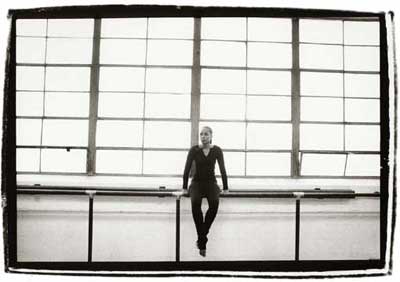

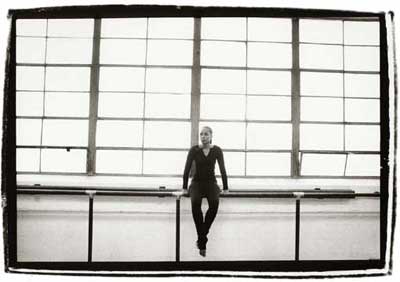

I was lost, walking through the bowels of Buffalo State College’s Rockwell Hall, having no idea where to go and what to expect from the performance that I was about to witness. Being far from a connoisseur of the art of dance, I was on my way to sit in on a rehearsal of Janet Reed’s critically lauded dance collective, simply called Janet Reed and Dancers. Immediately after entering the white-walled studio, Reed gleefully sat me in the corner by the stereo, apologizing in advance for what was to ensue, a sensory assault that (judging by my frightened, daft, puppy-like countenance) she knew I wasn’t expecting.

“So sorry, but you’ve gotta sit near the speakers,” Reed said. “I’d brace myself; we like to rock in surround sound.”

The rehearsal that I was lucky enough to witness that night was a downright spectacle of visual and aural artistry. Reed’s choreography breathes with organic spirituality, tapping into a reservoir of human instincts that is mostly lost in a suffocating world of fast food, 24 hour news tickers and Alan Jackson ballads. It’s a style all to itself, a combination of African and Caribbean stylings with a dash of regimental ballet strictness – a whirlwind of emotional, humanistic modern experimentation. Even when citing influences, Reed’s not fond of limiting her work to the confines of a label or genre title.

“So far Contemporary African has been the closest description – the jury is still out on that too,” Reed says. “What bothers me about labels is whether someone will even give something a chance because of a label. I’m already full of labels: African American, woman, mother, teacher, lover, friend, etc. Labels can open doors, but they also may give permission to not pay attention.”

Reed’s vast knowledge on the subject and her long list of influences is no accident. Her passion for dance was born when, at age three, Reed saw a ballerina in a store window and pointed it out to her mother, who enrolled her in a dance school. After getting the standard ballet, tap, and jazz training, Reed’s creative juices began to push her away from the mainstream.

“As I got older my interests changed. I wanted a different type of expression. That led me to teachers who taught blends of modern dance with African and jazz in college (at SUNY Brockport). I became very adept at Traditional Ghanian Dance, a form that gave me confidence and later influenced the work I do today.”

Reed then went on to gain further experience teaching and performing in Seattle, WA, before returning to Buffalo to be the Artistic Director of the Buffalo Inner City Ballet, and an Assistant Professor of Dance at Buffalo State College.

“Having the desire to choreograph my own works, I began to use my work with other dancers, choreographing small pieces with children, adults and anyone I had access to. Through teaching I developed my [choreography] skills further, through trial and error. Time, patience and persistence allowed me to find my own voice in my work.”

This dedication to her craft is more than evident when it is performed, each dancer an integral part of a living tapestry that ebbs and flows with Mother Nature’s fluidity. Like the beauty of a John Coltrane sax solo, Reed’s works invoke strong moods and powerful emotions, without uttering a single word. “Passages,” for example, is a Reed piece that tells the story of the Griots, who were African storytellers that embodied the spirit of oral tradition, documenting the culture of their tribe and passing their knowledge on from generation to generation. “I Woman I” is an award-winning Reed work, a four-part tribute to the African woman. Inspired by artist Paul Goodnight’s painting “The Marketplace,” the piece depicts three women who are fighters, workers, nurturers and friends. Reed’s knack for incorporating characters and storylines in her work makes her not only a brilliant choreographer, but also a top-notch storyteller.

Not having a dancing background and knowing next to nothing on the subject, Reed showed me how dance is totally unique in the way it conveys human feeling, the stark physicality of it, the thought and care put into each gesture and nuance.

“The body, mind and spirit must connect on some level throughout physical exertion. I do a movement, but it could feel different each time. If I took a picture or painted, those things are held still for eternity–movement work can be different every time.”

An indispensable component of her pieces is the music, which is more than just a backdrop for the dancers. When coupled with the movements of Reed’s dancers, notes and harmonies are accentuated, simple beats become syncopated, rhythms are turned upside down. Her compositions build on the music, weaving in and out of its structures, breathing new life into it, making what was once only audible burst with color, becoming visible to the naked eye.

“I love the new age/world music blends, the hidden spiritual aspects of music like Gabriel Roth and the Mirrors.” Reed says. “I can really get off on a funky percussive rhythm and an unusual melody. And sometimes the rhythm is all I need to go outside myself and just be. I don’t want to have to think about it too much, I’d rather feel it.”

At the rehearsal, Reed more than fulfilled her promise to rock, running through pieces that showcase a huge range of musical tastes that have one thing in common – they inspire you to move, whether it’s tapping your foot or shakin’ your ass. From Steve Reich to Mickey Hart, Afro-pop and vocal percussion to electronica and house beats, Reed’s obvious passion for music is at the forefront. Her love for the rhythm is at the center of her work, which has a constant pulse to it, feeding off of one of our most untainted human instincts–to clear our heads, and let the music take us away.

Appeared in Issue Two, 2002, of Traffic East.