April 12, 1927, Philadelphia Athletics at New York Yankees

(Excerpt from my manuscript for the upcoming book “The 1927 Yankees: Anatomy of the Greatest”)

As was usual, hope sprung eternal for everyone on Opening Day. The beginning of the season meant a fresh start, with teams that finished in last place a year earlier on even ground and in the same position as teams that finished in first. Teams that had suffered through disappointing seasons, pennant races and even a seven-game world’s series had new life, and with optimism came chances for redemption.

Opening Day was certainly always special for the players. By the end of spring training, they were ready to get going. Even though a victory on Opening Day ultimately really didn’t mean a thing come September, let alone October, it was one of the best parts of the year, and one that was marked with enthusiasm and excitement.

For the Yankees, Opening Day in 1927 carried an even deeper meaning. It meant an opportunity to pick up and right a ship on the same field where they blew a three games-to-two lead in the ’26 World Series on a certain melancholy afternoon 184 days earlier.

Opening Day was also special for baseball fans. To them it meant an end to the off-season and the official beginning of great possibilities, as each fan held out new hope for their club’s chances.

The big parade toward Yankee Stadium started way before Noon, a full 3-½ hours before game time. Almost every rapid transit line in New York City led, or at least provided connection, to the stadium, and the travel time from 42nd Street in downtown Manhattan via the subway was only about 15 minutes. When the transit cars emerged from underground into the Bronx, the rails elevated just outside right field, which made the playing field slightly visible to the passengers inside as the train slowed a bit because of an almost immediate stop at 161st Street, a main artery that also featured a trolley. Two other “L” stations were within a quarter of a mile from the stadium, located at Sedgwick and Jerome Avenues, and coincidentally they also serviced the Polo Grounds terminal on the same line.

The subways, taxicabs and busses brought ever-increasing crowds into the Bronx. Since fans got out to the park early to gobble up any and all available tickets in droves, all signs pointed to the largest crowd to see a New York opener since Yankee Stadium was dedicated in ‘23. As baseball’s best, the stadium also happened to be among the grandest of all sporting venues in the land.

*

Approaching Yankee Stadium in 1927 could only inspire awe in an individual, for as big as it was, fully 75 feet high, it looked even bigger the closer one got. Outside the massive and attractive concrete facility, six freestanding ticket booths were in front of the main entrance, and upon the purchase of a ticket, fans could enter the enclosure without unnecessary delays.

Inside, spectators enjoyed three tiers of seating, unique in having a middle tier or “mezzanine floor” with seats, where the levels of the main grandstand seated 50,000 fans. Supported by vertical steel beams, it extended from behind home plate out to just past the infield in left, but unbalanced, it continued to the foul line in right field.

Each level of seating sloped downwards toward the playing field. They could be reached by broad ramps beginning at the main entrance that swept upward in a spiral fashion and in such a way that the climb wouldn’t be tiresome. All of the decks were entered from runways in the rear, where fans reached the seats through wide aisles that led straight down to the boxes or front rows, and each level offered an unobstructed view of the diamond and outfield. Adorning the top of the third deck was a distinctive, 16-foot copper façade, thus providing the stadium with an air of dignity.

The single deck down the third base line wrapped around the foul pole and extended into left field. Next, almost a million feet of Pacific Coast fir was used to build the wooden bleachers, which bordered the rest of the outfield. The approximately 70 rows of seats could hold another 15,000 fans and formed the northern barrier of the field, reachable through the gates that were nearest the subway.

Aside from the necessary support beams that barely interfered, there wasn’t a single seat in the entire stadium from which the entire playing field couldn’t be clearly seen. It would also be friendly to patrons, with an unheard of eight toilet rooms for both men and women strategically scattered throughout the stands and bleachers.

The playing field was asymmetrical and very deceiving. The outfield corners were extremely cozy and reachable for pull hitters, a mere 281 feet down the left field line and 295 feet down the opposite right field line, both of which had the required vertical white poles at the walls to help distinguish fair and foul balls, while the wall in right also had a three-foot wire fence. However, the walls curved away quickly to form the most outfield real estate in the majors. Moving panoramically from left to right, dimensions were 415 feet to straight away left field, 490 feet to the deepest region of left-center, appropriately nicknamed “Death Valley”, 487 feet to the wall in straightaway dead center field, 429 feet to the deepest part of right-center, and then 344 feet to right.

There was a red cinder warning track that encircled the outfield, the entire field for that matter was nearly a quarter of a mile long, and behind it was a gradually sloped bank upwards toward the center and right field bleachers, covered with grass. A flagpole sat on the grade in deep left-center, and it was in play.

White billboards adorned the base of the bleachers’ walls with “Ever-Ready sterilized shaving brushes” in left-center and “Gem razors” in right-center, an area whose occupant’s seats were often referred to as “Ruthville” and were protected by the wire fence. In back and above the bleachers in right-center there was a manually operated black scoreboard, which featured available space for 12 innings of line scores for every game in both major leagues. Then looking out past the sea of bleachers, whose back wall was also covered with advertisements in addition to the scoreboard, was a backdrop of buildings, most being located a block away on the Bronx’s Grand Concourse.

The pitching mound was connected to the home plate area with a dirt pathway. As was common, each white foul line was extended inward past home plate, which formed an “X” at the base of the pentagon. Then behind home, there was large area of 82 feet for a catcher to chase wild pitches, but scant real estate for fielders down the base lines in foul territory.

The Yankees’ dark green home dugout was on the third base side, and at the top of the steps was where the players’ bats were normally lined up. The clubhouse was behind their dugout, under the main level of the grandstand and level with the street, and a passageway ran between the two. Since the other dugout occupied the first base side, visiting players had to actually walk through the Yanks’ dugout and then across the field to their bench.

The stadium’s fancy bullpens were located in left-center in the open space between the stands, and under the bleachers, complete with a wooden bench. When the pitchers were out there, they had little idea what could be going on out on the field save for the fans’ cheers overhead. When personnel in the dugouts wanted to get in touch with the guys in the bullpen, there was a telephone. Even though it was out of sight, it amounted to a pretty modern bullpen.

While Ruppert maintained his office at his brewery, the Yankees’ executive offices had been moved from midtown Manhattan and were located between the main and mezzanine decks. An electric elevator connected them with the main entrance.

Since 1920, the club had drawn more than a million fans every year, save for the disappointing ’25 season. For ’27, Ruppert lowered the price of admission by 33 percent from 75 cents to 50 cents for all of the 22,000 bleacher seats, an especially good move early in the season when the uncovered seats could be warmed by the sun to offset some cold. The seats in the grandstands sold for $1.10. But baseball attendance revenue wasn’t Ruppert’s only source of income at Yankee Stadium.

Other sporting events had also been held within the confines of the Stadium. In fact, underneath second base was a 15-foot deep brick-lined vault that contained electrical, telephone and miscellaneous connections for a boxing ring and other events. Beginning in May 1923, to date the stadium had hosted seven different fight nights that encompassed half a dozen title bouts at various weight classes.

Three months earlier, back on January 20, 1927, boxing promoter extraordinaire George “Tex” Rickard and Colonel Ruppert signed a lease that provided Rickard exclusive use of the stadium, “for the conduct of wrestling, sparring and boxing matches and exhibitions”. In return, Ruppert and the Yankees were to receive 10 percent of the gross receipts, which effectively made Ruppert and Rickard partners.

It was Rickard that had an eye towards bringing a possible Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney rematch to New York, the former being the very popular heavyweight champion who lost his long-standing title to the latter in September of ’26 in Philadelphia. Rickard came up with an idea of elimination bouts to determine Tunney’s next opponent, and the survivor would challenge Dempsey for a chance at Tunney in September 1927. Rickard also held out hope that enough pressure could be applied to the New York state boxing commission to grant a license and raise the ticket ceiling prices for a larger payday.

Collegiate football had also been played on the field at Yankee Stadium. With the first game in October 1923, 15 different gridiron games had been contested, with New York University, occupants as their home field in ’26, involved in eight of them that yielded a 6-2 record. The stadium also provided the setting for the last two notable and high profile Army-Notre Dame clashes, with one game going each way. And last but not least, the professional ranks had just started playing football at Yankee Stadium in ’26.

Regardless of where Ruppert’s revenue came from, he spent lavishly, but wisely, for his talented baseball team. The Yankees entered the 1927 season with the highest payroll in baseball, a sum that was a little over $258,000. With 25 primary players on the roster, it put the average salary of a Yankee at about $10,300 annually, reflective of both the players’ ability and their stature in the profession. It amounted to approximately $3,000 more than the average baseball player, and was almost eight times what the average American family earned. Even without Ruth’s monster salary, the average was still about $1,000 more than the typical player, a healthy $8,000, and even this was more than six times the annual household income. It certainly paid to be a Yankee. And in charge of all of it, Miller Huggins received a reported $37,500 as the manager.

*

The throng not only flocked into the Bronx to see the Yankees begin the season, but also for the first time in six years their opponent would be none other than the Athletics. Since the game pitted the American League’s two strongest teams, it was easily the marquee match-up of the day, not only in the junior circuit but all over major league baseball as well.

On one side there was the defending American League champions. On the other side there was Philadelphia, and it certainly was no secret that they had a first-rate offense, defense and pitching, which is why the pundits made them the junior circuit’s favorite in ’27.

With the nice blend of youth and veteran experience, the Athletics in 1927 were viewed as a very formidable team. Practically every weak spot had been filled, and no team appeared more fortified for emergencies with two top-notch performers at every infield position. Adding it all up, it was easy to see why coming out of spring training they were one of the favorites for the American League pennant. After annexing four out of five recent exhibition games from their cross-town brethren Phillies to take the Philadelphia city title, the Mackmen were ready for the season.

Unfortunately, the Athletics somehow always seemed to come up short against the Yankees under Huggins. In nine years of head-to-head competition overall, the Mite Manager had won 125 games against the league’s senior pilot, taking each of the first seven seasons’ series, while Mack could only mark less than half that amount on his side of the ledger, 59 victories. Moreover, since Ruth joined the club, New York enjoyed more success against the Athletics than any other team in the league, a coincidence attributed more to bad Philadelphia teams than to the Babe’s prodigious hitting. However, Mack had increased his number of victories in the series each and every year in the 1920s. It culminated in identical 13-9 records against Huggins each of the last two years, the Tall Tactician’s first decisive marks in the rivalry.

Winning a game at Yankee Stadium was extremely difficult for any visitor. In the four years of its existence, the Yanks had yet to post a losing record in any given season, even the dismal ‘25 campaign, and they owned a cumulative 183-123 mark, good for a .598 winning percentage. Mack’s crew fell well within those parameters, as he had not had a winning yearly visit in the Bronx, and his teams only won 18 of 44 games.

The Athletics had also performed with mediocrity on opening days since the junior circuit was formed. In their 26 games, they had posted only a 12-14 record. Unfortunately, they had also faced some of the game’s best pitchers. Up against Washington’s Johnson seven times, they beat him only twice, and against a young Boston lefty named Ruth, the Athletics had lost both, in ‘16 and ‘18.

For New York in their 24 season openers, they owned an overall record of 13-10-1, the tie coming in 1910, and they had won their last four straight. Adding up all of the available statistics, even the casual fan would have to concede that the scale swayed sharply towards a Yankees’ victory.

Huggins had a slew of available experienced hurlers from which to choose, and four had prior Opening Day experience, not counting the Babe. Bob Shawkey had four opening game assignments under his belt (‘20, ’23, ’24, and ’26), all with New York. Urban Shocker had started five, with the first four coming as a member of the Browns (1921-24) and another in ’25 with the Yanks. Dutch Ruether also had five, with all of his starts of the senior circuit variety, twice with the Reds (’19 and ’20), and three more in Brooklyn (1922-24). Finally, Herb Pennock had been chosen by none other than Mack to open the ’15 season for the Athletics.

Despite the slew of available pitchers with impressive credentials, Huggins opted for Waite Hoyt to face the Athletics. It would be the first Opening Day start of his career, and it made him New York’s 15th different pitcher to start an opener.

Word came earlier in the day that Johnny Sylvester would not attend Opening Day at Yankee Stadium. He was the now 12-year-old from Essex Falls, N.J. whose serious illness during the ’26 world’s series had led Ruth to send him autographed baseballs from St. Louis and then visit him in his home after the Yanks’ series loss, gestures that doctors credited as life saving. The publicity surrounding the gesture also garnered the boy presents from two other major sports heroes, an autographed football from professional star Red Grange and an autographed tennis racquet from “Big” Bill Tilden. Even though Johnny had since recuperated enough over the ensuing months to attend school, his parents believed a trip to Yankee Stadium in the cold weather could prove a setback, and school won out. But just as Johnny had done the previous October, he could sit by the radio and tune in after school.

While there would be no radio broadcast schedule of the Yankees’ regular season home games in ’27, as it was thought to detract from gate attendance, the front office made a lone exception for the opener. Graham McNamee of WEAF based in New York would do the play-by-play for both his station and WJZ radio beginning at 2:45 p.m., a full 45 minutes prior to the first pitch.

McNamee was easily the most famous sports broadcaster in the country. Millions knew his voice through his various descriptions of different sporting events, including the 1926 World Series and most recently college football’s Rose Bowl on New Years Day. He had even written a book entitled You’re on the Air that was published in ’25 by Harper and Brothers.

Chicago was considered one of the pioneers in broadcasting, and they did so with games for a few years. Others also toyed with the idea of announcing a good portion of their games over the waves in ‘27, a group that included Boston, Detroit and St. Louis.

In the Bronx, the home team came out from their third base dugout, with more than half a dozen new players proudly wearing Yankee uniforms, their trademark home white attire with vertical navy blue pinstripes. They wore v-neck flannel shirts with a brief tapered extension around the neck, and sleeves that extended over the elbows, although many players chose to cut and sew them above the elbow. The pants were “knickers”, worn just below the knees, and they were complimented with solid navy blue stirrups. Manufactured by Spalding and tagged as such in the inside rear collar of the shirt, each respective player’s name was chain stitched in red thread inside the rear collar and inside the rear waist in the paints, last name first with initials, such as “Ruth G H”. Rounding out the uniform was a solid navy blue wool cap that featured a white interlocking “NY”.

The “NY” insignia first made its appearance on the franchise’s uniforms when they were the Highlanders in ’09. Louis B. Tiffany had actually designed the interlocking letters in 1877 for a medal to be given to the first New York City policeman shot in the line of duty. One of the club’s original co-owners, Bill Devery, was himself a former police chief, and he adopted the insignia for use on both the cap and on the uniform jersey’s left sleeve.

The team donned pinstriped uniforms for the first time during the 1912 season and the insignia was moved to the left chest of the jersey, where it remained the following year even though pinstripes were gone and the club became known as the Yankees. When Tillinghast Huston and Jacob Ruppert purchased the club, pinstripes reemerged for their inaugural ’15 season as owners. Two years later the insignia was removed from the jerseys, which left the Yanks to wear plain and undecorated pinstripes for the next 10 years. All the while, the “NY” insignia remained on the hats, which variously had changed from solid navy to pinstriped, but ever since ’22 the club wore exclusively navy hats.

The Athletics were decked out in their road gray uniforms, with a “White Elephant” emblem outlined in blue stitching onto the front left chest. The metaphor was popularized after Giants manager John McGraw told the press that Philadelphia businessman Ben Shibe had “bought himself a white elephant” by acquiring the Athletics baseball team in 1901. Mack subsequently selected the white elephant as the team symbol and mascot, and instead of wearing an “A” on the chest as they had in their first 19 seasons, the Athletics went to the elephant emblem in ’20 and had been wearing it ever since. They also wore white stirrups with a thick blue stripe near the top. On their heads, the main panels of their caps were white outlined in blue, and featured blue bills.

Prior to the game, a backstop was wheeled behind home plate for batting practice, and various pitchers threw. As usual, when the Babe stepped in, almost everyone in the stadium, fans and players alike, stopped what they were doing to watch.

Before ever having to face Ruth in warm-up, six of the Yankees’ current staff had been victimized with long balls in league competition, which accounted for 19 of his career round-trippers. While playing for Boston, the Babe had smacked three homers off Shawkey during the ‘19 season, and belted a pair off Shocker to boot. Since moving on to Gotham, Ruth had smacked six more off the latter during his Browns’ stint, for a total of eight. Pennock was second on the list, having yielded five Ruthian shots while a member of the Red Sox pitching staff, including a pair in a June 25, 1920 game. And three others all had their names on the Babe’s personal list having surrendered one apiece, Joe Giard, Hoyt and Ruether.

In batting practice, Pennock threw first to show his teammates a southpaw’s look. Ruth hooked three of his offerings into the right field bleachers. A bit later when rookie Wilcy Moore worked on the mound, the bombardment of the bleachers off the Babe’s bat continued.

As was customary with big events, the photographers were all over to record it. During the batting sessions, Ruth posed with Cobb as the two compared bats, but baseball’s two greatest names hadn’t been nearly as friendly as the scene may suggest.

Cobb had personified the dead-ball era and “inside style” of bunting, taking extra bases and stealing that the Babe’s home run hitting made obsolete. Moreover, Ty greatly resented Ruth’s national ascension, which forced him to play second fiddle. Most of the fans preferred the excitement of the home run, and even in Cobb’s own home city of Detroit, they came out in droves to watch the visiting slugger instead of their own.

As the Babe’s popularity grew, Cobb became increasingly hateful of the younger challenger, for he saw Ruth not only as a threat to his style of play, but also to his style of life. While Cobb preached ascetic self-denial, the Babe had gorged on hot dogs, booze and women. But perhaps what angered Ty the most was that despite Ruth’s total disregard for his physical condition and traditional baseball, he was still an overwhelming success and brought fans to the ballparks in record numbers. As such, there was a lot of bad blood between the two players, and the Cobb-Ruth rivalry was understandable.

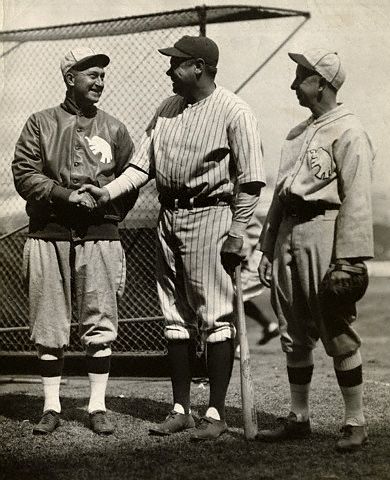

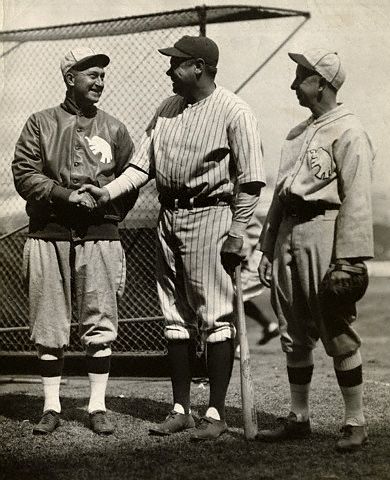

The pair of star players were also shot by the photographers with Eddie Collins, who entered the league a year after Cobb, while Ruth was still tossing a ball on the playground at St. Mary’s.

Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth and Eddie Collins

The Babe, whose diminished waistline was being recorded for posterity, had even found time to sit behind the microphone with McNamee.

The most interesting documentation of the day was probably a photo of the two managers. It showed Mack’s head towering over Huggins while standing next to him, laughing all the way.

Mack’s lineup card featured four newcomers and among them was a pair of touted rookies making their major league debuts, one at shortstop and one at first base. As for the latter, for the Athletics to seriously contend somebody had to step up as the everyday first baseman.

Huggins’ lineup card officially unveiled their revamped batting order. During most of the 1926 season, switch-hitting shortstop Mark Koenig batted lead off and centerfielder Earle Combs was second, and for most of the season Hug had first baseman Lou Gehrig batting third, Ruth fourth and in right field, and left fielder Bob Meusel hitting fifth. But during the important September series in Cleveland, and after dropping three straight games, Huggins flipped Combs and Koenig, dropped Gehrig to fifth, and moved Ruth and Meusel up to third and fourth, which was the same order the Mite Manager used in the World Series against the Cardinals. Now, the only change from that order for ’27 was that Huggins switched Gehrig into the cleanup slot and Meusel was right behind him in the heart of the order, having been relegated to fifth since his first appearance in the spring. His acting partner in the hit motion picture Slide, Kelly, Slide, which was completing its third week of showings at the Embassy Theater on Broadway and 46th Street, second baseman Tony Lazzeri, followed in the sixth spot, while the bottom of the order found third baseman Joe Dugan batting seventh and then the battery, catcher John Grabowski and Hoyt.

The largest Opening Day crowd ever, an unofficial attendance of 73,206 fans, packed Yankee Stadium solid. Rows of men were standing in back of the seats and along the runways, and care had to be taken about overloading the stadium to comply with fire and police rules. The Yanks’ management could easily have sold many more tickets for the standing room, but it just wouldn’t have been safe.

Also in attendance was nine-year-old “Little Ray” Kelly. Ruth had reputedly discovered the toddler playing catch with his father in a park along Riverside Drive back in 1921, and the famous slugger asked the elder Kelly if it was alright if the kid could join him at the Polo Grounds as his personal mascot, to which the answer was “yes”. Ever since, “Little Ray” was a fixture as the Babe’s personal good luck charm, attending most Yankee home games and sitting on the bench in the dugout, all without objection from the rest of the Yankee players. Included was Kelly’s well-documented appearance in full uniform for the ‘23 grand opening of Yankee Stadium, where he posed several times with Ruth for the photographers.

Manning the Yankees’ lumberyard was Eddie Bennett’s responsibility, the team’s hunchbacked mascot and batboy for seven years. A native New Yorker, he was also viewed somewhat as a good luck charm. Eddie was originally a Chicago White Sox mascot in 1919, winning the pennant during that scandalous year before joining the Brooklyn Robins for their ‘20 banner season. The following year, he was hired by the Yanks, and so began their string of flags.

Rounding out some others that took care of the Yankees was Fred Logan, who was charged with the clubhouse operation. Another was Michael “Pete” Sheehy from Yorkville, who while standing outside the Yankee clubhouse as a 15-year-old one summer day in ’26 was invited in by Logan to help out in exchange for admission. After it happened again, Sheehy stuck around, not only that day but also every day since as an assistant. Though he didn’t see entire games anymore, he did dart to the dugout to catch occasional innings every once in a while.

It was once said “you can’t tell the players without a scorecard”. At Yankee Stadium, the scorecards cost a nickel and they numbered the players in a list even though the players didn’t wear numbers on their uniforms. They were listed in the pre-printed card according to their logical spot in the batting order, so if a fan had to make a change, they merely crossed out the name and penciled in the replacement.

Both the Athletics and Yankees walked out to center field where the American flag was raised. In addition, up the pole also went the 1926 league pennant, all white with blue and red lettering, to fling around the breeze amid noisy cheers. Then the Seventh Regiment Band played The Star Spangled Banner.

Afterwards, Jimmy Walker was front and center, New York’s popular and charismatic “people’s mayor”. Though he was best known for his surprising rise within the powerful Tammany political organization, he also personified the rebellious attitude of Prohibition America.

*

In 1925, first Walker upset incumbent Mayor John “Red Mike” Hylan for the Democratic nomination, who had publicly accused none other than Arnold Rothstein as being the “big gambler” that backed Walker. Then after a tough campaign, in the fall he thoroughly trounced Republican candidate Frank Waterman, a vocal critic of Tammany’s mismanagement of municipal affairs, to enter the Office of the Mayor.

Everyone knew that Walker was a party loyalist who happily looked the other way on the city’s illegal liquor bootlegging industry. Moreover, despite being married, the dapper mayor also had a well-known fondness for Broadway’s chorus girls. But among the city’s working class, it was almost like Walker could do no wrong.

*

The mayor threw out the first pitch to Grabowski, but then came a few more pitches afterwards for the photographers. With all of the festivities finished, and with other notables and socialites showing up fashionably late, the season was ready to open.

Leading off for the Athletics, Collins stepped to the plate, spat on his hands, and rapped each shoe in turn with his bat. Grabowski crouched down, and the game was now in the hands of the umpire.

At Yankee Stadium, three umpires were assigned. Working home plate to call the balls and strikes was the respected veteran, William G. “Billy” Evans, a college-educated man who in 1906 became the youngest major league umpire in history at the tender age of 22. Known as a particular dresser, he had set the standard for an umpire’s appearance on the field, and also went on to earn a reputation for integrity and fairness.

Working with Evans was George Hildebrand, a veteran of 17 major league seasons, and Bill McGowan, in his third year, on the bases. Evans yelled “Play Ball!” and the game was on.

Getting down to actually playing the regular season and looking over at the Yankees’ coup revealed that Huggins had but a few rules, though he rigidly enforced them. One was that when the team was at home, the players had to report to Yankee Stadium at 10 o’clock in the morning to sign in on the day of a game. A couple of his other edicts were no smoking in uniform and no golfing except on Sundays and off days. Still another had served him well, and it was the most appropriate at the start of the game.

Hug was almost like a schoolmaster in the dugout during games. He insisted on no goofing around by the players, especially the reserves not in the starting lineup. Instead, they were all expected to sit on the bench, talk of nothing but baseball, and pay attention to the game to keep close track of the specific details, not only the score and the number of outs but also the count on any given batter. It was a well-known practice that Huggins might spring a pop quiz at any moment to ask a player what the given situation was, and it was better if they knew the answer.

Later in the first inning, Cobb stepped up and batted third, which marked his first appearance in a regular season game wearing a major league uniform other than Detroit’s. He was anything but over the hill, having batted .339 a year earlier in 79 games, and amazingly, had struck out only twice in 233 at bats.

When taking his stance at the plate, Cobb crouched slightly and held the bat low, his hands near his belt to slap at the ball. He did not grip the bat at the very end, instead he choked up and left an inch or two, and he also had his hands separated by the same type of distance. Cobb’s logic was that it provided balance and control of the bat and it kept his hands from interfering with each other during a swing. Such was the way a contact hitter approached the game.

Anyway, there was really nothing doing in terms of action. Hoyt sat down the Athletics with a scoreless first, much to the delight of the massive crowd.

In the home half of the first, Combs, who batted .298 in the spring games on 14 hits, led off against Grove and did what he was supposed to do when he got on base via an error. When Koenig promptly dropped down a sacrifice, the Kentucky Colonel made his way over to third base, at which point Ruth came to bat in front of the home crowd.

About the same time, out of nowhere appeared a man without his derby, and headed towards the plate. Mayor Walker quickly jumped over the rail and also headed towards the plate, and the Babe looked on rather quizzically. Interrupting the game to a slight array of boo’s, Walker shook hands with Ruth and then presented him with a silver loving cup for being chosen the most popular player by William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper faction. The diversion finished after a brief few minutes, Bennett shouldered the gift and took it away, and the Babe could get back to business.

On Opening Day and in the first battle, it was power against power with Ruth against Grove. The Babe and his various pitching adversaries usually squared off like two gunslingers standing all alone in the bare streets of a remote western town back in days of yesteryear. When he was up at the plate, Ruth wasn’t afraid to strike out and he swung with everything he had, going for it all on every pitch. Fans attentively looked on in anticipation of the figurative failing of either man, whether it be the Babe swinging powerfully but missing a third strike and twisting himself into a pretzel shape or the pitcher standing despondently alone as a Ruthian blow sailed out of sight before he made his triumphant tour of the bases.

Ruth was known for being a top performer in season openers. In nine of them he had fashioned an impressive .412 batting average on 14 hits in 34 at bats, with four doubles and two home runs. Included in his past performances were a perfect five-for-five day with a pair of doubles in 1921 during an 11-1 victory over the Athletics at the Polo Grounds, two years later the Babe highlighted the opening of Yankee Stadium with a three-run homer during a 4-1 win over the Red Sox, and as recently as ’26 he went three-for-six with a pair of doubles in a 12-11 victory in Boston. As usual, as he went, so did his team, and when Ruth played his teams had posted an impressive 8-1 record in openers.

In ’27, the Babe was very eager for his first duel with Grove, for he had never hit a home run off the southpaw. Such a streak wouldn’t end in this at bat though, because Lefty emerged victorious when he fanned the mighty Ruth on four pitches.

Another rather significant moment came in the home half of the second inning, when Lazzeri came to bat. It marked the first time he stood at the Yankee Stadium plate since that miserable but memorable October day. This time around he didn’t strikeout, but he did pop out to third baseman Sammy Hale.

The game still scoreless in the top of the third, Hoyt faced his mound mate. Grove was one of the worst hitting pitchers in the league. In his first two years his batting record showed 148 official at bats with just 16 hits, good for a paltry .110 average. Additionally, almost half of the time Lefty struck out, posting an astounding 68 whiffs to his ledger. Predictably, Hoyt retired Grove easily to preserve his shutout.

The two pitchers matched each other’s best for three frames, but Grove started to soften in the fourth when Koenig tapped in front of the plate, Lefty fielded the ball, and then he fired it to the fence in right for an error. The Yankees had a runner on third and their best scoring opportunity yet. Ruth followed, and in this dramatic moment could do nothing more than loft a high infield pop up to second. Gehrig was next, and he walked down to first. After Meusel hit back to the mound, the inning ended with Koenig being run down, and the Athletics avoided any damage.

When another Philadelphia scoreless fifth followed, Dugan led off the home half. He plopped a ball into right field that Cobb came stumbling in just a half-stride too slow to field, and it went for a single. After Grabowski walked, it appeared that the Yanks might finally be able to solve Grove. Hoyt laid down a sacrifice bunt towards first, but Branom made a freshman mistake when he dropped the ball as he started to throw for the lead runner at third.

With the sacks fully occupied, no outs and the top of the order coming up, the Yankees had Grove on the ropes. However, it must be pointed out that if Cobb had been a little faster, Grove had a little more control and Branom had been more sure-handed, there would be no predicament. The old saying had it that baseball was a game of inches, and in this particular inning in the Bronx, it sure was.

Combs didn’t benefit from any small measurement when he promptly smacked a double over leftfielder Bill Lamar’s head to plate the season’s first runs and give the Hugmen a 2-0 lead. When Koenig grounded out, Hoyt stayed anchored to third. With mates on second and third, Ruth gave it three hearty swings and struck out again, much to the crowd’s dismay. Gehrig then smacked a grounder towards Collins at second, and when the ball took a bad hop right through his spread legs and rolled for a scratch double, it scored both Hoyt and the speedy Combs, which gave the hometown boys four runs on just three hits.

The way Hoyt was pitching, four runs looked pretty solid. However, there was still half a game left as they moved to the sixth inning.

Cobb personally led the Philadelphia attack in the sixth and flashed signs of his old self when he beat out a perfect bunt. Standing on first base, and the owner of a record 865 career stolen bases, it was very possible that Ty would take off for second.

It was an important part of the psychological warfare that made Cobb the player that he was. He had always been a quick thinker, and the Georgia Peach liked to believe that it was his constant threat to do anything and everything on the base paths that would disrupt pitching batteries and infielders by upsetting their concentration. It was one of the little things that Cobb had done throughout the years, getting his opponents to think that he knew more than they did, that many times gave him an advantage.

After Simmons’ out, a short single by Hale sent Cobb racing over to third base where he slid cleverly under Combs’ throw to Dugan, conjuring up memories of old time, station-to-station baseball. Ty then scored the first run of the year for his new team as Lazzeri threw out Branom. Hale also came around and scored when Gehrig muffed a throw to first, and it cut the New York lead in half, 4-2.

In the home half, the Yankees immediately set about to answer when Lazzeri opened the frame with a double over the heads of both Cobb and Simmons in right-center. Dugan’s bunt moved Tony up to second, and he then scored on Grabowski’s single to left. Hoyt moved his battery mate up with a sacrifice, and Johnny scored when heralded frosh Boley, previously known in the minors as an exceptional fielder, failed to gather Combs’ grounder to short, which upped the count to 6-2. When Koenig tripled to deep center, it easily fetched Combs with another run.

Once again it was the Babe’s turn to bat, but instead of the big slugger strolling to the plate it was Ben Paschal taking his place. By reason of explanation, Ruth was removed suffering from a bilious attack, out “with a slight cold and fever” after striking out twice with men on base and popping out. Paschal, who two years earlier on Opening Day had a great game with a home run while the Babe was in a hospital bed, made good on his first action of the ’27 season when he slung a single into right, and Koenig scored to make it an 8-2 game.

The latest outburst sent Grove to the showers after the frame ended. Mack summoned Jack Quinn from the bullpen, who, at age 43, was the oldest player in the majors and one of a few pitchers still legally permitted to throw a spitball. A veteran of 14 major league seasons, plus another two in the Federal League, Quinn actually had two tours of duty with the New Yorkers, a Highlander from 1909-12 and a Yankee from ’19-’21.

The old pitcher did his job in the home half of the seventh. Unfortunately, he and his teammates were running out of time.

The eight runs were about all the Yankees would need, but the Athletics did manage to tally another run off Hoyt in the eighth. With one out, Simmons doubled inside third base and scored on Hale’s single, and he attempted to stretch the scratch into a double but should have known better than to challenge Meusel’s strong and accurate arm, a bullet that nailed Sammy at second.

Two straight Athletics openers had gone into extra innings, but for a third to do the same, the club had some ground to make up. In the top of the ninth, none other than Zack Wheat was sent to bat for the pitcher. It pitted the former Brooklyn star up against the former Brooklyn Schoolboy.

*

Wheat was a veteran of 18 National League seasons with the Dodgers, most recently referred to as the Robins. He had been a fan favorite as the club’s clean-up hitter and left fielder, possibly the most popular player to ever wear a Brooklyn uniform, and owned almost all of the franchise’s offensive records.

Wheat used his smooth left-handed stroke to become the senior circuit’s batting champ in 1918 with a .335 average, and he hit better than .300 in 13 different campaigns. Possessing decent power, he hit 60 home runs in his first 12 seasons before he adjusted nicely to the lively ball era with 71 homers from 1921-26, and his 131 long balls ranked sixth on baseball’s all-time career home run list. During that six-year power surge, Wheat also collected his first three 200-hit seasons in ’22, ’24 and ’25, and posted a career-high batting average of .375 in both ’23 and ’24. However, after three straight years batting above .350 his average dipped to .290 in ’26, and many accused the star of not hustling. Given the combination, the Robins released Wheat on New Year’s Day.

He turned down an offer to play with the Giants to join the Athletics, reputedly with Connie Mack’s promise of regular playing time. Unfortunately, when Cobb became available a few weeks later, he matriculated to Philadelphia to make an already crowded outfield even more crowded. It left Wheat the odd man out in a five-man outfield.

*

The former Brooklyn star received a polite New York applause as he stepped in at Yankee Stadium, then Wheat promptly singled. He was allowed to steal second, but teammates Collins and Lamar could not budge him any further, and the game ended with Cobb in the on deck circle.

After they got started, the Yankees had no trouble shaking away the bad memories that lingered from the previous October. They stroked 10 hits, with four going for extra bases and Dugan’s three singles leading the safeties, and behind Hoyt, who pitched smoothly all the way and had first-rate support, the Yanks pounded preseason favorite Philadelphia and their ace hurler, 8-3.

It was New York’s fifth consecutive win in a season opener, and it raised their record against the Mackmen in nine openers to 5-1. While all of that was nice, it was this win that was particularly satisfying.

The Hugmen had officially just served notice to their chief competitor, and for that matter, the rest of the league. If it was any indication of things to come, the next 21 scheduled games between the Athletics and Yankees were sure to be watched closely.

The New York Times newspaper was 76 years old and had begun to call itself “the paper of record” to entice libraries into archiving it. In attendance and covering the game for the paper was James Harrison, who penned his report with, “The jury brought in its verdict…Baseball, harassed and beclouded by the scandals and semi-scandals of last winter, found vindication.”

Fred Lieb of the New York Post was also in attendance, and he scribbled his thoughts. “Waite Hoyt, the Brooklyn mortician, made a neat job of burying the opening day hopes of the Athletics…We regret to say that our good friend, the Bambino, was the ‘bust’ of the opening day party.”

Though Johnny Sylvester couldn’t attend the game, he did listen to it over the radio. Afterwards, the Babe called the youngster on the phone and offered that he would visit him within a few days.

Return to The Unofficial 1927 Yankees Home Page

Email: jeffrey.linkowski@verizon.net