When asked about the cavalcade of praise and hyperbolic declarations surrounding his new record Lifted Or The Story Is In The Soil Keep Your Ear To The Ground, 22-year-old songwriting alchemist Conor Oberst couldn't possibly be more humble.

"It's no different than any other record that's ever been praised," Oberst says. "I don't think it's really going to matter a few years from now."

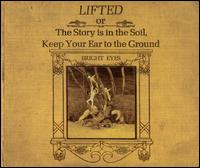

Lifted is the latest epic offering from his band Bright Eyes, a band consisting of Oberst and a revolving door of musical guests who drop by to put their mark on his profound creative visions. Regardless of what you're likely to hear from the mastermind himself, the album matters, and not only because of the crackling lo-fi guitars, dramatic strings and hook-filled heads. Rather, Lifted is truly significant due to its pure, unadulterated humanity. Oberst's lyrics bruise and bleed, confuse and inspire, give listeners chills and make stomachs turn.

Take, for example, a line from the darkened world of the song "Lover I Don't Have To Love," where Oberst muses, "You write such pretty words/But life's no story book/Love's an excuse to get hurt/And to hurt."

One of the themes of the record is the use of music as a means to communicate with the rest of the world," Oberst reflects. "I want that aspect of humanity to come across as much as possible. I think that's where we have the best chance of understanding ourselves, through music and art."

The songs from the Omaha, Neb., native are largely bleak, depressing affairs, but not in a quiet, Nick Drake sort of way. They're a group of unfettered, unpolished life preservers tossed to anyone drowning in like-minded sadness or frustration. Because Oberst throws the shadowy corners of his mind onto tape with scant self-editing, anyone who has felt lonely, broken-hearted or worthless can relate to the music on a very primal, emotional level. It's music for and concerning the downtrodden, and it's not meant to be uplifting.

Listing his father and older brother (who are also musicians) as defining influences, Oberst released his first tape at age 13 he hasn't looked back since. Without much prompting, the mild-mannered Nebraskan positively gushes about music.

"I'm trying to think of a moment when I realized I wanted to be a musician," he reflects. "It has just always been a part of me, a part of my family. Music has been so necessary in my life."

For an artist whose work is steeped to the neck in woe, Oberst never points fingers, unless they're at himself or the cruel and indifferent fates of the universe. By all counts, he's not your average 22-year-old. A memo to those trying to fit him in a neat little box because of his age it's not bloody likely.

"My youth has impacted the way people have perceived the music," he says, analytically. "For a long time, anything people wrote was 'This kid's really gonna be something after he grows up.' It's just like high school bullshit, constantly trying to validate your right to feel something based on your age. It's like I wasn't allowed to express true remorse for anything, or true sorrow for anything, because I'm too young to deserve those emotions. People are foolish if they want to paint all young people in a two-dimensional light, where there's no depth to them or their ability to think."

"My youth has impacted the way people have perceived the music," he says, analytically. "For a long time, anything people wrote was 'This kid's really gonna be something after he grows up.' It's just like high school bullshit, constantly trying to validate your right to feel something based on your age. It's like I wasn't allowed to express true remorse for anything, or true sorrow for anything, because I'm too young to deserve those emotions. People are foolish if they want to paint all young people in a two-dimensional light, where there's no depth to them or their ability to think."

Clearly, there are several dimensions co-existing in Oberst's work, with nary a sliver of trite my-parents-don't-understand-me brooding.

Lifted begins in traditionally clever Bright Eyes fashion, from the fly-on-the-wall perspective of a couple getting in their car, then driving and talking. A tape in the car cassette deck starts to hiss, then segues into the first song, "The Big Picture." The concept is simple a down-home, tender desire to connect with the human race, one commonly felt by past artists whose styles have had an obvious impact on Oberst Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, Joni Mitchell. It's quite clear Oberst's passion for his work is on par with these legends. In fact, it's actually quite hard to overstate the realistic beauty of a Bright Eyes record.

"The most good comes out of expressing yourself, not from striving for perfection or necessarily pleasing everybody," offers the soft-spoken Oberst.

While a consistent mood permeates most of Lifted, Oberst and pals mix things up musically, giving each song a new and classy twist.

"The challenge was to decorate them and give them their own identity," explains the fair-headed 20-something.

Oberst and his trusty production team of Mike Mogis and Andy Lemaster triumphantly reach this goal, recording potentially drippy string arrangements in a style combining the elements of basement-tape demos and bombastic Hollywood film scores. "Lover I Don't Have To Love" features a slithering, downcast Wurlitzer groove, while "False Advertising" is a raucous waltz with a Double Fantasy-style melody. "Waste Of Paint" channels the most brilliant aspects of stripped-down, mid-'60s Dylan.

The album is the most musically ambitious thing Bright Eyes has produced to date, taking all of the elements and influences from rock 'n roll and folk canons going for broke. More impressive is the cohesiveness of the record not for a second does a single note sound out of place.

"We filled up a lot more tracks on this record, but we were still after an organic sound," Oberst explains. "We wanted it to sound like a 16-piece band playing in a room."

Organic it is, but not just in a musical sense. It's organic in the thought processes and personal feelings inherent in Bright Eyes' songs, in Oberst's grandiose commentary about individuals and their place in the universe, in the rhetorical whys and hows that have stumped mankind since it crawled out of the primordial ooze. If Oberst is an existentialist, he's certainly not an optimistic one.

When asked about the blatant cynicism of his work, he replies in more of his patented, almost aggravating candor.

"I try to be as optimistic as I can in my daily life," he begins. "I try to be positive about what's going on, but that's just for the sake of the people I'm spending time with. You don't want to always be a drag. When I really sit down and think about stuff, I still feel pretty meaningless. I mean, the whole Earth is a fuckin' drop in the bucket really. And our time is so much less than a second, if you look at the way everything is set up."

Most people spend their entire lives trying to ignore this celestial downer of an idea, but Oberst opens the wound and adds a healthy dose of sodium on "Waste Of Paint," tackling the troubling question of our purpose in life and whittling it down to this in the end, nothing we could possibly do will matter. Nobody likes to feel meaningless, but Oberst doesn't back down for a second, spouting the lines with unbridled emotion "I hide behind these books I read/While scribbling down my poetry/Like art could save a wretch like me/Some ideal ideology/That no one could hope to achieve/And I'm never real, it's just a sketch of me/And everything I've made is trite and cheap/And a waste of paint, of tape, of time."

Listening to Lifted, all of the media machine's diarrhea is put promptly in its place. Taking its cue from the brasher, more politically charged world of Oberst's acclaimed side project Desaparecidos and its album, Read Music/Speak Spanish, Lifted tackles the American propaganda behemoth with its dusty boots planted firmly in the soil. While Oberst doesn't think the points of "Let's Not Shit Ourselves" will be discussed on Capitol Hill anytime soon, he still has faith in the power of artistic expression.

"Music in the '60s and '70s changed America," he says boldly, without sarcasm. "But everything is so much harder now. With all the advances in communications, I think we're being lied to on a daily basis."

In a ridiculously turbulent world, which Oberst describes as "everybody saying everything at the same time," the record eliminates everything extraneous to our inner thoughts and fears, ignoring the tidal waves of propaganda thrown in our faces every minute. It is, in the end, a guy with a guitar and a microphone telling the truth. It shouldn't feel so refreshing, but as Oberst says himself, people are being lied to everyday.

Bright Eyes records, meanwhile, seem to fulfill the promise of something real, even discussing how insecure and vulnerable being truthful can leave people. The sentiment is covered in"False Advertising," in which the first line is repeated three times before the band kicks in. An intentional mistake in the middle of the song leads to a musical train wreck. Somebody yells, "Sorry," and Oberst replies, "It's OK" counting off the waltz and ripping into the song's rollicking apex. Perhaps Glen Ballard would see this as a flawed recording, but as examples of humanity's imperfections, they're stunning.

When asked to describe the record in one word, Oberst calls it "long," following it with half a chuckle. For 73 minutes and 10 seconds, Bright Eyes wrestles with the mysteries of humanity, succeeding long enough for all of us to take a long, hard glimpse at our flawed reflections and try to make sense of the stranger staring back at us. Simply put, Lifted matters.

Appeared in the October 2002 issue of Rockpile.