HISTORIES=PLATEAUS by Carlos A. Romay Vergara

2/5. CONNEXIONS AND LINKS IN TIME.

| Initial | Chapter 0 | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 |

| Main Page | Instructions | Concepts | Connexions | Questionings | Structures | Differences |

Summary:

1. The Theatre of Quotidian Life.

2. Loos: Limits and Irruption.

3. The Destruction of the Relationship Between Interior

and Exterior in Loos’s Oeuvre.

4. Activity. The Portrait in Movement.

5. How Difference evolves.

6. Bibliography.

Two lines of History may be linked though separated by time and space. As a matter of fact, this connexion may be established between different spatial and temporal historic lines that have similarities or that influence one on the other. Hence, what is the link between a house by Adolf Loos in 1928’s Vienna and, through a leap in time and space, a house by Japanese-Scottish office Ushida Findlay built in Tokyo, 1993? If there is such a relationship, what is its consequence for Architecture?

Firstly, it must be highlighted that Adolf Loos’s (1870-1933) career is ampler than his celebrated article ‘Ornament and Crime’. Loos was an architect that argued for a separation between the proposition of space and the respect for tradition. He did not want to define ‘inhabiting’ through given architectural definitions that he considered stylistic and determinist (especially those of the Viennese Sezession Group). To Loos, lifestyles, habits and furniture were not properties and objects modifiable according to styles, but important part of the existence of the people. Nevertheless, Loos introduced determinism as part of his ambiguous discourse on mobility. He proposed the movement and control through the Raumplan spatial configuration and, on the other hand, he precluded the introduction of the notion of movement into the building. Furthermore, his discourse established differences with that of the first dogmatic and formal Modernists.

In Hilde Heynen’s book ‘Architecture and Modernity’, Loos’s architecture “…did not immediately win him the same recognition as his writings. This was largely because it was fundamentally at variance with the ideals of the modern movement and was therefore incompatible with the historiography of Gideon and Pevsner. The attitude adopted toward him was often ambivalent. He was respected and celebrated as a pioneer of ‘modern architecture’ with repeated reference to ‘Ornament und Verbrechen’-the only article he wrote that became really famous. His other articles and the buildings that he actually built remained largely unnoticed and undiscussed for a long time. In particular, his invention of the Raumplan, the three dimensional design, met with little response from his contemporaries”. (Heynen, p.75)

The topic of the relationship between interior and exterior is fundamental in Loos’s oeuvre. Loos’s vision on modernity was influenced by its positive and negative qualities, thus influencing his work. In this point, we may ask some questions in order to relate Loos’s work with that of Ushida Findlay: How was the evolution of the relationship between interior and exterior since the Viennese bourgeoisie days of the 1920’s to the time of consumerism of modern Japan? How has the notion of Modernity changed more than seventy years between one building and the other?

1. The Theatre of Quotidian Life.

The first information in order to establish a relationship between Loos and Ushida Findlay is that in the year of 1974 Eisaku Ushida presented a thesis on a house that Loos planned for actress, singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Ushida proposed a methodology derived from the Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard for the study of the mentioned house. In this thesis Ushida surely assimilated concepts and ideas that were important for the development of Loos’s oeuvre (in this case the notion of Raumplan).

The Raumplan (German word where Raum=space) designates a spatial configuration where the multi-level plan consists of a strongly oriented unique space in which points of observation and control are established. It is characterized by the tri-dimensional orientation of the spatial layout and by the incorporation of syntactical elements such as stairs, half levels, voids, fills and in general, by the proposition of a flexible and multi-purpose space. It is neither a functionalist nor structuralist space, even more, it constitutes a diagram.

| A) |

B)  |

C)  |

D)  |

A) Adolf Loos, Moller House, Axonometry of Interior. (Heynen, p.83); B) A.Loos, Moller House; Vienna, 1928, front façade (Heynen, p. 81). C) A. Loos; Moller House, The ladies' Lounge (http://www.geocities.com/ darq_estudio/lecorbu/lo02.jpg); D) A. Loos, interior of Moller House, (Häuser 6/94; Hamburgo; pg. 10).

In Loos’s oeuvre, and especially in the Moller House, the architect attributes different areas to the control of different members of the family. Hilde Heynen defines and comments over the Raumplan’s characteristics in the work of Loos: “His houses get their very specific character due to the alternation of different atmospheres and to the contrast between light and dark, high and low, small and large, intimate and formal. And yet this plurality of spatial experiences is unified in a certain sense, since the experiences are brought together by the Raumplan, a technique of designing in three dimensions that Loos regarded as his most important contribution to architecture. Designing for Loos involves a complex three dimensional activity: it is like a jigsaw puzzle with spatial units of different heights that have to be defined first and fitted into a single volume afterward”. (Heynen, p.80)

Furthermore, the word ‘complex’ designates the interplay of two apparently opposed notions that in the case of the Moller House are control and liberty. Control exists because Loos locates certain points that dominate the observation of the course of the guests along the house, especially in the stairs and levels connected visually in the lounge areas. Liberty exists since the Raumplan is not a functionalist space that forces directionality; on the other hand it enhances constant exploration and unexpected journeys. In Loos’s Moller House this traced itineraries are multiple and ever-changing, labyrinthine.

In the aforementioned house (Vienna, 1928) the sequence of living areas is built around a central hall. Once entering the small entrance, the visitor must turn left and mount a flight of six steps to the cloakroom. After the somewhat suffocating feeling of the entrance, this feels like a first breathing space. The route continues: once again the visitor climbs a flight of stairs-this time with a bend in it; only then one arrive in the huge hall that comprises the heart of the house. The rooms with a specific function are grouped around the periphery of the high-ceilinged salon which is a ‘ladies’ lounge’ (Damenzimmer) abutting on the front façade and built a few steps higher than the level of the hall. The music room is in the same level as the hall and abuts on the rear façade. Immediately adjoining it and four steps higher we find the dining room, which also abuts on the rear façade. (Heynen, p. 83-84). Hence, the trajectory is a theatre of flows where one is always observed by those who know the strategic points. The notion of theatricality, typical of Loos’s houses and of the Raumplan, is depicted by Beatriz Colomina in Heynen’s book: “The house is the stage for the theater of the family, a place where people are born and live and die.”(Heynen, p. 80, quoting Beatriz Colomina’s essay “The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism” in Colomina’s book “Sexuality and Space”).

Heynen extends on the notion of theatricality in the Moller House by Loos: “This theatricality may be seen in the way Loos creates a choreography of arrivals and departures: through the frequent shifts in direction that oblige one to pause for a moment, and through the transition between the dark entrance and the light living area, one gets a sense of deliberately entering a stage set-the stage of everyday life”.(Heynen, p. 82-83).

On the other hand, in the Chiaroscuro House in Tokyo, the Ushida Findlay team proposes the Raumplan in the house project of an artist who wanted to live with his family in a ‘bright and colorful’ house. That is the rationale of the exploration of the chiaroscuro, the technique of the emphatic treatment of light and shadows in painting. The house evolves through different heights and through intermediate levels and points of observation of space that facilitate the comprehension of the whole, as in the Moller House by Loos.

Apparently in the Chiaroscuro House, the architects succeeded in obtaining a more quotidian and open space than in the Moller House by Loos, nevertheless, this affirmation is relative since the notion of the ‘quotidian’ may have changed since the 1930’s. Chiaroscuro House’s atmosphere is more illuminated and relaxed than the Moller House, and the materials and colors help attaining this sensation. The penetration of light is outstanding and inviting. The materials chosen by Ushida Findlay establish a sharp contrast with the sobriety of Loos’s Moller House. Nevertheless, the theatricality has not been postponed. The high space of the Raumplan in Chiaroscuro is a scenario for various imaginary journeys in a theatrical play, proposed for the repetition of quotidian acts not deprived of expectation as space has been designed for observation.

Paul Carter writes in his essay ‘Introduction to Ushida Findlay Works’ (in architectural magazine 2G #6), that this theatricality refers to the play of drama that characterizes the Japanese-Scottish office: “It is this subconscious architecture of transitory noises, ephemeral faces and out-of-focus shadows which supplies the mise-en-scène of a dire emotional renegotiation, one that admits back in the madness, and renders the meander, sometimes the headlong flight, essential furniture of the soul’s future living place”. (2G Ushida Findlay #6, p. 9)

Both houses, Moller and Chiaroscuro, exploit the dynamic movement that constitutes the ‘Idea of a Scenario’ for life and for quotidian emotions. In both houses, theatricality as action and the image proposed as photography, root them deeply with art, with moving scenes whose ground is architecture and the space formed by intentionally redundant elements (the stairs) which incite continuous movement. Theatre (movement) and painting (architecture as backdrop), are related through the construction of a scenario where in effect there are stage boxes for the contemplation of the repetition of the quotidian and every day’s activity: In the Moller house the stage box is the “ladies’ lounge’ and in the Chiaroscuro House, two rooms that dominate the space of double height located at each side of the final fly of stairs. Moreover, in the Moller House by Loos, the similarity of the flight of stairs with a painting is interesting. Like in a Modern play, we find flights of stairs with different directions that overlay like the scenery of a play in which the movement of characters expressed the rupture with the modern that Loos worried greatly.

Deleuze wrote in ‘Le Pli’ (pg. 51) that Loos follows baroque architecture, in the sense of the tacit division between interior and exterior, as the diagram of the baroque of a house of two stages where the base is the body and the first floor is the mind. Both floors are not connected directly, and such is the caesura of the relationship between exterior and interior: “Such is the baroque feature: an exterior always in the exterior, an interior always in the interior. An infinite ‘receptivity’, an infinite ‘spontaneity’: the external façade for the reception and the internal chambers for the action. Until now, Baroque architecture will not cease facing two principles, one of sustentation and the other as principle of coating (sometimes Gropius and others Loos)”. (Deleuze quotes Bernard Cache’s book L'Ameublement du Territoire).

2. Loos: Limits and Irruption.

In general terms, the exclusion of exteriority in the Moller House is performed by the reinforcement of limits. Walls take charge of delimitation, working as impermeable, solid, impenetrable elements, capable of defending the family’s precious intimacy in the midst of an ever changing and unpredictable situation: “This duality of inside and outside is achieved by providing a good design for the boundary-that is, for the walls. It is here, according to Loos, in the distinction between outside and outside, that architecture comes to its own…In Loos’s view, the important thing was to draw clear distinctions between different areas in the house, and to set up definite boundaries between them. The architectural quality of a building lay in the way that this interplay of demarcation and transitions was handled, in the structuring of the different areas, and in defining their relationship.” (Heynen, p. 76)

Loos reinforced the differences of the hard limit of exterior-interior through the opening of gaps in strategic positions for the interior. The openings are never in random position; furthermore, the house, as a heavy box of filtration of light and the exterior absorbs only what is useful in order to reinforce the internal control system of the spaces in the Raumplan. Internal organization does not appear to the exterior (neither will it in Ushida Findlay’s house except for the large windows of the street façade).

Beatriz Colomina refers to the particularity of the exclusion of the exterior in Loos’s house in these terms: “…with Loos, windows are not normally designed to be looked out of. They function in the first instance as a source of light; what is more, they are often opaque or are situated above eye level…All this means that the interior is experienced as a secluded and intimate area. Nowhere does the space outside penetrate the house. While partition walls are often absent in the interior, replaced by large openings between two spaces, every transition to the outside is very clearly defined as a door and not as an opening in the wall. The transition between inside and outside is often modified by a flight of steps, a terrace, a verandah”. (Heynen, p. 88).

Loos proposed the Raumplan in order to perform a synthesis of different types of space, but in certain places in the Moller house he reversed the effect dissolving the walls with reflecting surfaces or mirrors, which he used as elements which interrupted the fixed hard limits. In this way, he amplified even more the interiority, since walls reflect the own interior of the house, which turns even more self-referential: Spaces within other spaces, not as in the case of paintings, which transport to other landscapes and situations, but as a circularly-defined space, always referred to itself. Interiority was exacerbated.

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

A) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, view of street façade. (2G #6; p.42). B) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, view of the space of the Raumplan (2G #6; p. 48). C) Adolf Loos, Moller House, view of the ladies' lounge (Heynen; p. 46). D) Adolf Loos, Moller House; View of the stairs. (http://www.via-arquitectura.net/13/13-024.htm)

D)  |

E)  |

F)  |

E) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, view of the rooms that comprise the Raumplan. F) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, view of the system of stairs. (2G # 6; p. 47-49)

Hilde Heynen refers to the strong notion of limits and the topic of materials on the oeuvre of Loos: “The most striking thing in Loos’s houses is the unique way that the experience of domesticity and bourgeois comfort is combined with disruptive effects. The different rooms that contrast so sharply with each other are linked together and kept in balance by the sheer force of the Raumplan; one does, however, constantly encounter influences that make for disunity…Sometimes mirrors or reflecting surfaces are combined with windows, serving to undermine the role of the walls, because their unambiguous function as partitions between indoors and outdoors is threatened. There is a distinct interplay between the openness of the Raumplan that coordinates all the rooms and the completely individual spatial definition that distinguishes each room separately, due to the materials used and details such as ceiling surrounds, floor patterns, and wall coverings…This, too, makes for an ambiguous experience of space; on the one hand one feels these are well-defined spaces, with clear protective boundaries, but on the other hand one is aware it is quite possible that one is under the gaze of an unseen person elsewhere in the house. The sense of comfort is not unqualified, but is upset at regular intervals by disruptive effects.”(Heynen, p. 89)

For Loos, the richness of the play of domestic powers (spaces for the observation and control) cannot be neither penetrated nor questioned by occasional pedestrians that walk in front of the house, who are not able to imagine what the closed volumes of the Moller House hide. This type of organization of space is indeed representative of the negative relationship that Loos thought existed between interior (domesticity) and exterior (irruption).

Consequently, is the Raumplan a diagram of Power? In this sense, philosopher Gilles Deleuze wrote that it is possible to speak of a diagram of power that extends itself though qualified knowledge, furthermore mentioning Foucault when he wrote that “ensuring one self’s direction, exercising the direction of his own house and participating in the city government are three practices of the same type”. (Foucault, p. 131). Hence, in itself the Raumplan is a diagram of power, since it has been designed for the observation and control on others. The possibility of exercising the power is, in this case, optional but always present.

3. The Destruction of the Relationship Between Interior and Exterior in Loos's Oeuvre.

The Raumplan in the Moller House allows the attainment of the critical void for a rich articulation of the space to the interior. Moreover, the Raumplan’s void was, especially for Loos, the void of traditional life allocating its memories and precluding them from external references. The privilege of the interior over the exterior was an unquestionable concept for Loos: In the Moller House, there was a rupture between interior and exterior that the house signified. In Loos’s own words, the preeminence of interior over exterior must be represented: “The house should be discrete in the outside; its entire richness should be disclosed in the inside”. (Heynen, p. 76). The Moller House is neither transparent nor proclaims an extreme originality in the exterior, thus isolating itself to the interior. The characteristic that puts accent on the external mass of the house of clad masonry are small openings in the simple volume. According to the same historic period, the house established a contrast with other houses where interiority was revealed by means of exposed glass and structure, as in the pieces of work of pioneers of modern architecture like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius.

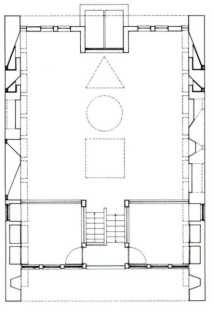

|

Adolf Loos, Moller House, Plans and Section. (Heynen, p. 82).

Why did Loos forbid the relationship with exteriority over the influence of modernity? For Loos, in words of Hilde Heynen, “…dwelling may only happen if it is insulated from the metropolis, not in relation to it. Anonimity and concealment are essential conditions if dwelling is to survive within the modern world-this is the implication of an analysis of Loos’s houses….Dwelling has to be entrusted to the interior: only there do the conditions exist for an unquestioning garnering of memories; only there may one’s personal history take on form. Only through this retreating movement may dwelling realize itself and achieve authenticity. (Heynen, p. 94)

Loos established a reticence in his connection with the exterior. Carlos Muñoz Gutierrez, professor of Philosophy in the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, in his essay entitled “Wittgenstein Architect: The Thought as a Building”, establishes a link between Loos and the thought of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, friend Loos’s benefactor. Muñoz refers especially to the influence of constructive experience on Wittgenstein’s philosophy. In English2 magazine Astrágalo, Muñoz Gutierrez compared Loos’s rupture with the exterior with the experience of building the Kundmanngasse, a house that Wittgenstein planned and built between 1926 and 1928 in Vienna. Through his constructive experience, Wittgenstein realized the linguistic translation of the project from the concept to the building was impossible, although he recognized this impossibility simultaneously through his philosophy and through constructive process.

It is important to trace the influences over Loos in order to determine the trajectory of his thought and interests on his oeuvre. The thesis I propose is that Loos reduced the inherent potential of the Moller House trying to translate his negative thought on Modernity, betraying the relationship with the exterior. I propose that the analogy of thought and concretion led Loos to isolate the building (the Moller House) from its environment, thus precluding its external possibilities. This relationship was finally accomplished by Ushida Findlay (through the Raumplan) almost seventy years later in another part of the globe.

Carlos Muñoz Gutierrez synthesizes the aversion that Loos felt to modern interference in his architecture, establishing a difference with Wittgenstein’s oeuvre: “Effectively, we see the difference between Loos, the architect, and Wittgenstein, the philosopher. Loos (or Architecture in general) insisted in constructing buildings that constituted fortresses that prevented us from its perils. But Wittgenstein necessarily had to confront the perils of the world, hitting again and again against the walls that he eagerly wanted to trespass. Wittgenstein knew another solution to the unstoppable chain of exact representations that the building of thought is: to come out to the exterior, not to build oneself but to dilute in the whole, to fuse in the mesh and to contemplate the world as a whole, ‘sub specie aeterni’. This is the mystic, perhaps the program of his austere and minimalist life, that in the end he did not succeed to achieve or, if he did, it could not be expressed with language as he knew.” (Astrágalo, p. 126-127)

As a matter of fact, Wittgenstein’s thought initially resembled that of Loos’s. Muñoz Gutierrez explains that “programmatic and stylistic coincidences between Loos and Wittgenstein, in a first glance, should assure an evident communion. Nevertheless, there is a dire difference that will appear as the paths of architect and philosopher profile neatly”. (Astrágalo, p. 121). The wealthy bourgeois origin of Wittgenstein was initially in contradiction with the deep social and organizational changes that Modernism brought. Muñoz Gutierrez writes that “…for Wittgenstein…ethic and aesthetic hold a special equivalence-and they should maintain this equivalence; Wittgenstein’s functional style (maybe minimal) should alleviate him from the evil, the excess, the fright that produced on him quotidian life. Against the Loosian device, ‘Das Praktische ist Schön’ (functional is beautiful), Wittgenstein could have produced ‘Nothing that distracts me, nothing that take me away from what is important’. (Astrágalo, p. 121). Wittgenstein’s translation of his thought (ethic) into aesthetic determined his inclination to intervening in architecture, as a means of constructing the building of his thought.

(In this point I differ from Muñoz Gutierrez, who translates the German word Praktische as functional; probably the translation may be reduced to ‘practical’ (Collins German Dictionary, Grijalbo, 1997; Mexico; pg. 138), so that Loos’s relationship with functionalism is less evident. We may change the notion of ‘practical’ to ‘the pragmatic’, which assumes another sense, the sense of the immediate, of non-speculative. But again Loos falls in the dogma of denying the sense of pragmatism in order to prevail his aversion to exterior. Exterior could have assumed the role of the pragmatic, in this case. Ushida Findlay proposes a less discursive relationship for the understanding of the environment in their Chiaroscuro House.

Wittgenstein’s Kundmangasse House and Loos’s Moller House belong to the same year (1928) in their concretion, but they produce as a result two totally different visions from the building of the concepts. This fact produced tensions and resentment between Loos and Wittgenstein, especially because the first thought that the intervention of a philosopher into architecture was an intermission. Muñoz Gutierrez tells the differences in an misfortunate encounter between both architect and philosopher nine years prior to the building of the mentioned houses. In a letter that Wittgenstein wrote to P. Engelmann, Loos’s pupil before the war of 1919, Wittgenstein described the encounter he had with the architect: “Days before I met Loos…¡He has been infected with the most pretended virulent intellectualism¡ He gave me a pamphlet over a proposed ‘Office for the Beaux Arts’, in which he writes of a sin against the Holy Spirit. ¡This is enough¡ I was a little depressed when I met Loos, but this was too much for me.” (Astrágalo, p. 122).

Muñoz Gutierrez adds that in 1921, Loos dedicated Wittgenstein his article ‘Written in the Void’ that he wrote for the Neue Freie Presse paper, in which he warmly thanked his inspiration, hoping that Wittgenstein devoted the same feeling. (Astrágalo, p. 122). This demonstrates that friendship and intellectual interchange between Loos and Wittgenstein existed and that the last thought that Loos had at least deceived their intellectual relationship in order to enclose in a different proposal.

In his aforementioned essay Muñoz Gutierrez proposes that Wittgenstein undertakes the search for a theory of knowledge based on representation, but that in the end he realizes that the path is wrong: “Thinking produces a scaled construction of the building of the world but the tragedy lies here: when we start to build our thought with the bricks that only provides us, we are doing it from the inside, so that in the end, the building shows us what we enclosed in its interior cannot contemplate. The shape of the building would be an exact rejoinder of the world, but from inside we may just follow our existence as we did before building it…This is probably the most inadmissible consequence that Wittgenstein struggled against eagerly, although it is true that the solution is conditioned to a reconsideration of the language that stops being the vehicle of thought and representation…In that sense he believed to have found a mediating element that might have been the link. Then he elaborated his theory of knowledge thinking that an exact representation of the world might contain the adequate model of our wishes, but certainly, at the end, he understood that this was a misconception.”(Astrágalo, p. 124-125, p. 134).

M.M. Rosental and P.F. Ludin wrote that ‘logical atomism’ is a conception formulated among others by Wittgenstein in his Logical-Philosophical treatise: ‘According to logic atomism, the whole World forms a whole of non-related atomic facts…Philosophy of logic atomism…asserts the existence of a multiplicity of singular things and deny that such things form a unity, a totality…All knowledge is interpreted as a whole of “atomic” propositions related through logic operations. The structure of the world is inferred, analogically, through the logic structure of knowledge’.(Rosental and Ludin, pg. 28-29). Wittgenstein as well as Loos proposed a building that was the image of the world according to their own vision. From the Kundmangasse, Wittgenstein extrapolated the conclusions that took him to think that there is no coherent totality but a whole of structured facts in different systems among which there is no relationship.

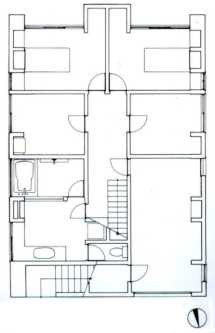

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Kundmangasse House; A) Plan; B) Façades; C) Volume. (Astragalo, p. 116).

On the other hand and architecturally, the conclusion of an analysis of both Moller and Kundmangasse houses by Loos and Wittgenstein respectively reveals that the last is less original, especially because of the traditional spatial layout and organization of the rooms, possibly attributable to Wittgenstein’s social experience. In that sense, he did not propose a radical rupture with the traditional Viennese bourgeoisie house. He devoted more to exhaustive constructive details because of his formation as mechanic engineer.

Wittgenstein’s purpose was obtaining a correct analogy between construction and philosophy, a purpose that he finally did not attain concluding his building. As a whole, the building is still very unitary to be translated into independent and non related-among-them parts. This could have implied a re-elaboration of the house social relationships that Wittgenstein did not accomplish. The ground floor reveals an undifferentiated vast free space. Wittgenstein rejects hierarchies and in place he proposed an ample, fluid space without territories. Externally the atomization cannot be inferred as well. Hence, I conclude that Wittgenstein did not accomplish the house as image of his thought. Finally he could not change his image of what social relationships were. (Please refer to the essay ‘Questionings to Repetition’ and Descartes’s reticence to change his philosophical project to alter domesticity).

On the other hand, Loos’s realization constituted a truly social negative critique to discursive Modernism and proportioned a contribution to new spatial configurations. For Loos, the Raumplan constituted a paradigm of configuration that he initiated in a commercial house for the Goldman and Salatsch tailors in the Michaelerplatz in Vienna (1909-1911). (Heynen, p. 89-91). His design also produced the rupture between exterior and interior. The difference between Loos and Wittgenstein is that, at the end of the constructive process, both extracted differently two conclusions. For Wittgenstein, the translation of ethics to philosophy was impossible, meanwhile for Loos there was no conflict between ethic and aesthetic: furthermore, architecture was a vehicle of the expression of thought. On the other hand, Loos’s Raumplan is not only a spatial rupture but alters human and social relationship within the building. Loos proposed what Wittgenstein did not: social alterity and its analogy with thought are given through the proposing of new spatial configurations.

Although arguable, Loos’s aversion to change and to the intrusion of the exterior over interior is what characterized his oeuvre and what he expressed firmly and with optimism, since from the first to the second Raumplan there is a difference of seventeen years, time in which Loos matured his conception that places the inhabitant as observer of his own dwelling’s interior, thus legalizing observation and control. (Loos is pessimistic over the exterior but optimistic over the interior). On the other hand, for Wittgenstein, the analog observation from the inside fails and hence it is not licit. Wittgenstein concluded that the only possibility was observing the building (of philosophy) from the outside, since from the inside it might not be understood properly.

The great difference between Loos’s and Wittgenstein’s

buildings is given through the explanation of centripetal and centrifugal forces

that act over the interior. Centripetal observation, in Loos’s case, did

not escape the strong magnetism of interior life. Furthermore, Loos rejected

the magnetism of exteriority in not pretending to attract anything from the

outside. On the other hand, in Wittgenstein’s house, the tension is centrifugal

since the interior the concept outside, at the risk of not understanding the

truly nature of the house for the involvement in the building’s interior.

Proposing Loos’s same centripetal strategy, the Chiaroscuro house by Ushida

Findlay exercises magnetism that powers the house’s interior: the interior

is strong enough to concentrate the interest of quotidian life. Consequently,

the exterior has been attenuated in order to avoid resting importance to the

centripetal way in which the house works.

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

D)  |

A) Adolf Loos, Moller House, music room seen from the dining room. (Heynen, p. 85). B) Adolf Loos; House in the Michaelerplatz; Vienna; http://www.bluffton.edu/~sullivanm/loos/ mainview.jpg). C) A. Loos, House in the Michaelerplatz, view of the building together with the neighboring Herberstein Palace (Heynen, p. 92). D) A. Loos, house in the Michaelerplatz, axonometric view of the Raumplan interior of the taylor shop.( Heynen, p. 91).

After Wittgenstein’s attempts of representation, and at the end of the state of confusion in which he fell since his construction of philosophical and architectural reality led him to a circular metaphorical process (where all elements refer to themselves), finally he adumbrated the possibility of activity being a way out of the representational dilemma: “Wittgenstein astoundingly seemed to discover that the idea of representation, in which he based his attempts of answering the problems that philosophy and life propose, is unfound, since it seems that human knowledge, which the concept of simulation resumes, may only be established on the own stable ground that it constructs. If required, grammar has the concept of simulation, capable of questioning every other, but it also constitutes a condition for possibility of conceptualizing and of representing…Wittgenstein distrusted and felt insecure of the possibilities of the concept. He felt the necessity of limiting these possibilities…Effectively, the concept lies on a type of history, on an intention…Forsaken the idea of an ideal privileged, private or at least unique language and forsaken the idea that we access to the world through the language it represents, we enter a moment of indetermination. Language multiplies itself; there is no more a unique language that we understand…Then, we have to resort to something external…but this last resource leads us to the exigency of interpretation…(which is) an endless metaphorical process…This is the interest in finding…the thought…,to use it in life, to convert it into activity.” (Astrágalo, p. 138-139, p. 141).

The concept of simulation is what Wittgenstein assimilates as the failure of representation. Isn’t simulation a metaphor, the a-critical mimesis that Enric Miralles rejected as a valid method for design? The critical mimesis of activity and the work of the concept is what Wittgenstein finally accepted as a way out of the labyrinth of representation.

4. Activity: The Portrait in Movement.

Ushida Findlay’s oeuvre rises as an interesting opposition to the forced interiority of Loos’s oeuvre. As Ushida Findlay write: “We are in dire need of a means of creating residential space based on the relationships between the body/perception and space that transcend cultural difference…rather than reinforce the shells that protect us, we must think of ourselves as open systems, taking in information from the outside while venturing outside ourselves-always in the interest of self-reform”. (Ushida Findlay, in Paul Carter’s essay ‘Translating. Towards a Sub-Conscious Architecture’; 2G #6, p. 5).

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

A) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, view of the dining room located South with views of the garden.(2G #6; Ushida Findlay; p. 45). B) Adolf Loos, Moller House, garden facade.( Heynen, p. 88). C) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, main volume in model. (2G#6; Ushida Findlay, P. 43).

In Leo van Schaik’s essay ‘Introduction to Ushida

Findlay Works’, Ushida Findlay’s oeuvre is defined as dynamic and

sensorial: “The evolving diagram of their development reveals again and

again the reflective coil of an enveloping spiral of space that enfolds the

inhabitant in reverie, while the raw in the materiality throws the imagination

back to the tactility of our sense awarenesses. (2G #6, p. 15). In Ushida Findlay’s

own words, this determination remises to three basic aspects that characterize

their projects. On the one hand, metaphors and representations are omitted,

and on the other hand, action (activity), the ephemeral and the self-referential

(references in the site) are enhanced: “We summarize the three threads

of this genealogy of spatial exploration like this:

-Spatial topology emerging from the morphology of action,

-Constructed ephemerality creating the perspective experience.

-Geometry distilled from natural structures.

In our work, each of these three preoccupations operates independently or becomes

synthesized into a hybrid form, capable of receiving a further array of constructional

and material characteristics, as we work towards the embodiment of a full architectural

existence for each project”. (Ushida Findlay, p. 131-133).

In Paul Carter’s essay ‘Translating. Towards a Sub-Conscious Architecture’, the author extends on the important issue of the ephemerality, as a new demanding requirement of modernity that Ushida Findlay have elected to face: “In what they describe as the third strand of the genealogy of their buildings Ushida Findlay talk of framing the ephemeral-in effect using detail to notate the subconscious, fluctuating environment of the chiaroscuro-.But chiaroscuro is also the real of the photograph when the overlooked details it faithfully records, that polyphony of incidentals, is allowed back in”. (2G #6, p. 10). In this sense, Chiaroscuro is a diagrammatical and open construction that reveals but not isolates, even though its appearance reminds somehow of the relatively hermetical volume of Loos’s Moller House.

The shape of Chiaroscuro is that of a cubic volume with a slightly curved metal roof. The sensation it inspires is that of a massive thick-walled body, even though the sensation of heaviness is minor than in the Moller House because of the wide transparent windows. Ushida Findlay remit to the exterior, inter-acting with the ephemeral and the ever-changing as with the Raumplan as an open diagram.

For Ushida Findlay, the Raumplan in the Chiaroscuro House allows the creation of a vast space rich in spatial articulations, in trajectories and in spontaneous fluxes. (Deleuze wrote in ‘Le Pli’ that the actualization is always different, as we never perceive ‘…the same green, the same degree of twilight’). (Deleuze, Le Pli, pg. 117). It is a building that finds antecedents in the Moller House and that at the same time it constitutes a point of departure for other projects. It accomplishes the evolution from Loos’s piece of work in order to re-interpret the relation and inter-dependence with exteriority. It is as if Chiaroscuro did not want to loose notion of the reality that surrounds it and of what it may see, feel and perceive (the lights, the movements of the trees’ leaves in front of the light filtrating walls, the heat of the sun, etc.). It is important to understand the strategy by which the ephemeral is introduced to the house (through activity, light and movement filtrated by the openings, etc.). Moreover, the notion of inter-action is key in order to understand the difference between both schemes of Raumplan.

We have to remark the self-referential properties of Ushida Findlay’s projects to understand the way in which openings and windows work in Chiaroscuro. The site is geometrically interpreted meanwhile projects are based in natural configurations which determine a system of references that uses data of previous states of the project by fractality, thus allowing the extension of the system to complex urban levels. As Reiser and Umemoto, Ushida Findlay propose scalar systems that work in order to consider the different project’s scales with a single conception.

In this specific case, Chiaroscuro windows introduce light in order to inform the interior over the changes in luminosity and character of the exterior, referencing the Raumplan’s spatiality. Leo Van Schaik defines in the following terms the work of the openings in the Chiaroscuro House: “…Site conditions forged their idea into a ‘camera obscura’ or ’light-intaking machine, in which changes in lighting conditions outside are magnified and dramatized on the inside... as if they had drawn the light envelopes as slimy drawings and made a box around them. (2G #6, p. 16)

Ushida Findlay proposes diverse degrees of permeability through the external skin constituted by thick walls. Glass blocks and window openings allow the exploration of different lighting modalities: lateral and filtrated through openings in the walls, direct through wide windows, and zenithal though geometric-shaped skylights. Compared to the Moller House by Loos, the issue of permeability is explored in deepness. The house of the painter in Chiaroscuro works as a sponge that absorbs external phenomena, creating a porous constructive tissue by which external views and (pure and filtrated) light penetrate into the building, creating a multiplicity of effects over the internal surfaces.

Furthermore, the structure is comprised into the built mass

of the whole, avoiding its expression in the form of relevant constructive elements.

The triangular elements that protrude from the walls contacting the leftover

ceiling are structural buttress that work as slab bearings against the walls.

The buttress’ closeness and profusion may occasionally be mistaken with

decoration, even though it is not. Ushida Findlay do not make use of decoration

in the Chiaroscuro House, even though it looks like they did. The cuts in the

stucco walls have all a non-decorative specific function, which is regulating

the pass of light and hiding the electric system that works when light diminishes.

Finally in Chiaroscuro, the issue of texture re-joins exterior with interior.

A strong spatula cladding applied against the walls unifies the whole house

and eliminates the rupture of interiority and exteriority. A continuous surface

that is typical of Ushida Findlay’s oeuvre is created. This feature has

relationship with other of their buildings that have very different morphology.

In summary, Chiaroscuro is a synthesis of reconciled elements. For Ushida Findlay,

the notion of exteriority is not to be fight against, as dangerous for the familiar

life and its memories. On the other hand, in Loos’s view, exterior and

interior were irreconcilable antithesis.

“No translation would be possible if in its ultimate essence it strove for likeliness to the original”. (Walter Benjamin, quoted by Paul Carter in ‘Translating. Towards a Sub-Conscious Architecture’; 2G #6, p.4).

Friedrich Kittler, wrote on the ambiguous character of mediation. Kittler wrote that in a discourse network, transposition takes the place of translation. This implies that every translation is to a certain degree incomplete, and that must invoke the essence of what is being translated: “Because the number of elements…and the rules of association are hardly ever identical, every transposition is to a degree arbitrary, a manipulation. It may appeal to nothing universal and must therefore leave gaps.” (Allen, p. 17).

In summary, once understood by Ushida Findlay that the issue of the representation of the concept may only derive in an impossible labor, it is comprehensible that the differences between both houses is mainly internal. Ushida Findlay accomplished a dynamic space fundamentally through the operations of change and movement. Referentiality in the case of the Moller House is always internal and based on the cohesion of unity. In the case of Chiaroscuro the references are external, even though the Raumplan joins all the organization of space. The notion of illumination and penetration of the external into the internal is fundamental in order to differentiate both schemes of Raumplan. The Moller House is notoriously centripetal since it privileges interior life and on purpose it closes to the exterior. This symbolic aspect is supported by Loos’s negative vision on Modernity, which he understands as the ‘lack of…’, so notorious of the rupture of Modernity and tradition.

Gilles Deleuze wrote a paragraph in his book ‘Difference

and Repetition’that might be applied to the labor of difference that Ushida

Findlay accomplished in Chiaroscuro: “The difference may be internal and

nevertheless non-conceptual...There are internal differences that dramatize

the Idea, before representing the object. The difference here is interior to

the Idea, even when it is exterior to the concept as representation of the object”.

(Difference and Repetition, p. 57). The concept of Raumplan is maintained in

reference to Loos’s oeuvre, nevertheless, the Idea of establishing the

building as something hermetical mutates in favor of converting it into something

porous.

Furthermore, Guattari and Deleuze wrote in ‘Rhizome’ that there

is the possibility of denying the image establishing an exterior that does not

have neither image, nor signification, nor subjectivity (Rhizome, p. 35), in

the search for different conditions from those of the ‘tree’ organization,

hierarchical in itself and always appealing to its self logic. In this sense,

the idea of closing the building in Loos’s Moller house constitutes a

hierarchical purpose: a ‘tree’ configuration, a ‘tracing’

over complexity. In the Chiaroscuro House, its configuration reminds a rhizome

for it is open, receptive and establisher of different types of connections

that the house does not forbid.

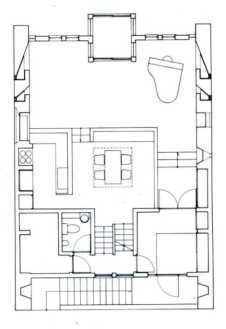

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

A) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House; Second Floor. B) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House; First Floor; C) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House; Ground Floor. (2G # 6; p. 46).

Deleuze, in ‘Difference and Repetition’ outstood the importance of movement over the copy of concept (confronting Nietzsche with Hegel in reference to theatre), arguing for a return to the movement and to the repetition with difference: “Theatre is real movement, and from all the arts that it comprises, it extracts real movement. They say: …the essence and interiority of movement, is repetition, neither opposition nor mediation. Hegel is denounced as he proposes the movement of the abstract concept instead of the movement of Physis and Psyché…He represents concepts instead of dramatic ideas: he performs a false theatre, a false drama and a false movement. It is outstanding to note how Hegel betrays and de-naturalizes what is immediate in order to found his dialectic over this incomprehension, and introduces mediation in a movement that is not more than his own thought and the generalities of this thought…The theatre of repetition opposes the theatre of representation, as movement opposes concept and the representation that relates to concept. In the theatre of repetition, what is experienced are pure forces, dynamic traces in space that act over the spirit without intermediaries and that join it directly with nature and history; a language that speaks before it say words, gestures that are elaborated before organized bodies, masks prior to bodies, ghosts and phantoms prior to the characters; all the apparatus of repetition as a ‘terrible potency’”. (Deleuze, p. 33-35).

In the previous paragraph, Deleuze established a subtle difference between the ‘abstract concept’ (that we may equalize to the ‘Idea’, as ruling concept) and the ‘concept’ properly. It is presumable that ‘the static’ (the Idea, the Abstract) is against the pragmatic, the concept, ‘the moving’. Deleuze equalized “the performing of movement” with the accomplishing of repetition with difference. Repetition is achieved in both Moller and Chiaroscuro houses twofold: Firstly, through the internal movement of the characters: The repetition of every day’s domestic life. Secondly, through the movement of the Raumplan’s closed and abstract concept to another concept which is more open and permeable. The difference lies in that a new type of movement is introduced into Ushida Findlay’s Chiaroscuro: the external movement of the surrounds, of the ever-changing that repeats every day but that is never equal. The movement of external theatre is introduced into the internal theatre in order to modify it.

In the Moller House, Loos introduced the diagram he created, i.e., the Raumplan. It is a diagram since it is a configuration of universal order –in the same way that the Le Corbusier’s Domino is a diagram of configuration and production. The Raumplan is neither a critique nor a commentary, nevertheless, Loos in the Moller house introduced the Idea as a ruling and hierarchical notion of a caesura with the exterior. Furthermore, Loos proposed a critique and a commentary in which he attenuated the abstract but pragmatic concept. Hence, Loos privileged the Idea over the Concept.

According to the Collins Dictionaries, the Idea is in Plato’s philosophy, a universal model of which all things in the same class are only imperfect imitations. The Moller House is an imperfect imitation of the Idea of caesura. On the other hand, Ushida Findlay attenuates the Idea of caesura and rather approaches the proper Concept of Raumplan, i.e., observation and control, but inclusion and movement as well as pragmatic application. What is dramatized is the Concept in the Chiaroscuro House. Furthermore, Chiaroscuro moves History and constitutes a redefinition of the Moller House, thus attaining a different and productive potential.

In order to establish a relationship between the Moller House and Chiaroscuro, Ushida Findlay neither copy nor translate Loos’s original, even more, they empower it, diffusing the Idea and assuming the Concept of the Raumplan as a porous open diagram. This is their architecture’s. virtue. Furthermore, the fulfillment of the Moller House is more abstract (by the Idea); nevertheless it is not deprived of drama.

In order to represent their oeuvre, the Ushida Findlay office proposed a diagram constituted by an irregular volume, in which Chiaroscuro has at least three important features which the diagram represents. They qualify it as a building in which a) Psycho-Geography, b) Field and c) Perception, are outstanding.

a) Psycho-Geography refers to the production of a relationship between the site and its topology. Topology, according to the Collins Dictionaries, is a branch of geometry that describes the properties of a figure that are unaffected by continuous distortion. According to the Sopena Encyclopedic Dictionary, Topology refers to the knowledge of the place. It constitutes a mnemonic method based in the association of ideas with places. Quantitative aspects are discarded in favor of Qualitative aspects. This means that for Topology, certain architectural features that are capital to the building are not directly affected by its materiality, namely, light, shadows, and movement on the exterior.

b) Field. In order to clarify the meaning of Field, Wiel

Arets’s essay “Thoughts Regarding the Condition of Fields”

will be introduced. Arets writes that we create a mental seal that changes constantly

as it is contrasted with new events through sensorial experience. Arets mentions

that it is more appropriate to relate our perception of architecture and the

strategy of design with a realm less closed that form. (Cuadernos iAZ; p. 1).This

realm is the Field. Three concepts that pertain to the ‘Field’ are

described by Arets. These concepts are common to Chiaroscuro:

1. Arets writes: “Dealing with the conditions of a Field, it is important

to establish a position by which architecture does not establishes a dialogue

with the city, but maintain with it a sufficient distance. As distance between

inhabitant and architecture exists, there is established a relationship with

the immediate”. (Cuadernos iAZ, p. 2). (This caesura of the ‘dialogue’,

reminds us of the collapse of structuralist methods in Architecture and proposes

the enhancement of the potential of phenomenology as an immediate element in

the relationship of architecture and its environment).

2. Arets writes that the Fields are loaded with information, possible scenarios,

events and forces of risk. They are always in state of transformation. In the

case of Chiaroscuro, the information is transmitted to the house’s interior

and produces a change of sceneries. (iAz; p. 2)

3. “The Fields are always in movement, in constant development, they are

never reconstructed. They are anonymous and complex”. (Cuadernos iAZ;

p.3). The movement of people in the street, the sun in the sky and the leaves

in the trees surrounding Chiaroscuro introduce the movement into the house.

The issue of the movement of the Concept against the drama of the Idea has been

mentioned before.

c) Perception. Herman Hertzberger defines it as “…the ability to extricate certain aspects from within their context so as to be able to place them in a new context”. (Hertzberger, p. 38-39). In the case of Chiaroscuro, the building works exactly as a photographic machine capable of working in changing scenarios: its physical characteristics do not depend on the context but on the work it achieves.

Stan Allen writes that diagrammatic architecture bridges the gap of associations and mediation of representation, and remarks the possibilities of local potential and immediacy that must be revealed by the project. Immediacy and diagram refer directly to Chiaroscuro: “The result is immediate, and the sense clear, a way out of the abyss of associative meaning. Further, inasmuch as these operations cannot be performed in translation, no overriding, universal sense is claimed, only the local and specific possibilities of manipulation…A diagram architecture does not justify itself on the basis of embedded content, but by its ability to multiply effects and scenarios. Diagrams function through matter/matter relationships, not matter/content relationships. They turn away from questions of meaning and interpretation, and reassert function as a legitimate problem, without the dogmas of Functionalism. The shift from translation to transposition does not so much function to shut down meaning as to collapse the process of interpretation. Meaning is located in the surface of things and in the materiality of discourse”. (Allen; ANY #23; P.17-18).

A)  |

B)  |

C)  |

D)  |

E)  |

A) and B) Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, structural elements and sources of light. (2G #6, p. 46-47); C), D) and E); Ushida Findlay, Chiaroscuro House, the infiltration of light is fined by vertical and horizontal sources. (2G#6, p. 44-49).

Moreover, the issue of transposition is important in order to understand the evolution of the Raumplan from Loos work to that of Ushida Findlay. Hence, Allen appeals to Friedrich Kittler’s definition in order to define transposition: “Whereas translation excludes all particulars in favor of a general equivalent, the transposition of media is accomplished serially, at discrete points”. (Allen, quoting Kittler in ANY 23; p. 17). The transposition from Loos’s Moller House to Ushida Findlay’s Chiaroscuro is attained via the movement, even though in this case it must be admitted that only a term of the equation may move: the one that is developed later in time. It is not a two-way transposition, from Moller House to Chiaroscuro House and vice versa: only from Moller House to Chiaroscuro. The original, the Moller House, might move or ascribe to the Concept, but the house would be destroyed in its rich contradiction). Allen extends that what is lost in the deepness of representation and the superficiality of significance is gained in immediacy (of the ephemeral, of the ever changing, of movement, of the geometry of the site, etc). A good example of what Allen describes is Ushida Findlay’s Chiaroscuro House.

In summary, both Loos and Ushida Findlay proposed the Raumplan as a diagram, as an open, flexible, modifiable, expansible configuration that may change according to vectors such as those of economy (usage, necessities, organization, fluxes, etc.), in the same way that the configuration of the Le Corbusier’s Maison Domino is a diagram. Nevertheless, the diagram of the Raumplan was used in both cases with different purposes: In Loos’s case, in order to prevent; in Ushida Findlay’s, to reveal.

(For R. E Somol, in ‘The Diagrams of Matter’, in ANY #23, p. 23, a list of diagrams of the XXth century includes the “nine square and the panopticon, the domino and the skyscraper, the face/ vase and duck/shed, the paranoid-critical diagrams and the fold, dance notation and cinematic storyboards, maternal bodies and bachelor machines”. Possibly the Raumplan may be added to the list).

|

The diagram is neither critical nor political, but on the other hand, architecture is. There is a social compromise in Architecture. The notion of development and evolution of Modernity through time evidence its change; it has introduced into our lives, not in the sense that Loos or Wittgenstein feared. Modernity must be accepted, even if we do not want. Resistance is futile. It is indeed: the second Modernity is an important moment in time for its radical social and political changes that Architecture cannot ignore. Moreover, Herman Hertzberger argues to stay attentive to social changes around design: “As an architect you must be attuned to what goes on around you; open yourself to the shifts of attention in thinking that bring certain values into view and exclude others. The extent to which you allow yourself to be influenced by these shifts is a question of vitality…Capitalize…shifts in society and in the thinking of society, and the new concepts that are discovered as a result. Architects must react to the world, not to each other.” (Hertzberger, p. 53) The information of the ephemeral and of the site is an option in order to preclude the misunderstandings of representation. The influence of immediacy is material and organizational. As Christine Buci-Glucksmann points, “that is why the ephemeral is not a passive acceptance of the present, but rather a way of capturing the modulations of beings and things, their unity and their differences”. |

Ushida Findlay, diagram of oeuvre with Chiaroscuro high lightened. (2G #6, p. 134).

6. Bibliography (Notes make reference to the following texts):

1. Heynen,

Hilde; Architecture and Modernity. A Critique; Massachusetts Institute of

Technology; 1999; 3rd Printing; 2001

2. Deleuze, Gilles; Diferencia y Repetición; Amorrortu Editores; 1st Ed.; Buenos

Aires; 2002.

3. 2G # 6: Ushida

Findlay; Editorial Gustavo Gili; Barcelona 1998/II.

4. Muñoz Gutiérrez, Carlos; “Wittgenstein Arquitecto. El pensamiento como Edificio”

en Astrágalo # 18; September 2001, Espacios, Migraciones, Alteridades; Celeste

Ediciones S.A. Instituto Español de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Alcalá;

Alcalá de Henares; Madrid.

5. van Berkel, Ben; Bos Caroline; in

Diagrams-Interactive Instruments en Operation; in ANY # 23; Cynthia Davidson

Ed.; Anyone Corp.; New York; 1998.

6. Hertberger,

Herman; Space and the Architect; 010 Publishers, Amsterdam, 2001.

7. Deleuze, Gilles; Foucault; Paidos Iberica; Barcelona; 1987.

8. Cuadernos iAZ: Pensamientos,

Wiel Arets; http://www.iaz.com/cuadernos/4bis/10.html (Cuaderno 4, 1997)

9. Somol,

R. E.; in The Diagrams of Matter; in ANY # 23; Cynthia Davidson Ed.; Anyone

Corp.; New York; 1998.

10. Buci-Glucksmann,

Christine; From the cartographical View to the Virtual; http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/no-stop-city/

11. Boesiger, Willy; Le Corbusier; Estudio Paperback; Ed. Gustavo Gili; Barcelona;

1980.

12. Collins Dictionaries; Intense Educational Ltd. (UK); 2003.

13. Enciclopedia Universal Sopena; Ed. Sopena; Barcelona; 1971.

14. Harvey, David; Urbanismo y Desigualdad Social, Siglo XXI

de España Editores; 3ra Ed, Madrid, 1985. (Social Justice and the City,

Edward Arnold Publishers, London, 1973).

15. M.M. Rosental y P.F. Ludin, Diccionario de Filosofía; AKAL Editor,

Madrid, 1975.

16. Deleuze, Gilles; El Pliegue; Paidós Básica; Barcelona 1989

| Initial | Chapter 0 | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 |

| Main Page | Instructions | Concepts | Connexions | Questionings | Structures | Differences |