Although Inertia is no longer a part of the AP Physics B course, we students are still responsible for the topic of conservation of angular momentum.

Although it may sound complicated, the conservation of Angular Momentum can be sumed up into one simple principle:

The total angular momentum of a system remains constant (is conserved) if the net external torque acting on the system is zero.

Simple, right? Well I suppose the exact wording of the Physics text book can make it sound more confusing than it is. Remember back when we analyzed momentum and how it never changes in a system in an earlier course unit? Well angular momentum works the same way. To put it simply, when you increase the distance or radius of a system the speed decreases and when the radius decreases the speed increases, provided that the mass remains the same. This principle yields the formula for conservation of angular momentum:

When you think about it, this makes sense. Have you ever done spins while skating or watched someone else? To gain speed in a turn, you may have seen someone whip their arms in close to them, to gain momentum. If you think of the person's turn as being a circle, when they whip their arms in, the radius becomes smaller and they go faster. If that same person extends their arms, the radius increases again and you'll notice that, so long as they don't give themselves an extra boost or force, the speed will decrease. The same is true if you spin a ball on a string and without appling or removing any force, decrease or increase the radius.

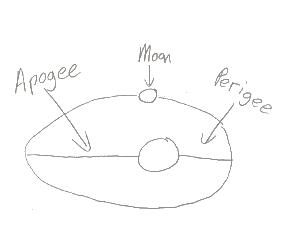

In AP Physics, this formula and principle are most commonly used to solve problems involving elliptical orbits in space. The following diagram illustrates some important terms to understand when talking about elliptical orbits.

This is a picture of a planet and a moon orbiting it in an elliptical fashion. You will notice that certain places in the orbit are referred to with specific terms. The term "Apogee" refers to the place in the orbital path that is farthest away from the planet. The term "Perigee" refers to the place in the orbital path where the satellite or moon is closest to the planet. These terms might show up again in a problem, so you should be familiar with them.

When dealing with an elliptical orbit style problem, always keep in mind the conservation of angular momentum. As the net external torque in an elliptical orbit is zero, the formula m(v1)(r1) = m(v2)(r2) works for all cases. Thus when the moon is in the Apogee part of its orbit, the speed is always less than when it is in the Perigee part of the orbit. At any given instant in the orbit, the angular momentum is always equal to the angular momentum at any other part of the orbit. Total angular momentum is always conserved in this type of problem. Knowing this is the first step to solving problems dealing with the conservation of angular momentum. The second step is to have some question values, so head on over to the sample questions to see how exactly you would work out a problem dealing with angular momentum. Then you can try some problems yourself by following the second link.

Problems For You To Try

Problems For You To Try