Chapter 3: "Goralu Czy Ci Nie Zal..." The Polish Armed Forces Decide.

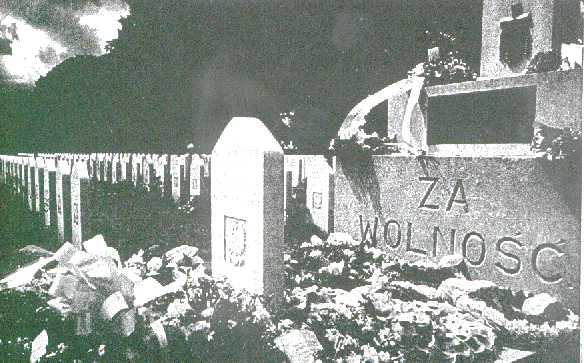

General Sikorski's GraveJust before his return to Poland

General Sikorski's GraveJust before his return to Poland

Whenever Poles of a certain generation meet over a bottle of vodka, they invariably turn to a sentimental song that reminds them of the melancholia of exile a situation with which Poles are only too familiar.

"Goralu, czy ci nie zal,

Odchodzic od stron ojczystych.

Swierkowych lasow i hal,

I tych potokow srebrzystych.

Goralu, czy ci nie zal?

Goralu wracaj do hal!

---

Goral, don't you feel sad,

To leave your own native land.

The pastures and forests of spruce,

And those silvery brooks.

Goral, don't you feel sad?

Goral return to your valley!

The "Goral" of the song, the Highlander of the Polish

Tatra mountains, looks back at his home with tears in his eyes, knowing he will never see it again; a feeling that generations of Poles have, all too often, had to go through.

Polish history, dotted as it is with partitions, revolutions and insurrections, has been the mother of exiles and émigrés; so much so that it is estimated that there are some 15 million Poles and people of Polish extraction living beyond Poland's borders. The three partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th Century led to the emigrations of 1771, 1792 and 1794. The Polish insurrection in 1830 led to what became known as the "Great Emigration" [Wielka Emigracja] and a flood of patriotic outpourings from the leading lights of Polish culture in exile: Chopin, Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Krasinski and Norwid. The failed risings of 1846 and 1848 led to a fresh wave of emigration as did the "January Insurrection" of 1863 - the year of the so-called "Young Emigration" [Mloda Emigracja].

The Polish Armed Forces which found themselves under British command in Northern Europe and the Mediterranean in 1945 were part of a long and unhappy tradition and the dilemma that faced them had been faced by generations of Poles before: to return to Poland or not?

The effects of this new Polish Diaspora are discussed in Poland today in a way that would have been impossible fifty years ago. General Paszkowski, an officer of the "People's" Polish Air Force writes:

"The troops of the Polish Armed Forces in the West were not - unfortunately - permitted to fulfil their dreams of a victorious return, in closed ranks, to a liberated Fatherland. Thousands remained abroad; thousands had to follow a long and difficult road before returning to their country - a country in which more than one of these soldiers had to suffer the bitterness of humiliation and undeserved suffering." [1]

In 1945, however, the Warsaw authorities were not so understanding. It served the new regime's propaganda purposes to paint all those who returned to Poland as patriots and those who did not as bourgeois landowners, 'kulaks' and counterrevolutionaries with no interest in the welfare of Poland. As one repatriate wrote:

"To return or not to return? This dilemma split our Army into two camps. In the first rank of those who decided to remain belonged those whom the revolution in Poland had seized their estates and fortunes." [2]

Many of the Poles who returned to Poland were full of criticism of their officers - for that matter many of the Poles who did not return were filled with the same allegations of self-service and corruption.

"Towns were crumbling into ruins, people were dying by the thousand, the fate of the world was hanging on a hair yet the Poles in London were doing everything except what they should have been doing. The pilots were dying - let them die; brave lads. The Army - lovely boys - was going into battle. Orders; fine words; crosses. In the offices where these orders were printed sat such types - so much bickering; so much filth and nothing else." [3]

Even Colonel Kuropieska, whose writing is marked by its very reasonableness, comments that of all the Polish officers the worst were in Britain. Many had been given no command or had fallen into disfavour and had been, as the Colonel put it, "discarded" [wybrakowani]. [4]

One former Polish soldier, Jean Carrer, puts forward a criticism that was often made by men who had seen service with the AK in Poland and had then made their way to London. These men...

"...bitterly complained of the behaviour of even high ranking officers in London. There was no comparison between their comrades-in-arms in the Wilno AK and those who surrounded them in the London staff. The Wilno AK were filled only by highly motivated soldiers, ready to serve and die for their country. They did not join the AK to receive a promotion or a salary, because neither was given often. The London staff frequently consisted of the people who were not fit for the front-line service or whose motivation was to have a good time." [5]

This criticism goes beyond a mere question of personality. Some have gone as far as to claim a conspiracy between the British Government and the Polish High Command. Kazimierz Kozniewski, writing in Warsaw in 1960, questioned the motives of the "London" Poles:

"In 1945 or 1946 all of them could have returned. They chose emigration; they gave way to the determined propaganda of the so-called "London" camp, members of the former Polish Government who, disregarding the good of the country needing hands for reconstruction and disregarding the personal tragedy of family separation, unleashed a campaign against the returnees stamping them as traitors. For many families this decision to stay in emigration has been the source of great tragedy and a tragedy that is still alive today. It is difficult to determine how many of those who stayed abroad regret their decision. The "London" politics are today finally bankrupt but its fruit remains in the form of several thousand Poles living in a new emigration." [6]

General Machalski, former military attaché to Turkey, was no less equivocal in his condemnation of the "London" camp of which he was, nominally at least, a member. It was clear the British were having trouble dealing with the Poles so, Machalski alleges, they bribed the Poles into submission.

"So they [the British] had a different idea. They invited the elders of the Polish General Staff to London and bought them like some Negro cacique. For the price of a lifelong general's pension they agreed to lay down their arms and send their unarmed soldiers to England." [7]

Having said this there was still a desire to return to Poland from the rank and file of the Poles - a desire that could not be quelled by the promise of exile and a British passport. As one Cadet Officer wrote:

"The Prime Minister Churchill wants to give us the British citizenship after the war. I appreciate this, but it wasn't the reason we opposed the Germans. Whether this would mean that Mr Churchill doesn't believe in his own word that Poland would be really free and independent country." [8]

The campaign run by the Poles who opposed repatriation to Poland was particularly bitter and vitriolic and, on occasion, deadly. Reactions depended very much on the individuals approach to the events in Poland. Linowski, for example, complained that it created for itself...

"...a false picture of Poland expounding and exaggerating every negative aspect associated with the process of revolutionary change that was taking place in the country." [9]

Mrowiec continues this theme:

"Our country was described as a Soviet training ground in which Polish women were being raped, in which the Polish language was being blunted and in which churches were being turned into barracks or 'houses of immorality'. Speeches, discussions, articles and military orders were all poisoned by a hatred of those who in Poland were turning castles and palaces into sanatoria and rest homes. It has to be admitted that the cancer of doubt and uncertainty began to eat at the heart of more than one soldier who could not come to an independent and objective view of the situation." [10]

The Dzierzynski Academy of Military Politics published a similar denunciation in 1967:

"The Soviet Union was portrayed in the worst possible light, usually by way of generalised slander. So, for example, by using all available means, the lie was spread that the Red Army, entering Poland, was murdering old people and children and was deporting people en masse to Siberia or enlisting them into its ranks. With the help of its press it published news of the alleged raping of Polish women and, continuing the line, of their subsequent suicides.

In the area of anti-Soviet propaganda the propaganda bureau of the 2nd Corps was not even surpassed by Goebbels' Propaganda Ministry. The propaganda was so acute that even the British had to take an interest in the matter." [11]

The substance of these "lies" and "slanders" are dealt with in the next chapter. Rutkowski is, however, correct in saying that the British took an interest in Polish produced propaganda and for that matter the propaganda that was reaching the Poles from outside.

In Italy both the Germans and the Polish Provisional Government broadcast its message over the airwaves to the Polish forces. This radio war became known as the "war of the Wandas" as the German "Radio Wanda" vied with "Radio Kosciuszko", sponsored by Wanda Wasilewska in Poland, to get its message across. Whereas few believed the words that were broadcast from Poland it was more difficult to ignore the Germans. As Melchior Wankowicz, a respected war-correspondent, admitted: although "Radio Wanda" told a lot of lies it told a lot of truth as well, especially about the situation in Poland. [12]

This was brought to the attention of the War Office and in April, 1944, AFHQ issued a memo to the Polish Base Censor to pick out any references to German radio broadcasts like the one from a Private in June:

"We can believe this time what says German Radio that NKVD arrests, kills or deports the Polish population who did not resist actively the German: This is the truth for the Russian motto - "Who is not with us is against us". The West is silent and commands to be silent in order not to endanger itself to his Ally." [13]

The Foreign Office were equally concerned to counter this German propaganda that seemed to be having a harmful impact on the Poles. For the troops in Italy new short-wave bands were set up and in Scotland a new medium-wave band was launched so that the BBC could 'explain' events in Poland. [14] The Poles had a surfeit of information but very little could be deemed as balanced. The BBC would not say anything critical of the Soviet Union - a fact that rankled with the Poles and, what was worse, often expounded the Soviet viewpoint while the British censored the Polish military press. The Germans were rubbing salt into Polish wounds with constant carping about Katyn, and the "bloody hordes of Stalin" entering Poland - they even had a leaflet campaign [see Appendix D] and while the Poles secretly, and sometimes even openly, knew much of what they were saying was true, it went against the grain to agree with the Nazis. The Communist broadcasts from Poland were the least convincing simply because its message of revolution was too hostile for its audience. The Polish Base Censor picked up the comments of one officer:

"I listen sometimes to the Russian broadcast in Polish. They speak in such vile manner about our government and about our political chiefs. It is funny but I found out from the Russian news that we Polish troops in Italy are Nazi and we don't want to fight with the Allied troops against Jerries." [15]

This "fascist" label that had been given to the Poles in the West was not only inaccurate but also offensive to the Poles, even to many who had returned to Poland. Bernard Newman recalls a conversation with one such repatriated Polish soldier:

"I was captured by the Germans in Italy, got away when they collapsed, and am now in the Polish Army again - in Poland. It worries me - and makes me mad - when I hear some of our bosses talking about General Anders as a fascist. After all, he was fighting the fascists while these people were sitting pretty in Moscow. I fought at Tobruk and Cassino, I suppose that is fascist?" [16]

The two principle allegations laid by Warsaw and Moscow against the Poles in the West was that, firstly, they did not want to fight against the Germans, as in this article from Moscow's "Pravda" of February, 1944:

"The émigré Polish Government and its servants wage no fight against the Germans, do not wish to wage it and cannot wage it...

The émigré Polish Government, which includes fascist political cheap jacks, has lost all sense of reality. It lives in a phantom world of Hitler mirage. It has completely severed itself from the real Polish peoples, who are waging a relentless struggle against the German invaders and their Polish assistants. The London Polish political cheap jacks have nobody to back them in Poland except the pro-fascist agencies which are helping the Germans, and the simpletons they have misled.

All Poles who value Poland's honour and independence march with the "Union of Polish Patriots" in the USSR." [17]

The second assault on the Poles is that they actively collaborated with pro-Nazi elements - in particular the Chetniks in Yugoslavia. How far the Chetniks were pro Nazi as opposed to anti-Communist is today a moot point, yet at the time any association with the Mihailovich Chetniks was enough to tar the Poles with the epithet of fascists. Colonel Sidor wrote of the mutual co-operation between Anders and the Chetniks and noted that after the execution of General Mihailovich special masses were said by the chaplains of 2 Polcorps. [18] The Tito regime was not above complaining about the Poles and its influence among the anti-Communist opposition. It complained to the Foreign Office in February 1946:

"The Polish Emigrants Army is in close touch with the groups of Quisling formations, which are at present in Italy, in particular the Ustashi (Croat terrorists). In Italy these Quisling groups enjoy the material support of General Anders' Army." [19]

The Foreign Office steadfastly refused to rise to Warsaw's bait. Since the Yugoslavs had produced no evidence for their allegations so they had to be discounted. Czerkawski recounts the story of Boleslaw Rozek who was escorting war criminal Ante Pavelic to Trieste to stand trial in Yugoslavia. Instead of thanks, he was called a "Polish fascist from Anders' fascist army". [20] This came as something of a culture shock to Rozek.

The propaganda that was issued by those advocating non-return to Poland proved to be highly successful. The fact that so many Poles did go back gives testimony to the power of homesickness rather than to them being won over by the pronouncements of Warsaw. The fact that so many Poles did not go back shows just how much fear had been put in the minds of the individual soldier.

"Less happy, but for that more damaging, was the propaganda designed to frighten those who wished to return to their country. They continued to announce through megaphones that those who went back would be sent to the 'land of the Polar bear'. Obviously the British wanted as many Poles as possible to stay as their guests. The contents of letters that were received from Poland were varied: some encouraged return others warned against it. As it turned out the letters of this second category often came from the wives of soldiers who had started new lives with other men. At night there were lively discussions on this subject. Some people had nervous breakdowns as a result." [21]

Dzikiewicz, himself a repatriate, is quite wrong in his assertion that the propaganda not to return came from the British, in fact nothing could be further from the truth. The point he makes about the mental anguish the propaganda caused is, however, a valid one.

There were many reports of suicide among the Polish Forces and among the Displaced Persons scattered across Europe. One account from Camp Kaefertal in Germany reports that as 1,600 Polish former POWs were being repatriated to Poland, one of the officers took out his revolver and shot himself. [22] Another report from Brazil was the case of Edward Kurdziel who had been in Rio since June, 1946, but had only found a low paid job. Kurdziel had gone to the British Embassy in November to see the trade attaché for help. As the attaché left the room to ring a Polish company in Brazil, Kurdziel shot himself in the chest "in a fit of depression and helplessness". The story made the Rio press and was picked up by the Warsaw Ministry of Information and Propaganda who claimed, with some accuracy, that the British were trying to keep the whole story as quiet as possible. According to the FO report on the event the local papers in Rio had...

"...expressed annoyance that they were unable to obtain full information from the Press Section of the Police Headquarters and suggested that an undue amount of respect was being shown for foreign diplomatic privilege." [23]

The FO minute to the report stated: "I don't think any action is called for. Luckily the press here has not, so far as I know, mentioned the incident." The conclusion was that, obviously, the man had been "mentally unbalanced" as it was unlikely he had chosen the embassy for his demise. Furthermore, it was not the responsibility of the British Government to look after the Poles once they were abroad and out of the armed forces. The Poles "...should go to the Warsaw people with their troubles... which they refused to do."

In January, 1947, the "West Sussex County Times" ran a story that Karl Pazdziernick [sic] had been found hanging from a tree at Mannings Heath Golf Club. "Evidence was given that he was worried at not being able to rejoin his wife in Germany." [24]

Despite the mental anguish the propaganda caused, it continued unabated. The disillusioned Gen. Machalski continues:

"Gen. Anders, for whom there was no road to Poland, had seen his world turn upside-down so he commenced a hysterical propaganda against returning home. Sick people who had volunteered for repatriation were brutally thrown out of hospital, the healthy were isolated in special camps, the infected had to be separated. This violent propaganda had its results as a sizeable number of soldiers decided against returning." [25]

Reading the official pronouncements from the General Staff today they do not appear unreasonable. Certainly they appealed to the soldiers sense of patriotism and sense of history, General Sosnkowski, the former Polish C-in-C, said in a speech:

"What have the Poles been dying for the last five years? In whose name have the rivers of our blood covered the ground in Italy? The Carpathian and Kresowa Divisions, the Lwowska Brigade and the Wilenska Brigade.... They did not think of themselves or about some internal quarrel when they fell like corn cut with a scythe. They were faithful and modest soldiers whom death had made equal. They died with the name of the Fatherland on their lips and with a faith in its future.[...]

They died, as die other soldiers in Poland and abroad, for all of Poland and the future of Poland decided by Polish hands on the Polish land." [26]

General Rudnicki in his Order of the Day on the 6th July, 1945, also made a patriotic appeal to his men after he became GOC 1st Armoured Division:

"Our duty as the Polish occupation Division on German soil, under Allied command, will be accomplished with loyalty and honour. We will one day return to Poland, but only with arms in our hands - to the Poland whom we have dreamt about during the last five years of the war. Poland truly free and independent. We will return to wipe the tears of our women and children, and to ensure that law and justice, and not foreign domination, will reign in Poland.

We will never give up our struggle to free Poland and all the other enslaved nations, and we will live up to our traditional motto, "For your freedom and ours". In this struggle we shall not be alone. Polish soldiers! This is our position, our will, and our decision." [27]

General Anders, the bane of the Foreign Office, was the man most associated with the anti-return campaign. His pronouncements that Poland was under a foreign occupation did little to enhance his popularity with the British but it was the message many Polish troops wanted to hear. Anders' warning to his subordinates was reproduced in the War Diary of the 13 Battn, 5 Kresowa Division:

"Among us we may still find some tired people, some people who are weak, who do not feel they have the strength to go with us on our journey which must eventually lead to victory but will still present us with more than one problem. We will not keep anyone in our army by force" General Anders underlines in all his speeches that anyone who volunteers for repatriation to Poland must be either physically or mentally ill because no one else would willingly return to Poland under a foreign government. We do not want sick people amongst us. In our particular situation the value of an army is judged more by the quality of its men rather than the number and General Anders does not want any soldier who returns to Poland and then meets some miserable fate to be able to say that he had not been warned in time by his Commanding Officer. The General further states that from the moment our erstwhile colleague volunteers for return and he is sent off to the Allied transit camp the General would take no further responsibility for his fate.

Our newest colleagues who came to us, throwing away their German uniforms, were recognised and are continued to be recognised as good Poles. To the Soviet authorities they will be, above all, "fascists", "Volksdeutsche", "Spies", "deserters", etc. etc. We know from personal experience what the Soviet authorities do with those who are inconvenient to them. If anyone thinks they will return to Poland and see their family and then find themselves in the heart of Russia let them have no pretensions to us." [28]

Another of Anders' warnings read:

"We considered and continue to consider them as good Poles. We will not stop them from taking this step. They have a free decision to either stay with us or to go where terror reigns to be persecuted by a foreign occupation." [29]

As a 'them and us' situation developed, so it threatened to spiral out of control. Some of the less political Generals recognised that the group that gained the label of "Communists" were in serious danger. General Sosabowski, former GOC Polish Parachute Brigade, writes that the title of "Communists" came not only from the rank and file but from certain officers. The relationship between these officers and the future repatriates became so bad that it often became necessary to separate them. [30]

The Warsaw authorities were well aware of what was happening in the Polish camps but were powerless to intervene. Warsaw's military missions constantly complained about the attitude of those Poles who did not want to return to Poland and of their treatment towards those who did. One report states:

"Today this soldier - this faithless one [sprzeniewierca] - to his commanders and to his, up to this point, friends; to his comrades in arms with whom he shared the pain of battle at Monte Cassino and Falaise, at Tobruk and Narvik, has become a leper. Because he is returning to his country he has at once stopped being a patriot." [31]

Lt Proczka, another of Warsaw's men in Italy, wrote to his superiors complaining about the treatment of possible repatriates in DP camps at Barletta and Trani that were run by the Polish 2nd Corps. Men from the Corps were using pressure to discourage return. In particular, posters had been put up all over the camp showing a mouse in Italy looking at a mousetrap in Poland. Since the camp had been "hermetically sealed off" by Anders' men, so only their views were being put forward. Proczka also complained that the UNRRA camp at Bari and the repatriation camp at Regio Emilia were also under the influence of Anders. He complained that special hit squads were coming from Bologna and Modena to work on those who might be wavering. [32]

Zygmunt Boger, a Pole who had served in the German Army and found himself under pressure in his POW camp, recounts:

"Every Saturday, between 10 and 12 in the morning we would form a horseshoe on the barrack parade ground and a jeep with a megaphone would drive up and someone from Anders' army would speak to us. He would tell us that there was no use in us thinking about returning to Poland, that Poland was a subject country dependent on the Soviet Union...." [33]

The theme that Poland was a vassal state to Moscow was hotly denied by Warsaw's people. Dr Prawin, head of the Polish Mission in Berlin, told representatives of the British FO that he thought it was undesirable for the British "...to treat Poland as [a] mere adjunct of the Soviet Union". To which Hankey minuted: "Cordially support his last point." [34] This, not surprisingly, was not a view shared by Anders:

"Our country, deprived of the rights of speech, looks towards us. It wishes to see us in the land of our ancestors - to that end we are striving and longing from the bottom of our hearts - but it does not want to see us as slaves of a foreign force: It wants to see us with our banners flying as forerunners of true freedom. As such a return is impossible today, we must wait in closed and disciplined ranks for a favourable change of conditions." [35]

Anders was well aware of the unusual position he and his soldiers found themselves in. The post-war paradox was that while all the other armies in the world were anxiously awaiting demobilisation, the Poles wanted to keep their forces intact [36], although some did find the situation rather perplexing. Edmund Thielmann relates his feelings at the situation he was in:

"The war was long over and still our position was unclear. The émigré propaganda did everything it could to create confusion and doubt in our minds so as to impede our making a decision about returning to Poland. We were disorientated.

- What do you think about the growth in the number of soldiers? - I asked Ireneusz.

- Someone has to keep the Japanese down. Don't worry yourself, Polish cannon-fodder is still valuable - he answered." [37]

Thielmenn could not understand why the Polish forces were being upgraded - for example the 2nd Armoured Brigade was raised to a Division and the 14th Armoured Brigade was brought into service. It all seemed very strange to him. Eventually Thielmann volunteered for repatriation and went back to Poland.

There was a darker side to the campaign against returning to Poland. Those who volunteered often had to suffer the indignity of being ostracised by their comrades. Tadeusz Kochanowicz writes that after he had made his decision to return he was told that no one would have anything to do with him and he would be treated like a man infected with gonorrhoea. [38] The fact that men volunteering to go back to Poland had to sit at separate tables so as not to "infect" others was a minor inconvenience compared to the reports of men being attacked after requesting repatriation. Mrowiec reports that a group of these "excommunicated" soldiers were being driven by road from San Basilia to the Cervinara repatriation camp when, on a certain bend in a mountain pass, the driver jumped out of the vehicle leaving it to plummet over the edge. [39] Many soldiers decided it would be safer to wait until the 2nd Corps was brought to the UK before requesting repatriation. At least in Britain the matter would not be so dependent on the largess of the "Anders clique". Although Mrowiec has few kind words to say about his Polish commanders, he gives grudging praise to the British saying: "It has to be admitted, however, that the British authorities looked after us with great care and equipped us well for our return to Poland"

One of the popular metaphors used at the time to address the issue of repatriation was that of a railway journey. Nowakowski, in his "At the railway stop" [Na Przystanku], explained that, whereas some Poles would be catching the train back to Poland, most would not and would have to wait at the station. Maybe one day their train would arrive. [40]

The commemorative album of the Polish Parachute Brigade continues this theme:

"Our mutual road, the road we have all followed to a free Poland, remains the same - only we will no longer travel it together. Some will return to Poland sooner, others later. Each of us will decide, according to his own conscience, when the right moment to return is. [...]

Those who leave us now will leave us as brothers. We will shake hands, thank each other for our mutual effort and look in each others eyes. This open look will conform our complete mutual respect. The aim that binds us in our separation remains the same: A free and independent Fatherland." [41]

The pronouncements from the Parachute Brigade are typical of the style emanating from the Polish Forces in Germany - a style less extreme than those in Italy. The 1st Armoured Division had not been through the Soviet prison system like so many in the 2nd Corps and so viewed the Soviet Union in a different light. Even Warsaw's Academy of Military Politics recognised the difference:

"It must be said that despite the grief at losing the land in the East, and in contrast to the Polish Second Corps, the 1st Armoured Division still considered that the Germans were Enemy Number One - although the USSR was also regarded as an enemy. Regardless of this, however, there was no special anti-Soviet Campaign in the 1st Armoured Division." [42]

General Sosabowski, one of the more moderate members of the Polish High Command, tried to reassure volunteers for repatriation that they were not the pariah some would make out:

"Lads - There seems to have been a misunderstanding here. Who doesn't want to return home? We all want and desire this - those who go back now, and those who have decided not to go back yet. Its just like passengers waiting for a train. Some - that's you, want to be off at all costs on the first available train and some - your comrades, have yet to decide which train to take." [43]

Despite the masses of propaganda and counter-propaganda that was floating about at the end of the war, most Polish soldiers knew whether they were going to return to Poland or not - the information provided by senior officers only served to confirm certain opinions.

The opinion not to go back to Poland was viewed with some sympathy by "The Economist" of August 1946:

"In fairness to them [the Poles] it must be said that their experience is sufficient comment on Mr Bevin's declaration of March 10 [sic - 20th] in which he said that it was the "duty" of the Polish exiles to return and that a Polish memorandum, which no Polish Minister had even troubled to sign, was a sufficient guarantee for their personal safety. [...]

No promises made by, or on behalf of, the Polish Government can inspire confidence as long as the political police, whether Soviet or Polish Communist, remain a law to themselves. In March of last year the Polish Underground leaders who were given a formal safe conduct by General Ivanov were nevertheless arrested on arrival at his headquarters. After such examples of treachery the Polish exiles do not believe in any assurances which come from Warsaw." [44]

This scepticism was a view shared by thousands of Poles; good-faith was a commodity in short supply. Bernard Newman met one Pole who explained why he had not returned to Poland:

""You cannot picture it," said one man. "I was in a lumber camp in North Russia, almost in rags. You can guess the winter conditions. We were worked shockingly hard on a minimum of food. One day I said to a Russian officer who appeared friendly: "But why do you treat us like this? In your own interests you should feed us, so that we can work properly." He replied: "Why should we? We have tried out the system: at the present rate you will last for about five years. Then you will be used up, but there are plenty more where you come from!" Are you surprised to find that I don't want to go back to serve the remainder of my five years?"" [45]

Mieczyslaw Stelmaszynski was another Pole who had his reasons for not returning to Poland - he had nowhere to return to:

"Remember! That was our problem! To return to our country or to continue our wanderings. We received all sorts of horrific information from Poland - it was destroyed, burnt down. This played no small role. There was other information. That the Polish authorities of the time had completely subordinated themselves to the Soviets. Information about the arrests and deportations to the Gulag - in particular ,the soldiers of the Home Army. Wilno and Lwow had been taken away from us at Yalta. Many people had nowhere to return to; just like me. [...]

Some, paying no attention to anything, departed for Poland. Others preferred to wait, just in case the Third World War did break out, and yet others emigrated to the USA, Canada, Australia. The English were chasing the Poles out to Poland and our people considered those who went as traitors to the Fatherland! That's the way it was." [46]

Jean Carrer explained his reason for not returning:

"One of the biggest human tragedies was that these people who dreamed to return to Poland and join their families, when pressed to go back by the British Government were reluctant or refused to return. It is doubtful that anyone can describe this irony of fate, as it is impossible to describe hunger, love or hatred unless one is affected by such feelings. Next door to my quarters lived several officers. It was heartbreaking to see their internal fight. They all asked themselves the same questions. If they decided to stay in England, they would never see their beloved country and family; if they returned, they would be arrested or would not get any work. In both these cases instead of a help to their families they would become liabilities to them and would require their support in the form of parcels to a prison or another mouth to be fed. [...] They decided to wait. It seemed to others that compared to them I did not have any serious problems. My wife was with me and expecting a child soon. I did not have to ask myself the Shakespearian question: "to be or not to be" or, in any case, "to return to Poland or not to return." It was clear to me that I could not return and I did not have any intention of giving myself up to certain death after a successful escape just one year ago." [47]

Much of the propaganda against returning to Poland dwelt on the fact that it was the duty of 'patriotic' Poles not to return - they were expected to wait and fight against the Communist take-over in Poland. Couched in the terms of an idealistic crusade, the 'wait and see' gained credibility. Janusz Krajewski remained unconvinced, contending that he had not stayed in Britain from any idealistic motive - the idealists were, in fact, the ones who went back to Poland to help in reconstruction - and he freely admitted that he did not go back to Poland from fear.

The fear of returning was an overwhelming barrier that would prevent thousands from returning. Another Polish Soldier who did not go back explains:

"What was I to do? Grim news reached us from the homeland. Everyday newspapers and radio broadcast news of the terror in Poland, of the waves of arrests, court cases, sentences. Those who made their way from Poland added new snippets and career gossips magnified each small detail until they achieved the grandest proportions. Drop by drop the poison of fear which remained from Italy took hold. Nobody then was in a position to establish how much truth there was in all this and how much rumour. Everyone believed the worst. In our situation the rallying cry, "Return! The homeland is being rebuilt and needs your help" - far from reaching our hearts, missed its aim. I turned down then the chance of returning to Poland, as did thousands of others. I became an emigrant out of fear!" [49]

According to Nicholas Bethell it was not a fear of death that frightened the Poles from returning to Poland but rather it was the hopelessness of opposition to the Soviets and their acolytes. Indeed the soldiers who refused to return were, in general, the bravest troops in the Polish Forces who had been with the colours for the longest. During the war the Nazis had murdered millions yet there was hope - the Poles knew that sooner or later the Nazis would be gone and it was more a question of surviving in the meantime. The Soviet Army was a different proposition altogether. According to Bethell the West had "effectively abandoned Poland. There was no hope of Poland being 'liberated' from Stalinism." [50]

"The Economist" of August, 1946, took up the same theme:

"The Polish exiles are "non-repatriable" on the principle that a burnt child dreads the fire. This is not cowardice; the soldiers of Poland have demonstrated many times over that they do not fear death in battle. But they see no cause to face death without battle and without prospects of victory." [51]

Jerzy Lerski was a member of the Polish SOE who had parachuted into occupied Poland during the war to contact the underground and had made his way to the UK again. No one could accuse him of being a coward and yet he too did not return to Poland after the war. Although Lerski knew how to risk his life he had no intention of throwing it away. [52]

Many of the Poles took it upon themselves to tell the British authorities just why they were refusing to return to Poland and many wrote to Bevin directly at the Foreign Office. One artillery Colonel wrote:

"I trust the opportunity of returning to Poland will occur again. I will crawl back to Poland on all fours, when it is vacated by the NKVD, the Red Army and Messrs. BIERUT, ZYMIERSKI, RADKIEWICZ, ETC."

Another soldier wrote:

"I will accept anything that happens to me, but I don't want to fall for a second time into the hands of Communist liberators."

Szczepan Sadieski wrote to Bevin saying:

"We know, as well as you know, that there is neither freedom of the press or freedom of speech there. We know, from eyewitnesses returning from Poland, of the mass disappearance of people for no reason. You persuade us to return to that sort of Poland! No, Sir! A hundred times, no!" [53]

The War Office also had a good insight into the minds of the Polish troops. At the end of July, 1944, the Polish Base Censor noted these comments from one Sergeant:

"I will never go back to Poland if she is under Russian control because I don't want to be in the Red Russian Paradise. It is better to die than to go there. Really I don't know what I shall do after the War."

Another officer wrote:

"There is no return for us to the Soviet republic of Poland which seems to be the newest invention of our Allies. Those who know Russia from newspapers only or from propaganda don't realise that the life under the Soviet regime is not for civilised people." [54]

General Anders gave an interview to the former Mayor of New York and the then head of UNRRA, LaGuardia, in which he frankly outlined his views on why Poles were not returning to Poland:

LaGuardia: Why don't your soldiers want to return to Poland?

Anders: Poland is under Soviet occupation. The soldiers of the 2nd Corps know Russia very well since up to 60% of my men have been through the prisons and camps of the USSR.

LaGuardia: If the Polish Provisional Government gave the Allies a guarantee that any returning soldier would in no way be persecuted would many of them volunteer for return?

Anders: Today none of the troops believe in the pledges of either Poland or Russia. Not one commitment and not one pledge had been upheld by the Russians - not even Stalin's personal assurances to me. What then can Warsaw's guarantees be worth when they are so dependent on Moscow? [...]

LaGuardia: Your soldiers are, of course, good Poles and all of them, I am sure, would like to live in Poland rather than wandering around the world. To work in the reconstruction of the country and to change the regime it would be necessary to return to Poland and to influence the current of political life. Do I understand the situation correctly?

Anders: We are all waiting for the moment when we can return - but return to Poland and not a Soviet puppet. We will return when the Russian Army leaves Poland. In the Corps I have soldiers of the most varied faiths: Catholics (the majority), Uniates, Orthodox, Jews and Muslims. Nearly 75% of their number are workers and peasants. Everyone could, and can still, go back but at this present moment yet they all know that they would not return to a free country or a normal life. The majority would end up in prison camps or in Siberia. Any influence in political life or in economic life is as impossible in Poland as it is in Russia." [55]

Anders became known as the arch-anti Communist yet he apologised to no one for his opinions. He was asked by the Italian paper "Voce Adriatica" why his soldiers went around Italy pulling down all the "Long Live Stalin" posters, to which Anders replied: "To understand that you had to have been there...." [56]

As well as the pressure from within the military establishment from senior officers and from colleagues, there was the pressure from friends and family in Poland. Anderson H. Foster visited Poland in 1946 and asked some members of the soldiers' families for messages to take back with him regarding the return of their relatives. "What shall I say to your son?" he asked one mother; ""Tell him I want to see him." "You will do no such thing," snapped the daughter, "it would be madness for him to return and you know that mother."" [57] The war and the political situation afterwards split families and it was the troops with families in Poland that felt the misery of exile most acutely. As Mrowiec wrote:

"For years nostalgia had been gnawing at us and a million times on our distant path of war we had thought of our mothers, or wives and our children. In our dreams we visited our homes and asked ourselves if our dearest were alive or if they had anything to eat - we never received an answer: Anyone who doesn't understand this will never understand the most worthy impulse that inclined us to return." [58]

The political divide separated the families of even the most powerful in Poland. The Commander of the Polish Armed Forces in the East, Poland's Minister of Defence, Marshal Zymierski had, according to Kuropieska, two brothers who served in the West - Stanislaw who was in London and Jozef who was in Palestine with an armoured unit. [59]

There were, of course, families who said they wanted their relatives to come back to Poland from exile. Foster Anderson met the son of a colonel and asked his usual question of whether he should tell him to return to Poland. The son's first piece of advice was that his father should not get mixed up in émigré politics as it would permanently damage his chances of returning to Poland. As to the return the son's answer was:

"Yes. I cannot bear to think of him as an émigré exiled from Poland. That is no life for an old man. If he were young and without a family that would be another matter. He could build up his life abroad. But he is old and he is too Polish to do that."

Anderson asked the son if he worried about his father being arrested of imprisoned:

""I do not know anyone returning having been sent to Siberia."

"That does not answer my question."

Again silence. Then the youth burst out: "My mother wants him back. He may have got into his head that hopeless idea of Anders' that Polish officers must become crusaders and cut themselves off from their families so as not to be weakened in their resolve."

"Crusade for what?" I asked.

"The freedom of Poland."" [60]

Another soldier who received a letter from home was Edmund Thielmann who in March, 1947, got a letter from his mother asking him when he was coming home. He describes his reasoning for returning home:

"I can't put it off any longer. Its time to make a decision.... Am I to join the PRC and cut myself off from everything that has been important to me up to now and in the name of which the account of wrongs had been evened? No, I can't do that. It would mean renouncing my national identity....

- Colonel, I would like to report that I am returning to Poland!

- I wish you well - the commander of the regiment shook my hand and smiled sorrowfully... He had signed himself up for a course in tailoring. I felt sorry for the old soldier." [61]

Jan Podoski, who returned to Poland on a fact-finding mission for UNRRA with three tons of penicillin, was told by Cardinal Sapieha that although there would be bad times ahead, as many Poles as possible should return. This, notes Podoski, was not what his senior commanders wanted to hear and he was treated with scepticism and his popularity within his unit fell to zero. [62]

Karol Popiel was one of the Poles who agreed with Bevin that his patriotic duty was in Poland:

"The reader who is used to the émigré slogans may say that this was probably naive or an agreement to the Yalta accord. No. It is simply an admission of the unquestionable fact that the mainstream of national life runs along the Wisla and Odra. It is there that the nation examines the worth of its politicians. Above all the country wants to see in its leaders people who are ready to run risks alongside the nation." [63]

Tadeusz Czerkawski was one of the few front-line officers from the 2nd Corps who returned to Poland. He seems to have been swayed by the changes that had occurred in the country. He writes that the men of his artillery regiment were all cheered up when an AK Major informed them that it was unthinkable that Poland would revert back to its pre-war way of doing things. According to the Major the people had turned very Leftist. [64] Although, if left to its own devices, Poland might have turned to the political Left after the war - just as Britain had - there was little support for the type of government thrust upon Poland under Soviet auspices, hence few Polish troops returned home to support the 'revolution'. Most Polish soldiers were not concerned with the political polemics occurring around them. Tadeusz Kochanowicz writes that none of the arguments around him awoke any interest. His main fear was of spending the rest of his life as an exile in Britain and, as such, made the only decision possible - he returned to Poland. [65]

In the Autumn of 1945, the British began to move the question of repatriation at a faster pace and asked the members of the Polish Armed Forces to volunteer for return. According to Kuropieska, 37,497 elected to go to Poland in this 'plebiscite'. The areas of operations that the volunteers came from were:

United Kingdom 23,000

Italy/Middle East 14,000

Germany 400

Polish Air Force 57

Polish Navy 40

Or, expressed as percentages of the total force in that area, the numbers were:

United Kingdom 38.8%

Italy 10.8%

Middle East 6.0%

Germany 1.2% [66]

This represented a total of 17.2% of the total number of Poles serving under British command.

The War Office strongly denied that they had ever organised a 'plebiscite' among the Poles but, after a question from Vice Admiral Taylor in the Commons, the Government admitted the numbers who had volunteered for return. There were only slight variations from Kuropieska's figures:

United Kingdom 33.0%

BAOR [Germany] 1.0%

AFHQ [Italy] 14.0%

MEF [Middle East] 4.5%

From a total of 207,000 troops, there had been 37,060 volunteers for repatriation or 17.9% of the total. [67]

The figures for the Polish Navy and Air Force were even less encouraging. According to an October, 1945, FO report to Hankey, then working in the British Embassy in Warsaw, from 4,000 naval personnel, only 30 to 40 had offered to return. From a total of 17,000 Polish Air Force personnel, only 57 men had volunteered - 50 'other ranks' and 7 officers of which only one was a Flying Officer. [68]

The Polish Forces tried to breakdown the figures to make sense of them and to establish who it was who was volunteering. The "Soldiers Daily" from the 19th December, 1945, proudly announced that the soldiers who declared themselves for repatriation in the 2nd Corps were not the soldiers who had been at Tobruk and Monte Cassino. By December, 1945, there were 14,207 Poles in Cervinara Repatriation Centre awaiting return.

| CORPS TROOPS |

BASE TROOPS |

TOTAL |

| Officer - Other Ranks |

Officer - Other Ranks |

Officer - Other Ranks |

| 3 - 4,660 |

4 - 9,540 |

7 - 14,200 |

| |

|

Of whom the following declared prior to 8th May, 1945: |

| 3 - 2,600 |

4 - 2,900 |

7 - 5,500 |

Of these 5,500 'other ranks' 4,610 (83.81%) had formerly been in the German Army, 580 (10.54%) had been

recruited from France, Italy and other areas.

Of the men who had been with the Corps since the evacuation

from the USSR, only 310 (5.63%) volunteered to go back to Poland.

A different breakdown of the figures were those who had seen action and those who had not:

Infantry 870

Cavalry 65

Armour 20

Artillery 265

Sappers 100

Signals 35

Military Police 5

Supply/Transport 130

Stores 10

Engineers 40

Medical Services 160

| Frontline Troops |

Not In Action With Corps |

| 1,700 (30.90%) |

3,800 (69.09%) |

| Total : 5,500 |

[69]

General Anders commented on these figure with some pride. He felt that the men of his army - the "Anders Army" - had not let him down. In "An Army in Exile" he wrote:

"It is significant that out of the 112,000 in the II Polish Army Corps at the end of 1945, only seven officers and 14,200 men applied for repatriation, 8,700 being men who had joined after the end of hostilities. Of those who had come with us from Russia, and had been with the Corps throughout the campaign, only 310 applied for repatriation. Two things exerted a great influence on the men in deciding them not to go home. First, was the considerable number of soldiers who, after repatriation, fled from Poland and found their way through Czechoslovakia and Germany back to Italy, where they gave the men eyewitness accounts of events in the home country. Second was the significant wording of the letters sent back to Italy." [70]

There has yet to be a definitive study of the Polish Forces and how many soldiers returned to Poland from any particular unit, however, the War Diaries of the larger formations do give some indication of how the detachments were thinking. The diarist to Reconnaissance Platoon, 5 Battn, 2 Brigade, 3rd Carpathian Div. noted with pride that after Bevin's "Keynote" campaign, not one soldier volunteered for repatriation, [71] a fact also noted by 4 Company, 4 Battn, of the 2nd Brigade. [72] Bevin's words seemed to be having little effect among the front-line troops in Italy. This was not a universal phenomenon - the 3rd Battn of the Polish Parachute Brigade saw a marked increase in repatriation after "Keynote". The unit size was 40 officers and 414 men and the diary notes the number of troops who volunteered for repatriation:

| Officer |

Other Ranks |

| 24 January 1946 - 0/ |

15 |

| 3 April 1946 - 0/ |

74 |

| 6 May 1946 - 0/ |

18 |

| 16 July 1946 - 1 / |

0 |

| 5 August 1946 - 0/ |

8 |

| 19 August 1946 - 1 / |

6 |

| 16 September 1946 - 0/ |

1 |

| 12 October 1946 - 0/ |

21 |

| 18 October 1946 - 0/ |

6 |

| 24 March 1947 - 1 / |

10 |

| Total: Officers 3 / |

159 |

[73]

The biggest jump in the figures came in April, 1946, just two weeks after Bevin's note was handed out. The 7th Workshop Company of 7 Division, a reserve unit that only came into existence at the end of the war, did not see a corresponding rise in March, 1946. The biggest move to Poland came in August, 1945, as 137 men returned to Poland - this was the best part of the unit's establishment. The unit was quickly brought up to strength but in September a further 105 left and December saw another 13 go. By the start of 1946, most of the soldiers who were likely to go to Poland had already left so that by Bevin's March appeal only a further four volunteered. The next move to repatriation came in December, 1946, just prior to the creation of the Resettlement Corps. The unit had been brought to the UK in July, 1946, and the complement of the company was 10 Officers and 148 men - of this number nine officers and only 66 men joined the PRC. Six men went to Germany and three became PRC 'recalcitrants', the rest returned to Poland. [74] These results from a non-combatant unit were fairly typical in the Army. New units did not have the esprit de corps of others - when 7 Workshop Company disbanded, only 24 soldiers had been with the unit for over two years. The 14 Armoured Brigade, also formed at the end of the war, reported a serious drain on its manpower. By the end of August, 1945, there had been 335 declarations for return from among NCOs and 'other ranks' - this amounted to 9.6% of the Brigade; within this number, however, there were glaring differences across the board. 20% of the Signals Company returned to Poland, 32.8% of the Service Company returned and the Materials Park lost 43.5% of its troops. The report highlights the case of army cooks who seemed particularly prone to returning to Poland - 14 Service Company had no cooks left in its ranks. [75]

The 65th Pomeranian Infantry Battalion, formed in January, 1945, also showed that these new units were more likely to return than the more established ones. The unit was formed in January yet on the 27th July, 1945, one officer and 154 'other ranks' returned to Poland. The numbers were quickly made up so that when the unit was moved to the UK its strength stood at 817 men yet, even here, a further 310 soldiers returned to Poland rather than join the PRC. [76]

The opening of the PRC list seemed to give a certain impetus to the undecided about whether to return or not. No.1 Battery, 5 Wilenski Field Artillery Regiment had a total strength of 68 gunners. In April, 1946, seven returned to Poland from Italy just after Bevin's 'Keynote'. On the 16th September the unit was moved to the UK in preparation for joining the Resettlement Corps. The list for the PRC opened on the 13th January, 1947, and exactly a week before, 25 Poles volunteered to return. [77]

Some of the longer-standing military units did not show these returns en-masse but rather a steady trickle over the two years in question. The 3rd Heavy Machine Gun Company of 3 Battalion, 3rd Carpathian Division had an establishment of 166 men; the returns to Poland were:

18th December 1945 : 6

15th January 1946 : 6

18th February 1946 : 3

19th April 1946 : 1

8th October 1946 : 5

1st November 1946 : 11

14th November 1946 : 13

18th November 1946 : 7

26th November 1946 : 14

30th January 1947 : 1

12th February 1947 : 2

====

Total........................ 69

A further 14 stayed in Italy to go on to Canada and five stayed in Italy to marry Italians. Even in this unit,

although the returns were ongoing, the biggest rise in repatriation came in November, 1946, as 45 men decided

to leave at that point once the unit had been brought to the UK. [78]

These figures are largely confirmed by the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs in Warsaw who published the figures for the return to Poland from 1945 to 1949:

| | WINTER | SPRING | SUMMER |

AUTUMN |

| 1945 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

12,100 |

| 1946 |

22,500-- |

5,800-- |

3,100 -- |

7,000 |

| 1947 |

6,300 |

25,200 |

9,200 |

8,600 |

| 1948 |

3,000 |

1,600 |

500 in 2nd half of year |

| 1949 Around 1,000 in the whole year |

The end of 1945 and start of 1946 saw the first flurry of repatriation as those who were going to go went home

regardless of events in Poland. Then, even after Bevin's advice in the Spring of 1946, the rush died to a steady

flow until the Polish Armed Forces were brought to Britain. As the prospect of joining the PRC loomed ahead of

the Poles, so another mass move to repatriation began in the Spring of 1947 and the soldiers who returned after

that were those who became disillusioned with life in the UK. The total figures for return to Poland were:

| 1945 - 12,100 |

| 1946 - 38,400 |

| 1947 - 49,300 |

| 1948 - 5,100 |

| 1949 - 1,000 |

| Total : 105,900 |

[79]

As of the 1st November, 1947 the total strength of

the Polish Army and Navy in the West had been reduced by about a half. Its strength stood at 67,263.

TOTAL:

1/8/1945 : 216,379

+

Recruited after : 6,914

=======

223,293

minus

Repatriated to Poland : 101,056

Repatriated to other countries : 7,172

Emigrated to third countries : 14,218

Enlisted in the PRC : 30,886

===========

69,961

Minus Other Losses 2,698

==================

67,263

of which:

|

| :In Great Britain | : In Other Areas |

| Officers | 13,016 | 654 |

| Other RanksOfficers | 46,983 | 2,426 |

| Women's Army | 3,852 | 332 |

|

| 63,851 | 3,412 |

| Total......... 67,263 |

[80]

The other major body of Poles who were trying to

decide whether to go back to Poland or not was General Pruger-Ketling's 2nd Infantry Division that had spent

the war interned in Switzerland. After the collapse of the French Army in 1940, the Division that had been fighting

under French command had crossed the Swiss border rather than fall into German hands. In 1945, however, their

problem was the same as beset the rest of the Polish military - to return or not?

The Warsaw repatriation authorities took a great deal of interest in the fate of the 2nd Division with its 3,618 men. A report from the 7th November, 1945, found that 1,848 had expressed the desire to go the France to live - many in fact were Poles who had been living in France before 1939. 686 Poles were either on courses in Switzerland or would not be returning to Poland come what may, and some 1,084 would vote to return. Pruger-Ketling had the idea of settling his men as a body in the newly acquired areas of Silesia and, in particular, the town of Klodzko, formerly German Glatz. Indeed, to that end he established a Temporary Settlement Commission and found 486 men to join him. [81] As well as the soldiers, there were a further 1,700 Polish civilians in Switzerland who also had the same difficult decision to make. A report from Warsaw highlights the situation for these Poles:

"1/ The group of committed opponents to the new order in Poland are not numerous but are well organised and serve the former Government in London. They have at their disposal certain financial resources and have connections in the world of Swiss business. They publish a newspaper - Paszkwil [lampoon] which is presumably subscribed to in Germany and Italy. The group is recruited from amongst the intelligentsia and the pseudo-intelligentsia. Their impact is, however, limited. Their range of activity in this territory is small.

2/ The undecided group is partly being influenced by 'London' propaganda. They will decide to return when the repatriation is organised and when communications with their families are more secure (letters, etc.)

3/ The largest group is those who have decided to return. On the whole this element is very healthy and positive. 97% of the civilians arriving here from Germany before the end of the war, and 60% of the 2nd Infantry Division belong to this group.

4/ The old émigrés who in part look favourably on the New Poland have no intention of returning to Poland due to the nature of the economy and to private life." [82]

These 'Swiss' Poles at least had the option of returning to their homes - few came from Eastern Poland that was now part of the Soviet Union - but another group of Poles who had had their homes taken away from them were the 'Czech' Poles. After the First World War, the Czechs had overrun the Zaolzie area of Poland with its largely Polish population and, following the Munich agreement in 1938, the Poles reoccupied the area much to the delight of the locals. Poles from the towns of Cieszyn and Frysztat who were in the West were faced with the dilemma of returning to their homes and becoming Czech citizens or resettling in Poland. According to Kuropieska, this problem affected nearly 2,000 troops. The problems were compounded by the poor relations at the time between the Polish and Czech Governments [83] as each made territorial claim and counterclaim. The Warsaw Government did not help the issue by giving unclear advice to its charges. Polish Foreign Minister Modzelewski, during a visit to London in January, 1946, advised the Zaolzie Poles to put off making a decision about return until the negotiations between the two countries had reached some agreement. Sadly for the soldiers in question, these talks did not provide a solution and in April, 1946, the Polish ambassador in London could "still see no possibility of giving the people of Zaolzie any advice other than staying abroad and awaiting further developments." [84] The biggest problem for the Polish Government was that if the troops decided to settle in Poland - the 'recovered land' in the West was one possible area - then the soldiers' families would also follow, thus depolonising the area. [85] It was not until 1958 that the borders between Poland and Czechoslovakia were formally settled and today the Zaolzie Poles remain a sizeable national minority in the Czech Republic.

Another of the groups who found their future uncertain were the 'Volksdeutsche' - Poles who had been classed by the Germans, to a lesser or greater degree, as their own. When the Germans occupied Poland they compiled a list - the 'Volksliste' - of people who were German or Polish citizens of German decent.

According to a report from Major Gondowicz of Warsaw's Repatriation Mission in Germany to HQ BAOR in November, 1946, there were four classes on the Volksliste:

Class 1 - Full German. These people belonged to pre-war German associations were fully German and had 'Reichsdeutsche' identity cards. These people had no right of repatriation to Poland and had lost their right to citizenship and rehabilitation to Polish society.

Class 2 - 50% German. The Nazis issued blue identity papers to these people who had a "positive attitude" to Germany and the German occupation. These people had lost their citizenship but could reapply for it after a process of rehabilitation.

Class 3 - German by name, origin or ancestry and holding green identity papers. It was possible for this class to return to Poland and sign a declaration of 'Polishness' - no rehabilitation was needed.

Class 4 - The holders of yellow identity papers could best be described as 'Germanic' rather than German. These were the least trusted by the Nazis.

According to Gondowicz, a return to Poland depended on which class the Volksdeutsche belonged to. He went on: "It should be made clear that enlistment on the "Volksliste" could take place only on base [sic] of a voluntarily signed application." [86] This, as Gondowicz probably knew, was not strictly true. Names very often appeared on the Volksliste without the consent of the owner. Very often fear promoted people to sign and often, given the harsh terms of the Nazi occupation, the promise of better conditions were enough incentive for people to sign up. Franciszek Janikowski was a Pomeranian who had been conscripted to the German Army before joining the Polish 1st Armoured Division. His appearance on the Volksliste was typical:

"My father worked on the railways. He had no land and no fortune so he was afraid. When they took them away in 1942 and asked who doesn't want to be Germanised? Nobody answered. My father signed and, as he told me later, he thought: I have a son and he is going to go to war...." [87]

Ludwik Matuszek from Wielkopolska tells much the same story:

"What can I have against my father? That he was German? We lived in Wielkopolska, we were Polish citizens. The Germans came - father had to quickly become German. Nobody asked if we wanted to or didn't want to. People who live by borders never quite know to whom they belong. One day here, tomorrow there.... That we went to war, what about it? I was called up and I had to go. If I hadn't gone I would have been a deserter and we all know what happens to them." [88]

The propaganda from the 'London' Poles was also directed at these Volksdeutsche Poles to discourage them from returning to Poland. Pamphlets like "The Guide for a Returning Soldier - A Explanation Of The Provisional Government Of National Unity's Declaration About The Treatment Of Soldiers Of The Polish Armed Forces Returning To Poland" (a pamphlet that the Foreign office was quick to disclaim as being printed in London by civilians on a commercial basis so not liable to any action on their part [89]) were quick to point out that the Volksdeutsche - even of the class 3 and 4 - were seen in Warsaw as collaborators with the Nazis and their fate could only be imagined. As the warning in the pamphlet states:

"In other words every one of our soldiers who returns to Poland and had the misfortune to belong to the 3rd and 4th group Volksdeutsche through no fault of his own will be at the mercy of the first troublemaker or person with whom he has an argument and reports him to the secret police that his behaviour during the German occupation was not "compatible with Polish nationality". It is difficult to defend oneself against such an ambiguous and general accusation. What it will result in is the accused being locked up in a concentration camp...." [90]

How Warsaw actually felt about the Volksdeutsche is dealt with later, but the fear of reprisal that was produced by such propaganda could, potentially, have dried up the repatriation of the thousands of men who had previously served in the Wehrmacht. However, the situation produced a major anomaly as the Poles who were the most anxious to return to Poland were these very Volksdeutsche. As already stated, the units that produced the highest rates of return were the units that had been formed toward the end of the war and were manned, predominantly, from the nearly 29,000 men who had been in the German Army.

The propaganda that emanated from both sides of the Polish political divide after the war did much to formulate attitudes to return among the soldiers, sailors and airmen concerned. Many did not return to Poland - many did. Few of those who went back did not suffer, one way or another, at the hands of a regime that disowned them. Dzennet Skibniewska, a Polish Tartar who served in Italy with the Polish Women's Auxiliary Corps, puts forward a common view that the Poles did not deserve the treatment that they received in Poland:

"Who today from the 'authorities' of the former People's Republic of Poland remembers those years just after the war and the return of those who had lived through its nightmare? For years they had fought for Poland. They dreamed of peaceful work; they were homesick for the land they had not tended for so many years; for their nearest and dearest. When they returned they were met by all manner of trouble. Can those who lie in the Monte Cassino cemetery rest in peace until someone finally realises the tragedy of those days? Personally, I think they should apologise to us. It's the least they can do. To say - we're sorry. One little word - sorry!" [91]

As a postscript to this, Aleksander Kwasniewski, the man who finally closed the Polish United Worker's Party, stood in the Polish Parliament on the 9th November, 1993 and announced:

"I also want to say today - although perhaps it is not up to me to say this - to all those, and some of them are here in this chamber, who experienced wrongs and foulness from the authorities and the system before 1989: We are sorry. [Applause]" [92]