|

THE RUSSIAN YEARS

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna was born on 13 June (O.S. 1 June) 1882, in the Cottage Palace, Peterhof

Born on 13 June (O.S. 1 June), 1882, in the Cottage Palace, situated in the Alexandria Park at Peterhof, Olga was the youngest of six children of the Emperor Alexander III and the Empress Marie Feodorovna. Growing up, she spent much of her childhood in the family's 900 room palace at Gatchina, 40 miles (63 km) outside of St. Petersburg. Her father had been in power only a little over a year, having succeeded his father Alexander II, who had been murdered by a terrorist bomb while travelling along the Catherine Canal on 13 March (1 March OS), 1881. His assassins were brought to trial and hung for their vicious crime.

Olga with her parents and siblings. (Standing left to right) Nikolai (the future Emperor

Nicholas II),Georgy, Olga, Xenia,(Seated left to right) Empress Maria Alexandrovna,

Emperor Alexander Alexandrovich, Michael

Olga and her siblings, Nicholas (the future Emperor Nicholas II), born 1868; Georgy, born 1871; Xenia, born 1875; and Michael "Misha," born 1878, did not attend school, but were taught Russian and other languages [they were fluent in English, French and Danish], literature, mathematics, history, and art by various tutors within the confines of the palace. One other brother, Alexander, born in 1869, died in infancy. They had an English governess, Elizabeth "Nana" Franklin, whom Olga adored.

Grand Duchess Olga in happier times as a young girl in her beloved Russia

She considered her childhood years growing up at Gatchina as the happiest time of her life. She took a great interest in playing the violin and painting. Unlike many royal children, Olga and her siblings lived a modest, spartan life in which the strictest of discipline was required by their tutors, governesses, and parents. They slept on firm beds with hard, flat pillows and very narrow mattresses. A modest rug covered the floor. Straight-backed wicker chairs, the most ordinary of tables and bookshelves, needlework and toys, made up the only furnishings. A single precious object sat in one corner of their rooms: a silver-framed icon of the Blessed Mother of God, studded with pearls and other precious stones. Of all her siblings, she was closest to Michael or “Misha” as she preferred to call him. They spent hours running and playing from room to room and through the vast halls of the palace lined with priceless vases. It is generally believed that Olga had a strained and distant relationship with her mother for most of her life. On the other hand, she was very close to her father. They enjoyed their time together, taking walks and playing games in the vast Gatchina park, and sharing secrets. Olga was only 12 years old, when her father died suddenly in 1894. His death left the young grand duchess grief stricken, but she kept his memory alive by not forgetting what he had taught her: the simple way in which he preferred to live, care and respect for others, and appreciation for the natural beauty around her. Olga has been described as being indifferent to both dazzling jewellery and the strict etiquette that were symbolic of the Russian Court.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna & Duke Peter Alexandrovich, 1901

In August of 1901, she married Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg. Two years later, she attended a review of her brother Michael’s regiment at nearby Pavlovsk. It was there that she first set eyes on "God Apollo" as his fellow junior officers called him. Colonel Nikolai Kulikovsky, age 22, was a close friend of Michael’s and she persuaded her brother to seat her next to Nikolai during lunch, which he did. Before the meal was over Olga was in love. Soon after, Olga wanted to divorce Peter and marry Nikolai, but neither her husband, Peter, or her brother, Nicholas II would permit it. However, the marriage remained unconsummated, both Olga and Peter were unhappy, and was finally officially annulled in 1916 by Tsar Nicholas II.

On November 14, 1916, she married Nikolai Kulikovsky in the Church of St. Nicholas in Kiev. As a result of marrying a commoner, Grand Duchess Olga's descendants from her marriage to Nikolai were excluded from succession to the Russian throne.

The following year, the political atmosphere went from bad to worse in Russia and her brother abdicated on March 2, 1917. On August 12, 1917, Olga and Nikolai's first child, a son, Tihon, was born.

Less than a year later, on July 17, 1918, her brother, Nicholas and his family were brutally murdered by the Bolsheviks in the Ipatiev House at Ekaterinburg and the Romanov dynasty came to an end. The new regime headed by Vladimir Lenin placed a bounty on the heads of any surviving members of the Romanov family. Olga and Nikolai had to flee Russia shortly after their second son, Guri, was born on April 23, 1919.

Grand Duchess Olga, her husband, Nikolai Kulikovsky, and their two sons, Guri and Tihon

In 1920 they travelled by train to Novorossiysk and took shelter in the Danish Consulate. A month later, they went by ship to Dardanelles, a barge to the Island of Prinkipo, then on to Constantinople and Belgrade, where they met Regent Alexander Karageorgevich [later King Alexander I of Yugoslavia]. Her mother and sister, Xenia, went on a British ship to Malta and then on to England, where cousin King George V gave assistance. He was very supportive to Olga and her family during their exile in Denmark. In 1919, Marie took up residence at her summer villa, Hvidore, in Denmark. Olga was reunited with her mother on Good Friday, in the Amalienburg Palace in Copenhagen. Olga, Nikolai, and their two sons then went to live at Hvidore. Her mother, the last living Empress of all the Russias, passed away on October 13, 1928. After the death of her mother, the royal estate of Hvidore was sold and the Grand Duchess and her family were able to purchase with her portion of the inheritance Knudsminde Farm, several miles outside of Copenhagen, Denmark.

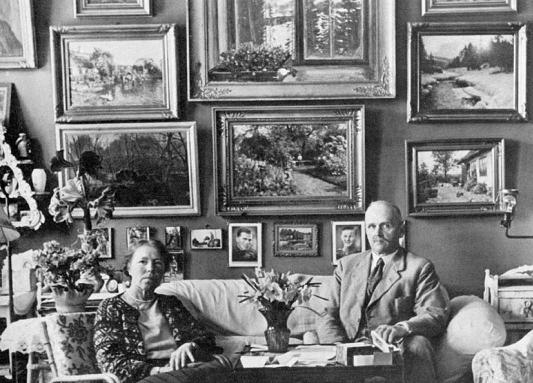

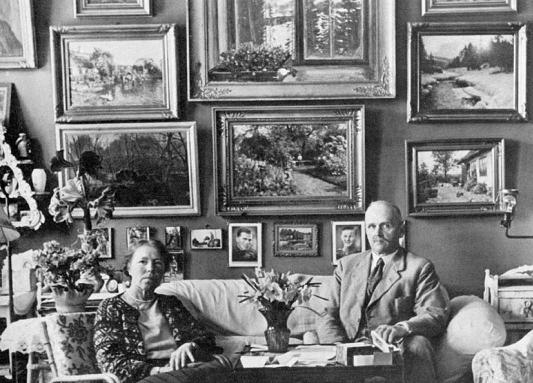

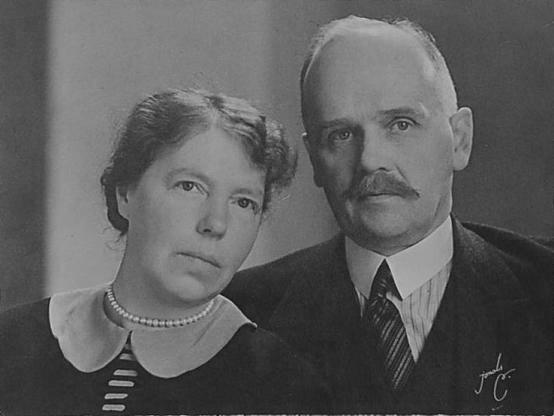

Olga and Nikolai at Knudsminde in the 1930s

Europe once again became a battlefield during World War II (1939-1945). Son Guri was married in May, 1940, and Tihon in April 1942. When Denmark was liberated on May 5, 1945, Olga and her family could not return to their homeland as they would most certainly be arrested and executed. Following World War II, Stalin's propaganda machine declared that Grand Duchess Olga had conspired with Germany against Russia during the war. In 1948, King Frederik IX could no longer guarantee their safety and Olga faced exile for the second time in her 66 years.

Her second cousin King George VI enquired about their finding asylum in Canada. Arrangements were made through A.H. Creighton, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway and District Superintendant of the Department of Immigration and Agriculture Development, for relocation to Canada. The Agent General for Ontario, Canada, J.S. Armstrong, stationed in England, handled the arrangements for the departure of the Russian Grand Duchess and her family to depart for the safety of rural Canada. In May 1948, the Kulikovskys travelled to London by Danish troopship. They were housed in a “grace and favour” apartment at Hampton Court Palace while arrangements were made for their journey to Canada as agricultural immigrants. On 2 June 1948, Olga, Nikolai, Tihon and his Danish-born wife Agnete, Guri and his Danish-born wife Ruth, Guri and Ruth's two children, Xenia and Leonid, and Olga's devoted companion and former maid Emilia Tenso ("Mimka") departed Liverpool for Canada on board the Empress of Canada. of eight to sail on the Empress of Canada, for their new adopted homeland.

THE CANADIAN YEARS

The Kulikovskys' arrive in Canada

They arrived in Montreal on June 10th and took a train to Union Station in Toronto. Their first night in Toronto was spent in a massive suite in the Royal York Hotel, but after two days Olga felt uncomfortable in such opulent accommodations and accepted an offer to stay with a local Russian family in their home.The Evening Telegram headline read: "Sister of Last of the Czars Arrives in Ontario to Farm." Creighton found them a 100 acre (40 ha) farm in Campbellville with a 10 room, two and a half storey red brick house for $14,000. They settled in with their sons, daughters-in-law, Agnete and Ruth, grandchildren, Leonid and Xenia, and 81 year old companion Mimka. With them were trunks filled with furniture, clothes, paintings, Faberge sculptures and picture frames, Marie’s traveling case and many other family mementos, and the jewels that Mimka had smuggled out of their house in Kiev and kept secure all those years.

After they were settled, Olga and her family became active members of the Toronto parish of the Russian Orthodox Church. They attended services at the Christ the Saviour Cathedral, which was then located at 4 Glen Morris Street [the cathedral moved to its present location at 823 Manning Avenue in the summer of 1966]. Together, Olga and Nikolai took a great interest in the well-being of both the church and its parish. Olga’s portrait hangs in the Cathedral, today, and her works as an artist embellish the beautiful interior iconostasis. She had created icons for the second level of iconostasis as well as the image of the Mother of God for the ancient (16th century) Greek “passage”, which was donated to the church by the management of Royal Ontario Museum. It was installed in the church on the right side from the altar (near the holy water tank). The main quality of Olga Alexandrovna was her attitude towards the people around her. Her unselfish kindness for everyone she met, her openness and welcoming heart were to leave a deep imprint in the memory of the parishioners of Christ the Saviour Cathedral. After her death in 1960, the parish school was named in her honour.

Grand Duchess Olga produced over 2,000 paintings in her life

Olga, who had painted since residing in Denmark in the 1930s, began to paint still life and landscapes in watercolours. In October 1951, she had a showing at the Eaton's Art Gallery, in Toronto, where her son, Tihon was employed. She produced over 2,000 paintings in her life. The sale of her paintings provided a source of income for her and her family. Works by Grand Duchess Olga are now in the private collections of HM Queen Elizabeth II, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh, HM King Harald of Norway, the Ballerup Museum, Denmark, and private collections in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Today, her paintings are highly sought after by collectors, each one fetching a hefty sum at auction.

By the end of 1951, Nikolai's health was failing and he could no longer manage the work the farm entailed. So they sold the farm to Wolfgang von Richthofen, a relative of the WWI German flying ace, the Red Baron. They moved to 2130 Camilla Road in Cooksville, a suburb of Toronto [now amalgamated into the city of Mississauga] in 1952. Neighbours and visitors to the region took interest in the rumours of the last surviving Romanov grand duchess living in Canada, and visited her often.

Grand Duchess Olga's modest home on Camilla Road still stands to this day

Their home was situated a half a mile (0.8 km) north of the thoroughfare named for King George's wife, Elizabeth, the Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW). The Grand Duchess became good friends with Colonel Thomas Kennedy and it has been said that he took good care of her during her later years. In 1954, when Olga's cousin Princess Marina of Kent [the daughter of Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia] came to visit, Camilla, a gravel road at the time, was paved from the QEW to Olga's driveway for the royal visitor's black limousine, which caused quite a stir in the neighbourhood. No doubt a lovely gesture from the Colonel.

Princess Marina of Kent was not the only royal who visited Grand Duchess Olga at her Cooksville home. Other royal guests included Princess Tatiana Konstantinovna of Russia, His Highness Prince Vassily Alexandrovich, Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, and his wife, Edwina Mountbatten, and Countess Mountbatten of Burma.

Grand Duchess Olga kept in touch with the Russian émigrés to the end of her life. Members of her old Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment [she had been appointed honourary Commander-in-Chief of the 12th Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment in 1901]. were now scattered all over the world, but she had not forgotten them. She had a remarkable memory and remembered many of the officers and men not only by their name and surname. In 1951, former officers and members of the famed Akhtyrsky Regiment gathered at her home to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Regiment. Thereafter, she became the patroness of the Association of Russian Cadets of Toronto.

By 1958, Nikolai was virtually paralysed, and on the morning of August 11, 1958, Olga woke to find that he had died in his sleep.

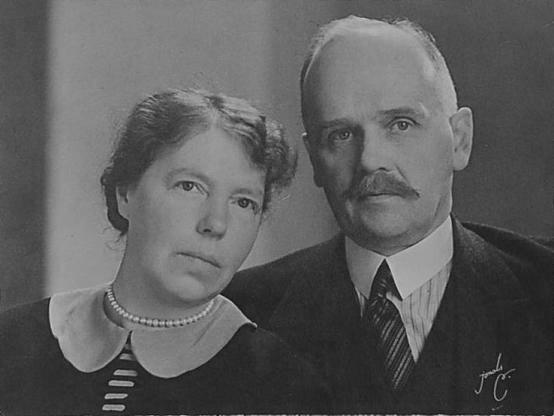

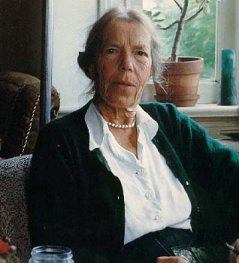

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and her beloved Nikolai

Prince Alexis Troubetzkoy spent the summer of 1959 in Hamilton, Ontario, where he had been commissioned as an officer with the Royal Canadian Navy (Reserve). He telephoned the Grand Duchess who graciously invited him to tea one Saturday afternoon. For days, he was nervous about meeting the youngest daughter of the Emperor Alexander III. When he arrived at her home, he walked up the driveway to her modest bungalow, grasping a bouquet of roses with perspiring hands. Nervously, he knocked on the door and was greeted by “a little old lady dressed in a scruffy, unpretentious dress”, whom he assumed was the maid.

“Is the Grand Duchess at home?” he asked in Russian.

“And what do you want with the Grand Duchess?” came the woman’s reply.

“Well, I have an appointment with her” he said, now somewhat irritated.

“Well”, said the woman gravely, looking at him with feigned suspicion, “I don’t know. . .”. She paused, flashed a warm smile, and threw her arms around him, exclaiming with delight, “I am she!”

Prince Troubetzkoy visited the Grand Duchess several times that summer. It was during this time that the St. Lawrence Seaway was officially opened. The Royal Yacht Britannia brought Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip to Canada. Olga, along with Tihon were invited to a private luncheon on board the Britannia, which was docked in the Toronto Harbour. Olga was King George V’s first cousin, and thus a cousin to both Elizabeth, and her sister, Margaret. She knew both sisters well when they were small children.

The following day, Prince Troubetzkoy called on the Grand Duchess to find out how things went and what her impressions of the royal luncheon were.

“Ah”, she said, “it was a cosy evening, and it was great fun to have seen Elizabeth once again, after these many, many years”. Eyes glistening and bubbling with excitement, the Grand Duchess went on to tell the details of the evening and to give impressions of the now grown-up Elizabeth. She spoke of the two sisters as small girls and she carried vivid memories of them, one of whom she found “considerably less serious and playful” and the other “pensive and perhaps a bit less warm”. The Grand Duchess commented on a table which stood in one of the salons; it was taken from the Russian Imperial Yacht Standart and presented to King George V for the Royal Yacht. She remembered it.

What impressed Prince Troubetzkoy most of all was that Grand Duchess Olga had not been forgotten by the Queen. At the time of the Revolution, Olga together with her mother, the Empress, and sister, Xenia, found themselves safe in Denmark. The Empress died there in 1928 and Xenia settled in England at Hampton Court, living under the protection of King George V in a “grace and favour” residence. Olga’s life, however, evolved considerably less comfortably. She was married to a commoner and the couple made their way to Canada to begin life afresh as farmers. At the time of Prince Troubetzkoy’s visits, Olga was already a widow. In the years that lapsed between her visits with the child Elizabeth, no substantive contact had been maintained between the Court and the exiled Grand Duchess. But, despite the many years which had lapsed, it was family once more.

Grace Fraser Hancock also remembers Grand Duchess Olga. In 2004, she recalls, “I met Grand Duchess Olga shortly after she moved across the street from us in Cooksville. She was a very proud lady. I remember that she hated hats, and the year she was going to visit Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, she had to buy a hat. So I took her to Dixie Plaza and we bought a pale blue hat. When she got home, she told me that as she was leaving the royal yacht, she tossed her hat into the lake. She always wore pearls. She said that you had to wear them all the time because the pearls absorbed the oil from your skin and gave them a lustre. She took in stray dogs and always took them for walks and she wore rubber boots without socks and her feet used to get blue, so I bought her a pair of workmen’s socks to wear.”

The simple apartment in Toronto's east end, where Grand Duchess Olga died on

November 24th, 1960. The building has survived to this day.

Grand Duchess Olga became ill in 1960 and was diagnosed with cancer. After a brief stay in the Toronto General Hospital, she was taken in by her friends, Colonel Konstantin and Galina Martemianoff, who lived at 716 Gerrard Street in Toronto's east end. Grace Fraser Hancock recalls, “I had heard that she was ill, so my friend Erma Large and I drove into Toronto to see her. She was living over a hairdressing salon. The lady she was staying with took us upstairs and she was lying on a small cot and she was very frail. We sat and talked to her for awhile and left.” Grand Duchess Olga died on November 24, 1960, in the tiny room of the Martemianoffs’ second floor flat with a picture of her husband by her side. This scenario gave rise to the rumour that Olga died penniless, but such was not the case.

The body of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna at the

Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Toronto, December 1960

On November 30, Grand Duchess Olga lay in state in Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Toronto. The Union Jack and Russian imperial standard hung from each corner of the platform where the coffin sat. Her funeral was attended by more than 500 mourners.Wreaths were sent by the king and queen of Denmark, the king of Norway and England' s Queen Elizabeth; imperial guardsmen from the 12th Hussars Ahtyrsky Regiment were the pallbearers. She was buried next to Nikolai, in the Russian Section of York Cemetary. The Grand Duchess' friend, Bishop John of San Francisco, sprinkled Russian earth on her grave. The Grand Duchess was the soul and the heart of the Toronto parish, and her death in 1960 created a void within the Russian community, leaving none of the parishioners untouched and felt by many as a personal tragedy.

After her death, her sons closed down her house on Camilla Road and sold it and all her possessions that she treasured from her days in Russia. Her estate was estimated to be worth around $200,000. The combined worth of the items that Olga managed to smuggle out of Russia in today's dollars would have been estimated at more than $1.2 million. Guri died in 1984 and Tihon in 1993.

Grand Duchess Olga's grave at York Cemetery in Toronto

A bronze plaque was unveiled on August 25, 1996, at her grave site in York Cemetery, in Toronto, in dedication of her memory, while more than 200 family members, friends and newsmen looked on. It is interesting to note, that Mimka, Olga’s devoted companion and former maid is buried in a simple grave nearby.

During her life in exile, Grand Duchess Olga never lived with any delusions of grandeur or dreams of a Romanov return to power. She lived a remarkable life, enduring more than her share of personal heartaches. She experienced an attempted assassination of her brother Nicholas in 1891, the death of her dear father in 1894, the death of her brother Georgy in 1899, a war between Russia and Japan between 1904-1905, adultery in 1906, a nervous breakdown in 1913, the death of her governess also in 1913, separation and divorce in 1916, serving as a nurse in an Army hospital in Kiev during World War I (1914-1918), an attempted assassination on her own life, a Revolution that brought an end not only to her brothers reign as Emperor, but also an end to the monarchy in her beloved homeland, exile from both Russia and Denmark, the murder of her brother Nicholas and his entire family in 1918, the death of her mother in 1928, and the death of her beloved husband, Nikolai in 1958. Her final tragedy was the cancer that took her life in 1960. Despite a lifetime of relentless tragedy that followed her during her 78 years, she endured each with noble fortitude. She was once and always, a Grand Duchess of Russia.

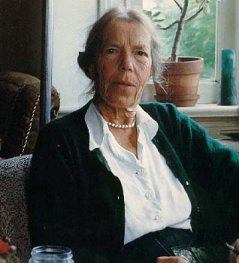

Olga Alexandrovna, once and always, a Grand Duchess of Russia.

A Note from the Author

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this article to ensure accuracy of names, places, events and dates. There is never a guarantee for such when writing about historical figures for various reasons. Quite often, information can be lost in translation. Dates in particular are always up for scrutiny, especially when researching the history of pre-Revolutionary Russia, which used the Old Style, Julian calendar [until February 1918], rather than the Gregorian calendar, which was used in the West. As a result, dates in the 19th century were 12 days behind those in Europe; in the 20th century, they were behind 13 days. In writing this article, however, I would like to point out that some sources used the dates from both the Julian or Gregorian calendars without specifying which was used in the context of their work. I have tried to use the dates according to the Gregorian calendar. If I have made any errors, I would greatly appreciate the reader bringing them to my attention [including their sources] so that the necessary correction can be made, thus ensuring as accurate a work as possible. ---Paul Gilbert

Sources

Bousfield, Arthur, et al. Royal Observations: Canadians and Royalty. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1991.

Kulikovsky, Paul, et al. 25 Chapters of My Life: The Memoirs of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. Kinloss: Librario, 2009.

N/A: Cooksville: Country to City, Part Four 1950-2000, Russia’s Last Grand Duchess. Mississauga: Private Printing, 2005

Phenix, Patricia. Olga Romanov: Russia’s Last Grand Duchess. Toronto: Viking/Penguin, 1999.

Vorres, Ian. The Last Grand Duchess: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. New York: Charles Scribner’s & Sons, 1964.

|