|

||

|

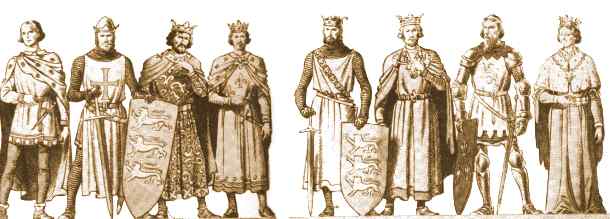

TIME LINE 1154 - 1399 |

|

1154 - 1189 |

1189 - 1199 |

1199 - 1216 |

1216 - 1272 |

1272 -1307 |

1307 - 1327 |

1327 - 1377 |

1377 - 1399 |

The Plantagenet kings, were the descendants of Geoffrey of Anjou, father of King Henry II., who married Queen Matilda in the year 1127. Plantagenet, is the surname first adopted by Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, and is said to have originated from his wearing of a branch, or broom (plants de genêt) in his cap. The, name was borne by the fourteen kings, from Henry II. to Richard III, who occupied the English throne from 1154 -1485.

Henry II. found far less difficulty in restraining the license of his barons than in abridging the exorbitant privileges of the clergy, who claimed exemption not only from the taxes of the state, but also from its penal enactment's, and who were supported m their demands by the primate Becket. The king's wishes were formulated in the Constitutions of Clarendon (1164), which were at first accepted and then repudiated by the primate, The assassination of Becket, however, placed the king at a disadvantage in the struggle ; and after his conquest of Ireland (1171) ho submitted to the church, and did penance at Becket's tomb. Henry was the first who placed the common people of England in a situation which led to their having a share in the government. The system of frank-pledge wee revived, trial by jury was instituted by the Assize of Clarendon, and the Eyre courts were made permanent by the Assize of Nottingham. To curb the power of the nobles he granted charters to towns, freeing them from all subjection to any but himself, thus laying the foundation of a new order in society.

Richard I., called Coeur de Lion, who in 1189 succeeded to his father, Henry II., spent most of his reign away from England. Having gone to Palestine to join in the third crusade he proved himself an intrepid soldier. Returning homewards in disguise Through Germany, he was made prisoner by Leopold, duke of Austria, but was ransomed by his subjects. In the meantime John, his brother, had aspired to the crown, and hoped, by the assistance of the French to exclude Richard from his right. Richards presence for a time restored matters to some appearance of order; but having undertaken an expedition against France, be received a mortal wound at the siege of Chalons, in 1199.

John was at once recognized as King of England, and secured possession of Normandy; but Aujou, Maine, and Touraine acknowledged the claim of Arthur, son of Geoffrey, second son of Henry II. On the death of Arthur, while in John's power, these four French provinces were at once lost to England. John's opposition to the pope in electing a successor to the see of Canterbury in 1205 led to the kingdom being placed under an interdict; and the nation being in a disturbed condition, he was at last compelled to receive Stephen Langton as archbishop, and to accept his kingdom as a fief of the papacy (1213). His exactions and misgovernment had equally embroiled him with the nobles. In 1213 they refused to follow him to France, and on his return defeated, they at once took measures to secure their own privileges and abridge the prerogatives of the crown. King and barons met at Runnymede, and on June 15, 1215, the Great Charter (Magna Charta) was signed. It was speedily declared null and void by the pope, and war broke out between John and the barons, who were aided by the French king. In 1216, however, John died, and his turbulent reign was succeeded by the almost equally turbulent reign of Henry III.

During the first year of the reign of Henry III. the abilities of the Earl of Pembroke who was regent until 1219, retained the kingdom in tranquility; but when, in 1227, Henry assumed the reins of government he showed himself incapable of managing them. The Charter was three times reissued in a modified form, and new privilege, were added to it but the king took no pains to observe its provisions. The struggle, long maintained in the great council (hence-forward called Parliament) over money grants and other grievances reached an acute stage in 1263, when civil war broke out. Simon de Montfort who had laid the foundations of the House of Commons by summoning representatives of the shire communities to the Mad Parliament of 1258, had by this time engrossed the sole power. He defeated the king and his son Edward at Lewes in 1264, and in his famous parliament of 1265 still further widened the privileges of the people by summoning to it burgees as well as knights of the shire. The escape of Prince Edward, however, was followed by the battle of Evesham (1265), at which Earl Simon was defeated and slain, and the rest of the reign was undisturbed.

On the death of Henry III., in 1272, Edward I. succeeded without opposition. From 1276 to 1284 he was largely occupied in the conquest and annexation of Wales which had become practically independent during the barons' wars. In 1292 Balliol, whom Edward had decided to be rightful heir to the Scottish throne, did homage for the fief to the English king; but when, in 1294, war broke out with France, Scotland also declared war. The Scots were defeated at Dunbar (1296), and the country placed under an English regent; but the revolt under Wallace (1297) was followed by that of Bruce (1306), and the Scots remained un-subdued. The reign of Edward was distinguished by many legal and legislative reforms, such as the separation of the old king's court into the Court of Exchequer; Court of King's Bench, and Court of Common Pleas, the passage of the Statute of Mortmain . In 1295 the first perfect parliament was summoned, the clergy and barons by special writ, the commons by writ to the sheriffs directing the election of two knights from each shire, two citizens from each city, two burghers from each borough. Two years later the imposition of taxation without consent of parliament was forbidden by a special act (De Tallagio non Concedendo). The great aim of Edward, however, to include England, Scotland, and Wales in one kingdom proved a failure, and he died in 1307 marching against Robert Bruce.

The reign of his son Edward

II. was unfortunate to himself and

to his kingdom. He made a feeble attempt to carry out his father's last and earnest request to prosecute the war

with Scotland, but the English were almost constantly unfortunate; and at length, at Bannockburn (1314), they received

a defeat from Robert Bruce which ensured the independence of Scotland. The king soon proved incapable of regulating

the lawless conduct of his barons; and his wife, a woman of bold, intriguing disposition, joined in the confederacy

against him, which resulted in his imprisonment and death in 1327.

The reign of Edward

III. was as brilliant as that of

his father had been the reverse. The main project. of the third Edward were directed against France, the crown

of which he claimed In 1328 in virtue of his mother, the daughter of King Philip. The victory won by the Black

Prince at Crecy (1346), the captors of Calais (1347), and the victory of Poitiers (1356), ultimately led to the

Peace of Brétigny in 1360, by which Edward III. received all the west of France on condition of renouncing

his claim to the French throne. Before the close of his reign, however, these advantages were all lest again, save

a few principal towns on the coast.

Edward III. was succeeded in 1377 by his grandson Richard II., son of Edward the Black Prince. The people of England now began to show, though in a turbulent manner, that they had acquired just notions of government. In 1380 an unjust and oppressive poll-tax brought their grievances to a head, and 100,000 men, under Wat Tyler, marched towards London (1381). Wat Tyler was killed while conferring with the king, and the prudence and courage of Richard appeased the insurgents. Despite his conduct on this occasion Richard was deficient in the vigour necessary to curb the lawlessness of the nobles. In 1398 he banished his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke; and on the death of the latter's father, the Duke of Lancaster, unjustly appropriated his cousin's patrimony. To avenge the injustice Bolingbroke landed in England during the kings absence in Ireland and at the head of 60,000 malcontents compelled Richard to surrender. He was confined in the Tower, and despite the superior claims of Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, Henry was appointed king (1399), the first of the House of Lancaster. Richard was, in all probability, murdered early in 1400.

In 1400 the family was divided into the branches of Lancaster ( Red Rose ), and York ( White Rose ), and from their reunion in 1485 sprang the House of Tudor . The battle of Bosworth was fought in the year 1485; when Richard III., the last of the line of Plantagenet kings, died a period of three hundred and thirty-one years.