The Battle of Oakland

December 3, 1862

Cavalry clash on the Memphis-Grenada Railroad

The

skirmish at Oakland played a key role in the railroad campaign because it

prevented a Union flanking of Pemberton’s forces in their Retreat from Abbeville. While the Confederates were in Abbeville,

Grant began pressing south toward their position. He then ordered Federal troops under General C. C. Washburn and

General Alvin Hovey to cross the Mississippi River at Helena, Arkansas and move

in the direction of Grenada. They

crossed and moved to the Panola area, which is about 25 miles west of

Abbeville, and 40 miles south. They

planned to enter Oakland, which is 12-15 miles due west of Coffeeville and 10

miles north of Grenada. By moving from

Oakland to Coffeeville they could have effectively cut off the Confederate

Retreat From Abbeville – having a Union force under Washburn to the south and

Grant to the north, with the Confederates trapped in between. This

Union flanking was the reason the Confederates began their Retreat from

Abbeville – they could not defend themselves in the swamps around Abbeville, so

they rushed to reach the safety of Grenada and Pemberton on the bluffs of the

Yalobusha River.

With

Washburn and Hovey moving near Oakland, CSA Col. Griffith made a cavalry attack

to stop the Union flanking, and was successful. Washburn soon learned of the heavy Confederate build up in

Coffeeville and did not pursue this plan after the encounter with

Griffith. In fact, following the

cavalry skirmish, Washburn retired from the immediate area now fearing that his

troops would be flanked.

General

Washburn:

“Concluding

that they (Confederates in Abbeville) would all fall back on Coffeeville, and

being satisfied that more or less force from Price's army was at Coffeeville, I

deemed it highly imprudent to proceed farther, as my whole force of infantry

and cavalry did not exceed 2,500 men. I bivouacked for the night on the public

square at Oakland.”

Colonel

Dickey, Grant’s chief of cavalry, was aware that Washburn had plans to move

from Oakland to Coffeeville, but was not aware of the cavalry skirmish with

Griffith. Dickey had wanted to press

the Confederate rear guard one more day from Water Valley in order to

rendezvous with Washburn, thinking it would be a morale boost to his men. For some odd reason, none of the Federal

commanders seemed to comprehend or expect such a large Confederate force in

Coffeeville that was growing stronger by the hour as more and more units

funneled into town on the way to Grenada.

The

significance of the Oakland skirmish is that it effectively prevented further

Union movement south of the Confederate rear guard, and allowed Pemberton’s men

to re-enforce Grenada. There most

likely would have still been a Battle of Coffeeville, with Washburn and Hovey

to the west and Dickey to the north.

The battle would have been much larger and fought in a broader area. It would have been a sizeable engagement,

and not a surprise ambush that led to a battle, as it eventually did

happen. And with all of the available

CSA forces in the area the Federals would have met a more overwhelming force,

since most of the Rebel troops were held in reserve during the Coffeeville

fight. If attacked by Union forces on

two sides, several thousand more Confederates would have been brought into

play.

Interestingly,

Union General Alvin Hovey’s great grandson, Dave Hovey, lives in Coffeeville

today.

***

A Civil War Experience in Oakland

Oakland Citizen Describes the War

An article written by Miss Emma G. Moore,

Oakland, Miss., a descendant of one of the oldest and most prominent families

in this county, for the "Progressive Farmer Magazine" issue of

November, 1936:

"It was a

cool pleasant day in early December. To be exact, it was Thursday - the 3rd day

of the month, in 1862. News had been received that the Yankees were on their

way south from Memphis, making their way to Vicksburg via Grenada, Miss.

Oakland was a small town eighty miles south of Memphis, and twenty miles north

of Grenada, with the Miss. and Tenn. railroad, now the L. C. railroad, running

north and south through the center of the town. That morning my father had

hurried to his plantation, two miles south of town, and with his manager

(overseer he was then called) and a few trusted Negroes, was rapidly rolling

cotton bales from the gin, and hiding them in ravines and gullies, covering

them with leaves and brush, and making preparation for the passing of the

Yankees, for their route would be right through his plantation. Our house was

about one half mile east of the railroad, a large one-story house with rooms 18

x 18 and 20 x 20 and halls correspondingly long and wide, with a long gallery

in front extending the front of the house, with spacious grounds in back and

front. The house was in the center of a long lawn, each end of which was

planted in flowers, shrubs and ornamental trees.

Such a

beautiful front yard, the pride of my father's heart - also of Jimmie Garvin's,

the Scotch gardener; and you never saw Jimmie without his wheelbarrow and

spade, for he kept this yard in excellent condition. In front of the house grew

eight large silver poplar trees, giving such beautiful shade, and also a name

to the home, for it was called "The Poplars". Back of the house was a

large smokehouse built of logs; also the kitchen was a large log room, with

immense brick hearth and fireplace, in which hung a crane with numerous and

different sized pots. A brick walk led from the dining room to this kitchen,

over which Chaney, the fat cook, had for many years reigned supreme. It was

nearly noon, and my mother had given orders to Chaney to have the noon meal

ready and waiting for the three older school children, and their Connecticut

School teacher, on their arrival from school. So Chaney had called Sally Ann,

whose duty it was to transport the meals from the kitchen to the dining room

(when she wasn't attending the baby). At the door of the dining room, Maria

Thomas, dining room maid, would receive the dishes and place them in proper

order on the table. She would then take her place, standing back of my mother's

chair. In the summer she usually wielded a long brush made from a peafowl's

tail, to scare away any misguided fly that might have found his way into the

dining room. These peafowl brushes were really beautiful, with their lovely

chameleon change of bright color, and long handles finished in white or colored

kid, matching the feathers. They were made in New York or some northern city,

but nearly every southern family used them.

After attending to this midday duty, Sally

Ann wended her way back beside the crib, and found the baby had not yet

awakened from her morning nap. My mother, seated in her rocker by the fire, was

putting the finishing touches to a little flannel for the baby, when without

any warning, the quiet noonday stillness was broken with rapid gun firing, a

silence, then more firing; and then the heavy boom of artillery. Pandemonium

seemed to reign outside the home; and within, things began to stir. The baby

awoke crying, the school teacher, the children, and neighbors with their

children, rushed in. And then a town officer came, ordering all inmates of this

part of town to seek refuge in an old gin house situated under the brow of a

hill. It was regarded as a safer place for the women and children, for a fight

was beginning to take place on the western edge of the town, and bullets were

flying in every direction. The battle of Oakland had commenced. Gen. Washburn

had left Helena, Ark., and a section of the Confederate army, under the command

of Gen. Sterling Price, had been sent forward to intercept the Federals here at

Oakland. These Confederate troops had thrown up temporary breastworks just

northwest of the town. The Confederates were driven from behind these works,

and for a short time there was brisk fighting, with the Federals eventually

driving the Confederates from the field of conflict.

A number of horses were killed, and some

prisoners were taken, and men wounded, but if any were killed it was not

reported. My mother hastily gathered together her children, some Negroes, and

different articles of value that could be carried, (the dinner was forgotten)

and all hurried to the old ginhouse, under the brow of the hill; and there they

remained for nearly two hours.

The

gun-firing having ceased, they anxiously returned home, when within sight of

the house they were dismayed to find the road, yards and house filled with

soldiers in blue coats, but they pushed their way through. And on entering her

room, my mother found a badly wounded Confederate prisoner on her bed. A doctor

and guard were with him, and my mother, aunt and the Connecticut school teacher

quickly got busy tearing old sheets, and rolling bandages, helping to make the

prisoner more comfortable; but in a very short time the soldiers hurriedly

left. News had come of the rapid approach of more Confederate troops, and the

Yankees quickly retreated to Helena, Ark. They carried with them several

prisoners, but left with us the wounded Confederate Captain, and it was not

until the following April that he was well enough to leave for his home in

Texas. My father came home about the middle of the afternoon. He had not lost a

bale of cotton, but they found and appropriated several horses, and a few of

the Negroes followed the Yankee army. After my father came, he and my mother

went over the house and yards to see what damage had been done. They found

every crumb of the dinner had been eaten, dishes broken, and the table and floor

stuck up with peach, quince, and plum preserves; for the soldiers had invaded

the pantry and helped themselves to every jar of preserves. They had broken

into the smokehouse but found nothing of value, for Brister and John, two

faithful servants, had on the previous night transferred the bacon, the

shoulders and hams to the dark loft above the back gallery. They had placed

back the transom, covering edges with the wall paper, thereby leaving no trace

of their entrance to a loft. The soldiers had gone to every room searching the

beds and closets for the Confederate Captain's pistols, but they did not look

in a clothes basket on the back gallery, where they had been placed by the

Connecticut school teacher, who was loyal to this southern household, in which

he had made his home for several years. When the Captain left for his Texas

home, he carried his pistols with him. The yards did not escape so lightly, and

Jimmie the gardener was completely overcome, for the fences were broken down

and his lovely flower beds had been trampled. The scrubs and trees had been

bitten off by the soldiers horses, but in this raid we escaped lightly, for

with a few weeks work, the yard was restored to its former beauty. And even now

several of the rose bushes and trees are living; among them a beautiful pink

crape myrtle.

About two weeks after this, the family had

assembled for the noon meal, when a soldier in the uniform of a Confederate

major rode up the gate and asked if he could get dinner. He was courteously

invited into the room, and ate most heartily. After eating, he thanked my

mother "for the best dinner I have eaten in weeks" and hurriedly

left. My mother at once said that, notwithstanding the Confederate uniform, she

felt sure he was a Yankee - for she had detected the accent. And then too, he

did not touch a dish of lovely sweet potatoes. Her suspicions proved correct,

for a mile or two further he stopped at a blacksmith shop. The blacksmith also

suspected him, and with the aid of a Confederate soldier who just happened in,

arrested him and took away his arms; but he escaped, riding off in a shower of

bullets. In a subsequent raid, they visited the plantation and carried off ten

or more mules, and more Negroes followed them. But a majority of the Negroes

came back home, and lived here until they died of old age."

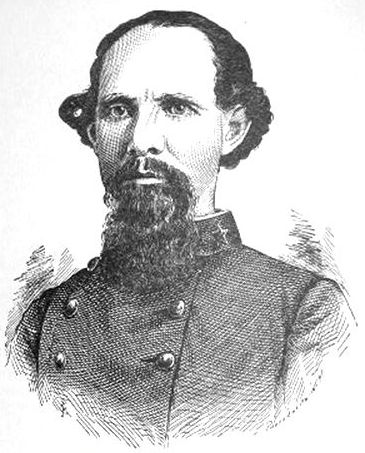

Confederate

Report:

Report of

Lieutenant Colonel John S. Griffith, Sixth Texas Cavalry, commanding Cavalry

Brigade, of skirmish at Oakland, Miss., December 3.

Texas Lt. Col.

John S. Griffith

Griffith

stopped the Union flank in Oakland and also presented Pemberton with the idea

of raiding Holly Springs, which Van Dorn later did successfully. From that point, Confederate cavalry was

employed more and more to make quick strikes against Federal installations.

HEADQUARTERS FIRST TEXAS CAVALRY BRIGADE, Yalabusha

County, Miss., December 5, 1862.

GENERAL: In obedience to your order I left

Tobytubbyville on the 29th ultimo with the First Texas Legion, numbering 458

men, under command of Lieutenant

Colonel [E. R.] Hawkins; the

Third Texas Regiment (437 men),

commanded by Lieutenant Colonel [J. S.] Boggess; the Sixth Texas Regiment

(369 men), commanded by Captain Jack

Wharton, and Captain Francis McNally's

battery of four guns, under command of Lieutenant David W. Hudgens.

On the 30th I arrived, after a forced march, at

Oakland, and hearing that a body of 2,000 of the enemy's cavalry had crossed

the Memphis and Grenada Railroad 5 or 6 miles south of this point en route for

Coffeeville, and to destroy the Central Railroad between this place and

Grenada, I gave pursuit. The enemy hearing of my approach fled back to

Charleston and Mitchell's Cross-Roads, near to Bird's Ferry, on the

Yocknapatalfa.

On the 1st instant I went down on the west side of the

Central Railroad to Grenada, restored confidence there, causing several trains

to be sent up to the army then retreating. Called on General Winter, who was

then in command at this point, and by whom I was informed that the enemy were

in Preston in strong force. I determined to go to Preston at once, attack and

harass them, and, if possible, keep them off our train then coming down the

Central road to Grenada, knowing that if they proved too heavy for me I could

show them that Texans could retreat when necessary as well as fight. The rain

pouring down in torrents making the roads heavy, I left my battery with a small

detachment of men whose horses had already given out by the continued forced

marches I had made from pillar to post in order to both find the enemy and create

an impression upon them that there was a large force in this section.

On the 2nd instant I dashed into Preston and found the

enemy had fallen back to Mitchell's Cross-Roads for re-enforcements upon

hearing I had arrived at Grenada.

On the morning of the 3rd I moved up toward Oakland.

Arriving there I learned that a body of the enemy under General [C. C.]

Washburn, of 7,000 or 8,000 strong, consisting of infantry, artillery, and

cavalry, were moving upon Oakland from Mitchell's Cross Roads. I determined to

fight him at the junction of the road upon which he was traveling with the

Charleston road and half a mile beyond Oakland. I ordered Colonel Boggess to

make a demonstration on the enemy's left flank and rear, Captain Wharton on the

left on the Charleston road, and Colonel Hawkins and Major [John H.] Broocks, who was in command of the

advance guard, composed of three companies, to the center. Major Broocks, being

in advance, engaged the enemy. Colonel Hawkins, dismounting his Legion under

cover of a small hill, moved up to his assistance. General Washburn moved up

through a long lane, and when he arrived within 200 yards of us opened his

batteries upon us, pouring in grape and canister at a fearful rate and with a

rapidity that excelled anything I ever saw before. I ordered the charge, and

with a wild, defiant shout the two commands double-quicked it, took the

battery, drove back its support, and still pressed on. While this battery was

being taken the enemy planted another on their right and commenced cross-firing

upon me. I immediately ordered Captain Wharton to dismount his regiment and

take that battery. He dismounted his men with the usual eagerness he evinces to

discharge his duties in times of danger. At this particular juncture I was

informed that the enemy was flanking me on my left. Having fought them a

spirited battle of some fifty minutes, I ordered my command "To

horse." The safety of the command demanded an immediate withdrawal, which

was done in good order to Oakland, where I again formed.

My loss was only 8 wounded (all brought off the field),

2 of whom (severely) were taken to a private house and left in charge of one of

my surgeons and a nurse. The enemy lost several killed and, I have learned

since, 18 wounded. Some of the horses belonging to the battery having been

killed, I could bring away but one of the pieces of artillery and 4 prisoners.

Six-shooters, coats, blankets, hats, &c., dropped in such rich profusion by

General Washburn's body guard, were picked up and borne away in triumph by my

boys.

I remained at this place some half an hour. Finding the

enemy had concentrated his strength I fell back 2 miles and selected a place to

give him battle. He however showed no disposition to follow me, and toward

night I fell back 8 miles to a place of safety that my men might rest, as they

had had but little sleep or rest for five days and nights in succession.

On the following morning I moved up to fight him again

and found he had gone back to the cross-roads. I occupied the place until night

and fell back 4 miles and went into camp.

To Colonel Boggess and Captain Wharton I am obliged for

the promptness with which they obeyed my orders during the engagement of the

3d. It was their misfortune and not their fault that they were not under fire.

To Colonel Hawkins, for his skill as well as gallantry,

and to Major Broocks, who displayed in an eminent degree those two traits of

character so absolutely necessary in a military commander-prudence combined

with desperate courage-I am especially indebted for the success attending my

efforts.

I would not forget my other officers and men, but to

mention the names of some where all did so well would be an injustice, when

each, in the face of terrible volleys of musketry, canister, and grape-shot from

the artillery, charged to the cannon's mouth and sent back in dismay the

invaders of our soil, beaten and fleeing as chaff before the wind; nor would I

forget Providence, to whom all the praise is due.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

JOHN S. GRIFFITH,

Lieutenant

Colonel [Sixth Texas Cav.],

Commanding First Texas Cav. Brigadier ,

Maury's Division, Army of West Tennessee.

Major

General EARL VAN DORN.

P. S.-General Van Dorn will

pardon me for sending a report with so many interlineation, &c. It is all

the paper I have, and cannot therefore copy it.

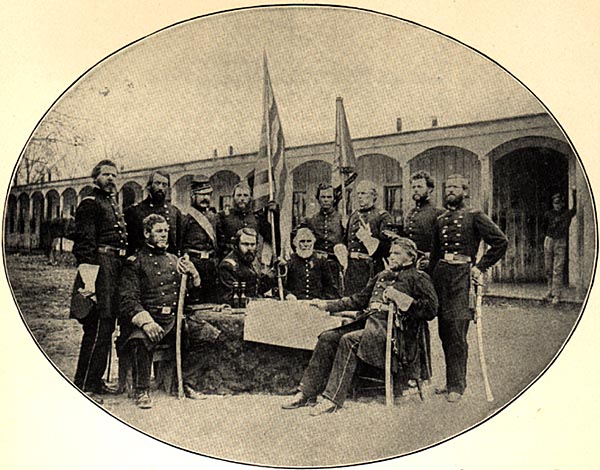

Union Report:

|

|

|

General Washburn & Staff

Washburn was also a US

congressman and later the Republican governor of Wisconsin from 1872-74.

He also formed Washburn,

Crosby, & Company. Today it is

known as General Mills.

HEADQUARTERS CAVALRY DIVISION, Mouth of Coldwater

River, Miss., December 4, 1862.

CAPTAIN: I have the honor to report in regard to the

operations of the forces placed under my command in connection with the

expedition into Mississippi that the force was embarked and sailed from Helena

at about 2 p. m. on Thursday, November 27. The embarkation was delayed several

hours in consequence of insufficient transportation and negligence on the part

of the quartermaster in not having the boats, which had been long in port,

properly called and in readiness. In consequence I was not able to make my

landing at Delta and disembark the cavalry forces which composed my command

until after dark. The force I had with me was 1,925 strong and consisted of

detachments from the following regiments, viz: First Indiana Cavalry, 300,

commanded by Captain Walker; Ninth Illinois Cavalry, 150, commanded by Major

Burgh; Third Iowa Cavalry, 188, commanded by Major Scott; Fourth Iowa Cavalry,

200, commanded by Captain Perkins; Fifth Illinois Cavalry, 212, commanded by

Major Seley. Total, 1,050.

The above I formed into one brigade under the command

of Colonel Hall Wilson, of the Fifth

Illinois Cavalry.

Sixth Missouri Cavalry, 150, commanded by Major

Hawkins; Fifth Kansas Cavalry, 208, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Jenkins;

Tenth Illinois Cavalry, 92, commanded by Captain Anderson; Third Illinois

Cavalry, 200, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Ruggles; Second Wisconsin Cavalry,

225, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Sterling. Total, 875.

The last named were placed under command of

Colonel Thomas Stephens, Second

Wisconsin Cavalry.

As soon as possible after landing I took up my line of

march for the interior and bivouacked for the night about 8 miles from the

Mississippi River. I took no tents or baggage of any kind, and about three

days' rations. I broke camp at daylight on Friday and marched 35 miles on that

day to the west bank of Tallahatchie River, just below its junction with the

Coldwater.

During this day's march we captured several pickets and

conriers. We found that reports of our landing had preceded us, and the

impression prevailed that we were approaching in great force. From negroes that

we met we learned that there was a force of rebel cavalry encamped at the mouth

of Coldwater, and that a large party of negroes had been collected near there

to blockade the road and throw up fortifications. Wishing to surprise them, if

possible, I delayed the column slightly, so as not to arrive at the river until

after night-fall. As we approached the ferry where they were supposed to be

encamped I ordered Captain Walker, who commanded the detachment of First

Indiana Cavalry, to dismount a party of his men and throw them forward as

quietly as possible to the bank of the river, and at the same time to detach

his horses from his small guns and have his men run them quietly forward by

hand. He soon came in sight of their camp fires on the east bank of the river,

and could distinctly see large numbers of soldiers moving around them. They

were laughing, talking, singing, and enjoying themselves quiet merrily. Captain

Walker immediately brought his guns to bear at a distance of about 300 yards

and opened out with all four at once, while the dismounted men poured a volley

into them from the river bank. The enemy fled with the utmost precipitation,

leaving many horses and arms upon the ground. The next day 5 of them, very

severely wounded, were found in houses by the road-side, and the negroes

reported that they had 3 killed in the engagement.

I encamped for the night on the banks of the

Tallahatchie River. The river at this point is deep and sluggish, and is about

120 yards across. We here found a ferry with one ferry-boat, 40 or 50 feet in

length. It was my intention to bridge the river during the night, and for that

purpose I took along with me 5,000 feet of inch pine lumber and five small

boats, sent from Memphis; but an examination of the boats proved them to be

leaky and worthless, and we had to delay operations until morning. Being

convinced that the means furnished for bridging were wholly inadequate, I

dispatched parties up the Coldwater and down the Tallahatchie to hunt for

boats. They found two large flats up the Coldwater, but they found the river

full of snags, and it was not until nearly 4 p. m. that they succeeded in

getting them down. By 4.30 p. m. I had the bridge completed, and by 6 p. m. I

had my entire force of cavalry on the eastern bank of the river. My orders were

to march my force as rapidly as possible to the rear of the rebel army and

destroy his telegraphic and railway communications. To do the latter the most

effectively I thought it best to march directly on Grenada, knowing that there

were there two important railroad bridges across the Yalabusha River-the one on

the Mississippi Central Railroad and the other on the Mississippi and Tennessee

Railroad. The distance to make to reach Grenada was 56 miles, but by pushing

hard I deemed it possible to reach there by daylight next morning. After

proceeding nearly east, along the Yocknapatalfa River (commonly called the

Yockna), about 11 miles, the roads fork, one road going to Panola, the other to

Charleston and Grenada. A few yards from the forks of the road, on the Panola

road, is a ferry across the Yockna, and the head of my column turned down the

Panola road to the ferry to water their horses. They were at once fired upon by

a heavy rebel picket. Major Hawkins, of the Sixth Missouri, immediately brought

his small howitzers to bear, and we soon silenced the enemy and drove him away.

We afterward learned that they were the pickets of a cavalry force of 3,000,

who were encamped 6 miles up the Panola road, who on hearing our guns supposed

we were bound for Panola, and they retreated to that point. After leaving this

point we were several times fired upon by the pickets of the enemy, which

compelled us to feel our way during the night.

At daylight I found myself at Preston, a little town 16

miles from Grenada. When I arrived here I found it would be impossible for me

to reach Hardy Station, the first station above Grenada, on the Mississippi and

Tennessee Railroad, in time to intercept the up train, which I ascertained

usually left at 8 a. m. I detached Captain

A. M. Sherman, Second Wisconsin Cavalry, with 200 men of the Second

Wisconsin and Fifth Illinois, to cross over to the Mississippi and Tennessee

Railroad, at Garner Station, which was only 4 miles distant, and destroy the

telegraph and such bridges as he could find, and if possible to capture the

train. He burned one bridge over 100 feet long and cut the telegraph. He was

also instructed on leaving Garner Station to cross through the woods to the

Mississippi Central, a distance of 9 miles, in an air line, and hunt for and

destroy bridges and cut the telegraph. This last, from the character of the

country to be passed over, be found would be impracticable. The train from

Grenada did not come up. With the remainder of the column I passed on down

toward Grenada. About 9 a. m., my horses being thoroughly jaded, I found it

necessary to stop and feed and rest them, which I did for about two hours. I

then passed on to Hardy Station. About half a mile below the station I found a

bridge about 100 feet in length, which I burned, and also destroyed several

hundred yards of telegraph wire, and one passenger, one box, and ten platform

cars. We here learned that our coming had preceded us by several hours, and

that the evening previous 1,100 infantry had come down the road from Panola to

Grenada.

At Hardy Station the road we traveled crossed the

railroad and passed down between the Mississippi and Tennessee and Mississippi

Central. Passing down the road toward Grenada for about 2 miles, and hearing

from the negroes that trains of cars were running all night down the Central

Railroad toward Grenada, loaded with soldiers, being in a perfect trap between

the two railroads, in a low and densely wooded bottom, with no knowledge in

regard to roads, and knowing that they had had time to send ample force from

Abbeville, I deemed it too hazardous to proceed farther in that direction. I

here detached Major Burgh, of the Ninth Illinois Cavalry, with 100 men, armed

with carbines, crow-bars, and axes, and directed them to cross the country,

through the woods and canebrakes, until they should strike the Central

Mississippi Railroad, and then destroy the telegraph and all the bridges they

could find. They successfully performed the service, destroying the telegraph,

tearing up the railroad track, and burning one small bridge, being the only one

they could find, they having an uninterrupted view of the track for a long

distance each way. White thus employed a train of cars loaded with soldiers

came slowly up the track from toward Grenada, apparently feeling their way to

find out where we were. They fell back on discovering Major Burgh and party.

Major Burgh, having done all the damage to the railroad he could, fell back to

the main column.

By this time it was nearly night; my horses and

men were too thoroughly tired out and my knowledge of the country was too

limited to justify me in periling my whole force by venturing farther, and I

accordingly fell back about 15 miles and encamped for the night. Before doing

so I hesitated as to the route I should take on my return. I was at the point

where the main road from Abbeville and Coffeeville intersected the road I

passed down upon, about 5 miles from Grenada. I felt the importance of striking

Coffeeville and destroying some bridges that I heard of there, and from there

fall back via Oakland, on the Mississippi and Tennessee road. Coffeeville was

13 miles off and Oakland 30; but on reflection I determined not to do so. Had I

taken the other road the result might have proved disastrous.

Sunday night a force of 5,000 rebel cavalry came into

Oakland in pursuit of me with two field pieces. After feeding and resting for a short time they proceeded on to

Grenada via Coffeeville. Had I taken the other road via Coffeeville, and the

only other one by which we could return, we should have encountered this force.

As we should have been compelled to go into camp from sheer exhaustion soon

after leaving Coffeeville they would no doubt have come upon us in camp, and

with more than double our numbers and a perfect knowledge of the country they

would have had us at great disadvantage.

On Monday morning I broke camp, 4 miles beyond

Charleston, and marched to Mitchell's Cross-Roads, 12 miles from the mouth of

Coldwater, where we found that General Hovey had sent forward to that point

about 1,200 infantry and four field pieces. I had scarcely arrived at

Mitchell's Cross-Roads when word came into camp that two companies of infantry,

sent out by Colonel Spicely on the Panola road as a picket, were fighting and

in danger of being cut off. Without waiting an instant I threw my force

forward, Captain Walker, of the First Indiana, with his little howitzers in

front, and Major Burgh, of the Ninth Illinois Cavalry, immediately following.

As soon as we came in sight of the enemy Captain Walker and Major Burgh brought

their guns into position, and a few well-directed shots sent the enemy flying.

The enemy was posted on the north side of the Yockna, a deep stream about 125

feet wide, crossed by a ferry. I immediately threw a portion of Captain

Walker's command across the stream, who pursued them lively for a few miles,

until farther pursuit was useless. This force was part of Starke's cavalry.

Being now entirely out of rations I sent into the mouth

of Coldwater, where the supply train was, for two days' rations to be sent out

during the night, intending to march early next morning and endeavor to reach

Coffeeville. My men had their horses saddled up and in readiness at daylight,

but no rations came. Owing to the breaking down of wagons they did not come up

so that the rations could be distributed before 2 p. m.

This day, Tuesday, December 2, it rained incessantly

all day. Not being able to march on Coffeeville, owing to the want of rations,

and knowing that the enemy were in considerable force at Panola, on the

Tallahatchie, 14 miles from my camp, where they had fortified to defend the

crossing, and also at Belmont, 7 miles farther up the river, I concluded that I

would go up there and reconnoiter and if possible drive these forces away, so as

to have no force in my rear when I should move toward Coffeeville the following

day.

I left camp about 2 p. m. and rode rapidly to Panola.

About 1 1/2 miles before reaching the town we came upon their camp (apparently

a very large one), but we found nobody to receive us, they having fled the

night before. I sent Major Burgh with the Ninth Illinois Cavalry forward, who

took possession of the town and captured a few prisoners. We also ascertained

from negroes who had been at work on the fortifications at Belmont that they

abandoned their works there and fled in great precipitation when they heard of

our approach. After occupying Panola we returned same night to our camp near

Mitchell's Cross-Roads. I did not disturb the railroad at Panola or burn any

bridge, having already rendered it useless to the rebels and knowing we should

want to use it very shortly.

The next morning early I took up my line of march for

Coffeeville via Oakland. I ordered Colonel Spicely, who was in command of the

advance infantry and artillery force, to throw forward for my support as far as

Oakland 600 infantry and two field pieces, which he did, under the command of

Lieutenant-Colonel Torrence, Thirtieth Iowa Infantry. The roads were very heavy

and the march was tedious. As we approached Oakland our information was that

there was no enemy there and had been none since Sunday night; but about 1 mile

before reaching town the advance guard from the First Indiana came in sight of

2 or 3 rebel pickets. Each party fired, and the pickets fled, hotly pursued.

The road here was narrow and the ground on both sides lined with a dense growth

of small saplings, with a fence on each side. The advance immediately formed in

line so far as the nature of the ground would admit. They found the rebels dismounted

and drawn up in line in large force in a most advantageous position. The

advance stood their ground manfully and delivered their fire with great

coolness and precision. After delivering their fire the enemy charged upon them

in great force, and the ground being such as to render it impossible for them

to reform, they were compelled to fall back about 200 yards to an opening,

where I was able to deploy to the right and left of the road. Supposing that

the force was the large cavalry force that occupied Oakland on Sunday night I

felt impelled to move with much caution and beat up the woods as I proceeded.

This occupied some little time, we in the mean time having got our howitzers in

position and shelled the woods in all directions where an enemy seemed

probable. Advancing with our lines extended we entered the town just in time to

get sight of the enemy. Colonel Stephens, commanding the Second Brigade, having

deployed on the left, was first to enter the town, and as soon as he came in

sight of the enemy charged upon them and drove them with great rapidity through

the town and down the road to Coffeeville. We captured a number of prisoners,

horses, arms, and 5,000 rounds of Minie-rifle cartridges, and we found at

different houses in town about a dozen so badly wounded that they could not be

taken away, among them Captain Griffin, of the First Texas Legion, whose arm

was shattered by a pistol ball; also a chaplain, surgeon, and 2 lieutenants of

a Texas regiment. Some of their wounded were fatally so.

I have to report no loss of men during the engagement,

but about 10 men wounded, only 1 of them seriously. The First Indiana lost 8 or

10 horses, which were killed during the engagement, and my body guard had 6

horses killed, and Lieutenant Meyers, commanding the body guard, had his horse

shot under him and a bullet shot through his coat. I regret to have to report

that during the confusion that ensued when the enemy charged on the head of our

column, and before the First Indiana could get their guns in position, one of

them, which had been too far advanced to the front, was captured and borne off

by the enemy. This is the only event of the expedition that I have cause to

regret; and yet knowing as I do from personal observation the determined

character of the first onset of the enemy I do not regard the event as

surprising, or one for which the company to which the gun belonged is

censurable. The conduct of Captain Walker throughout is worthy of all praise.

When at Oakland I was 15 miles from Coffeeville. From

prisoners captured and from citizens I learned that the rebel army had fled

from Abbeville and were falling back rapidly via Water Valley and Coffeeville.

I also learned that the cavalry force which we encountered at Oakland were

Texas troops and about 1,500 strong, and were part of a force which left

Coffeeville that morning in pursuit of me; that it was divided into three

different parties, each of about that number, and left on as many different

routes. Concluding that they would all fall back on Coffeeville, and being

satisfied that more or less force from Price's army was at Coffeeville, I

deemed it highly imprudent to proceed farther, as my whole force of infantry

and cavalry did not exceed 2,500 men. I bivouacked for the night on the public

square at Oakland. Though near the enemy in large force, with the precautions I

had taken I felt perfectly secure. I knew that the enemy was retreating on the

road not 10 miles in an air line from me, but I felt confident that he was in

too great a hurry to turn aside to fight me, particularly as they had received

such exaggerated reports of the forces under General Hovey's command. I

determined to remain here and send back for a portion of the remaining infantry

to be sent up to my support, that I might proceed on to their line of retreat

and harass them as they passed; but about 12 o'clock at night I received a

dispatch from General Hovey transmitting a dispatch from General Steele stating

that the object of the expedition had been fully accomplished and ordering the

entire force to return to Helena immediately. I allowed my men to rest quietly

at Oakland until morning, when I quietly and deliberately, but reluctantly,

returned.

The day I returned from Oakland it rained hard all day,

and with the previous rains was calculated to excite just apprehensions that we

could not get back with our artillery to the Mississippi across the low

alluvial bottom which we had passed over in going out. No person that has not

passed over this road can have a just estimate of it in a wet time. For 50

miles from the Mississippi or 10 miles beyond the Tallahatchie the land is an

alluvial formation filled with ponds, sloughs, and bayous, and subject to

annual overflow, and the roads are impassable as soon as the fall rains begin.

In conclusion I beg to say that the result of the

expedition has on the whole been eminently successful. Had I possessed in

advance the knowledge I now have I could have done some things I left undone;

but my main object, which was to stampede the rebel army, could not have been

more effectually accomplished. At no time, except at Oakland, had I over 1,925

men, and then I had 600 infantry and two field pieces, which came up just at

night. The impression prevailed wherever we went that we were the advance of a force

of 30,000 that was to cut off Price. The infantry sent forward to my support at

Mitchell's Cross Roads consisted of the Eleventh Indiana, Colonel Macauley,

400; Twenty-fourth Indiana, Lieutenant-Colonel Barter, 370; Twenty-eighth and

Thirtieth Iowa, Lieutenant-Colonel Torrence, 600, and an Iowa battery, Captain

Griffiths, all under the command of Colonel Spicely, of Indiana, an able and

efficient officer.

Of the temper of both officers and men under my command

I cannot speak in too high terms of praise. From the time of my landing at

Delta to this time my command has marched over 200 miles. The weather for two

days out of six has been most inclement, raining incessantly. Without tents of

any kind and not a too plentiful supply of rations, I have never heard a word

of complaint or dissatisfaction. The health of the command has continued

excellent.

To my personal staff, who accompanied me on the

expedition, Captain W. H. Morgan,

assistant adjutant-general; Capts. John Whytock and G. W. Ring, I am under many

obligations for efficient services.

Respectfully, yours,

C. C. WASHBURN,

Brigadier-General.

Captain JOHN E.

PHILLIPS,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

***

|

Return to "Grant Moves South" |