Image courtesy Yakima Valley Museum |

Image courtesy Yakima Valley Museum |

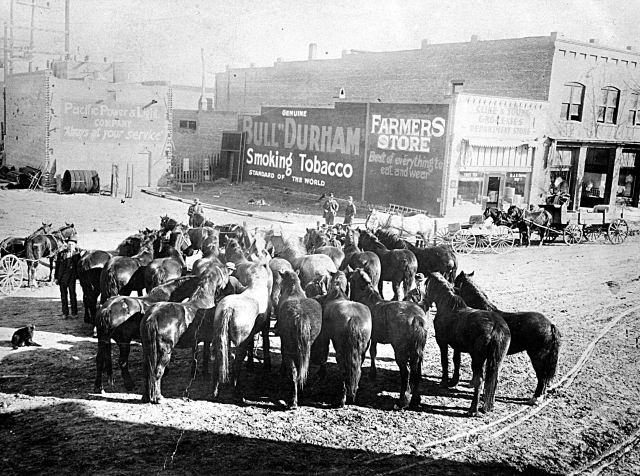

A Long PartnershipSince time immemorial, horses have been an indispensable part of Yakama culture. For centuries they were the primary means of transportation for all tribal members, a daily companion for most, a measure of wealth for many, and a source of legends and songs. So long as anyone can remember, the Yakama were renown for their horses and their horsemanship. |

Image courtesy Yakima Valley Museum |

Times, They ChangeThe influx of explorers and settlers into the Washington territories that began in the early 1800ís created a ready market for Yakama horses that lasted for decades. After the Treaty of 1855, the number of horses on the Yakama Reservation gradually increased from several hundred to tens of thousands. Because of their high value, horses were carefully managed and thus created few environmental problems when compared to those caused by the large numbers of cattle and sheep in the area. At the beginning of the 20th century there were very few truly wild horses on the Yakama Reservation. |

Image courtesy Yakima Nation Museum |

Quickly Out of FavorThe introduction of gasoline powered vehicles in the early 1900s forever changed the relationship between the Yakama people and their horses. As people throughout the area turned to cars and trucks for their transportation, horses were no longer essential. Consequently, their economic value decreased rapidly. Unable to support large numbers of horses, tribal and non-tribal people throughout central Washington released horses of all breeds onto the land. Some of the feral horses migrated into the closed portions of the Reservation where they were able to survive and reproduce. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

Feral to WildAs the human population increased on and around the Yakama Reservation, progeny of the feral horses were forced onto uninhabited land; portions of the Reservation that were unfit for agriculture or economic development. The largest of these areas was along Logy Creek and Dry Creek west of US Highway 97 and extending into the foothills of the Cascade Mountains. After many generations of adaptation to this harsh environment, the wild horses were able to thrive where few other animals could. With no major predators their numbers began tp increase rapidly. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

The Unseen ManyToday only a small number of people, either tribal or non-tribal, are aware that several thousand (perhaps as many as 6,000) wild horses roam freely across the Yakama Reservation between Yakima and Goldendale. Despite their numbers, very few people have any direct connection to these horses. Consequently, the plight of the Yakama wild horses is a story that is virtually unknown even among tribal members. The increasing number of horses and a lack of any effective procedures to control this increase is creating conditions that will significantly impact Yakama culture and economics for generations to come. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

No Longer Just SurvivorsDespite the fact that the wild horses have been confined to the driest, rockiest, and least desirable parts of the Reservation for nearly a century, they have not only managed to survive in this hostile environment but they are now increasing at an alarming rate. It is estimated that the reproductive/survival rate of the wild horse herds is somewhere between 20 and 30 percent per year. At this rate, the current population of nearly 6,000 animals will double to more than 12,000 animals in approximately three years. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

Environmental ImpactsStudies by Yakama Nation wildlife biologists indicate that lands now available to the wild horses can sustain a permanent population of around 1,000 animals without generating major long-term consequences. As the horse population increases above this number the more serious and the more diverse the environmental problems will become; for the horses, for the land, for all the other creatures that share the land, for salmon in streams within the affected areas, and ultimately, for the Yakama Nation. At some point dealing with significant horse-generated environmental problems will be unavoidable. With a population that is already 5-6 times above the sustainable level, significant problems are already apparent in areas where the horse population is highest. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

Where Have All The Grasses Gone?Throughout most of the horse-dominated areas of the Reservation, native bunch grasses have been unable to withstand severe overgrazing and have been replaced by the highly-invasive annual cheat grass. Although cheat grass provides horses with lush growth during late winter and early spring, the plants flower and die by early summer leaving the area brown and dry. Heavy year-around grazing of this dry landscape by increasing numbers of horses has resulted in large areas that are kept nearly devoid of edible plants for several months each year. Water and wind erode these areas and deposit the sediment into streams that are essential to spawning salmon on a large portion of the Reservation. As the horse population increases significant damage is also increasing in traditional root digging areas. |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

Horse ChasingBecause the wild horses live in remote portions of the Reservation where access is difficult, very few individuals have the opportunity to observe wild horses in their native habitat. Wildlife biologists of the Yakama Nation and a few tribal horse chasers are trying to reduce the wild horse population by capture and removal. Captured horses are sold to a variety of willing buyers. However, the numbers of animals that have been removed in recent years is far fewer than the annual increase in population. Consequently, horse numbers continue to increase year after year. Current economic factors that include high operations costs and depressed market prices are doing little to encourage large-scale horse removal as a means of population control |

Photo Gaylord Mink |

The Solution Remains ElusiveIn 2008 Tribal Council approved the first comprehensive, community-based wild horse management plan ever designed to return the wild horse population back to a long-term sustainable level. However, this plan has yet to be adequately funded. Until funds are available for large scale animal removal, environmental problems that are associated with the exploding wild horse population will become more acute and the solutions will become much more difficult to achieve. Thus is the dilemma of the Yakama and their wild horses. |