|

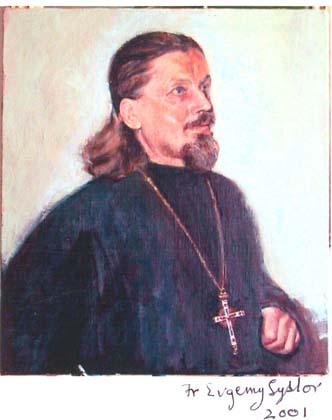

Mitred Archpriest Eugene Lyzlov

1901-1982

Founder of the Russian Orthodox Church of Our Lady,

Joy of All Who Sorrow, Philadelphia

Bludgeoned by terror,

by sorrow exhausted,

in the land of the free

we seek peace in our hearts.

Joy of All Who Sorrow!

Most holy Mother,

we believe in Thy powerful sheltering hand. |

The founder of our parish, Father Eugene Lyzlov, was born January 14, 1901 into a priestly family in the village of Kozulino near Smolensk. His father, Father Photios, was a descendant of a long line of priests that started in the times of Ivan the Terrible. Fr. Eugene’s mother, Anastasia (maiden name Kasatkin), was a niece of the equal to the apostles St. Nicholas, the first Orthodox archbishop of Japan (feast day 3/16 February).

All together, there were 12 children in the family, five of whom died in infancy. As their granddaughter Z.I. Peters tells it, Fr. Photios and Matushka Anastasia were true unmercenaries and as such earned the love of the peasants.

These deeply religious and people-loving parents by their own example demonstrated to their son the grace-filled characteristics of the soul: humility, unacquisitiveness, hard work and respect for people regardless of their ethnicity or social position. The future pastor had learned from childhood the meaning of true active love. The family kept personal belongings of the highly revered St. Nicholas, archbishop of Japan. The great-uncle’s example inspired Eugene to overcome life’s pains and sorrows. Since 1917 this was to be Soviet life, which brought so much sorrow to his priestly life.

In the fateful year of 1917, Eugene graduated from Gymnasium (high school) in the town of Beliy. In the fall of 1918 he was conscripted into the Red Army, but thanks to his beautiful handwriting spent the Civil War as a clerk in Smolensk.

After the war, Eugene successfully completed Smolensk Seminary. On January 27, 1923, he married Natalia Smirnova, a deeply religious daughter of a peasant, Mikhey Vladimirovich Smirnov. Thereafter, Eugene was ordained a deacon in Smolensk and then in 1925, on the day of St. Alexis the Man of God, he was ordained a priest.

The ordination of the 24-year-old Fr. Eugene took place at a most inauspicious time for a priest. Only a few days afterwards, Patriarch St. Tikhon died. The everyday life of Russian priests was unbearable. The “machine” of militant atheism rolled through the country, suppressing any and all expressions of faith. Priests and deacons were arrested, shipped to camps, executed, beaten, evicted from their homes and separated from their families. Parishioners were persecuted for participation in church life. A godless lifestyle was being established in the country. The Russian Church itself was experiencing the most difficult unrest, splits and the Living Church movement of renovationism backed by the Soviets.

The tribulations of those times did not pass by Fr. Eugene, for he survived assassination attempts, arrests and the seemingly unavoidable threat of execution. Yet in those harsh years he restored churches, enlarged his parishes and fearlessly confronted the authorities. Perhaps it was the prayers of his family, including the intercession of his great-uncle St. Nicholas, or that of St. Alexis the Man of God. Perhaps it was the unceasing prayers of all the poor whom Father, himself poor, loved to help. Perhaps it was all of the above, but miraculously he was always saved.

In 1937 Fr. Eugene received a new ID card. Thanks to a clerical error, it said he was a “civil servant,” not a “cult servant,” which meant he could find a layman’s job, which he did. To be more precise, he found several: teaching math, chemistry and music, and working with deaf and mute children. He did not serve as a priest at this point but remained a priest. Of course, he was a deeply religious person. As for us, we believe the Lord preserved him for a new mission — to serve those thirsting after Christ’s truth in new conditions. Those conditions were of the horrible unheard-of war of 1941-45, “the Great Patriotic War” as it is called in Russia.

“Mercilessness from the arrogant invader [the Germans], who saw the Soviet person as merely a two-legged animal. An animal which was hunted, starving and dying, and used to the limit. He then was exterminated as no longer needed.

“Mercilessness from the Soviet power, and its faithful servants, who saw the luckless, tormented Soviet middle class as a disdained mass. A mass which was obligated to obey and to work to their death for the glory of Communism.” (From “The Traitor” by Vladimir Gerlakh).

It was probably in 1942 that Fr. Eugene began to serve again as a priest, and to work very actively on behalf of the Soviet POWs and civilians. When necessary, he fearlessly confronted the German authorities. Fr. Eugene himself collected clothes and shoes for our soldiers and then pulled the sledge full of goods to the POW camp. He heard Confessions and gave Communion in the camp and in the jail. He performed baptisms, sometimes up to a hundred per day. The hungry life and constant danger became for the Orthodox an unceasing preparation for Confession and Communion of the Holy Gifts. Each day could become the day of a personal Golgotha. For this patience, the hearts of the humble and the prayerful were generously graced by the presence of the Holy Spirit. Twice at the point of a gun, it was this grace alone that Fr. Eugene from German execution.

In 1944, the Lyzlov family was shipped to Germany as Ost-arbeiteren — Eastern workers. They lived through never-ending air raids and shellings, slave labor and, finally, American occupation. Like many others, the Lyzlovs were sent to a “displaced persons” (DP) camp at Kempten in western Germany. There they were to endure another horrific ordeal — forced, so-called “repatriation” to the Soviet Union. Unwilling, anti-Communist people were forced into the Communists’ grasp, with the help of the U.S. and British armies!

Z.I. Peters describes it thus:

“... there came a detachment of American military police. They were all chewing gum... We heard an order: ‘Come out voluntarily, whoever is a Soviet citizen.’ We all locked our arms. Fr. Eugene was standing with the Cross in the middle of the row. The Americans started beating and shoving us. Fr. Eugene lost all his teeth; the Cross was bent. My sister Irene was beaten to a pulp. I myself still bear a scar from the impact of the gun. I remember Zarevsky. The father was lowering his child from the window and a soldier of the MP shot him in the back. Six people threw themselves from the fifth-floor windows. People slashed their wrists, hanged themselves. They threw us in the trucks as if we were firewood. After a short ride we were forced into cattle cars...”

Only a miracle and the UN’s intercession delivered the Lyzlovs and a few other families from this fate. The Lord saved Fr. Eugene from jail and execution, preparing him for the next phase of his difficult pastoral life — serving Russian emigrants first in Germany and then in the U.S.

From Kempten, like many others the Lyzlovs were transferred to a DP camp in Fussen and then in Schleisheim. It was a very special place: here lived three metropolitans, two archbishops, 22 priests, dozens of professors, engineers, teachers, doctors, artists, actors and many others. Notwithstanding the general poverty and uncertainty, the religious, cultural and educational life literally flourished. And of course Fr. Eugene took an active part in it. Having endured the horrors of war, hardened and frightened, the Russian people built walls around themselves. But even so, they flocked around Bat’ushka and found comfort in him.

In April 1949, thanks to his son-in-law, Fr. Eugene quickly became part of the church life of Russian America. In 1950 he started organizing a new church named after the icon of the Mother of God, the Joy of All Who Sorrow, in a storefront in the city’s Northern Liberties section. At the same time, he worked diligently on getting U.S. visas for those in Schleisheim he’d promised to help. All together he succeeded in getting abut 500 families into the U.S. About 300 of them settled in Philadelphia. Although they had to start their lives from scratch, in tremendously difficult conditions, these Russian people sacrificed everything they could for the creation of their new church. The lion’s share of the work and responsibility lay squarely on the shoulders of the parish’s rector. Fr. Eugene literally built the new church with his own hands. Matushka Natalia worked at a factory and sewed vestments. Daughters Zoya and Irene worked at a factory and cleaned offices at night. All they’d earned was spent to help the new arrivals from Germany.

And so with the help of Our Lady, Fr. Eugene and his parishioners founded an Orthodox church in the American land.

Until 1980 Fr. Eugene served in this church, now in a small, fine stone-front building at 20th and Brandywine Streets. His activities, social as well as pastoral, earned recognition. The Union of the Struggle for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia petitioned the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR) to grant Fr. Eugene the mitre. That petition, supported by many others, was fulfilled.

On August 10, 1982, after a long illness, Fr. Eugene passed away. He is buried in the cemetery at Rova Farm in Jackson Township, New Jersey, where all his parishioners have been and still are buried. Matushka Natalia is also buried there.

The hero of this sketch was not marked by worldly fame, nor was he spoiled by honors and decorations. Fr. Eugene quietly performed good deeds, leading to Christ the souls of those thirsting for truth. Once he took the heavy cross of priesthood, he followed the Saviour and carried that cross to the end of his life. He bore his cross despite everything: the hatred of this world, the atheistic persecutions, the sorrows of those closest to him and national tragedy. Through all these trials he remained a priest and earned the name of “good shepherd.” That is why his life is a spiritual exploit.

— Based on “The Vestments of Light” by A.A. Kornilov