Shirin, his beloved, sits across from him. The music fills the hall as Borbad enters and enchants them all. Here Shirin's complaint reaches Khusrau's ear and Khusrau's love for Shirin is reaffirmed. Our music fits this scene but, unfortunately, you and I do not entertain with festivities of that nature.

We do not derive the total joy that the gushas and navas afford for a reason. That reason is compelling enough to persuade us to cast a closer look at Western music and, where possible, adopt some of its features."

* * *

To date, I have not encountered any substantial improvisation and renewal of our musical heritage. There is, of course, "orchestration." But even that is done in a most unorthodox manner. Simultaneous playing of several instruments and mixing of several notes or bringing together of Iranian and European performers cannot mask our lack of originality. All this activity has ruined tasnif (i.e., music, lyric, and voice) at the public level. If any good compositions have resulted from these bold steps, I am not familiar with them. Nothing is published along these lines.

While our modernization in music leaves much to be desired, in the genres of poetry and prose we have made real inroads. Looking at the future indicators, it seems that there still might be some hope for our "fine arts." After all, no civilization has suffered as a result of correct adaptation of principles from another civilization. Furthermore, is not civilization a kind of transaction of cultural treasures?

| Khosrow Ja'farzada

(Iran) |

Contradictory Definitions Stunt the Growth of

Persian Music at the International Level

Unlike European music which enjoys the support of the church, Persian music, like an orphan child, has to fend for itself.

Persian music is the outgrowth of an oral tradition. We can thus echo some of our officials who believe Persian music to be "backward," i.e., it reveals little or no development or perfection. As a result these officials deny Persian music a place in the culture and art of contemporary Iran and deny that it meets the needs of present-day Iranian society.Of course, it should be noted that the attribution of backwardness is a temporal rather than a qualificative assessment of Persian music. European classical music, too, compared to contemporary European music, the staple of concerts and chamber music, is backward. Backwardness in the East, however, is a more all-encompassing phenomenon. It includes not only the art of music, but the whole culture, including the sciences and the social and political relations.

Ibn-i Khaldun's Cyclical View of Culture

A discussion of "backwardness" is outside the purview of this article. We can, however, distinguish a salient feature of it, discontinuity. This feature applies as much to the musical heritage as to the culture as a whole. In this circumstance our experiences have been cyclical as opposed to linear. Therefore, each experience is independent. This lack of continuity prevents the society from building on the knowledge of its past experiences. Each generation completes its cycle and leaves. The next generation begins a new cycle. This is not to mention the new generations' attempts at rooting out the vestiges of the decadent past.

In his thirteenth century work, in relation to Arabic and Islamic societies, Ibn-i Khaldun speaks about this very cultural cycle. He believes that cyclical movements strengthen religious beliefs and affect social stratification. These movements begin in the desert where God is the individual's major companion. Soul-searching brings the individual to a strong sense of tawhid and to the dictates of the Qur'an. Moving into the cities then, the sons of the desert take control only to fall victim to the onslaught of the amenities of urban life. The cycle begins anew.

A cursory look at the more recent history of Iran illustrates this point. The Qajar Dynasty displaced the Zand and destroyed all that that dynasty stood for. Rather than Shiraz, the Qajars ruled from their newly inaugurated Tehran. Several generations later, the Qajars fell victim to Reza Khan who set forth a program of modernization and westernization to catch up to the more advanced countries of the world.

Continuity in Persian Music

The continuity of Persian music stops with Westernization. The development that had begun with the efforts of Darvish Khan and Aref-composing valuable songs and concerts-also comes to an end. A hundred years passed before the Sheida and Aref groups attempted to recapture that moment of history. But their efforts, too, were interrupted by the current regime.

We must note here that the efforts of the 1960's and 1970's to recreate the situation during the 1880's and 1890's would not have been possible without the progressive technology of the West. Besides, the two periods were not totally isolated-Ustad had experienced both eras. Lack of Activity in

Documentation and Recording

Unfortunately little documentation and recording has been accomplished either within Iran or abroad. The only worthy contribution is Mahmud 's Radif-i Avazi-i Musiqi-i Sunnati-i Iran bi Ravayat-i Mahmud-i Karimi ba Avanavisi va Records produced of Iranian music at an international level are neither numerous nor representative of the present state of Persian music. Only Hassan 's nai has been successful and has gone into a second printing. There are also some records sold at the international level, including Faramarz 's works; Dariush 's tar; Muhammad 's nai, accompanied by Mahmud ; and Majid 's santur. There are, however, no publications dealing with the contributions of Muhammad Reza , Hussain , and Muhammad . Their works are produced on cheap cassettes for the Iranian market or for the entertainment of the Iranians abroad. In the European record stores, for every 40 or 50 Eastern records (Arabic, Hindi, Turkish), there are only two or three Iranian records. From among the recent productions, only the new composition of Hussain and Khusrau -Nau Bang-i Kuhan-is recorded on compact disc (CD) in English and sold at the international level.

Contradictory Definitions

of the Persian Musical Theory

Another difficulty in the way of introducing Persian music at an international level is a lack of credible sources for the study. Each composer (ustad) has his own interpretation. The chaotic information provided on the jackets of the Iranian records in English, French, and German is indicative of the difficulty of any student of music trying to learn the basics of Persian music.

The first theory for Persian music was written by Ali Naqi Vaziri. Following his understanding of European music, he based his study on notations. The notes that he proposed for Persian music, however, were not accurate, because Persian music lacks the harmonic quality of European music. Rather, it emphasizes the melodic function of the sound.

These five notes of Vaziri then created a controversy as a result of which musicians not familiar with the Iranian system labeled Persian music "unscientific". Even Ruhullah Khaliqi in his book states this fact. In the last chapter entitled Nazari bi Musiqi, he says: "European music follows a set of strict rules while our present music is devoid of rules; our music is not based on scientific principles and does not meet our present-day needs."

Scientific and Impractical Music

The difficulty with understanding Persian music stems from two things: the application of science to music and the manner in which Monsieur Lumier imposed European notes-do, re, mi fa, sol, la, si-to an analysis of Persian music. This was, of course, after Nasir al-Din Shah and Amir-i Kabir introduced "science" into the Dar al-Funun (circa. 1856).

Iran's musical heritage was lost under the Safavids. Thereafter, lacking rules and regulations, both in Iran and abroad, the Iranian musicians learned the rules for European music and applied them to their own music as if those were some kind of universal music rules.

At the present, there are two possibilities for a theory for Persian music and the two are not absolutely distinct. The first is related to mathematics and exact sciences (deductive theory). The other relates to the experimental sciences like physics and chemistry (inductive or empirical theory). Music uses both these theories. The 12-music of Arnold uses the deductive theory. The deductive school creates musical forms that had never existed before and, consequently, had not been subjected to experiments.

In relation to Persian music, we are talking about the inductive theory. To reach a theory here, we must study the radifs, etc. used by the past masters and arrive at an understanding, classification, and systematization of the elements involved.

Instruction Through the Oral Method

As long as no musical representation is available from the works of al- and Urmavi, it would be difficult to know to which theory they could have belonged. Mas'udiyyeh distinguishes 12 maqams. These maqams, which are attributed to Maraqa'i and which appear in the manuscripts of the Safavid era, do not correspond to the practical use of the music of that time. All this brings us to the main question: How do Iranian music teachers convey their knowledge to their students? The answer is in the same way that a mother teaches her language to her young, through imitation. Neither the mother nor the child is familiar with the theory of language. Similarly, Iranian teachers of music do not know the intricacies of Persian music beyond the names of the maqams and dastgahs.

Is Theory Necessary?

Concerts of Persian music are gradually being incorporated into the body of world music. Foreign musicians, therefore, will need access to the knowledge that the teacher conveys to his student. The foreign musician, however, does not have the luxury of living at the side of an ustad for a considerable period of time to learn the intricacies of the music. For Iranian music to thrive at an international level, therefore, it is imperative to not only devise a theory for it but to facilitate its documentation and instruction as well.

Music

Without a doubt, the end of the 20th century will be recognized as a historical era for European-style music. During this period, alongside the regularities, some irregularities happened as well. These irregularities were not confined to the United States and Europe but included other nations, including the recently-formed independent republics of the former Soviet Union. What is peculiar about this era is that it imposed the varied music of the West on the traditional music of the Eastern peoples. The outcome of this imposition was often disastrous.

During the 70 years of Soviet rule, an unrealistic and unwise policy was in place. This policy injected a heavy dose of communist ideology into the works of the Central Asian musicians. As a result of this imposed ideology all aspects of the creative process, including composition, were affected. The composer became the executor of orders from above; he composed only pieces that were needed by the regime and which were ordered by the Communist Party. It is sad to say that the musician, rather than as a free person, had become a lackey of the Party functionaries. Many musicians turned their back on our national/traditional musical culture, and, insolently, humiliated it and its supporters. The regime justified this kind of neglect of the heritage of the masters of instrumentation and voice by associating it with the actions of detested feudalist states-something alien to the progressive Soviet mind.

What was the civilization that the Soviets so forcefully suppressed? It was the result of the untiring efforts of great Central Asians like Borbad (6th and 7th centuries), Ibn-i Suraij (d. 743), Abu Abdullah (858-941), Abu Nasr al- (873-950), and others. Is this not an astounding phenomenon in the history of world civilization? Besides, the contributions of these great men were not confined to a specific area. They participated in the formation of regions and nations by promoting instrumentation, voice, and lyrics.

A survey of the literature on music and the musicians of the past centuries yields the following points: 1 - The monody music has grown alongside the Islamic religion and, over centuries of development, has influenced the thoughts of millions of people.

2 - The essence and the various interpretations of musical compositions are unique and unrepeatable phenomena. These phenomena encompass fine but substantial points regarding the rhythmic and melodic quality of the music.

3 - During the 70 years of Soviet domination, under the guise of "realist socialism," terms like compositor and melodik (musician), were imposed on the Central Asian artists. Today these appellations should be replaced by akin in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, ashiq in Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey. In Tajikistan and Uzbekistan they should be referred to as bastakar.

4 - Furthermore, like in other progressive countries, the monody artists should be identified with their contribution and should be duly rewarded.

5 - The phenomena outlined above have the same special scientific and practical values as their creators. These distinctions, to a degree, had been included in the maqams and used as criteria for differentiating among the styles and modes of musical compositions.

Among the compositions at our disposal, there are certain songs the creators of which are unknown. What is the spiritual impact and the meaning of these monody pieces? The answer to this question can be equally easy and difficult. The difficulty lies in that the vocal aspects of these pieces are unknown; the establishment of their tonality and melody is also difficult. The artist performing the piece is not sure how to end what he has started. Finally, he finishes it by improvisation. In other words, the composer of this monody composition does not follow any particular set of rules.

Let us illustrate the above statement with specific examples. The peculiarities of the creation of bayaz music appear in Tajiki, Turkish, and Arabic texts of the 9th to the 19th centuries. These texts explain not only the geographic domain and the compositional complexity of the piece, they also explain the time of the performance of the piece. More specifically, one of the famous melodies is called "chargah." Its composer is Pahlavan Muhammad who lived in the 15th century. The piece is based on Mawlana 's and begins with the following bayts:

This extremely pleasant song is composed in honor of the Great Mir Tirmidhi. Every musician in Khurasan, especially in Samarqand and the Iraq of Ajam, had heard this piece. Indeed, it remains indelibly etched in the memories of the people.

There is no doubt that the account presented above is sufficient for identifying the work and its author. If we pay closer attention to Alisher 's description (his teacher is Ustad Khwajah Yusif ), the impact of this music on, and its value for, the people of its society will become evident. The important thing is that Pahlavan's work covers a large geographical area.

It is not difficult to identify the characteristics of Muhammad Pahlavan's work, using Nava'i. The work appears in different forms in other musical compositions and utilizes the required poetic and chahardah-zarbi principles. A comparison of the many texts of this form in present-day musical compositions proves this point. These texts include: chargah; one of the shu'bas of maqam, zagulah (12 maqams in all); the instrumental shu'ba of Mukhammas chargah; vocal shu'bas of talqin chargah; nasr-i chargah; ufar-i chargah; and, finally, the five types of savt-i chargah and maqam-i dugah in shashmaqam. It may even include, theoretically at least, talqin-i savt-i chargah, which is the initial part of the quintet mentioned above (see advar, etc.).

Using the same method, we can identify another musical work Our investigation began with the ghazal of Nava'i (the incomplete text). During the Soviet era, a considerable portion of Uzbek musical works were either damaged or forgotten. The old songs that persisted were subject to the whim of contemporary poets. This included the organization of the Bukhari, Khwarazmi, and Ferghani maqams. Among the works that have survived, we can mention: mustazad (name of a poetic meter) and in shashmaqam (the buzruk maqam), mustazad ruk, qashqarcha-i ruk, saqinama-i ruk, ufar-i ruk, and Siyavosh-i ruk. There is also the nava maqam, including mustazad-i nava. Saqinama-i mustazad-i nava, and As a result of the comparison of a number of maqam compositions and related mustazad forms we come to the conclusion that poetry of the contemporary Khwarazmian poet, Chakiri (Muhammad Yusif Kharrat [1889-1952]), fits Nava'i's compositions best. This should have been stated a long time ago that Chakiri knew the poetry of Nava'i well and that he based many of his lyrics on the traditional music or performed the traditional compositions according to his own personal style. He has composed many works using Nava'i's work. The proof of this, of course, more than anywhere, is in the heroes of Chakiri-they resemble the heroes of Nava'i very closely.

Herewith, therefore, we state that the composer of the chargah melody is Khaja Abdullah . Our statement is supported by other composers, including Muhammad Ali Fattah Khan, Jurabek , young singers Irkin , and Mashrab .

Research in the various facets of music, especially in the processes whereby unknown pieces are composed, is of great value. We must use the knowledge stored in our manuscript collections, compare the data therein with current usage, and identify some of the unknown and less known musical compositions.

The Image of Funerary Dances on Sughdian Ossuraries

In Tajiki, the word "tanbar" is understood as astudan, ostokhandan, or assuar (ossuary). In general, the Sughdians, Khwarazmians and, perhaps, Aryans of the East have used the word in this sense. The word "tanbar" is written on an ossuary found in Khwarazm in a place known as Taq Qal'a. Many different tanbars have been discovered in Khwarazm, Sughdia, Istarafshan, Chach, Ferghana, Takharistan, and Merv. They are a valuable source for understanding the customs, traditions, and the history of the Perso-Tajik peoples. Using the information provided by the tanbars over the last hundred years, researchers have provided ample explanation for many aspects of the religious life of the Sughdians. But there still remain many other complex and obscure aspects to be explored. Our concern here is focused on the funerary dances depicted on tanbars discovered in Kish in Sughdia. As a result of the excavations, in 1965, in the village of Uzqishlaq of the rustic district of Yakabulaq of the Qashqa Darya region of the Republic of Uzbekistan,

The first picture depicts a tall woman in a long-sleeved, long robe which reaches her ankles. The same type of robe and belt is worn by the other participants as well. The robes have vertical black and white stripes. This customary mourning robe resembles the dark mourning clothes of present-day Zarafshan, Istarafshan, and Ferghana regions.

According to ethnographic studies, in the wake of a Tajik man, a black or dark robe, a Tajik hat (tupi), and a sash is worn. Among the Tajiks of Bukhara and Samarqand a special mourning attire of black and white or jet black is preferred. Furthermore, according to Aziza Mardanova, from Bukhara, in their funerals, the Iranians of Bukhara wear black and white knit clothing. If what Aziza Mardanova states is correct, then the Sughdians, too, might have worn knit black and white robes. Urban women, including those of Samarqand and Bukhara, have a dress called Munisak, which they wear in funerals and during the mourning period.

Similarly, the participants in the ceremonies wear mourning clothes. The dancer has a kerchief in her hand and, lifting and placing her right leg on the left, is dancing. The second dancer, like the first, is without head cover and has long hair. She is lifting her right arm and moving the left towards her waist. She is dancing on the tip of her toes. The third dancer, like the other two, is tall, bare headed, and has her hair in two long braids. She has a wreath in her right hand, is lifting her left leg while dancing on the toes of the right foot. From the bare legs of the dancers, it seems that they are wearing only the robes. The first two dancers in the picture have handkerchiefs in their hands.

The man, located between the second woman and third, is bare headed, and is playing the 'ud. The dancers are bare footed and the dance is a special mourning dance.

G. I. Dresvianskaya, G. I. is mostly correct in her statement that the picture described above resembles the mourning customs of Zarafshan of Sughdia and that women mu'bads participate in the ceremonies. Furthermore, the ceremony depicted on the tanbar is taking place during the Nau Ruz. It is a family ceremony and is taking place at a family grave site. According to the sources at this time, the Zoroastrians of Sughd, Khwarazm, and other regions of Central Asia celebrated the memorial days of their Farahvashis. About this Abu Raihan al- says the following in his Asar al-Baqiyah:

At the end of the month of Khushum, the Sughdians cry for their dead ancestors, lament for them, scratch their faces, and bring them food and wine. The Iranians still follow this custom of their ancestors.

The picture depicted on the tanbar is not different in any way. The mourning ceremony for the benefit of the soul of the deceased ancestors is performed by the living in the graveyard. They are performing the rites wearing special mourning clothes.

According to the recent anthropological analyses, today, too, some of the relatives of the deceased in Tajikistan lament for him while some near relatives dance. The anthropologist Aziza Mardanova writes that in some regions of Hissar, Shahr-i Sabz, and Qarataq these dances are known as sadr or sama'. These customs have been observed in the villages of Ab-i Garm, Qala Nav, Yafraq of Ramit, Qarakamar of Kutash, and in Shatrut of Khufar, and Sari Asiya in Uzbekistan. All those dances are performed in accompaniment of daira and rubab instruments and are, in the main, very similar to each other.

Anthropologists have recorded the Heydariqa song in many of the villages of Western Pamir, Darvaz, Shurabad, Dasht-i Jum, Sar-i Mourning songs and dances have survived among the Tajiks in the Qashqa Darya region where the tanbars were found. Other archaeological finds, too, confirm that Bukhara is ancient. According to the Shahname of Firdowsi, Siyavoshgird isin theregionofHindandSind.AfrasiyabbringsSiyavosh somewhere else and kills him. In any event, Siyavosh's unjust death at the hand of Afrasiyab was well-known among the Sughdians who, every Nau Ruz, held a mourning celebration in his honor.

The other tanbar that I would like to discuss was given to the students of the village of Darkhan (Yakkabag region) in 1984. Later on it was passed on to the students of Tashkent University. The tanbar is in the shape of a ceramic box (47 cm length, 34 cm width, and 22 cm height). The tanbar is made to resemble a building with a verandah and a dome. The support for the archway of the verandah is held in place by a young man. The youth is supported, in turn, by his right knee and his up-lifted left foot. He is wearing a short tunic and a pair of short trousers. He also carries a kerchief in his hand. The clothes of the youth seem to be made of leather. A strong individual, he wears a hat and earrings. The archways are decorated with depictions of the moon. The space in between the arches is decorated with ivies. In the first archway there is a picture of a man. A woman is depicted in the second archway. The bodies of the man and the woman occupy all the space in the archways.

The first picture depicts a four-armed goddess. She is sitting on a mancha, lifting her right leg, knee high, over her other leg which is dangling. The goddess has a round, chubby face, thick lips, large eyes, and long eyebrows. She wears a diadem and on top of that, a fine shawl that reaches her hands. On her neck, she wears a necklace of pearls or shells and she has earrings in her ears. She is also wearing a short dress and a skirt that reaches her ankles. Around her head is a circle representing her divine descent. In the first right hand of the goddess is a small ax over which is a bird with a long tail and bill-like claws. In her second right hand, she holds a circle that symbolizes the sun. In her first left hand, she holds a pounding instrument, a mortar, and in her second left hand she has a few-days-old moon. In front of the goddess, two men, one with a surnai and another with a double-sided tabla play their music. We must add that the connector between the two tablaks is unusually long and decorated. The other feature of the tablak is that it is dented on one side.

The man sitting underneath the second archway has the same leg posture as the goddess. With his first two hands he is playing an instrument, perhaps a tar. In his second right hand he has a circle and bird ensemble similar to the goddess. In his second left hand he carries a daira over which the picture of a horse is rendered. The god wears a knee-length armor, shoes, and a hat with indentations resembling animal ears. Underneath the helmet, he wears more armor.

The man's armor bespeaks the military nature of his occupation. The 'ud player is sitting on the left side of the deity. Uzbek researchers, Z. Usmanova and S. Dunia, have studied this tanbar and concluded that the four armed deities indicate Hindu influence in Sughdian society. The many arms and the symbols they carry, they say, represent the functions which each god performed. They also believe that the god and goddesses are depicted dancing. Their dance, like the dance of Shiva, represents the everlasting nature of the world. The dance of the gods, therefore, has two meanings: the movement of the planets and the world of the deceased.

The image of a four-armed goddess riding a dragon also appears in the wall paintings of Panjkent. Researchers identify the goddess riding a dragon to be the keeper of the destructions of the water world.

On the walls of the palaces of ancient Istarafshan, too, there are depictions of goddesses riding lions. In one of the paintings, in one of her hands the goddess holds an ax with a bird and in her other hand she holds a dragon-looking object. Her two other hands have not survived.

The picture of the second four-armed goddess is better preserved. In two of her hands, she holds the representations of the sun and the moon. In her other hand she holds a scepter and, in her fourth hand, except for the shahlik, the other fingers are closed in a fist, indicating some mystery.