This article introduces

the most humble of the semiconductor devices – the Diode. Its

predecessor was the Thermionic vacuum tube diode, widely used for

high voltage AC to DC power supply rectification and small signal

radio frequency signal detection, typically required in early

valve AM and FM broadcast radios. The solid state diode was seen

in those early days as a panacea for energy wasteful “heated

cathode emitters”, and although the introduction of inert gases

into “mercury vapour rectifiers”, offset, to some extent, the

high voltage drop losses of vacuum tube diodes, the march for

solid state continued. This article parades the victory of the

semiconductor diode, which today surmounts most, if not all posts

once held by the vacuum or its gas filled cousins. Its many

variants are introduced, and their new applications and associated

electronic behaviours are described, especially for RF usage.

|

|

Document

Summary of Contents

|

|

CONFIDENTIAL

This document is not to be

copied, transferred electronically or otherwise without prior

written consent from the Author.

DISTRIBUTION

This document may only

be shown to others with the Author’s prior consent.

|

|

1 Table

of Contents........................................................................

2

2

Preface To Semiconductor Diodes

...............................................

4

...............................................

4

2.1

General Comments On The Subject Of Semiconductor Diodes.....................................................

4

2.2

What This Document Contains.......................................................................................................................

4

3

A Short History Of Semiconductor Diode Devices...............................

6

3.1

A Perspective On Semiconductor Technology Progress...................................................................

6

3.2

Recollections Of Much Earlier Semiconductor Devices..................................................................

6

3.2.1

A Short Diversion Into “Coherer” Radio Telephony Receiver Technology.................................

6

3.2.2

The “Copper Oxide Rectifier” For Low Cost Battery Charger Application................................

7

3.2.3

The “Selenium Rectifier” For High Voltage High Efficiency AC to DC

Rectification

and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications............................................................................................................................................

8

and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications............................................................................................................................................

8

3.2.4

The Point Contact Germanium Diode Designed For Small Signal Radio

Frequency (AM) Detection

9

9

4

Modern Semiconductor Junction Diode Construction And Applications

10

4.1

General Semiconductor Junction Diode Types...................................................................................

10

4.1.1

Germanium Junction Diode Construction...............................................................................................

10

4.1.2

Silicon Junction Diode Types....................................................................................................................

10

4.2

Silicon Diodes For Radio Frequency Applications..........................................................................

14

4.2.1

Schottky Diode Construction.....................................................................................................................

14

4.2.2

Varicap Diode Construction........................................................................................................................

14

4.2.3

PIN Diode Construction...............................................................................................................................

15

4.2.4

Zener and Avalanche Diode Construction.............................................................................................

15

4.2.5

Photodiode Construction..............................................................................................................................

15

4.2.6

Solar Cell Construction................................................................................................................................

15

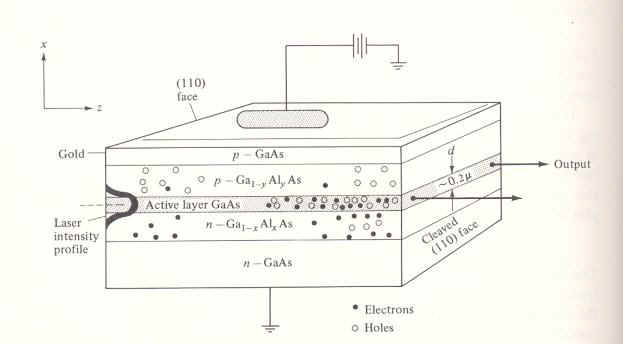

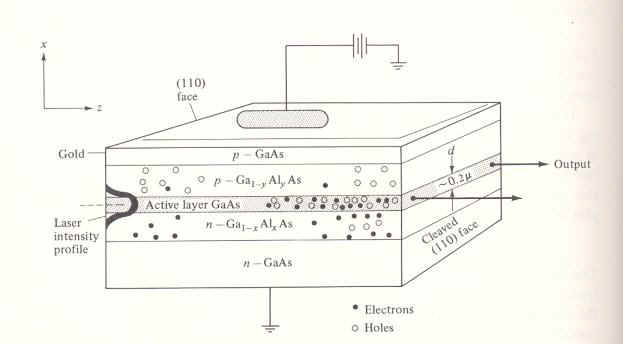

4.2.7

Light Emitting Diode Construction............................................................................................................

15

5

Electrical Properties Of Semiconductor Junction Diodes...................

17

5.1

Description Of Terminology..........................................................................................................................

17

5.2

Semiconductor Junction Diode Static DC Characteristics.......................................................

17

5.2.1

Semiconductor Junction Diode Forward and Reverse DC Characteristics..............................

17

5.2.2

DC Imperfections In Real Junction Diodes.........................................................................................

19

5.3

PN Junction Diode Reverse Breakdown Modes...................................................................................

20

5.3.1

Avalanche Diode Voltage Regulation......................................................................................................

20

5.3.2

Zener Diode Voltage Regulation...............................................................................................................

21

5.4

Junction Diode Temperature Dependence...............................................................................................

21

5.5

The Dynamic Characteristics Of Semiconductor Junction Diodes.......................................

22

5.5.1

Dynamic Impedance Of Forward Biased Diode.................................................................................

22

5.6

The RF Characteristics Of PN Junction Diodes.................................................................................

25

5.6.1

Forward Biased Capacitance.....................................................................................................................

25

5.6.1.1

Diode Series Resistance.............................................................................................................................

25

Composite

Junction Diode Model..............................................................................................................................

25

5.6.2

PN Junction Diode Reverse Biased Capacitance...............................................................................

26

6

Appendix....................................................................................

27

6.1

Transistor reference.........................................................................................................................................

27

6.1.1

The Point Contact Germanium Transistor.............................................................................................

27

6.2

Subject 2....................................................................................................................................................................

28

This

document opens with a short history on diode applications in general, beginning

with the primitive “almost a diode” Coherer detector used for Morse Code

reception and rusty copper oxide AC-DC rectifiers. Better semiconductor

materials such as Selenium were soon discovered, leading to higher voltage AC to

DC power rectification and low frequency audio signal application. RF signal

applications began around the time of the “point contact signal diode”,

which had sufficiently low capacitance to allow signal detection up to several

hundred MHz. Germanium gained an early status due to its ease of manufacture and

today Silicon reigns. Much interest is also shown in Carbon (diamond) and

compound semiconductor materials such as Gallium Arsenide, Silicon Germanium,

Indium Gallium Phosphorous, etc.

Various

Diode families are then described in applications that go far beyond those

simple rectification tasks they first gained footholds in. Today various diode

versions are used for voltage regulation

, dual polarity transient energy suppression

, dual polarity transient energy suppression

and electronically tuned filters

and electronically tuned filters

found in AM and FM car radios and

TV sets. They are used in microwave applications that require electronic control

of signal amplitude and also provide protection against high amplitude signal

microwave signal pulses. Photo detection diodes

found in AM and FM car radios and

TV sets. They are used in microwave applications that require electronic control

of signal amplitude and also provide protection against high amplitude signal

microwave signal pulses. Photo detection diodes

are available for infrared energy

and light, and can even be used for optical wavelength conversion when combined

with a Laser Local Oscillator source. Optically “pure” Laser Light Emitting

Diodes (LED’s)

are available for infrared energy

and light, and can even be used for optical wavelength conversion when combined

with a Laser Local Oscillator source. Optically “pure” Laser Light Emitting

Diodes (LED’s)

are used in every CD player and

their less optically coherent counterparts are used as visual indicators on

almost every electrical appliance. “White LED’s” are even available now to

replace Edison’s incandescent light bulb

are used in every CD player and

their less optically coherent counterparts are used as visual indicators on

almost every electrical appliance. “White LED’s” are even available now to

replace Edison’s incandescent light bulb

used for ambient lighting. Even

“Solar Cells” used to directly convert the sun’s energy to electricity are

made of diodes. In some ways, Semiconductor Diodes have filled more application

fields than any other electronic component. Perhaps that’s not bad for

something that begun from accidental contacts between rusting metal surfaces and

early broadcast “AM” radio receivers made from fine wire probes searching

for trace selenium deposits on common lumps of coal

used for ambient lighting. Even

“Solar Cells” used to directly convert the sun’s energy to electricity are

made of diodes. In some ways, Semiconductor Diodes have filled more application

fields than any other electronic component. Perhaps that’s not bad for

something that begun from accidental contacts between rusting metal surfaces and

early broadcast “AM” radio receivers made from fine wire probes searching

for trace selenium deposits on common lumps of coal

.

.

This document describes the construction

and characteristics of the following diode classes.

- Early

Semiconductor Diode (or Diode Like) Devices

-

The

“Coherer” used to receive slow speed Morse code radio messages

-

The

Copper Oxide “Battery Charger” Rectifier

-

The

Higher Voltage “Selenium” Rectifier

-

The

Small Signal Audio Diode, Also Based on Selenium

-

The

First RF Component, The Germanium Point Contact Signal Diode

- More

Recent Semiconductor Diodes

-

The

Germanium PN-Junction Diode Used For Switching

-

The

Tunnel Diode (Or Esaki Diode after its Inventor Leo Esaki)

- Modern

Semiconductor P-N and Related Junction Diodes

-

The

Silicon Diode Used For Switching

-

The

Schottky Diode Used For High Speed Rectification and Microwave Applications

-

Silicon

and Gallium Arsenide Variable Capacitance “Varactor” or “Varicap” Diodes

Used For Electronic Tuning in Filters and Oscillators

-

Silicon

Zener and Avalanche Diodes Used For Voltage Regulation and Clamping

-

Silicon

P-I-N Diodes Use For Variable Attenuation and Band Switching

-

Photo-Detector

Diodes

-

Solar

Cell Diodes

-

Light

Emitting Diodes (LED’s and also LASER Diode)

The electrical characteristics for the

following topics are also described in further detail.

- Reverse

Biased Varicap Diode C-V Characteristics

- PIN

Diode Carrier Lifetime

and its Relationship to

Intermodulation Distortion

and its Relationship to

Intermodulation Distortion

- Forward

Biased PN-Junction Diode “Charge Based” Capacitance

An appendix containing various MATHCAD

Demonstrating files is also included in this document.

The semiconductor age has revolutionised

electronics with miniaturised circuits performing convenient, advanced signal

processing functions. Semiconductor devices are used for power electronics,

audio amplification, radio frequency amplification, optical processing and

digital computations.

Prior to this we lived in a land of

wires, relays, twine and sealing wax. Even the emergence of De Forest’s vacuum

tube

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

The semiconductor promise was one of

reduced size and heat, both of which beckoned more complex signal processing

tasks to be performed. As the number of semiconductor components increased,

reliability issues became increasingly important. Anecdotal stories of house

sized computers built with vacuum tubes serviced by teams of technicians

repairing defects every few hours are easily found. The translation to

transistors, at first based on at least one occasion by the “point contact”

germanium transistor improved this situation considerably. The grand centre

stage show belongs to the invention of the integrated circuit, for which the

photographic process used for device definition and interconnection has become

tuned to a fine art. Resolutions available today parade themselves at a fraction

of the wavelength of light used for creating the lithographic screens used for

device fabrication. Complexity, Heat and Reliability issues are now replaced by

those associated with Software Reliability.

The ocean going ships of the time had

crude communication technologies, involving the use of semaphore for

transferring simple messages, or the use of loud fog-horn calls to at least

state occupancy in fog laden seas. In isolation, Nikola Tesla had been

experimenting with coils that made high voltage discharges, with a dream in mind

of sending electronic power between the continents of the world, huddled between

the blankets of transmission line effects between the planets surface and its

ionosphere. Equally remote, Marconi also played with sparks, sending them from

the ends of one wire loop into the gap of another. In some “lair of

Frankenstein” way both experiments sparked forth the birth of a new

communications industry. However, the distances electric fields could cross only

existed within the confines of a small experimenter’s room. For sea-to-land

communications, something more sensitive than the electrical breakdown of air

was needed. However, on the positive side (no pun intended), ocean going ships

with their massive diesel generators had almost unlimited power to send.

I guess some people thought about this

and reasoned that the distance of the receiving spark gap was the other part of

the problem. (Perhaps there are transactions on this subject?) How could the gap

be made smaller so that the tiny sparks could fly across and make their mark?

One idea was to fill a glass tube with

rusting iron filings. Electrodes were attached to each end, and a source of

voltage was applied through headphones. Normally the iron filings would make

poor contact, but when a RF pulse came along some of the filings would arc and

short, allowing a DC current to pass.

The

“coherer” was actually quite sensitive at detecting RF signals

but it could only do it once. Once fired, it continued to conduct,

making it a “1 bit detector”. The operator had to tap it loose

after each headphone click and it would be ready for action again.

More advanced arrangements attempted to automate this procedure,

but at least slow reception of Morse-code clicks could be

received.

|

|

Morse Code was the coherer’s domain

and it was firmly thought to be there to stay. Or so it seemed – until De

Forest’s vacuum diode came along, and the coherer’s brief life was over.

The semiconductor based rectification

properties of various metal oxides had been observed long before the invention

of the vacuum tube diode. Of these, rectifiers formed from copper disks

sandwiched between iron ones were popular. Their main application was for low

frequency AC to DC conversion, such as that required for car battery charging.

However these assemblies had a relatively low reverse breakdown voltage and

several disks were needed to rectify AC voltages even as low as 6 V AC. The

unfortunate consequence was relatively inefficient AC to DC conversion

efficiency due to the cumulative forward voltage drop of each individual

rectifying disk. In addition, the screwed down washer-by-washer construction was

not suited to automated construction, although the cost of each iron washer and

insulating disc was low.

Selenium rectifiers followed copper

oxide devices, and were best suited to lower current, high voltage rectification

such as required by valve high tension DC supplies up to 250 V DC. They were

also based on a stacked construction, but thin rectangular slabs were used

instead of washers. Some small signal “selenium diodes” were also produced,

used for audio clipping applications such as car AM radio impulse noise blanker

applications.

Selenium rectifiers survived for some

time as high voltage rectifiers in valve based AM radios for medium and short

wave broadcast radios, based on their relatively small size compared to a

dedicated rectifier tube, absence of a heated cathode and relatively low cost.

Germanium rectifiers were possible at the time, based on alloy junction

construction, but had high leakage current, especially with the temperatures

expected in a typical valve radio. The high voltages encountered were also a

major stumbling block, as the several hundreds of volts required in vacuum tube

radios was far high than the 30 V average best ratings of Germanium. Even if

these obstacles were overcome, device failure due to “thermal runaway” was

probable. Leakage current made worse by increasing temperature lead to

additional heating that further exacerbated the leakage problem. Device

destruction soon followed. Given this, even stacked series combinations of

Germanium diodes were never feasible.

Consequently, Selenium rectifiers lasted

right up to the advent of Silicon junction diodes, coinciding about the time of

the “planar” photolithographic process. These new improved Silicon devices

sprang into the spotlight immediately, armed with forward voltage drops less

than 1 Volt and reverse blocking capability exceeding 400 Volts, even to 100

Volts with minor tweaks. Overnight, once again, old technology was tossed out

from its comfortable home in favour of the new, and the selenium rectifier’s

days of notoriety were over even faster than it ousted the copper oxide

rectifier that previously overthrew the vacuum valve.

Point contact diodes can be formed by

pressure contact between a metal electrode and a semi-conductive substance. The

earliest signal detection applications might have involved “Paul Hogan” and

his captured men fingering a piece of coal at “Stalag 9” in a TV episode of

“Hogan’s Hero’s”, or so when young we might have believed. Such episodes

often portrayed a captured soldier straining to hear an allied radio broadcast

on a pair of army issue magnetic headphones, right under the nose of the

imprisoning “Colonel Clink”. A lump of coal, in this case poised against the

spring of a wire whisker, would have contained traces of selenium and containing

carbon, was adequately conductive as a substrate. Hence the first “TV Radio

Diode!” bought AM (short-wave?) messages to the troops.

Commercial production of point contact

diodes began early, fuelled by the communication needs of WW1, but also because

they were easy to manufacture, and with profit, also their low self-capacitance

made them useful for Radar detection. The standard semiconductor was Germanium.

|

|

Germanium point contact

diodes were originally housed in metal containers and used for

microwave signal detection in early radar systems

. For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder. . For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.

Diodes preceded the

invention of the transistor but became used with them as a simple

AM detector in AM Broadcast transistor radios.

|

|

Germanium point contact diodes had

reverse leakage currents in the order of 1 uA, and a forward voltage drop around

0.2 V at currents less than 1 mA. They were well suited to RF signal detection

at frequencies up to several hundred MHz even in their commercial cylindrical

glass package, due to their low self-capacitance usually less than 0.5 pF.

The PN junction was formed from

impurities in the wire contact (Tungsten, etc) combining with the Germanium

crystal. This was often assisted by “forming”, a process whereby a short

electronic pulse was passed between the electrodes. This helped to establish a

secure and stable PN region.

Note:

In this way the Germanium point contact diode does not resemble a “Schottky”

diode, which is based on a direct metal to semiconductor junction. Although a

Germanium point contact diode may use a metal contact, this contact is used to

form a P-N junction immediately under its tip, and the metal wire contact then

becomes a simple connecting electrode.

The semiconductor age has revolutionised

electronics with miniaturised circuits performing convenient, advanced signal

processing functions. Semiconductor devices are used for power electronics,

audio amplification, radio frequency amplification, optical processing and

digital computations.

Prior to this we lived in a land of

wires, relays, twine and sealing wax. Even the emergence of De Forest’s vacuum

tube

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

The semiconductor promise was one of

reduced size and heat, both of which beckoned more complex signal processing

tasks to be performed. As the number of semiconductor components increased,

reliability issues became increasingly important. Anecdotal stories of house

sized computers built with vacuum tubes serviced by teams of technicians

repairing defects every few hours are easily found. The translation to

transistors, at first based on at least one occasion by the “point contact”

germanium transistor improved this situation considerably. The grand centre

stage show belongs to the invention of the integrated circuit, for which the

photographic process used for device definition and interconnection has become

tuned to a fine art. Resolutions available today parade themselves at a fraction

of the wavelength of light used for creating the lithographic screens used for

device fabrication. Complexity, Heat and Reliability issues are now replaced by

those associated with Software Reliability.

The ocean going ships of the time had

crude communication technologies, involving the use of semaphore for

transferring simple messages, or the use of loud fog-horn calls to at least

state occupancy in fog laden seas. In isolation, Nikola Tesla had been

experimenting with coils that made high voltage discharges, with a dream in mind

of sending electronic power between the continents of the world, huddled between

the blankets of transmission line effects between the planets surface and its

ionosphere. Equally remote, Marconi also played with sparks, sending them from

the ends of one wire loop into the gap of another. In some “lair of

Frankenstein” way both experiments sparked forth the birth of a new

communications industry. However, the distances electric fields could cross only

existed within the confines of a small experimenter’s room. For sea-to-land

communications, something more sensitive than the electrical breakdown of air

was needed. However, on the positive side (no pun intended), ocean going ships

with their massive diesel generators had almost unlimited power to send.

I guess some people thought about this

and reasoned that the distance of the receiving spark gap was the other part of

the problem. (Perhaps there are transactions on this subject?) How could the gap

be made smaller so that the tiny sparks could fly across and make their mark?

One idea was to fill a glass tube with

rusting iron filings. Electrodes were attached to each end, and a source of

voltage was applied through headphones. Normally the iron filings would make

poor contact, but when a RF pulse came along some of the filings would arc and

short, allowing a DC current to pass.

The

“coherer” was actually quite sensitive at detecting RF signals

but it could only do it once. Once fired, it continued to conduct,

making it a “1 bit detector”. The operator had to tap it loose

after each headphone click and it would be ready for action again.

More advanced arrangements attempted to automate this procedure,

but at least slow reception of Morse-code clicks could be

received.

|

|

Morse Code was the coherer’s domain

and it was firmly thought to be there to stay. Or so it seemed – until De

Forest’s vacuum diode came along, and the coherer’s brief life was over.

The semiconductor based rectification

properties of various metal oxides had been observed long before the invention

of the vacuum tube diode. Of these, rectifiers formed from copper disks

sandwiched between iron ones were popular. Their main application was for low

frequency AC to DC conversion, such as that required for car battery charging.

However these assemblies had a relatively low reverse breakdown voltage and

several disks were needed to rectify AC voltages even as low as 6 V AC. The

unfortunate consequence was relatively inefficient AC to DC conversion

efficiency due to the cumulative forward voltage drop of each individual

rectifying disk. In addition, the screwed down washer-by-washer construction was

not suited to automated construction, although the cost of each iron washer and

insulating disc was low.

Selenium rectifiers followed copper

oxide devices, and were best suited to lower current, high voltage rectification

such as required by valve high tension DC supplies up to 250 V DC. They were

also based on a stacked construction, but thin rectangular slabs were used

instead of washers. Some small signal “selenium diodes” were also produced,

used for audio clipping applications such as car AM radio impulse noise blanker

applications.

Selenium rectifiers survived for some

time as high voltage rectifiers in valve based AM radios for medium and short

wave broadcast radios, based on their relatively small size compared to a

dedicated rectifier tube, absence of a heated cathode and relatively low cost.

Germanium rectifiers were possible at the time, based on alloy junction

construction, but had high leakage current, especially with the temperatures

expected in a typical valve radio. The high voltages encountered were also a

major stumbling block, as the several hundreds of volts required in vacuum tube

radios was far high than the 30 V average best ratings of Germanium. Even if

these obstacles were overcome, device failure due to “thermal runaway” was

probable. Leakage current made worse by increasing temperature lead to

additional heating that further exacerbated the leakage problem. Device

destruction soon followed. Given this, even stacked series combinations of

Germanium diodes were never feasible.

Consequently, Selenium rectifiers lasted

right up to the advent of Silicon junction diodes, coinciding about the time of

the “planar” photolithographic process. These new improved Silicon devices

sprang into the spotlight immediately, armed with forward voltage drops less

than 1 Volt and reverse blocking capability exceeding 400 Volts, even to 100

Volts with minor tweaks. Overnight, once again, old technology was tossed out

from its comfortable home in favour of the new, and the selenium rectifier’s

days of notoriety were over even faster than it ousted the copper oxide

rectifier that previously overthrew the vacuum valve.

Point contact diodes can be formed by

pressure contact between a metal electrode and a semi-conductive substance. The

earliest signal detection applications might have involved “Paul Hogan” and

his captured men fingering a piece of coal at “Stalag 9” in a TV episode of

“Hogan’s Hero’s”, or so when young we might have believed. Such episodes

often portrayed a captured soldier straining to hear an allied radio broadcast

on a pair of army issue magnetic headphones, right under the nose of the

imprisoning “Colonel Clink”. A lump of coal, in this case poised against the

spring of a wire whisker, would have contained traces of selenium and containing

carbon, was adequately conductive as a substrate. Hence the first “TV Radio

Diode!” bought AM (short-wave?) messages to the troops.

Commercial production of point contact

diodes began early, fuelled by the communication needs of WW1, but also because

they were easy to manufacture, and with profit, also their low self-capacitance

made them useful for Radar detection. The standard semiconductor was Germanium.

|

|

Germanium point contact

diodes were originally housed in metal containers and used for

microwave signal detection in early radar systems

. For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder. . For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.

Diodes preceded the

invention of the transistor but became used with them as a simple

AM detector in AM Broadcast transistor radios.

|

|

Germanium point contact diodes had

reverse leakage currents in the order of 1 uA, and a forward voltage drop around

0.2 V at currents less than 1 mA. They were well suited to RF signal detection

at frequencies up to several hundred MHz even in their commercial cylindrical

glass package, due to their low self-capacitance usually less than 0.5 pF.

The PN junction was formed from

impurities in the wire contact (Tungsten, etc) combining with the Germanium

crystal. This was often assisted by “forming”, a process whereby a short

electronic pulse was passed between the electrodes. This helped to establish a

secure and stable PN region.

Note:

In this way the Germanium point contact diode does not resemble a “Schottky”

diode, which is based on a direct metal to semiconductor junction. Although a

Germanium point contact diode may use a metal contact, this contact is used to

form a P-N junction immediately under its tip, and the metal wire contact then

becomes a simple connecting electrode.

Although the Germanium point contact

diode enjoyed great success as a small signal detection diode, it had a

relatively high series resistance that limited its ability to handle currents

beyond a few milli-amperes or to act as logic elements in semiconductor based

computers. The small area of contact was responsible. In addition, its

electrical characteristics were unpredictable, partly due to the mechanical

nature of its formulation, the imprecise nature of “forming” and also the

uncontrolled impurities that could be expected from one Germanium crystal to the

next.

The Germanium junction diode was born

from advances in the science of growing large, chemically pure crystals.

Further, the concept of “doping” a given crystal with impurities that could

result in an excess of electrons (Arsenic doping produces N - Type material) or

an excess of holes (Boron doping produces P- Type material) was in hand during

the second-world war. Chemical vapour deposition could then be used to create an

accurate PN junction on a single Germanium wafer, which could then be bonded to

or pressed against suitable wire electrodes.

|

|

Germanium junction diodes

intended for small signal switching applications were usually

based on the “point contact” construction using a small glass

envelope. However, these diodes had a doped + Type region which

the “whisker” contact made electrical connection with. These

diodes were often doped using Gold, resulting in lower series

resistance than would otherwise occur.

|

|

Germanium semiconductor junction diodes

reigned up to the 1970’s, used mainly in discrete semiconductor based computer

mainframe equipment. They formed simple AND gates and OR gate logic elements

that required a low forward voltage drop, fast switching and acceptably low

leakage. Once again, however, the tides were turning on yet another established

technology in favour of a newer breed. Silicon had long been envied for its high

temperature resilience, up to a predicted maximum of 200 C, compared to

Germanium that failed miserably at 90 C. Although plentiful (as Silicon-Oxide or

sand), purity was a serious barrier to Silicon’s commercial use. Small

molecular imperfections could render an otherwise viable PN-Diode structure

useless, resulting in unattractively low yields.

The Silicon Junction diode was placed

“centre stage” as soon as this crystal purity barrier was broken. These

diodes soon adopted the “planar” photographically processed substrate

method, and were initially housed in the same glass envelop as their Germanium

cousins. They offered a low cost, ultra low reverse leakage diode with excellent

RF and switching characteristics. They even replaced the familiar Germanium

point contact diode in AM radio detector circuits, especially when these also

switched to silicon planar transistors instead of slower, low gain and

temperature intolerant Germanium devices.

Today’s Silicon junction diodes are

constructed simply without te potentially unreliable wire contact

(“whiskerless diode”) and have changed very little from their introduction

around 1960. A planar lithographic process is used, and surface mount housing is

now standard unless high power dissipation is required.

The Silicon (Si) junction diode consists

of a N-Type substrate with a Diffused P-Type upper surface. Metal contacts are

made to each surface for electrical connection. Potential “Intrinsic”

semiconductors and their potential “Doping” elements can be seen as adjacent

columns in the following periodic table,

Truncated

Periodic Table

|

Period

|

III-A

3-A

|

IV-A

|

|

Advantages

of IVA Semiconductor

|

Use

|

|

Row

|

|

2

|

B

Boron

|

C

Carbon

|

N

Nitrogen

|

Very-High Temperature

|

Future

|

|

3

|

|

Si

Silicon

|

P

Phosphorous

|

High Temperature, Cheap

|

Common

|

|

4

|

Ga

Gallium

|

Ge

Germanium

|

As

Arsenic

|

|

Obsolete

By itself

|

|

5

|

In

Indium

|

|

Sb

Antimony

|

Sb used for infrared detect

|

TBD

|

|

6

|

Ti

Titanium

|

Pb

Lead

|

Bi

Bismuth

|

(Galena=PbS

+ cats-whisker)

|

X-Shield

|

|

Donor

|

P-Type

|

Intrinsic

Semi

|

N-Type

|

|

|

The P-N junction requires a chemical

bond to be formed, usually by heated diffusion of a donor into the intrinsic

semiconductor or semiconductor previously doped with the opposite polarity

donor. Although N-Type material has an excess of electrons, it is not

electrically charged. P-Type is also electrically neutral. The main carrier of

charge in N-Type material is the negatively charged electron, whilst the main

charge carrier in P-Type material is the positively charged “hole”,

In the absence of any applied voltage, a

“depletion” layer of hole and electron pairs form at the P-N junction, much

like opposite sides of soldiers lining up for a battle. Neither can permanently

cross the barrier height of the junction on their own, as their energy is much

less than the energy height of the P-N junction barrier. They have a finite

probability of being on the opposite side at any time, based on the mutual

attraction of opposite charges, and also the repelling force of same charge

carriers. The average separation of these charges is referred to as the

“depletion layer”, since the P-Type semiconductor is depleted of holes in

this region, and the N-Type semiconductor is depleted of electrons.

The average density of this “depletion

charge” can be shaped by the presence of an external voltage field. Imagine

that the positive terminal of a battery is connected to the P-Type Anode,

and that the negative terminal is connected to the N-Type Cathode. The

positively charged holes will be repelled by the positive charge on the Anode,

and be forced down into the depletion region. Likewise, the negatively charged

electrons will be repelled by the negative charge on the Anode and be repelled

upwards to the depletion region. Electrons and holes will “recombine” in the

depletion region, effectively passing through each other much the same way as a

drop of rain would pass through an air bubble rising from the ocean.

We will include an indicator Lamp in

series to show the effect of current flow.

Conversely, if the battery polarity is

reversed, the positive holes will be attracted to the now negatively charged

Anode and the electrons will be attracted to the positive Cathode. Unlike the

previous forward biased condition, in which the depletion layer was

squashed together, now the width of the depletion layer increases. No

recombination can occur, and therefore a complete current path is not available.

Consequently, reverse bias results in blocked current flow.

In practice, conduction is relative.

Some current will flow in the reverse direction due to the small presence of

holes in N-Type material and electrons in P-Type material. In addition, surface

mechanisms for additional leakage may exist. In general, most P-N junctions

closely follow a I-V transfer function given by,

…(1)

…(1)

Here

refers to the current flowing from

Anode to Cathode,

refers to the current flowing from

Anode to Cathode,

refers to the voltage from Anode to

Cathode.

refers to the voltage from Anode to

Cathode.

is a “saturation current”

parameter relative to the particular diode (and is temperature dependant) and k

is a constant defined as,

is a “saturation current”

parameter relative to the particular diode (and is temperature dependant) and k

is a constant defined as,

…(2)

…(2)

The constant

represents the electron charge,

represents the electron charge,

is Boltzman’s Constant and

is Boltzman’s Constant and

is an “ideality factor”

depending on the particular diode and semiconductor base.

is an “ideality factor”

depending on the particular diode and semiconductor base.

The PN-Junction diode can be used for RF

rectification up to about 100 MHz but becomes limited in its upper frequency

capability due to charge storage time. When electrons and holes “combine” in

the depletion time, it takes a finite time before they can “pass through”

and separate. This “charge storage” time causes the diode to remain

conducting for a short time even when it is reverse biased. Consequently,

rectification efficiency becomes impaired, falling to almost zero when the

charge storage time equals one half period of the RF signal frequency.

Schottky diodes are usually constructed

as from a Silicon N+ strongly doped material base with a thin N Type Silicon

Epitaxial layer on top. A non-ohmic metal contact is placed on top and this

creates a depletion zone at this junction. The difference in material “work

functions” creates a potential barrier, but in this case only majority

carriers are involved (electrons in both the N Expitaxial layer and the metal

contact). This results in an equivalent “P-N” junction but without the need

for electron-hole recombination. The previous recovery time delay is therefore

avoided, and the turn off time of a Schottky diode is limited only by its

internal capacitance and series resistance. Equivalent values of

are typical for RF Schottky diodes,

compared to

are typical for RF Schottky diodes,

compared to

for small signal junction switching

diodes like the leaded 1N4148 or its SMD BAV99 equivalent.

for small signal junction switching

diodes like the leaded 1N4148 or its SMD BAV99 equivalent.

|

|

The Schottky diode is used

as an RF Mixer and RF level detector well above 50 GHz. Different

metals define its “barrier height”, which is an indication of

the forward voltage needed to produce a defined current. Low

barrier devices draw 1 mA at ~200 mV. High barrier types might

require ~400 mV for 1 mA of current but have a higher reverse

breakdown limit, up to 70 V currently.

|

|

It is also possible to

make Schottky diodes from P-Type material. These tend to have low

reverse breakdown strength but can rectify with zero bias. They

are best suited for “square law” signal strength detectors,

which produce a voltage proportional to RF power.

|

|

PIN diodes are almost the exact opposite

of Schottky diodes in that they seek specifically to have very long charge

storage times.

The P-Intrinsic-N or PIN

diode has a layer of pure (un-doped) intrinsic Silicon sandwiched

between the familiar P and N doped areas. This middle intrinsic

layer “traps” hole and electron charges and as a result, the

PIN diode takes a relatively long time to turn off, when reverse

biased. The amount of trapped charge depends on the current and

the volume of the intrinsic layer. Typical recombination times can

be in the order of microseconds. As a result, the PIN diode makes

a poor rectifier at RF, but can be made into a switch, or a

current controlled RF resistor.

|

|

Zener diodes and Avalanche diodes have

the same basic PN junction structure but operate with completely different

physical mechanisms.

All PN diodes are photosensitive to some

extent, but different semiconductor materials can modify sensitivity and

wavelength specificity.

Electrical characteristics can often be

classified into the following convenient categories,

- Static

DC Characteristics

- Dynamic

(Incremental, Audio) Characteristics

- AC

Characteristics (RF Small Signal Behaviour)

Static

and

and

relationships are a useful “first

step” in appreciated a given device’s electrical behaviour. Simple passive

components such as resistors have a simple linear relationship between

quantities of voltage and current, but most semiconductor devices don’t.

Instead they have an added dimension of non-linear electrical behaviour.

relationships are a useful “first

step” in appreciated a given device’s electrical behaviour. Simple passive

components such as resistors have a simple linear relationship between

quantities of voltage and current, but most semiconductor devices don’t.

Instead they have an added dimension of non-linear electrical behaviour.

In many cases, these simple DC

characteristics can be considered in terms of yes/no logic. For example a

reverse biased diode can be considered to be “non conducting”, and a forward

biased diode as “conducting”. Further we can add some if’s and buts for

further clarification. For example a reverse biased diode is “non

conducting” unless its voltage breakdown limit is exceeded. Then it is

conducting again. Equally, a forward biased diode “conducts” if its forward

bias exceeds a certain threshold. An in both cases, some temperature dependency

may exist.

…(1)

…(1)

5.2.2

Advanced PN Junction Diode Thermal-Electrical Model

A more accurate theoretical expression

for the PN Junction diode’s thermal-electrical behaviour is,

…(2)

…(2)

Equation (2) provides an accurate model

for forward biased diodes.

This can be used in the forward biased

region but fails miserably in predicting reverse bias behaviour in any real PN

junction diode. For example, the term

tends to zero quite quickly as

tends to zero quite quickly as

. Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

. Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

5.2.3

Example 1N4148 PN Junction Diode Data (Fairchild Semiconductor)

Fairly common small signal Silicon

Junction diodes include the 1N914, 1N4148, BAV70 etc. These have a typical Vak{Ia}

exponential DC characteristic curve

Silicon diodes are often referred to as

having a “turn on voltage” of about 0.7 V, but this “threshold” is

largely an illusion.

is relative to the current at which this

“turn on” knee is defined as can be seen in the following graph.

This MATHCAD demonstration uses the

following equations and constants,

The first graph displays the diode

current I in a log scale, and no evidence of a “turn on voltage knee” is

visible. However, the use of a linear scale in the second graph gives the

appearance of a clearly defined turn on region at about 0.7 Volts. Is this a

real characteristic or an illusion based on the choice of scale? Interestingly,

if we rewrite equation (1) as

…(2)

…(2)

This form “suggests” the existence

of a “turn on voltage”

but the value is slightly higher

than the value that might be interpreted from the preceding MATHCAD graph.

Although the form of equation (2) could be used, it is less compact than

equation (1) in that an additional coefficient

but the value is slightly higher

than the value that might be interpreted from the preceding MATHCAD graph.

Although the form of equation (2) could be used, it is less compact than

equation (1) in that an additional coefficient

is introduced without any

corresponding new information or detail.

is introduced without any

corresponding new information or detail.

Sometimes it is convenient to separate

the diode DC equation into simper regions and make some reasonable

approximations, as previously. A

typical diode has

at room temperature. Also, the exponential is usually very large or very small

compared to 1 for most bias voltages. If we consider three regions for Forward

Bias, Zero Bias and Reverse Bias defined as,

at room temperature. Also, the exponential is usually very large or very small

compared to 1 for most bias voltages. If we consider three regions for Forward

Bias, Zero Bias and Reverse Bias defined as,

…(3)

…(3)

This three-region split is sufficiently

accurate for most purposes and is much easier to remember.

Real diodes have additional DC

imperfections that modify their electrical behaviour. Although the voltage

directly across the junction can be expected to comply accurately with equation

(1), some additional voltage drop will occur between the junction and the diode

lead due to the finite series resistance of the semiconductor material. This

voltage loss will equal

where

where

represents the total series

resistance. In addition, surface imperfections may cause additional leakage

currents to flow, which will be especially apparent in the reverse biased

condition. For example, an insulation resistance as high as 1,000 Meg-Ohms at

–10 V reverse bias will create a leakage current of 10 nA, i.e. much greater

than the expected diode saturation current of 10-15 Amps (0.001 pA!).

Equation (2) could therefore be re-expressed as,

represents the total series

resistance. In addition, surface imperfections may cause additional leakage

currents to flow, which will be especially apparent in the reverse biased

condition. For example, an insulation resistance as high as 1,000 Meg-Ohms at

–10 V reverse bias will create a leakage current of 10 nA, i.e. much greater

than the expected diode saturation current of 10-15 Amps (0.001 pA!).

Equation (2) could therefore be re-expressed as,

…(3)

…(3)

The expression for Anode current

based on applied forward bias has

no closed form solution, and will require numerical methods to find an accurate

solution especially if the voltage drop caused by series resistance

based on applied forward bias has

no closed form solution, and will require numerical methods to find an accurate

solution especially if the voltage drop caused by series resistance

is large.

is large.

The solution for device voltage

based on forward current

based on forward current

is straightforward in comparison,

is straightforward in comparison,

…(4)

…(4)

Semiconductors can withstand an

electrical field up to a point where electrons or holes are ripped from their

outer orbits. When this occurs, the freed charges allow conduction and large

currents could flow. If the current is limited, this “breakdown” mode could

be used to advantage as a way of providing voltage regulation. Diodes used for

voltage regulation are called “Zener diodes”, but most are actually

“Avalanche diodes”. This breakdown mechanism occurs at a clearly defined

threshold, but is slightly temperature dependent. The construction is similar to

a standard PN junction diode, except that doping arrangements are chosen that

define a required breakdown limit.

Avalanche behaviour usually dominates

for reverse voltages greater than 5 Volts. Junction diodes can easily achieve

breakdown voltages up to 1000 Volts and higher (1N4007 1 Amp 100 V rectifier as

an example). Diodes designed for voltage regulation are typically available in

steps from a few volts up to 50 Volts or more. An interesting phenomena

regarding noise generation also occurs in this region. Several mV of wide band

noise may be observed after avalanche behaviour occurs. In some cases, this may

be useful as a source of broad-band noise, or in other cases it may be an

unwelcome nuisance.

True Zener diode behaviour is based on

quantum mechanical effects, which become effective at lower breakdown voltages

in highly doped diodes. A comparison of typical V-I curves shows a clear

difference between the two modes of voltage regulation,

|

|

Zener

diodes usually have breakdown ratings below 5.6 Volts, whilst

Avalanche diodes typically exists with breakdown voltages above

5.6 Volts. The Zener behavior shows a rounded “knee” and

therefore provides relatively poor voltage regulation unless the

supplied diode reverse current is kept constant. The Avalanche

region in contrast is very sharp, and shows a slope that depends

mainly on the diodes’s series resistance

.

.

|

|

In most applications, IC based voltage

references are the preferred option for accurate voltage regulation and have

excellent temperature and stability. “Zener” diodes are still useful as a

low cost method for clamping unwanted signal voltage “spikes”. They are also

used as simple voltage references in less critical applications.

A

series resistor is used to limit current to an appropriate value,

but this current must be greater than any additional current

required from its regulated output. This “parallel” regulation

mode is not as energy efficient as other methods, and as such is

only used in low current situations involving several milli-amps.

|

|

5.4.1

More General Diode Equation For Thermal Prediction

A more accurate theoretical expression

for the PN Junction diode’s thermal-electrical behaviour is,

…(5)

…(5)

This can be used in the forward biased

region but fails miserably in predicting reverse bias behaviour in any real PN

junction diode. For example, the term

tends to zero quite quickly as

tends to zero quite quickly as

. Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

. Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

…(6)

…(6)

Let use define a reference room

temperature of

and a resulting reverse anode

current

and a resulting reverse anode

current

measured under this temperature

condition. The ratio of reverse current

measured under this temperature

condition. The ratio of reverse current

at temperature

at temperature

to this reference reverse current

to this reference reverse current

at temperature

at temperature

would then be,

would then be,

…(7) Note – a very poor estimator of reverse diode current!

…(7) Note – a very poor estimator of reverse diode current!

The reverse leakage current for a PN

Junction diode typically doubles for every 8-degree rise in temperature.

Equation (7) clearly does not display this relationship, and in fact suggests a decrease

in current for rising temperature. A more practical equation for reverse bias

leakage current is,

…(8)

…(8)

In addition, real PN junction diodes

display an increase in reverse leakage current with increasing reverse bias that

appears close to a straight line fit when the current is plotted on a

Logarithmic axis.

…(8)

…(8)

Note: The negative

sign is included on the exponential exponent as

for reverse biased operation.

for reverse biased operation.

It would seem that a dual variable

equation could be formed from the product of equation (7) and (8), i.e.

…(9)

…(9)

This new expression appears to have no

dependency on reverse bias voltage, which we know from measurement to be untrue.

Equation (6) will however demonstrate a general temperature dependency and will

therefore be pursued.

5.4.2

The Effect Of Temperature On The PN-Junction Diode’s Forward Voltage

The PN Junction diode has an explicit

temperature dependant term

in its exponential V-I equation.

The effect of this would be to cause the current to change over temperature when

Vak is held constant, or for Vak to change when Ia

is held constant. However it is not the only temperature dependant term

in its exponential V-I equation.

The effect of this would be to cause the current to change over temperature when

Vak is held constant, or for Vak to change when Ia

is held constant. However it is not the only temperature dependant term

We will first re-write equation (1) so

that the diode forward bias voltage Vak is the subject

…(5)

…(5)

Let us now differentiate equation (5)

where the temperature T is treated as the main variable,

…(6)

…(6)

Consequently, we find that

…(7)

…(7)

Equation (7) shows us that the

percentage change in absolute temperature equals the percentage change the

diode’s forward voltage drop, for a given fixed anode current.

At room temperature, T = 273K + 25C =

298K. A 1 degree change in temperature will therefore cause in a voltage change

of 2.35 mV for a diode biased with a current corresponding to an initial forward

voltage of 0.7 Volts.

Differentiating with respect to

temperature

Making Vak the subject

In many cases it is useful to know the

incremental current and or voltage behaviour of a given component so that its

small signal, low frequency characteristics can be ascertained. This analysis is

usually provided for the forward bias case.

…(4) (for the purpose of this

analysis the relationship will be defined)

…(4) (for the purpose of this

analysis the relationship will be defined)

Differentiating with respect to voltage

we find,

…(5)

…(5)

The “dynamic conductance”

is directly proportional to the

junction diode’s forward bias current

is directly proportional to the

junction diode’s forward bias current

and since resistance is defined as

the reciprocal of conductance we can also state,

and since resistance is defined as

the reciprocal of conductance we can also state,

…(6)

…(6)

where

. The junction diode can now be seen to provide a current dependent conductance

or resistance to small signal perturbations compared to its forward bias current

. The junction diode can now be seen to provide a current dependent conductance

or resistance to small signal perturbations compared to its forward bias current

. We can also gain some insight into its non- linear properties in the forward

bias region by expanding equation (4) as a Taylor series,

. We can also gain some insight into its non- linear properties in the forward

bias region by expanding equation (4) as a Taylor series,

…(7)

…(7)

In this case

represents a small perturbation in

voltage around a given forward bias voltage

represents a small perturbation in

voltage around a given forward bias voltage

. Also note the n=1 tern corresponds to the previous expression for the dynamic

conductance

. Also note the n=1 tern corresponds to the previous expression for the dynamic

conductance

. The n=2 term is also of interest for small signal detection and frequency

mixing. In this case

. The n=2 term is also of interest for small signal detection and frequency

mixing. In this case

…(8)

…(8)

From equation (8)

where

where

, therefore,

, therefore,

…(9)

…(9)

The average current can be found by

integrating equation (9)

ignoring the cosine term and subtracting

the forward bias current,

·

Ignore

Junction Capacitance

·

Ignore

Stored Charge

·

Ignore

Lead Inductance

·

Forward

Biased Junction Diodes Exhibit Current Dependent Capacitance

·

This is

Due To Charge Stored in The Junction

…(6)

…(6)

Consider

the hypothetical Junction Diode

V ~ 0.7 V, I = 10 mA -> 0 mA, Time

to remove this charge and turn off,

to remove this charge and turn off,

ó

C{ 10 mA } = 57 pF !!

(Note that the reverse capacitance

for such a diode might only be < 2 pF!! )

(Note Also – This Capacitance

Will Be In Parallel With Rd = 2.5 Ohms)

·

Can Be

Found From V{I} Curve Fit

·

Usually

~ 5 Ohms or so for 1N4148 etc

·

Requires

High Reverse Voltage To Remove Charge Due To Rs

·

Diode Has Current Dependent

Dynamic Resistance Rd.

·

Diode Has Voltage and Current

Dependent Parallel Capacitance C

·

Diode Construction Also Has

Series Ohmic Resistance Rs

·

Package Has Lead Inductance Ls

|

|

Composite Junction

Diode Model

A reversed biased junction (and

Schottky) diode will exhibit classical “soft” varicap behaviour given by,

…(5)

…(5)

The coefficients can be determined by DC

curve fit approaches and an accurate match is usually obtained.

Note: Some Hyper Abrupt varicap diodes

may exhibit a negative Cp !!!

Semiconductors

had shown non linear properties such as rectification up to this point in time,

but the domain of signal amplification belonged to the vacuum tube triode,

tetrode and later the pentode. The vacuum devices had evolved significantly with

time, and became small enough to operate as hearing aid amplifiers and operate

from voltages as low as 9 Volts. They still required a heated (red) hot cathode

filament, which only served to

waste energy and shorten battery life.

The

idea of a “solid state” amplifying device remained elusive until Schottky

and his team at Bell labs finally resolved previous failed attempts at

semiconductor based amplification. The structure they invented was based on a

single Germanium crystal mounted on a metal electrode with two closely spaced

gold metal strips pressed on to its surface. These formed the “Emitter” and

“Collector” terminals, and the metal mounting plate formed the “Base”.

This

early experimental transistor had a common base current gain of about 2, and

although this was a very low value of amplification even by the standards of the

time, in was nonetheless evidence of amplification potential. Commercial

interest in manufacturable devices followed immediately, and many experimental

“point contact” germanium devices were produced. These used a similar

construction to their point contact diode predecessors, but were difficult to

manufacture as the two wire “whiskers” had to be placed within less than

th of a millimetre of each other for transistor action to occur.

th of a millimetre of each other for transistor action to occur.

Point

contact transistors were unusual in so far as they exhibited a common base

current gain greater than one, but could still be used in common emitter

configurations with appropriate bias. They had a Noise Figure in excess of 30

dB, which by today’s standards is abysmal, but could operate up to several MHz

due to the low self-capacitance of their contact leads. Although demonstrated in

a working computer application, they did not find their way into commercial

radio applications, and lasted only a few years before ousted by the Germanium

Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT).

The Germanium Point

Contact Transistor could achieve a common base current gain

between 2~3 times, a voltage gain up to 500 times, and a power

gain in the order of 1000 times (30 dB), given ideal conditions.

However they were mechanically and thermally fragile, required

critical bias control and could only handle a few mA of current at

several volts. Their physics of controlling surface current flow,

it is said, remains unsolved to this day.

|

|

![]() ...............................................

4

...............................................

4

![]() and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications............................................................................................................................................

8

and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications............................................................................................................................................

8

![]() 9

9

![]()

![]() , dual polarity transient energy suppression

, dual polarity transient energy suppression

![]() and electronically tuned filters

and electronically tuned filters

![]() found in AM and FM car radios and

TV sets. They are used in microwave applications that require electronic control

of signal amplitude and also provide protection against high amplitude signal

microwave signal pulses. Photo detection diodes

found in AM and FM car radios and

TV sets. They are used in microwave applications that require electronic control

of signal amplitude and also provide protection against high amplitude signal

microwave signal pulses. Photo detection diodes

![]() are available for infrared energy

and light, and can even be used for optical wavelength conversion when combined

with a Laser Local Oscillator source. Optically “pure” Laser Light Emitting

Diodes (LED’s)

are available for infrared energy

and light, and can even be used for optical wavelength conversion when combined

with a Laser Local Oscillator source. Optically “pure” Laser Light Emitting

Diodes (LED’s)

![]() are used in every CD player and

their less optically coherent counterparts are used as visual indicators on

almost every electrical appliance. “White LED’s” are even available now to

replace Edison’s incandescent light bulb

are used in every CD player and

their less optically coherent counterparts are used as visual indicators on

almost every electrical appliance. “White LED’s” are even available now to

replace Edison’s incandescent light bulb

used for ambient lighting. Even

“Solar Cells” used to directly convert the sun’s energy to electricity are

made of diodes. In some ways, Semiconductor Diodes have filled more application

fields than any other electronic component. Perhaps that’s not bad for

something that begun from accidental contacts between rusting metal surfaces and

early broadcast “AM” radio receivers made from fine wire probes searching

for trace selenium deposits on common lumps of coal

used for ambient lighting. Even

“Solar Cells” used to directly convert the sun’s energy to electricity are

made of diodes. In some ways, Semiconductor Diodes have filled more application

fields than any other electronic component. Perhaps that’s not bad for

something that begun from accidental contacts between rusting metal surfaces and

early broadcast “AM” radio receivers made from fine wire probes searching

for trace selenium deposits on common lumps of coal

![]()

![]() .

. and its Relationship to

Intermodulation Distortion

and its Relationship to

Intermodulation Distortion belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

![]() and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications

and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications

![]()

![]() . For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.

. For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

belonged to an era of hand-connected components mounted on bent, drilled and

machined metal chassis bolted into equally hand crafted wooded cabinets.

Although nostalgic to some, individual production of such expensive items was

never an ambition of the industrial revolution. Mass production, based on

repetitive tasks, each being a sub component of the whole, was the enviable

position to be attained. Towards this end we saw the use of PCB substrates

supporting leaded components and socket held valves, each searing their

surroundings with heat for the purpose of relatively simple signal processing.

![]() and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications

and

Small Signal Audio Limiter Applications

![]()

![]() . For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.

. For commercial

applications the sturdy metal housing was replaced with a lower

cost drawn glass cylinder.![]()

![]() …(1)

…(1)![]() refers to the current flowing from

Anode to Cathode,

refers to the current flowing from

Anode to Cathode,

![]() refers to the voltage from Anode to

Cathode.

refers to the voltage from Anode to

Cathode.

![]() is a “saturation current”

parameter relative to the particular diode (and is temperature dependant) and k

is a constant defined as,

is a “saturation current”

parameter relative to the particular diode (and is temperature dependant) and k

is a constant defined as,![]() …(2)

…(2)![]() represents the electron charge,

represents the electron charge,

![]() is Boltzman’s Constant and

is Boltzman’s Constant and

![]() is an “ideality factor”

depending on the particular diode and semiconductor base.

is an “ideality factor”

depending on the particular diode and semiconductor base.![]() are typical for RF Schottky diodes,

compared to

are typical for RF Schottky diodes,

compared to

![]() for small signal junction switching

diodes like the leaded 1N4148 or its SMD BAV99 equivalent.

for small signal junction switching

diodes like the leaded 1N4148 or its SMD BAV99 equivalent.

![]() and

and

![]() relationships are a useful “first

step” in appreciated a given device’s electrical behaviour. Simple passive

components such as resistors have a simple linear relationship between

quantities of voltage and current, but most semiconductor devices don’t.

Instead they have an added dimension of non-linear electrical behaviour.

relationships are a useful “first

step” in appreciated a given device’s electrical behaviour. Simple passive

components such as resistors have a simple linear relationship between

quantities of voltage and current, but most semiconductor devices don’t.

Instead they have an added dimension of non-linear electrical behaviour.![]() that is typically described by the

following exponential current versus voltage transfer equation,

that is typically described by the

following exponential current versus voltage transfer equation,![]() appears to be a

constant, it is actually strongly temperature dependent.

appears to be a

constant, it is actually strongly temperature dependent. …(1)

…(1) …(2)

…(2)![]() tends to zero quite quickly as

tends to zero quite quickly as

![]() . Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

. Equation (5) could therefore be simplified,

…(2)

…(2)![]() but the value is slightly higher

than the value that might be interpreted from the preceding MATHCAD graph.