|

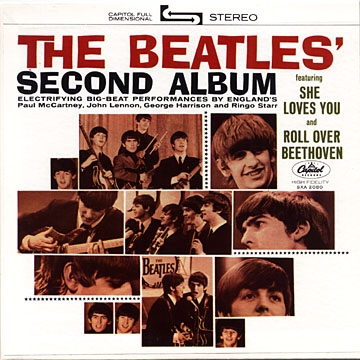

Every album has at least one amusing story attached to it. "Where It's At With The Wind" had enough to fill a career of twenty-five subsequent boring releases. Maybe that's why we never got past the third record. The three original members, Steve Katz, Steve Burdick, and myself lived a very isolated existence in the tropical backwater trench that was then Miami Beach. Having met in high school, we shared a love of the Beatles and All Things Sixties. The extreme heat has a tendency to breed a fanaticism of one kind or another and ours was the British Invasion. After prolonged research the three of us had come to the conclusion that western civilization, as we know it had peaked with the Beatles' Second album (American version) and was now in a perilous decline. In truth, we were musical connoisseurs with very wide tastes, but all roads kept pointing back to the Beatles' Second album. The Wind's early sound was based on this record.

At the time, we would practice several nights a week in Steve Katz's room in his parents home and work on five or six new songs a week. Steve & I were writing like crazy and in two years we had almost two hundred songs. To say that we were obsessed would be beside the point. The Wind was all we cared about. Unfortunately, the music scene in Miami at the time was still one of a particularly punky persuasion. Bad dye jobs, heroin addiction, and poverty seemed to be some of the necessary pre-requisites in gaining a foothold in the local scene. But by some dint of fortune, we did gain a Wednesday night slot at Finder's Lounge, a dilapidated club on Collins Avenue, down at the beach. There, we would play to two or three drunks and talk in the parking lot between sets about how we would transform popular culture within the next six to eight months. We did sense at the time that this would be an uphill struggle. It became apparent that we would live & die there in the heat if we didn't make some attempt to gain attention. Back then, it was actually still a fairly novel idea to put out your own record. This seemed like the only way out of our desperate situation. After making some calls (home), we were able to raise $1,600. We then took out the Miami yellow pages and started to look for a studio to record in. We first ended up at a small studio with an engineer/owner who I was reminded of many years later when they caught the Unabomber. We went into his studio with Shirley Bassey's recording of "Goldfinger" and told him that was what we wanted our record to sound like, notwithstanding the fact that we were a three piece rock band and this was a forty piece orchestra. This was merely a ploy on our part. We, of course, were shooting for the elusive mojo of the aforementioned Beatles record, but "Goldfinger" had a huge sound that we were also after. Besides, everyone understood the Beatles. It took someone with pretty refined tastes to get "Goldfinger", especially in 1981. The Unabomber nodded knowingly as he rolled a fat joint on the recording desk. But unlike his joint-twisting facility (or bomb-making), his skills in the studio were abysmal. We did a recording of "What's The Fun" which, thankfully, has been lost. After more searching, we finally found a place that would cut us a package deal: 14 songs for the $2,000. Sounded great, what the hell did we know? To us this was a major budget. The studio, Miami Sound, was located in the heart of the then burgeoning "little Havana" district of Miami Beach. It's proprietor, Carlos Granados, was in his forties and had already had a failed career as a singer, Chuckie Day. He now recorded Salsa bands in this little studio, day in and day out. There was some sort of mention of a silent partner who owned the studio equipment, equipment that I wouldn't learn the true value of for years later. Without getting too technical, Miami Sound had what are today considered some of the most coveted pieces of vintage studio gear: a Neve recording console, a full array of Pultec equalizers, two Pultec compressors (more on this later), Neumann tube microphones, and a MCI JH-16 tape machine, a fat sounding temperamental monster. We were told it was the same machine they recorded "I Shot The Sheriff On", which seemed plausible because Eric Clapton always recorded at Criteria Studios, Miami's premier recording complex. At our first meeting, Carlos seemed like an affable father-like figure. His enthusiasm, which would later manifest itself intermittently with bouts of moodiness and anger, was in full swing. Here was the man who was to help us steer popular music back onto its true and natural course. He, too, nodded approvingly as "Goldfinger" blared out of the huge red Urei monitors that hung from the walls. He got Goldfinger. Carlos was the man. We handed over the cash and we were ready to rock. Basic tracks went smoothly enough. We miked up everything and ran through the fourteen songs in the order they appear on the record. Mixing, though, was a problem. Early attempts did not meet our standards. The mixes sounded weak and tinny. We were crestfallen. Why didn't our baby have the same wild excitement as the Beatles 2nd album? Steve Burdick, our erstwhile drummer, came up with the answer as he put one of Carlos' lousy mixes through an old Superscope cassette deck with a built in limiter. The tracks perked up considerably. "Compression", he said. "We are missing compression". We went back to Carlos and told him how we wanted to mix the record: We wanted to throw the entire mix through a compressor. He looked at us like we were insane. We also told him we wanted a natural sound on all the tracks with no equalization on anything. First he started to laugh. Then he made a face and said, "Yea, sure. Whatever you guys want, heh, heh.". He was totally sick of us at this point. We put up the tracks and ran the whole mix through an old green tube compressor. The results were amazing. Drummer Steve was right. The record had a totally wild sound. Even Carlos was blown away. After we were finished (we mixed the entire record in one night) I remember him cradling the master tape and making believe he was accepting a Grammy award: "I just want to say one thing to everyone out there: FUCK YOU!". Right on, Carlos. Mastering and pressing proved just as harrowing and enriched with bitter life-learning type experiences. The first run of discs came out with the hole slightly off-center which made for a sea-sick listening experience. This was also accompanied by the presence of little bumps on the vinyl, which were apparent under close examination. The receptionist at the Spanish record pressing plant assured us that all the records passed the "white glove test". She escorted us into the back of the stiflingly hot shack where the records were packaged and, sure enough, there was a lady with a white glove on her left hand giving a final stamp of approval to all the records before they went into their cartons. When we mentioned the little bumps she re-assured us that "the little bumps were on all the records". We took our master to Criteria studios and had the whole thing re-mastered and re-pressed. After all was done and we had cartons stacked up in Steve Katz's room we wondered "Now what?" Because I had family in New York, I volunteered to take records up north and pass them around to "important people". I bought a plane ticket and came up with 20 copies of "Where It's At With The Wind". When I came to the Big Apple I went to all the record companies and Important magazines and dropped off records. In a story that is legend amongst our tight circle of friends & family, I went to the building that was home to Rolling Stone and got in the elevator. A bearded gentleman asked me what I was carrying. I proudly told him that this was my record and that I was bringing it up to Rolling Stone. He introduced himself as Kurt Loder, a writer for the paper (this was way before any of you knew who he was). He asked for a copy and I gave him one along with the phone number of where I was staying in NY. I went back down to the lobby without leaving the elevator. When I got back to my Mom's apartment she mentioned that someone named Kurt called and wanted me to call him back immediately. When I called the number his secretary, Susannah, said that I should come back to Rolling Stone NOW. I hung up the phone, ran downstairs and hailed a cab back to Rolling Stone. I was escorted to Kurt's office. He was playing our little record and said that this was the best thing he had heard in ages. He wanted to write a story about us. He interviewed me. What can I say? I was in shock. The next few months are a blur. I went back to Florida. The guys couldn't believe this was happening. A photographer was duly dispatched to Miami to take pictures of us on South Beach. The story was to appear in the October issue. When the Rolling stone piece finally came out, we got mail from all over the world. Every major record company wanted to hear us. We decided to move up to New York. My father found us a small house to rent. The night we drove up to New York we saw Let's Active at the Danceteria and met Mitch Easter, someone I had been corresponding with. I had been up for two days. Backstage, Mitch had sneakers that had ¼" magnetic tape for shoelaces. We introduced ourselves and made tentative plans to record together. Things were moving very quickly. We were riding the crest of a wave. We started to showcase at all the hot clubs. A plethora of bigwigs came to see us but nobody offered us a deal. We decided the only thing to do was make another record and quick, something more contemporary sounding. I was convinced that Mitch Easter was the man to produce our next recordings. I thought all his records sounded totally distinctive and I was enamored of his style. After scheduling difficulties were ironed out, the three of us drove down to North Carolina to record "Guest Of The Staphs". The record was done in three days: one for basic tracks, one for overdubs, and one for mixing. Mitch was the opposite of Carlos. He had very definite ideas about how to make records and he knew all about compression. He had infinite patience with us. I remember using about twenty six of his guitars and about ten of his amplifiers. I was happier than a pig in shit. In the end, some people loved "Guest of the Staphs", some were less than enthused. I think it 's a very different sounding record and I'm sorry we didn't have more time and money to pursue this collaboration. At this point the story becomes diffused. Though "Guest" got some great reviews and "House on Fire" became a modest college radio hit, the wave broke and the Wind never hit the jackpot. Rock bands are very fragile organisms. If success doesn't come at some point, very often the organism turns in on itself like a cancer and eats away at its very essence. This is what happened to us. We went through our bitterness, with Drummer Steve winding up back in Florida. We soldiered on but the original British-Invasion-meets-Motown was lost. Now, 20 years hence, we all have a multitude of projects (solo albums, outside productions, dance records, TV and theater works, etc.) under our belts. But the big wheel has spun around yet one more time. Steve Katz (now Barry, due to a threatened lawsuit: another story too long to go into here) and I are recording again as Tan Sleeve. Steve Burdick has been forwarding us drum tracks to work on. I don't know if you can call it the Wind and that's OK. It sounds real good. If the world doesn't come a-knockin', that's fine. We' re still at it and having a ball. We're lucky and blessed. This CD contains our first flush of youth with all our hopes and dreams embedded within. To us then, anything was possible and in a way, it still is. And if that ain't the whole damn point, I'll melt down my copy of "The Beatles' Second Album." Listen & enjoy the ride.

–Lane Steinberg |

| <-- B A C K |

|