Down in the dumps:

In WNY, hazardous waste problems lie

just beneath the surface

If you drove past True Bethel Baptist Church in the early 2000s, you might have seen something that God did not intend—a man wearing a gas mask and ministerial robes, pulling weeds out of the lot across the street. The man would have been Reverend Darius G. Pridgen, senior pastor at True Bethel. The lot would have been 858 East Ferry, an unfenced, abandoned area that used to house a lead smelter.

In 1998, the City of Buffalo found the soil at the site to be significantly contaminated. Reverend Pridgen’s gardening was the least of his efforts to clean up the hazardous wasteland at 858 East Ferry. His vigilance on the issue was a major factor in its eventual resolution, a victory that is a glimmer of hope for the uncomfortably large number of contaminated sites in Erie and Niagara Counties.

“The Reverend wasn’t going to take this contamination issue sitting down,” recalls Dr. Joseph Gardella, professor of chemistry at the University at Buffalo and a prominent local environmental activist. “There was no identification that this was a hazardous lot. He was fighting City Hall just to get a fence up to stop kids from playing on it.” After an extensive investigation, the Department of Environmental Conservation reported that the problem extended far beyond the East Ferry lot (according to DEC documents, the volume of contaminated soil increased from 3,575 to 87,200 cubic yards). And like Pridgen’s congregation, which has blossomed to more than 3,500 members, a campaign for a fence grew into a community-wide force that couldn’t be ignored.

After five years of effort from community organizations, government officials, Dr. Gardella, the DEC, and many others, the neighborhood got more than a barrier; a full-fledged clean-up project began in October 2006. It will likely be completed by the time this article goes to print.

As of February 2008, there are sixty-three Erie County locations on the DEC’s Registry of Inactive Hazardous Waste Disposal Sites. Of these, twenty-three are “Class 2” sites, which means they present a potential threat to public health and/or the environment. That’s the fourth-highest number in the state; Nassau County’s the winner, with seventy Class 2 sites. Niagara County has fifty-three sites on the Registry, fourteen of which are Class 2. For Western New Yorkers who love their communities, these statistics make the words of Britney Spears seem appropriate: “I’m addicted to you / Don’t you know that you’re toxic?”

When looking at solutions to this seemingly insurmountable multitude of problems, 858 East Ferry should be a model. “This is how you win,” Gardella declares. “The community is completely engaged.” And while the work of Reverend Pridgen and the East Ferry community has been the exception to the rule when it comes to battling hazardous waste in our neighborhoods, it’s a story Western New Yorkers have heard before.

It’s only appropriate that it reaches its triumphant climax in 2008. This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of Love Canal, the Niagara Falls community that was built on an industrial dump. Lois Gibbs, the housewife-turned-activist who led the Love Canal protests all the way to the Carter White House, provided our area with a context for public participation that continues to echo in places like 858 East Ferry.

“A lot of people believe that if you have the science on your side, if you have the facts on your side, if you can prove that something’s wrong, that’s enough,” advises Gibbs, who is the executive director of the organization she founded after Love Canal, the Center for Health, Environment & Justice. “Just because you’re sick, or the water is polluted, or the fish are dying, it doesn’t make the government or the corporations that you’re fighting step up to the plate and rectify the situation. It’s really hard for people to believe that. We get so bought into what we learned in high school—that all you need to do is approach government when there is a wrong, and then they will do the right thing. And at the same time, when people do this, they get pointed at. They’re told that they’re creating hysteria when there’s no need to. But the fact of the matter is, that’s the only way change has ever happened in this country, whether you’re talking about women’s right to vote or civil rights or Love Canal.”

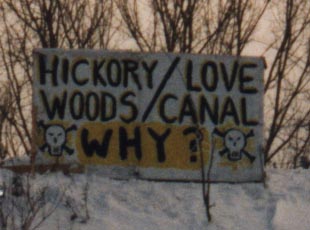

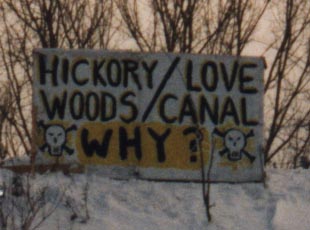

The formula that Gibbs proposes isn’t an easy one—convince a large group of individuals to take on monolithic entities and expose themselves to public scrutiny, with no promise of success. It happens in movies all the time, like the 1987 film The Monster Squad, when a group of middle-school losers have to keep Dracula and his rag-tag team of famous monsters from taking over the world. But there are two examples in our backyard that life ain’t like the silver screen: Hickory Woods and Lewiston-Porter.

On January 8, the Buffalo Common Council unanimously approved a $7.2 million settlement for the residents of Hickory Woods, a South Buffalo housing project built on contaminated soil, courtesy of the area’s previous industrial owners, which include the Hanna Furnace Corporation, Donner-Hanna Coke Corporation, National Steel Corporation, and LTV Steel Company, Inc. Unlike the Love Canal settlement, which Gibbs describes as, “here is X amount of dollars for your house, and you go wherever you want to go,” there is a limited amount of money to go around. If an individual settlement isn’t enough to pay off the mortgage and move out, you’re essentially stuck. And as of this writing, no clean-up project is on the horizon.

Why did all the community activism at Hickory Woods have such underwhelming results? According to Gardella, the problem lay at the doorstep of 65 Niagara Square. “It was Anthony Masiello who promised the residents that he would fix the problem. Then he went back to City Hall, and was surrounded by people who had no intention of fixing the problem. They were only interested in getting out of it with the minimum input. They used the standard tactics—divide and conquer, try to split up the neighborhood, play people against each other, wait ’em out, hope they disappear. [Hickory Woods] is a case study on why these are the wrong people to put in charge.”

Regardless of who’s at fault, Hickory Woods was in need of a Love Canal-esque evacuation and never got it. People are still populating an area that Gibbs calls “a place where people are never going to be able to live safely.” At this point, even the most miraculous solution will be bittersweet.

While Hickory Woods is a catastrophe, at least it’s easy to drum up a scapegoat. In the Niagara County community of Lewiston-Porter, there are so many grey areas, it’s impossible to boil it down with “good guy vs. bad guy” rhetoric. Even so, let’s try to put together a Cliffs Notes version of the situation:

• Chemical Waste Management (CWM) operates a hazardous waste landfill in the area, which it hopes to expand in the coming years. It’s the only landfill of its kind in New York State.

• The Niagara Falls Storage Site (NFSS), where 2,000 curies of high-level radium is stored, is also in the area. It is maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and is a temporary storage solution. There are no official plans for a permanent solution.

• The NFSS sits on the southern portion of the former Lake Ontario Ordinance Works (LOOW) production area, which was used by the Department of Defense to manufacture TNT during World War II and store radioactive materials while the atomic bomb was being developed.

• As LOOW operations were scaled back, much of the land was sold off. Current inhabitants on former LOOW land include the Lewiston-Porter School District.

Even in neat, bulleted form, a solution to all the problems in Lewiston-Porter looks daunting. And the entities that seem easy to blame (CWM, the USACE), aren’t necessarily the real villains. Consider the CWM situation. It seems obvious that its hazardous waste landfill should never be expanded. But when hazardous waste sites like the one at 858 East Ferry get cleaned up, that contaminated soil needs somewhere to go.

“It’s always nice and easy to say, ‘No more garbage. No more landfills of any kind,’” argues Lori Caso, community relations manager at CWM. “These are necessary.” Caso references the recently opened Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority hub near the Factory Outlet Mall in the town of Niagara, built on land that used to be a brownfield. Almost eight thousand tons of chromium-contaminated soil were taken from the site and packed into the CWM landfill. “This soil was brought here to us,” Caso explains. “These are state-of-the-art landfills; they do not leak. Now they have a brand-new, state-of-the-art bus terminal. And we have a brownfield that turned into something that is actually now generating money. It’s a brownfield success story.”

Lois Gibbs agrees with Caso’s point that shipments of hazardous waste have to go somewhere. But should it be shipped at all? “The vast majority of waste, even if it has to be treated, can be treated in a flow loop system, not going into the air or into the water, and it should be done on-site,” Gibbs says. “Our technology has come a long way. There actually is a process for ninety percent of the hazardous waste that is being generated, but it has to be done in small quantities and at the facility where it’s being generated. Once you mix it all up, put it in a tanker truck, and take it to Lewiston-Porter or wherever you’re going with it, you’ve now created this nightmare. There’s nothing you can do with it.”

Similarly, solving the NFSS scenario seems easy; just ship the radium to some uninhabited area and store it there. But as Gardella points out, that’s easier said than done. “That’s a very complicated problem,” the professor explains. “It’s not nuclear waste. It’s high-level radioactive material. The Army Corps has created a temporary storage solution, and how long is that going to be? Nobody knows. What do you do to store high-level radioactive material, and you don’t have someplace else to put it? Do you ship it down to New Mexico? They don’t want it there. There’s no clear path.”

Unfortunately, words like “nightmare” and “no clear path” tend to encapsulate the state of things in Lewiston-Porter, where activists and corporations continue to clash, and both sides present arguments that are tough to poke holes in. And with the school district in the middle of it all, these fights are intensely emotional. Unlike 858 East Ferry, where the sheer will of the community and a few well-timed government grants made all the difference, there are way too many cooks in the Lewiston-Porter kitchen, and the soup doesn’t taste so good.

Leave it to Lois Gibbs to lend some hope to the whole fiasco. “There has been a real change in industry in general since Love Canal, where they are really working hard to reduce the amount of hazardous waste they take off-site,” she observes. “Industry is really looking at how they can reduce it, and I think with some encouragement from government, it could go a long way. If corporations deal with it like homeowners—they put their trash out on Friday and their recycling out on Saturday—we wouldn’t have this, ‘it’s gotta go somewhere.’”

Gibbs’ optimism is certainly refreshing, but it’s tough to share in it. Are corporations really going to come to our rescue? Will a legion of rich white knights make landfills obsolete and prevent future horrors like Love Canal, Hickory Woods, and 858 East Ferry? I wouldn’t hold my breath. Unless I lived near a Class 2 site, that is.

Appeared in the April 2008 issue of Buffalo Spree.