![]()

![]() Pascal Variables

Pascal Variables

Variables store values and information. They allow programs to perform calculations and store data for later retrieval. Variables store numbers, names, text messages, etc.

Pascal supports FOUR standard variable types, which are

![]() integer

integer

Integer variables store whole numbers, ie, no decimal places. Examples of integer variables are,

34 6458 -90 0 1112

![]() char

char

Character variables hold any valid character which is typed from the keyboard, ie digits, letters, punctuation, special symbols etc. Examples of characters are,

XYZ 0ABC SAM_SAID.GET;LOST [ ] { } = + \ | % ( ) * $

![]() boolean

boolean

Boolean variables, also called logical variables, can only have one of two possible states, true or false.

![]() real

real

Real variables are positive or negative numbers which include decimal places. Examples are,

34.265 -3.55 0.0 35.997E+11

Here, the symbol E stands for 'times 10 to the power of' Types integer, char and boolean are called ORDINAL types

Using Pascal VARIABLES in a program

The basic format for declaring variables is,

var name : type;

where name is the name of the variable being declared, and type is one of the recognised data types for pascal.

Before any variables are used, they are declared (made known to the program). This occurs after the program heading, and before the keyword begin, eg,

program VARIABLESINTRO (output);

var number1: integer;

number2: integer;

number3: integer;

begin

number1 := 34; { this makes number1 equal to 34 }

number2 := 43; { this makes number2 equal to 43 }

number3 := number1 + number2;

writeln( number1, ' + ', number2, ' = ', number3 )

end.

The above program declares three integers, number1, number2 and number3.To declare a variable, first write the variable name, followed by a colon, then the variable type (int real etc). Variables of the same type can be declared on the same line, ie, the declaration of the three integers in the previous program

var number1: integer;

number2: integer;

number3:integer;

could've been declared as follows,

var number1, number2, number3 : integer;

Each variable is seperated by a comma, the colon signifies there is no more variable names, then follows the data type to which the variables belong, and finally the trusty semi-colon to mark the end of the line.

Some example of variable declarations

program VARIABLESINTRO2 (output);

var number1: integer;

letter : char;

money : real;

begin

number1 := 34;

letter := 'Z';

money := 32.345;

writeln( "number1 is ", number1 );

writeln( "letter is ", letter );

writeln( "money is ", money )

end.

![]() VARIABLE

NAMES

VARIABLE

NAMES

Variable names are a maximum of 32 alphanumeric characters. Some Pascal versions only recognise the first eight characters. The first letter of the data name must be ALPHABETIC (ie A to Z ). Lowercase characters ( a to z ) are treated as uppercase. Examples of variable names are,

RATE_OF_PAY HOURS_WORKED B41 X y Home_score

Give variables meaningful names, which will help to make the program easier to read and follow. This simplifies the task of error correction.

ASSIGNING VALUES TO VARIABLES

Having declared a variable, you often want to make it equal to some value. In pascal, the special operator

:=

provides a means of assigning a value to a variable. The following portion of code, which appeared earlier, illustrates this.

var number1, number2, number3 : integer;

begin

number1 := 43; { make number1 equal to 43 decimal }

number2 := 34; { make number2 equal to 34 decimal }

number3 := number1 + number2; { number3 equals 77 }

When assigning values to char vari

1. Declare an integer called sum

sum : integer;

2. Declare a character called letter

letter : char;

3. Declare a variable called money which can be used to hold currency

money : real;

4. Declare an integer variable called total and initialise it to zero

total : integer;

total := 0;

5. Declare a variable called loop, which can hold any integer value

loop : integer;

![]() ARITHMETIC

STATEMENTS

ARITHMETIC

STATEMENTS

The following symbols represent the arithmetic operators, ie, use them when you wish to perform calculations.

+ Addition

- Subtraction

* Multiplication

/ Division

Addition Example

program Add (output);

var number1, number2, result : integer;

begin

number1 := 10;

number2 := 20;

result := number1 + number2;

writeln(number1, " plus ", number2, " is ", result )

end.

Subtraction Example

program Subtract (output);

var number1, number2, result : integer;

begin

number1 := 15;

number2 := 2;

result := number1 - number2;

writeln(number1, " minus ", number2, " is ", result )

end.

Multiplication Example

program Multiply (output);

var number1, number2, result : integer;

begin

number1 := 10;

number2 := 20;

result := number1 * number2;

writeln(number1, " multiplied by ", number2, " is ", result )

end.

Division Example

program Divide (output);

var number1, number2, result : integer;

begin

number1 := 20;

number2 := 10;

result := number1 / number2;

writeln(number1, " divided by ", number2, " is ", result )

end.

![]() DISPLAYING THE VALUE OR CONTENTS OF VARIABLES

DISPLAYING THE VALUE OR CONTENTS OF VARIABLES

The write or writeln statement displays the value of variables on the console screen. To print text, enclose inside single quotes. To display the value of a variable, do NOT enclose using single quotes, eg, the following program displays the content of each of the variables declared.

program DISPLAYVARIABLES (output);

var number1 : integer;

letter : char;

money : real;

begin

number1 := 23;

letter := 'W';

money := 23.73;

writeln('number1 = ', number1 );

writeln('letter = ', letter );

writeln('money = ', money )

end.

The display output from the above program will be,

number1 = 23

letter = W

money = 2.3730000000E+01

![]() GETTING

INFORMATION/DATA FROM THE KEYBOARD INTO A PROGRAM

GETTING

INFORMATION/DATA FROM THE KEYBOARD INTO A PROGRAM

It is convenient to accept data whilst a program is running. The read and readln statements allow you to read values and characters from the keyboard, placing them directly into specified variables.

The program which follows reads two numbers from the keyboard, assigns them to the specified variables, then prints them to the console screen.

program READDEMO (input, output);

var numb1, numb2 : integer;

begin

writeln('Please enter two numbers separated by a space');

read( numb1 );

read( numb2 );

writeln;

writeln('Numb1 is ', numb1 , ' Numb2 is ', numb2 )

end.

When run, the program will display the message

Please enter two numbers separated by a space

then wait for you to enter in the two numbers. If you typed the two numbers, then pressed the return key, eg,

237 64

then the program will accept the two numbers, assign the value 237 to numb1 and the value 64 to numb2, then continue and finally print

Numb1 is 237 Numb2 is 64

Differences between READ and READLN

The readln statement discards all other values on the same line, but read does not. In the previous program, replacing the read statements with readln and using the same input, the program would assign 237 to numb1, discard the value 64, and wait for the user to enter in another value which it would then assign to numb2.The is read as a blank by read, and ignored by readln.

![]() SPECIFYING THE DISPLAY FORMAT FOR THE OUTPUT OF VARIABLES

SPECIFYING THE DISPLAY FORMAT FOR THE OUTPUT OF VARIABLES

When variables are displayed, our version of Pascal assigns a specified number of character spaces (called a field width) to display them. The field widths for the various data types are,

INTEGER - Number of digits + 1 { or +2 if negative }

CHAR - 1 for each character

REAL - 12

BOOLEAN - 4 if true, 5 if false

Often, the allotted field size is too big for the majority of display output. Pascal provides a way in which the programmer can specify the field size for each output.

writeln('WOW':10,'MOM!':10,'Hi there.');

The display output will be as follows,

WOW.......MOM!......Hi there. ... indicates a space.

Note that to specify the field width of text or a particular variable, use a colon (:) followed by the field size.

'text string':fieldsize, variable:fieldsize

![]() INTEGER

DIVISION

INTEGER

DIVISION

There is a special operator, DIV, used when you wish to divide one integer by another (ie, you can't use / ). The following program demonstrates this,

program INTEGER_DIVISION (output);

var number1, number2, number3 : integer;

begin

number1 := 4;

number2 := 8;

number3 := number2 DIV number1;

writeln( number2:2,' divided by ',number1:2,' is ',number3:2)

end.

Sample Output

8 divided by 4 is 2

![]() MODULUS

MODULUS

The MOD keyword means MODULUS, ie, it returns the remainder when one number is divided by another,

The modulus of 20 DIV 5 is 0

The modulus of 21 DIV 5 is 1

program MODULUS (output);

var number1, number2, number3 : integer;

begin

number1 := 3;

number2 := 10;

number3 := number2 MOD number1;

writeln( number2:2,' modulus ',number1:2,' is ',number3:2)

end.

Sample Output

10 modulus 3 is 1

![]() MAKING

DECISIONS

MAKING

DECISIONS

Most programs need to make decisions. There are several statements available in the Pascal language for this. The IF statement is one of the them. The RELATIONAL OPERATORS, listed below, allow the programmer to test various variables against other variables or values.

= Equal to

> Greater than

< Less than

<> Not equal to

<= Less than or equal to

>= Greater than or equal to

The format for the IF THEN Pascal statement is,

if condition_is_true then

execute_this_program_statement;

The condition (ie, A < 5 ) is evaluated to see if it's true. When the condition is true, the program statement will be executed. If the condition is not true, then the program statement following the keyword then will be ignored.

program IF_DEMO (input, output); {Program demonstrating IF THEN statement}

var number, guess : integer;

begin

number := 2;

writeln('Guess a number between 1 and 10');

readln( guess );

if number = guess then writeln('You guessed correctly. Good on you!');

if number <> guess then writeln('Sorry, you guessed wrong.')

end.

Executing more than one statement as part of an IF

To execute more than one program statement when an if statement is true, the program statements are grouped using the begin and end keywords. Whether a semi-colon follows the end keyword depends upon what comes after it. When followed by another end or end. then it no semi-colon, eg,

program IF_GROUP1 (input, output);

var number, guess : integer;

begin

number := 2;

writeln('Guess a number between 1 and 10');

readln( guess );

if number = guess then

begin

writeln('Lucky you. It was the correct answer.');

writeln('You are just too smart.')

end;

if number <> guess then writeln('Sorry, you guessed wrong.')

end.

program IF_GROUP2 (input, output);

var number, guess : integer;

begin

number := 2;

writeln('Guess a number between 1 and 10');

readln( guess );

if number = guess then

begin

writeln('Lucky you. It was the correct answer.');

writeln('You are just too smart.')

end

end.

![]() IF THEN

ELSE

IF THEN

ELSE

The IF statement can also include an ELSE statement, which specifies the statement (or block or group of statements) to be executed when the condition associated with the IF statement is false. Rewriting the previous program using an IF THEN ELSE statement,

{ Program example demonstrating IF THEN ELSE statement }

program IF_ELSE_DEMO (input, output);

var number, guess : integer;

begin

number := 2;

writeln('Guess a number between 1 and 10');

readln( guess );

if number = guess then

writeln('You guessed correctly. Good on you!')

else

writeln('Sorry, you guessed wrong.')

end.

There are times when you want to execute more than one statement when a condition is true (or false for that matter). Pascal makes provison for this by allowing you to group blocks of code together by the use of the begin and end keywords. Consider the following portion of code,

if number = guess then

begin

writeln('You guessed correctly. Good on you!');

writeln('It may have been a lucky guess though')

end {no semi-colon if followed by an else }

else

begin

writeln('Sorry, you guessed wrong.');

writeln('Better luck next time')

end; {semi-colon depends on next keyword }

![]() THE AND

OR NOT STATEMENTS

THE AND

OR NOT STATEMENTS

The AND, OR and NOT keywords are used where you want to execute a block of code (or statement) when more than one condition is necessary.

AND The statement is executed only if BOTH conditions are true,

if (A = 1) AND (B = 2) then writeln('Bingo!');

OR The statement is executed if EITHER argument is true,

if (A = 1) OR (B = 2) then writeln('Hurray!');

NOT Converts TRUE to FALSE and vsvs

if NOT ((A = 1) AND (B = 2)) then writeln('Wow, really heavy man!');

![]() CONSTANTS

CONSTANTS

When writing programs, it is desirable to use values which do not change during the programs execution. An example would be the value of PI, 3.141592654

In a program required to calculate the circumference of several circles, it would be simpler to write the words PI, instead of its value 3.14. Pascal provides CONSTANTS to implement this.

To declare a constant, the keyword const is used, followed by the name of the constant, an equals sign, the constants value, and then a semi-colon, eg,

const PI = 3.141592654;

From now on, in the Pascal program, you use PI. When the program is compiled, the compiler replaces every occurrence of the word PI with its actual value. Thus, constants provide a short hand means of writing values, and help to make programs easier to read. The following program demonstrates the use of constants.

program CIRCUMFERENCE (input,output);

const PI = 3.141592654;

var Circumfer, Diameter : real;

begin

writeln('Enter the diameter of the circle');

readln(Diameter);

Circumfer := PI * Diameter;

writeln('The circles circumference is ',Circumfer)

end.

![]() SPECIFYING THE NUMBER OF DECIMAL PLACES FOR DISPLAYING REALS

SPECIFYING THE NUMBER OF DECIMAL PLACES FOR DISPLAYING REALS

The following change to the above program will print out the circumference using a fieldwidth of ten, and two decimal places.

writeln('The circles circumference is ',Circumference:10:2);

![]() LOOPS

LOOPS

The most common loop in Pascal is the FOR loop. The statement inside the for block is executed a number of times depending on the control condition. The format's for the FOR command is,

FOR var_name := initial_value TO final_value DO program_statement;

FOR var_name := initial_value TO final_value DO

begin

program_statement; {to execute more than one statement in a for }

program_statement; {loop, you group them using the begin and }

program_statement {end statements }

end; {semi-colon here depends upon next keyword }

FOR var_name := initial_value DOWNTO final_value DO program_statement;

You must not change the value of the control variable (var_name) inside the loop. The following program illustrates the for statement.

program CELCIUS_TABLE ( output );

var celcius : integer; farenhiet : real;

begin

writeln('Degree''s Celcius Degree''s Farenhiet');

for celcius := 1 to 20 do

begin

farenhiet := ( 9 / 5 ) * celcius + 32;

writeln( celcius:8, ' ',farenhiet:16:2 )

end

end.

![]() NESTED

LOOPS

NESTED

LOOPS

A for loop can occur within another, so that the inner loop (which contains a block of statements) is repeated by the outer loop.

RULES RELATED TO NESTED FOR LOOPS

1. Each loop must use a seperate variable

2. The inner loop must begin and end entirely within the outer loop.

![]() THE

WHILE LOOP

THE

WHILE LOOP

The while loop is similar to the for loop shown earlier, in that it allows a {group of} program statement(s) to be executed a number of times. The structure of the while statement is,

while condition_is_true do

begin

program statement;

program statement

end; {semi-colon depends upon next keyword}

or, if only a single program statement is to be executed,

while condition_is_true do program statement;

The program statement(s) are executed when the condition evaluates as true. Somewhere inside the loop the value of the variable which is controlling the loop (ie, being tested in the condition) must change so that the loop can finally exit.

![]() REPEAT

REPEAT

The REPEAT statement is similar to the while loop, how-ever, with the repeat statement, the conditional test occurs after the loop. The program statement(s) which constitute the loop body will be executed at least once. The format is,

repeat

program statement;

until condition_is_true; {semi-colon depends on next keyword}

There is no need to use the begin/end keywords to group more than one program statement, as all statements between repeat and until are treated as a block.

![]() The CASE

statement

The CASE

statement

The case statement allows you to rewrite code which uses a lot of if else statements, making the program logic much easier to read. Consider the following code portion written using if else statements,

if operator = '*' then result := number1 * number2

else if operator = '/' then result := number1 / number2

else if operator = '+' then result := number1 + number2

else if operator = '-' then result := number1 - number2

else invalid_operator = 1;

Rewriting this using case statements,

case operator of

'*' : result:= number1 * number2;

'/' : result:= number1 / number2;

'+' : result:= number1 + number2;

'-' : result:= number1 - number2;

otherwise invalid_operator := 1

end;

The value of operator is compared against each of the values specified. If a match occurs, then the program statement(s) associated with that match are executed. If operator does not match, it is compared against the next value. The purpose of the otherwise clause ensures that appropiate action is taken when operator does not match against any of the specified cases.

You must compare the variable against a constant, how-ever, it is possible to group cases as shown below,

case user_request of

'A' :

'a' : call_addition_subprogram;

's' :

'S' : call_subtraction_subprogram;

end;

![]() ENUMERATED DATA TYPES

ENUMERATED DATA TYPES

Enumerated variables are defined by the programmer. It allows you to create your own data types, which consist of a set of symbols. You first create the set of symbols, and assign to them a new data type variable name.

Having done this, the next step is to create working variables to be of the same type. The following portions of code describe how to create enumerated variables.

type civil_servant = ( clerk, police_officer, teacher, mayor );

var job, office : civil_servant;

The new data type created is civil_servant. It is a set of values, enclosed by the ( ) parenthesis. These set of values are the only ones which variables of type civil_servant can assume or be assigned. The next line declares two working variables, job and office, to be of the new data type civil_servant.

The following assignments are valid,

job := mayor;

office := teacher;

if office = mayor then writeln('Hello mayor!');

The list of values or symbols between the parenthesis is an ordered set of values. The first symbol in the set has an ordinal value of zero, and each successive symbol has a value of one greater than its predecessor.

police_officer < teacher

evaluates as true, because police_officer occurs before teacher in the set.

MORE EXAMPLES ON ENUMERATED DATA TYPES

type beverage = ( coffee, tea, cola, soda, milk, water );

color = ( green, red, yellow, blue, black, white );

var drink : beverage;

chair : color;

drink := coffee;

chair := green;

if chair = yellow then drink := tea;

![]() ADDITIONAL OPERATIONS WITH USER DEFINED VARIABLE TYPES

ADDITIONAL OPERATIONS WITH USER DEFINED VARIABLE TYPES

Consider the following code,

type Weekday = ( Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday );

var Workday : Weekday;

The first symbol of the set has the value of 0, and each symbol which follows is one greater. Pascal provides three additional operations which are performed on user defined variables. The three operations are,

ord( symbol ) returns the value of the symbol, thus ord(Tuesday)

will give a value of 1

pred( symbol ) obtains the previous symbol, thus

pred(Wednesday) will give Tuesday

succ( symbol ) obtains the next symbol, thus succ(Monday)

gives Tuesday

Enumerated values can be used to set the limits of a for statement, or as a constant in a case statement, eg,

for Workday := Monday to Friday

.........

case Workday of

Monday : writeln('Mondays always get me down.');

Friday : writeln('Get ready for partytime!')

end;

Enumerated type values cannot be input from the keyboard or outputted to the screen, so the following statements are illegal,

writeln( drink );

readln( chair );

![]() SUBRANGES

SUBRANGES

Just as you can create your own set of pre-defined data types, you can also create a smaller subset or subrange of an existing set which has been previously defined. Each subrange consists of a defined lower and upper limit. Consider the following,

type DAY = (Monday,Tuesday,Wednesday,Thursday,Friday,Saturday,Sunday);

Weekday = Monday..Friday; {subrange of DAY}

Weekend = Saturday..Sunday; {subrange of DAY}

Hours = 0..24; {subrange of integers}

Capitals= 'A'..'Z'; {subrange of characters}

NOTE: You cannot have subranges of type real.

![]() ARRAYS

ARRAYS

An array is a structure which holds many variables, all of the same data type. The array consists of so many elements, each element of the array capable of storing one piece of data (ie, a variable).

An array is defined as follows,

type array_name = ARRAY [lower..upper] of data_type;

Lower and Upper define the boundaries for the array. Data_type is the type of variable which the array will store, eg, type int, char etc. A typical declaration follows,

type intarray = ARRAY [1..20] of integer;

This creates a definition for an array of integers called intarray, which has 20 separate locations numbered from 1 to 20. Each of these positions (called an element), holds a single integer. The next step is to create a working variable to be of the same type, eg,

var numbers : intarray;

Each element of the numbers array is individually accessed and updated as desired. To assign a value to an element of an array, use

numbers[2] := 10;

This assigns the integer value 10 to element 2 of the numbers array. The value or element number (actually its called an index) is placed inside the square brackets. To assign the value stored in an element of an array to a variable, use

number1 := numbers[2];

This takes the integer stored in element 2 of the array numbers, and makes the integer number1 equal to it. Consider the following array declarations

const size = 10;

last = 100;

type sub = 'a'..'z';

color = (green, yellow, red, orange, blue );

var chararray : ARRAY [1..size] of char; {an array of 10 characters. First element is chararray[1], last element is chararry[10] }

intarray : ARRAY [sub] of integer; {an array of 26 integers. First element is intarray['a'] last element is intarray['z'] }

realarray : ARRAY [5..last] of real; {an array of 95 real numbers. First element is realarray[5] last element is realarray[100] }

artstick : ARRAY [-3..2] of color; {an array of 6 colors. First element is artstick[-3] last element is artstick[2] }

huearray : ARRAY [color] of char; {an array of 6 characters. First element is huearray[green] last element is huearray[blue] }

![]() CHARACTER ARRAYS

CHARACTER ARRAYS

You can have arrays of characters. Text strings from the keyboard may be placed directly into the array elements. You can print out the entire character array contents. The following program illustrates how to do this,

program CHARRAY (input,output );

type word = PACKED ARRAY [1..10] of char;

var word1 : word;

loop : integer;

begin

writeln('Please enter in up to ten characters.');

readln( word1 ); { this reads ten characters directly from the

standard input device, placing each character

read into subsequent elements of word1 array }

writeln('The contents of word1 array is ');

for loop := 1 to 10 do {print out each element}

writeln('word1[',loop,'] is ',word1[loop] );

writeln('Word1 array contains ', word1 ) {print out entire array}

end.

Note the declaration of PACKED ARRAY, and the use of just the array name in conjuction with the readln statement. If the user typed in

Hello there

then the contents of the array word1 will be,

word1[1] = H

word1[2] = e

word1[3] = l

word1[4] = l

word1[5] = o

word1[6] = { a space }

word1[7] = t

word1[8] = h

word1[9] = e

word1[10]= r

The entire contents of a packed array of type char can also be outputted to the screen simply the using the array name without an index value, ie, the statement

writeln('Word1 array contains ', word1 );

will print out all elements of the array word1, displaying

Hello ther

![]() INTEGER

ARRAYS

INTEGER

ARRAYS

Arrays can hold any of the valid data types, including integers. Integer arrays cannot be read or written as an entire unit, only packed character arrays can. The following program demonstrates an integer array, where ten successive numbers are inputted, stored in separate elements of the array numbers, then finally outputted to the screen one at a time.

program INT_ARRAY (input,output );

type int_array = ARRAY [1..10] of integer;

var numbers : int_array;

loop : integer;

begin

writeln('Please enter in up to ten integers.');

for loop := 1 to 10 do

readln( numbers[loop] );

writeln('The contents of numbers array is ');

{ print out each element }

for loop := 1 to 10 do

writeln('numbers[',loop:2,'] is ',numbers[loop] )

end.

INITIALISATION OF PACKED CHARACTER ARRAYS

Packed arrays of characters are initialised by equating the array to a text string enclosed by single quotes, eg,

type string = PACKED ARRAY [1..15] of char;

var message : string;

message := 'Good morning! '; {must be fifteen characters long}

MULTIDIMENSIONED ARRAYS

The following statement creates a type definition for an integer array called multi of 10 by 10 elements (100 in all). Remember that arrays are split up into row and columns. The first index is the row, the second index is the column.

type multi = ARRAY [1..10, 1..10] of integer;

begin work : multi;

To print out each of the various elements of work, consider

for row := 1 to 10 do

for column := 1 to 10 do

writeln('Multi[',row,',',column,'] is ',multi[row,column];

HOW CHARACTERS ARE INTERNALLY REPRESENTED

Internally, most computers store characters according to the ASCII format. ASCII stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange. Characters are stored according to a numbered sequence, whereby A has a value of 64 decimal, B a value of 65 etc. Several functions which manipulate characters follow.

CHR

The chr or character position function returns the character associated with the ASCII value being asked, eg,

chr( 65 ) will return the character A

ORD

The ord or ordinal function returns the ASCII value of a requested character. In essence, it works backwards to the chr function. Ordinal data types are those which have a predefined, known set of values.

Each value which follows in the set is one greater than the previous. Characters and integers are thus ordinal data types.

ord( 'C' ) will return the value 67

SUCC

The successor function determines the next value or symbol in the set, thus

succ( 'd' ) will return e

PRED

The predecessor function determines the previous value or symbol in the set, thus

pred( 'd' ) will return c

COMPARISON OF CHARACTER VARIABLES

Character variables, when compared against each other, is done using the ASCII value of the character. Consider the following portion of code,

var letter1, letter2 : char;

begin

letter1 := 'A'; letter2 := 'C';

if letter1 < letter2 then

writeln( letter1, ' is less than ',letter2 )

else

writeln( letter2, ' is less than ',letter1 )

end.

STRING ARRAYS, COMPARISON OF

Packed character arrays of the same length are comparable. There follows a short program illustrating this,

program PACKED_CHAR_COMPARISON (output);

type string1 = packed array [1..6] of char;

var letter1, letter2 : string1;

begin

letter1 := 'Hello ';

letter2 := 'HellO ';

if letter1 < letter2 then

writeln( letter1,' is less than ',letter2)

else

writeln( letter2,' is less than ',letter1)

end.

![]() COMMON

FUNCTIONS

COMMON

FUNCTIONS

The Pascal language provides a range of functions to perform data transformation and calculations. The following section provides an explanation of the commonly provided functions,

ABS

The ABSolute function returns the absolute value of either an integer or real, eg,

ABS( -21 ) returns 21

ABS( -3.5) returns 3.5000000000E+00

COS

The COSine function returns the cosine value, in radians, of an argument, eg,

COS( 0 ) returns 1.0

EXP

The exponential function calculates e raised to the power of a number, eg,

EXP(10 ) returns e to the power of 10

There is no function in Pascal to calculate expressions such as an, ie,

23 is 2*2*2 = 8

These are calculated by using the formula

an = exp( n * ln( a ) )

LN

The logarithm function calculates the natural log of a number greater than zero.

ODD

The odd function determines when a specified number is odd or even, returning true when the number is odd, false when it is not.

ROUND

The round function rounds its number (argument) to the nearest integer. If the argument is positive

rounding is up for fractions greater than or equal to .5

rounding is down for fractions less than .5

If the number is negative

rounding is down (away from zero) for fractions >= .5

rounding is up (towards zero) for fractions < .5

SIN

The sine function returns the sine of its argument, eg,

SIN( PI / 2 ) returns 1.0

SQR

The square function returns the square (ie the argument multiplied by itself) of its supplied argument,

SQR( 2 ) returns 4

SQRT

This function returns {always returns a real} the square root of its argument, eg,

SQRT( 4 ) returns 2.0000000000E+00

TRUNC

This function returns the whole part (no decimal places) of a real number.

TRUNC(4.87) returns 4

TRUNC(-3.4) returns 3

![]() MODULAR

PROGRAMMING USING PROCEDURES AND FUNCTIONS

MODULAR

PROGRAMMING USING PROCEDURES AND FUNCTIONS

Modular programming is a technique used for writing large programs. The program is subdivided into small sections. Each section is called a module, and performs a single task.

Examples of tasks a module might perform are,

displaying an option menu

printing results

calculating average marks

sorting data into groups

A module is known by its name, and consists of a set of program statements grouped using the begin and end keywords. The module (group of statements) is executed when you type the module name. Pascal uses three types of modules. The first two are called PROCEDURES, the other a FUNCTION.

Simple procedures do not accept any arguments (values or data) when the procedure is executed (called).

Complex procedures accept values to work with when they are executed.

Functions, when executed, return a value (ie, calculate an answer which is made available to the module which wants the answer)

Procedures help support structured program design, by allowing the independant development of modules. Procedures are essentially sub-programs.

SIMPLE PROCEDURES

Procedures are used to perform tasks such as displaying menu choices to a user. The procedure (module) consists of a set of program statements, grouped by the begin and end keywords. Each procedure is given a name, similar to the title that is given to the main module.

Any variables used by the procedure are declared before the keyword begin.

PROCEDURE DISPLAY_MENU;

begin

writeln('<14>Menu choices are');

writeln(' 1: Edit text file');

writeln(' 2: Load text file');

writeln(' 3: Save text file');

writeln(' 4: Copy text file');

writeln(' 5: Print text file')

end;

The above procedure called DISPLAY_MENU, simply executes each of the statements in turn. To use this in a program, we write the name of the procedure, eg,

program PROC1 (output);

PROCEDURE DISPLAY_MENU;

begin

writeln('<14>Menu choices are');

writeln(' 1: Edit text file');

writeln(' 2: Load text file');

writeln(' 3: Save text file');

writeln(' 4: Copy text file');

writeln(' 5: Print text file')

end;

begin

writeln('About to call the procedure');

DISPLAY_MENU;

writeln('Now back from the procedure')

end.

In the main portion of the program, it executes the statement

writeln('About to call the procedure');

then calls the procedure DISPLAY_MENU. All the statements in this procedure are executed, at which point we go back to the statement which follows the call to the procedure in the main section, which is,

writeln('Now back from the procedure')

The sample output of the program is

About to call the procedure

Menu choices are

1: Edit text file

2: Load text file

3: Save text file

4: Copy text file

5: Print text file

Now back from the procedure

PROCEDURES AND LOCAL VARIABLES

A procedure can declare it's own variables to work with. These variables belong to the procedure in which they are declared. Variables declared inside a procedure are known as local.

Local variables can be accessed anywhere between the begin and matching end keywords of the procedure. The following program illustrates the use and scope (where variables are visible or known) of local variables.

program LOCAL_VARIABLES (input, output);

var number1, number2 : integer; {these are accessible by all}

procedure add_numbers;

var result : integer; {result belongs to add_numbers}

begin

result := number1 + number2;

writeln('Answer is ',result)

end;

begin {program starts here}

writeln('Please enter two numbers to add together');

readln( number1, number2 );

add_numbers

end.

PROCEDURES WHICH ACCEPT ARGUMENTS

Procedures may also accept variables (data) to work with when they are called.

Declaring the variables within the procedure

The variables accepted by the procedure are enclosed using parenthesis.

The declaration of the accepted variables occurs between the procedure name and the terminating semi-colon.

Calling the procedure and Passing variables (or values) to it

When the procedure is invoked, the procedure name is followed by a set of parenthesis.

The variables to be passed are written inside the parenthesis.

The variables are written in the same order as specified in the procedure.

Consider the following program example,

program ADD_NUMBERS (input, output);

procedure CALC_ANSWER ( first, second : integer );

var result : integer;

begin

result := first + second;

writeln('Answer is ', result )

end;

var number1, number2 : integer;

begin

writeln('Please enter two numbers to add together');

readln( number1, number2 );

CALC_ANSWER( number1, number2)

end.

![]() Value

Parameters

Value

Parameters

In the previous programs, when variables are passed to procedures, the procedures work with a copy of the original variable. The value of the original variables which are passed to the procedure are not changed.

The copy that the procedure makes can be altered by the procedure, but this does not alter the value of the original. When procedures work with copies of variables, they are known as value parameters.

Consider the following code example,

program Value_Parameters (output);

procedure Nochange ( letter : char; number : integer );

begin

writeln( letter );

writeln( number );

letter := 'A'; {this does not alter mainletter}

number := 32; {this does not alter mainnumber}

writeln( letter );

writeln( number )

end;

var mainletter : char; {these variables known only from here on}

mainnumber : integer;

begin

mainletter := 'B';

mainnumber := 12;

writeln( mainletter );

writeln( mainnumber );

Nochange( mainletter, mainnumber );

writeln( mainletter );

writeln( mainnumber )

end.

Variable parameters

Procedures can also be implemented to change the value of original variables which are accepted by the procedure. To illustrate this, we will develop a little procedure called swap. This procedure accepts two integer values, swapping them over.

Previous procedures which accept value parameters cannot do this, as they only work with a copy of the original values. To force the procedure to use variable parameters, preceed the declaration of the variables (inside the parenthesis after the function name) with the keyword var.

This has the effect of using the original variables, rather than a copy of them.

program Variable_Parameters (output);

procedure SWAP ( var value1, value2 : integer );

var temp : integer;

begin

temp := value1;

value1 := value2; {value1 is actually number1}

value2 := temp {value2 is actually number2}

end;

var number1, number2 : integer;

begin

number1 := 10;

number2 := 33;

writeln( 'Number1 = ', number1,' Number2 = ', number2 );

SWAP( number1, number2 );

writeln( 'Number1 = ', number1,' Number2 = ', number2 )

end.

When this program is run, it prints out

Number1 = 10 Number2 = 33

Number1 = 33 Number2 = 10

![]() FUNCTIONS - A SPECIAL TYPE OF PROCEDURE WHICH RETURNS A VALUE

FUNCTIONS - A SPECIAL TYPE OF PROCEDURE WHICH RETURNS A VALUE

Procedures accept data or variables when they are executed. Functions also accept data, but have the ability to return a value to the procedure or program which requests it. Functions are used to perform mathematical tasks like factorial calculations.

A function

begins with the keyword function

is similar in structure to a procedure

somewhere inside the code associated with the function, a value is assigned to the function name

a function is used on the righthand side of an expression

can only return a simple data type

The actual heading of a function differs slightly than that of a procedure. Its format is,

function Function_name (variable declarations) : return_data_type;

After the parenthesis which declare those variables accepted by the function, the return data type (preceeded by a colon) is declared.

function ADD_TWO ( value1, value2 : integer ) : integer;

begin

ADD_TWO := value1 + value2

end;

The following line demonstrates how to call the function,

result := ADD_TWO( 10, 20 );

thus, when ADD_TWO is executed, it equates to the value assigned to its name (in this case 30), which is then assigned to result.

![]() RECORDS

RECORDS

A record is a user defined data type suitable for grouping data elements together. All elements of an array must contain the same data type.

A record overcomes this by allowing us to combine different data types together. Suppose we want to create a data record which holds a student name and mark. The student name is a packed array of characters, and the mark is an integer.

We could use two seperate arrays for this, but a record is easier. The method to do this is,

define or declare what the new data group (record) looks like

create a working variable to be of that type

The following portion of code shows how to define a record, then create a working variable to be of the same type.

TYPE studentname = packed array[1..20] of char;

studentinfo = RECORD

name : studentname;

mark : integer

END;

VAR student1 : studentinfo;

The first portion defines the composition of the record identified as studentinfo. It consists of two parts (called fields). The first part of the record is a packed character array identified as name. The second part of studentinfo consists of an integer, identified as mark.

The declaration of a record begins with the keyword record, and ends with the keyword end;

The next line declares a working variable called student1 to be of the same type (ie composition) as studentinfo.

Each of the individual fields of a record are accessed by using the format,

recordname.fieldname := value or variable;

An example follows,

student1.name := 'JOE BLOGGS '; {20 characters}

student1.mark := 57;

Lets create a new data record suitable for storing the date

type date = RECORD

day : integer;

month : integer;

year : integer

END;

This declares a NEW data type called date. This date record consists of three basic data elements, all integers. Now declare working variables to use in the program. These variables will have the same composition as the date record.

var todays_date : date;

defines a variable called todays_date to be of the same data type as that of the newly defined record date.

ASSIGNING VALUES TO RECORD ELEMENTS

These statements assign values to the individual elements of the record todays_date,

todays_date.day := 21;

todays_date.month := 07;

todays_date.year := 1985;

NOTE the use of the .fieldname to reference the individual fields within todays_date.

Sample program illustrating records

program RECORD_INTRO (output);

type date = record

month, day, year : integer

end;

var today : date;

begin

today.day := 25;

today.month := 09;

today.year := 1983;

writeln('Todays date is ',today.day,':',today.month,':',

today.year)

end.

Records of the same type are assignable.

var todays_date, tomorrows_date : date;

begin

todays_date.day := 9;

todays_date.month := 7;

todays_date.year := 1976;

tomorrows_date := todays_date;

The last statement copies all the elements of todays_date into the elements of tomorrows_date. This statement adds one to the value stored in the field day of the record tomorrows_date.

tomorrows_date.day := tomorrows_date.day + 1;

RECORDS AND PROCEDURES

The following program demonstrates passing a record to a procedure, which updates the record, then prints the updated time.

program TIME (input,output);

type time = record

seconds, minutes, hours : integer

end;

var current, next : time;

{ function to update time by one second }

procedure timeupdate( var now : time); {variable parameter}

var newtime : time; {local variable}

begin

newtime := now; {use local instead of orginal}

newtime.seconds := newtime.seconds + 1;

if newtime.seconds = 60 then

begin

newtime.seconds := 0;

newtime.minutes := newtime.minutes + 1;

if newtime.minutes = 60 then

begin

newtime.minutes := 0;

newtime.hours := newtime.hours + 1;

if newtime.hours = 24 then

newtime.hours := 0

end

end;

writeln('The updated time is ',newtime.hours,':',newtime.minutes,

':',newtime.seconds)

end;

begin

writeln('Please enter in the time using hh mm ss');

readln( current.hours, current.minutes, current.seconds );

timeupdate( current )

end.

ARRAYS OF RECORDS

can also be created, in the same way as arrays of any of the four basic data types. The following statement declares a record called date.

type date = record

month, day, year : integer

end;

Lets now create an array of these records, called birthdays.

var birthdays : array[1..10] of date;

This creates an array of 10 elements. Each element consists of a record of type date, ie, each element consists of three integers, called month, day and year. Pictorially it looks like,

|----------------|

| month | <----<----------------

|----------------| | |

| day | |--Element 1 |

|----------------| | |

| year | <---- |

|----------------| |

| month | <---- |

|----------------| | |

| day | |--Element 2 |

|----------------| | |--< birthdays

| year | <---- |

|----------------| |

|

|----------------| |

| month | <---- |

|----------------| | |

| day | |--Element 10 |

|----------------| | |

| year | <----<----------------

|----------------|

Consider the following assignment statements.

birthdays[1].month := 2;

birthdays[1].day := 12;

birthdays[1].year := 1983;

birthdays[1].year := birthdays[2].year;

which assign various values to the array elements.

RECORDS CONTAINING ARRAYS

Records can also contain arrays as a field. Consider the following example, which shows a record called month, whose element name is actually an array.

type monthname = packed array[1..4] of char;

month = RECORD

days : integer;

name : monthname

END;

var this_month : month;

this_month.days := 31; this_month.name[0] := 'J';

this_month.name[1] := 'a'; this_month.name[2] := 'n';

this_month.name := 'Feb ';

RECORDS WITHIN RECORDS

Records can also contain other records as a field. Consider where both a date and time record are combined into a single record called date_time, eg,

type date = RECORD

day, month, year : integer

END;

time = RECORD

hours, minutes, seconds : integer

END;

date_time = RECORD

sdate : date;

stime : time

END;

This defines a record whose elements consist of two other previously declared records. The statement

var today : date_time;

declares a working variable called today, which has the same composition as the record date_time. The statements

today.sdate.day := 11;

today.sdate.month := 2;

today.sdate.year := 1985;

today.stime.hours := 3;

today.stime.minutes := 3;

today.stime.seconds := 33;

sets the sdate element of the record today to the eleventh of february, 1985. The stime element of the record is initialised to three hours, three minutes, thirty-three seconds

with RECORDS

The with statement, in association with records, allows a quick and easy way of accessing each of the records members without using the dot notation.

Consider the following program example, where the variable student record is initialised. Note how the name of the record is associated with each of the initialised parts. Then look at the code that follows, and note the difference being the absence of the record name.

program withRecords( output );

typeGender = (Male, Female);

Person = Record

Age : Integer;

Sex : Gender

end;

var Student : Person;

begin

Student.Age := 23;

Student.Sex := Male;

with Student do begin

Age := 19;

Sex := Female

end;

with Student do begin

Writeln( 'Age := ', Age );

case Sex of

Male : Writeln( 'Sex := Male' );

Female : Writeln( 'Sex := Female' )

end

end

end.

![]() SETS

SETS

Sets exist in every day life. They are a way of classifying common types into groups. In Pascal, we think of sets as containing a range of limited values, from an initial value through to an ending value.

Consider the following set of integer values,

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

This is a set of numbers (integers) whose set value ranges from 1 to 10. To define this as a set type in Pascal, we would use the following syntax.

program SetsOne( output );

type numberset = set of 1..10;

var mynumbers : numberset;

begin

end.

The statement

type numberset = set of 1..10;

declares a new type called numberset, which represents a set of integer values ranging from 1 as the lowest value, to 10 as the highest value. The value 1..10 means the numbers 1 to 10 inclusive. We call this the base set, that is, the set of values from which the set is taken. The base set is a range of limited values. For example, we can have a set of char, but not a set of integers, because the set of integers has too many possible values, whereas the set of characters is very limited in possible values.

The statement

var mynumbers : numberset;

makes a working variable in our program called mynumbers, which is a set and can hold any value from the range defined in numberset.

SET OPERATIONS

The typical operations associated with sets are,

assign values to a set

determine if a value is in one or more sets

set addition (UNION)

set subtraction (DIFFERENCE)

set commonality (INTERSECTION)

Assigning Values to a set: UNION

Set union is essentially the addition of sets, which also includes the initialisation or assigning of values to a set. Consider the following statement which assigns values to a set

program SetsTWO( output );

type numberset = set of 1..10;

var mynumbers : numberset;

begin

mynumbers := [];

mynumbers := [2..6]

end.

The statement

mynumbers := [];

assigns an empty set to mynumbers. The statement

mynumbers := [2..6];

assigns a subset of values (integer 2 to 6 inclusive) from the range given for the set type numberset. Please note that assigning values outside the range of the set type from which mynumbers is derived will generate an error, thus the statement

mynumbers := [6..32];

is illegal, because mynumbers is derived from the base type numberset, which is a set of integer values ranging from 1 to 10. Any values outside this range are considered illegal. Determining if a value is in a set

Lets expand the above program example to demonstrate how we check to see if a value resides in a set. Consider the following program, which reads an integer from the keyboard and checks to see if its in the set.

program SetsTHREE( input, output );

type numberset = set of 1..10;

var mynumbers : numberset;

value : integer;

begin

mynumbers := [2..6];

value := 1;

while( value <> 0 ) do

begin

writeln('Please enter an integer value, (0 to exit)');

readln( value );

if value <> 0 then

begin

if value IN mynumbers then

writeln('Its in the set')

else

writeln('Its not in the set')

end

end

end.

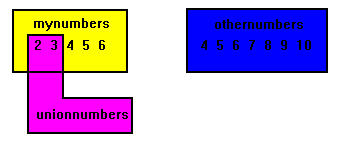

More on set UNION, combining sets

Lets now look at combining some sets together. Consider the following program, which creates two sets, then joins the sets together to create another.

program SetsUNION( input, output );

type numberset = set of 1..40;

var mynumbers, othernumbers, unionnumbers : numberset;

value : integer;

begin

mynumbers := [2..6];

othernumbers := [4..10];

unionnumbers := mynumbers + othernumbers + [14..20];

value := 1;

while( value <> 0 ) do

begin

writeln('Please enter an integer value, (0 to exit)');

readln( value );

if value <> 0 then

begin

if value IN unionnumbers then

writeln('Its in the set')

else

writeln('Its not in the set')

end

end

end.

The statement

var mynumbers, othernumbers, unionnumbers : numberset;

declares three sets of type numberset. The statement

mynumbers := [2..6];

assigns a subset of values (integer 2 to 6 inclusive) from the range given for the set type numberset. The statement

othernumbers := [4..10];

assigns a subset of values (integer 4 to 10 inclusive) from the range given for the set type numberset. The statement

unionnumbers := mynumbers + othernumbers + [14..20];

assigns the set of values in mynumbers, othernumbers and the set of values of 14 to 20 to unionnumbers. If a specific value occurs in more than one set (as is the case of 4, 5, and 6, which are in mynumbers and othernumbers), then the other duplicate value is ignored (ie, only one instance of the value is copied to the new set.

This means that unionnumbers contains the values

Set Subtraction, DIFFERENCE

In this operation, the new set will contain the values of the first set that are NOT also in the second set.

program SetsDIFFERENCE( input, output );

type numberset = set of 1..40;

var mynumbers, othernumbers, unionnumbers : numberset;

value : integer;

begin

mynumbers := [2..6];

othernumbers := [4..10];

unionnumbers := mynumbers - othernumbers;

value := 1;

while( value <> 0 ) do

begin

writeln('Please enter an integer value, (0 to exit)');

readln( value );

if value <> 0 then

begin

if value IN unionnumbers then

writeln('Its in the set')

else

writeln('Its not in the set')

end

end

end.

unionnumbers contains the values

Set Commonality, INTERSECTION

In this operation, the new set will contain the values which are common (appear as members) of the specified sets.

program SetsINTERSECTION( input, output );

type numberset = set of 1..40;

var mynumbers, othernumbers, unionnumbers : numberset;

value : integer;

begin

mynumbers := [2..6];

othernumbers := [4..10];

unionnumbers := mynumbers * othernumbers * [5..7];

value := 1;

while( value <> 0 ) do

begin

writeln('Please enter an integer value, (0 to exit)');

readln( value );

if value <> 0 then

begin

if value IN unionnumbers then

writeln('Its in the set')

else

writeln('Its not in the set')

end

end

end.

unionnumbers contains the values

FILE HANDLING

So far, data has been inputted from the keyboard, and outputted to the console screen.

The keyboard is known as the standard input device, and the console screen is the standard output device. Pascal names these as INPUT and OUTPUT respectively.

Occasions arise where data must be derived from another source other than the keyboard. This data will exist external to the program, either stored on diskette, or derived from some hardware device.

In a lot of cases, hardcopy (a printout) of program results is needed, thus the program will send the output to either the printer or the disk instead of the screen.

A program which either reads information from, or writes information to, a place on a disk, is performing FILE Input/Output (I/O).

A File is a collection of information. In Pascal, this information may be arranged as text (ie a sequence of characters), as numbers (a sequence of integers or reals), or as records. The information is collectively known by a sequence of characters, called a FILENAME.

You have already used filenames to identify the source programs written and used in this tutorial.

USING A FILE IN PASCAL

Files are referred to in Pascal programs by the use of filenames. You have already used two default filenames, input and output. These are associated with the keyboard and console screen. To derive data from another source, it must be specified in the program heading, eg,

program FILE_OUTPUT( input, fdata );

This informs Pascal that you will be using a file called fdata. Within the variable declaration section, the file type is declared, eg

var fdata : file of char;

This declares the file fdata as consisting of a sequence of characters. Pascal provides a standard definition called TEXT for this, so the following statement is identical,

var fdata : TEXT;

BASIC FILE OPERATIONS

Once the file is known to the program, the operations which may be performed are, The file is prepared for use by RESET or REWRITE

Information is read or written using READ or WRITE

The file is then closed by using CLOSE

PREPARING A FILE READY FOR USE

The two commands for preparing a file ready for use in a program are RESET and REWRITE. Both procedures use the name of the file variable you want to work with. They also accept a string which is then associated with the file variable, eg

var filename : string[15];

readln( filename );

RESET ( fdata, filename );

This prepares the file specified by filename for reading. All reading operations are performed using fdata.

REWRITE ( fdata, filename );

This prepares the file specified by filename for writing. All write operations are performed using fdata. If the file already exists, it is re-created, and all existing information lost!

READING AND WRITING TO A FILE OF TYPE TEXT

The procedures READ and WRITE can be used. These procedures also accept the name of the file, eg,

writeln( fdata, 'Hello there. How are you?');

writes the text string to the file fdata rather than the standard output device. Turbo Pascal users must use the assign statement, as only one parameter may be supplied to either reset or rewrite.

assign( fdata, filename );

reset( fdata );

rewrite( fdata );

CLOSING A FILE

When all operations are finished, the file is closed. This is necessary, as it informs the program that you have finished with the file. The program releases any memory associated with the file, ensuring its (the files) integrity.

CLOSE( fdata ); {closes file associated with fdata}

Once a file has been closed, no further file operations on that file are possible (unless you prepare it again).

SAMPLE FILE OUTPUT PROGRAM TO WRITE DATA TO A TEXT FILE

program WRITETEXT (input, output, fdata );

var fdata : TEXT;

ch : char;

fname : packed array [1..15] of char;

begin

writeln('Enter a filename for storage of text.');

readln( fname );

rewrite( fdata, fname ); {create a new fdata }

readln; {clear input buffer }

read( ch ); {read character from keyboard}

while ch <> '*' do {stop when an * is typed }

begin

write( fdata, ch ); {write character to fdata }

read( ch ) {read next character }

end;

write( fdata, '*'); {write an * for end of file }

close( fdata ) {close file fdata }

end.

THE COMPOSITION OF TEXT FILES

Text files are arranged as a sequence of variable length lines.

Each line consists of a sequence of characters.

Each line is terminated with a special character, called

END-OF-LINE (EOLN)

The last character is another special character, called

END-OF-FILE (EOF)

THIS IS WHAT A TEXT FILE LOOKS LIKE

He was not quite as old as people estimated. In fact, the furrowedEOLN

brow that swept many a street was only fourty-five.EOLN

Life had not been easy for the hunchback, it's difficult to playEOLN

any game when all you can see are your feet. In spite of theEOLN

hardships, he was as gentle as a roaring elephant going overEOLN

Niagara falls.EOF

End of File and End of Line

EOF

Accepts the name of the input file, and returns true if there is no more data to be read.

EOLN

Accepts the name of the input file, and is true if there are no more characters on the current line.

When reading information from a text file, the character which is read can be compared against EOLN or EOF. Consider the following program which displays the contents of a text file on the console screen.

program SHOWTEXT ( infile, input, output );

var ch : char;

fname : packed array [1..15] of char;

infile: TEXT;

begin

writeln('Please enter name of text file to display.');

readln( fname );

reset( infile, fname ); {open a file using filename stored in}

{array fname }

while not eof( infile ) do

begin

while not eoln( infile ) do

begin

read( infile, ch );

write( ch )

end;

readln( infile ); {read eoln character}

writeln {write eoln character}

end;

close( infile ) {close filename specified by fname}

end.

FILES OF NUMBERS

Files may also consist of integers or reals. The procedures read and write can be used to transfer one value at a time.

The procedures readln and writeln cannot be used with file types other than text.

FILES OF RECORDS

Files can also contain records. Using read or write, it is possible to transfer a record at a time.

STRINGS

The following program illustrates using STRINGS (a sequence of characters) in a DG Pascal program. STRING is type defined as a packed array of type char.

Message is then declared as the same type as STRING, ie, a packed array of characters, elements numbered one to eight.

PROGRAM DGSTRING (INPUT, OUTPUT);

TYPE STRING = PACKED ARRAY [1..8] OF CHAR;

VAR MESSAGE : STRING;

BEGIN

WRITELN('HELLO BRIAN.');

MESSAGE := '12345678';

WRITELN('THE MESSAGE IS ', MESSAGE)

END.

Turbo Pascal, how-ever, allows an easier use of character strings by providing a new keyword called STRING. Using STRING, you can add a parameter (how many characters) specifying the string length. Consider the above program re-written for turbo pascal.

PROGRAM TPSTRING (INPUT, OUTPUT);

VAR MESSAGE : STRING[8];

BEGIN

WRITELN('HELLO BRIAN.');

MESSAGE := '12345678';

WRITELN('THE MESSAGE IS ', MESSAGE)

END.

Obviously, the turbo pascal version is easier to use. BUT, the following program shows a similar implementation for use on the DG.

PROGRAM DGSTRING2 (INPUT, OUTPUT);

CONST $STRINGMAXLENGTH = 8; {defines maxlength of a string}

%INCLUDE 'PASSTRINGS.IN'; {include code to handle strings}

VAR MESSAGE : $STRING_BODY;

BEGIN

WRITELN('HELLO BRIAN.');

MESSAGE := '12345678';

WRITELN('THE MESSAGE IS ', MESSAGE)

END.

Strings

DG Pascal also provides the following functions for handling and manipulating strings.

APPEND

concatenate two strings. calling format is

APPEND( string1, string2 );

where string2 is added onto the end of string1.

LENGTH

returns a short_integer which represents the length (number of

characters) of the string.

LENGTH( stringname );

SETSUBSTR

replaces a substring in a target string with a substring from

a source string.

SETSUBSTR( Targetstr, tstart, tlen, Sourcestr, sstart );

where

Targetstr is the target string

tstart is an integer representing the start position

(within Targetstr) of the substring that is to be replaced

tlen is an integer representing the length of the substring

that you are replacing in Targetstr

Sourcestr is the source string which contains the substring

sstart is an integer which specifies the starting position

of the substring within Sourcestr

![]() POINTERS

POINTERS

Pointers enable us to effectively represent complex data structures, to change values as arguments to functions, to work with memory which has been dynamically allocated, and to store data in complex ways.

A pointer provides an indirect means of accessing the value of a particular data item. Lets see how pointers actually work with a simple example,

program pointers1( output );

typeint_pointer = ^integer;

variptr : int_pointer;

begin

new( iptr );

iptr^ := 10;

writeln('the value is ', iptr^);

dispose( iptr )

end.

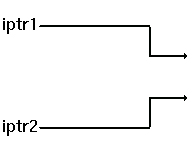

The line

typeint_pointer = ^integer;

declares a new type of variable called int_pointer, which is a pointer (denoted by ^) to an integer.The line

variptr : int_pointer;

declares a working variable called iptr of type int_pointer. The variable iptr will not contain numeric values, but will contain the address in memory of a dynamically created variable (by using new). Currently, there is no storage space allocated with iptr, which means you cannot use it till you associate some storage space to it. Pictorially, it looks like,

The line

new( iptr );

creates a new dynamic variable (ie, its created when the program actually runs on the computer). The pointer variable iptr points to the location/address in memory of the storage space used to hold an integer value. Pictorially, it looks like,

The line

iptr^ := 10;

means go to the storage space allocated/associated with iptr, and write in that storage space the integer value 10. Pictorially, it looks like,

The line

dispose( iptr )

means deallocate (free up) the storage space allocated/associated with iptr, and return it to the computer system. This means that iptr cannot be used again unless it is associated with another new() statement first. Pictorially, it looks like,

POINTERS

Pointers which do not reference any memory location should be assigned the value nil. Consider the following program, which expands on the previous program.

program pointers2( output );

typeint_pointer = ^integer;

variptr : int_pointer;

begin

new( iptr );

iptr^ := 10;

writeln('the value is ', iptr^);

dispose( iptr );

iptr := nil;

if iptr = nil

then writeln('iptr does not reference any variable')

else

writeln('The value of the reference for iptr is ', iptr^)

end.

The line

iptr := nil;

assigns the value nil to the pointer variable iptr. This means that the pointer is valid and stil exists, but it does not point to any memory location or dynamic variable. The line

if iptr = nil

tests iptr to see if its a nil pointer, ie, that it is not pointing to a valid reference. This test is very useful and will come in use later on when we want to construct more complex data types like linked lists.

POINTERS

Pointers of the same type may be equated and assigned to each other. Consider the following program

program pointers3( output );

typeint_pointer = ^integer;

variptr1, iptr2 : int_pointer;

begin

new( iptr1 );

new( iptr2 );

iptr1^ := 10;

iptr2^ := 25;

writeln('the value of iptr1 is ', iptr1^);

writeln('the value of iptr2 is ', iptr2^);

dispose( iptr1 );

iptr1 := iptr2;

iptr1^ := 3;

writeln('the value of iptr1 is ', iptr1^);

writeln('the value of iptr2 is ', iptr2^);

dispose( iptr2 );

end.

The lines

new( iptr1 );

new( iptr2 );

creates two integer pointers named iptr1 and iptr2. They are not associated with any dynamic variables yet, so pictorially, it looks like,

The lines

iptr1^ := 10;

iptr2^ := 25;

assigns dynamic variables to each of the integer variables. Pictorially, it now looks like,

The lines

dispose( iptr1 );

iptr1 := iptr2;

remove the association of iptr1 from the dynamic variable whose value was 10, and the next line makes iptr1 point to the same dynamic variable that iptr2 points to. Pictorially, it looks like,

The line

iptr1^ := 3;

assigns the integer value 3 to the dynamic variable associated with iptr1. In effect, this also changes iptr2^. Pictorially, it now looks like,

The programs output is

the value of iptr1 is 10

the value of iptr2 is 25

the value of iptr1 is 3

the value of iptr2 is 3

SUMMARY OF POINTERS

A pointer can point to a location of any data type, including records. Its basic syntax is,

type Pointertype = ^datatype;

var NameofPointerVariable : Pointertype;

The procedure new allocates storage space for the pointer to use

The procedure dispose deallocates the storage space associated with a pointer

A pointer can be assigned storage space using new, or assigning it the value from a pointer of the same type (eg, iptr1 := iptr2; )

A pointer can be assigned the value nil, to indicate that it is not pointing to any storage space

The value at the storage space associated with a pointer may be read or altered using the syntax

NameofPointerVariable^

A pointer may reference a type which has not yet been created (this will be covered next)

POINTERS: Referencing data types that do not yet exist

The most common use of pointers is to reference structured types like records. Often, the record definition will contain a reference to the pointer,

type rptr = ^recdata;

recdata = record

number : integer;

code : string;

nextrecord : rptr

end;

var currentrecord : rptr;

In this example, the definition for the field nextrecord of recdata includes a reference to the pointer of type iptr. As you can see, rptr is defined as a pointer of type recdata, which is defined on the next lines. This is allowed in Pascal, for pointer types. Using a definition of recdata, this will allow us to create a list of records, as illustrated by the following picture.

In this case, a list is simply of number of records (all of the same type), linked together by the use of pointers.

POINTERS

Lets construct the actual list as shown below, as an example.

program PointerRecordExample( output );

type rptr = ^recdata;

recdata = record

number : integer;

code : string;

nextrecord : rptr

end;

var startrecord : rptr;

begin

new( startrecord );

if startrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('1: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.number := 10;

startrecord^.code := 'This is the first record';

new( startrecord^.nextrecord );

if startrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('2: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.number := 20;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.code := 'This is the second record';

new( startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord );

if startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('3: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.number := 30;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.code := 'This is the third record';

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord := nil;

writeln( startrecord^.number );

writeln( startrecord^.code );

writeln( startrecord^.nextrecord^.number );

writeln( startrecord^.nextrecord^.code );

writeln( startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.number );

writeln( startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.code );

dispose( startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord );

dispose( startrecord^.nextrecord );

dispose( startrecord )

end.

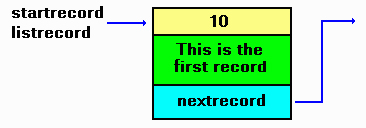

The lines of code

new( startrecord );

if startrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('1: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.number := 10;

startrecord^.code := 'This is the first record';

create the beginning of the list, which pictorially looks like,

The lines of code

new( startrecord^.nextrecord );

if startrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('2: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.number := 20;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.code := 'This is the second record';

link in the next record, which now looks like,

The lines of code

new( startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord );

if startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('3: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.number := 30;

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.code := 'This is the third record';

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord := nil;

link in the third and final record, also setting the last nextrecord field to nil. Pictorially, the list now looks like,

The remaining lines of code print out the fields of each record.

POINTERS

The previous program can be rewritten to make it easier to read, understand and maintain. To do this, we will use a dedicated pointer to maintain and initialise the list, rather than get into the long notation that we used in the previous program, eg,

startrecord^.nextrecord^.nextrecord^.number := 30;

The modified program now looks like,

program PointerRecordExample2( output );

type rptr = ^recdata;

recdata = record

number : integer;

code : string;

nextrecord : rptr

end;

var startrecord, listrecord : rptr;

begin

new( listrecord );

if listrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('1: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord := listrecord;

listrecord^.number := 10;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the first record';

new( listrecord^.nextrecord );

if listrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('2: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

listrecord := listrecord^.nextrecord;

listrecord^.number := 20;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the second record';

new( listrecord^.nextrecord );

if listrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('3: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

listrecord := listrecord^.nextrecord;

listrecord^.number := 30;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the third record';

listrecord^.nextrecord := nil;

while startrecord <> nil do

begin

listrecord := startrecord;

writeln( startrecord^.number );

writeln( startrecord^.code );

startrecord := startrecord^.nextrecord;

dispose( listrecord )

end

end.

In this example, the pointer listrecord is used to create and initialise the list. After creation of the first record, it is saved in the pointer startrecord. The lines of code

new( listrecord );

if listrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('1: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

startrecord := listrecord;

listrecord^.number := 10;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the first record';

creates the first record and initialises it, then remembers where it is by saving it into startrecord. Pictorially, it looks like,

The lines of code

new( listrecord^.nextrecord );

if listrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('2: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

listrecord := listrecord^.nextrecord;

listrecord^.number := 20;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the second record';

add a new record to the first by linking it into listrecord^.nextrecord, then moving listrecord to the new record. Pictorially, it looks like,

The lines of code

new( listrecord^.nextrecord );

if listrecord^.nextrecord = nil then

begin

writeln('3: unable to allocate storage space');

exit

end;

listrecord := listrecord^.nextrecord;

listrecord^.number := 30;

listrecord^.code := 'This is the third record';

listrecord^.nextrecord := nil;

add the last record to the previous by linking it into listrecord^.nextrecord, then moving listrecord to the new record. Pictorially, it looks like,

Note how much easier the code looks than the previous example.

POINTERS