Since Wilhelm von Roentgen announced on 28 December 1895 his discovery of invisible x-rays,and two months later Antoine Henri Becquerel reported on mysterious and penetrating "uranium rays", the social status of ionizing radiation has oscillated between enthusiastic acceptance and rejection. Following the publication in Nature in January 1896 of an x-ray photograph of the hand of Dr. Roentgen's wife, and the announcement by Pierre Curie, in , that the new radiation destroys sick cells in animals - the first step towards the "Curie-therapy" of cancers - radium and x-rays became widely accepted as an efficient tool for the diagnosis and cure of many ailments.One hundred years ago W. Shrader at the University of Missouri found that guinea pigs infected with diphtheria bacteria which were exposed to x-rays survived, whereas unirradiated controls died within 24 hours (36). Soon it was recognized that radiation is beneficial not only in high doses applied for the treatment of malignant neoplasms, but also in small doses used in diagnostics,balneology etc. Becquerel himself remained a bit skeptical and once, according to Eve Curie (daughter of Marie Sklodowska-Curie) stated: "I love radium, but the stuff snarls at me". This was after he suffered a skin burn on his chest in 1900, caused by a radium vial which he carried in the vest pocket. The first paper on the acute adverse effects of new radiation (which included dermatitis, erythema, deep skin lesions, and epilation) was published in the year after Roentgen's discovery, and contained a descripton of the first victim, a German engineer (38). During the first five years, before simple measures of precaution were adopted, 170 cases of radiation injury were recorded (56). The first students and users of radiation, voluntarily exposed themselves to high radiation doses, which resulted in the death of about 100 persons by 1922, and a total of 406 persons, whose names (including Marie Sklodowska-Curie) are recorded in "Book of Honor of Roentgenologist and Radiologist of All Nations", published in Berlin in 1992. This early experience sounded an alarm and the need for protection against high doses of radiation was finally realized.

In the 1920s the concept of "tolerance dose" was introduced, defined as a fraction of a dose causing reddening of the skin. This fraction corresponded originally to an annual dose of 700 mSv (in modern units), in 1936 it was reduced to 350 mSv, and in 1941 it was reduced further to 70 mSv. The concept of tolerance dose was based on observations of exposed persons, mainly roentgenologists, showing that a person can be continuously irradiated up to a certain level of dose without apparent adverse effects. For the next three decades this concept, which was effectively statement of threshold, served as the basis for radiation protection standards (31). Until the end of the Second World War, ionizing radiation and radionuclides were generally regarded as a blessing for humankind. It was after the war and development of nuclear weapons, that this opinion changed into radiophobia, an irrational fear that any level of radiation is dangerous. The concern about great doses of ionizing radiation, such as could be encountered at a nuclear battle-ground, in a beam of cyclotron radiation, or received by the 28 fatal victims of the burning Chernobyl reactor, is obviously justified. However, the fear of small doses, such as absorbed from Chernobyl fallout by inhabitants of Central or Western Europe, is about as justified as a fear that a temperature of 20 C may be hazardous, because at 200 C one can easily get third degree burns. Radiophobia, perhaps the most widely spread and influential superstition of the second half of the 20th century,has as its main driving force the hypothesis of the no-threshold, linear relationship between radiation and its effects on the living organism.

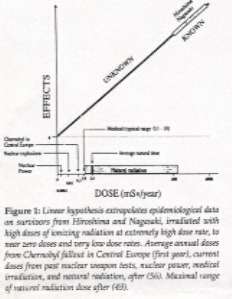

The linear hypothesis assumes that harmful post-irradiation effects, e.g. neoplasms or genetic diseases, appear after both high and even the lowest, near zero, doses of radiation, and only the frequency of the effects is proportional to the dose (Figure 1)

The linear hypothesis was accepted in 1959 by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) as a philosophical basis for radiological protection (25). This decision was based on the first report of the, just established, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (56). Since its very beginning in 1955, UNSCEAR has attained a rather high political position, reporting directly to the UN General Assembly, and over the years has become the most distinguished international scientific body on matters of ionizing radiation. A large part of its first report was dedicated to a discussion of linearity and of the threshold dose for adverse radiation effects.The UNSCEAR stand on this subject, about fourty years ago,was formed in an in-depth debate, not however without the influence of the political atmosphere and issues of the time.The soviet delegation,for example,submitted a proposal (supported by Czechoslovakia and Egypt,but rejected by the other ten delegations ,with two abstaining) in which a no-threshold assumption was used as a basis for recommendaing an immediate cessation of test explosions of nuclear weapons.

In 1958 UNSCEAR stated that contamination of the environment by nuclear explosions increase radiation levels all over the world, posing new and unknown hazards for the present and future generations. These hazards cannot be controlled and "even the smallest amounts of radiation are liable to cause deleterious genetic, and perhaps also somatic, effects". This sentence had a spectacular impact in the next decades, being repeated in a plethora of publications out of the context of the UNSCEAR report, and taken as an article of faith by the public. But in final conclusions the UNSCEAR made two important points:

1) "Linearity has been assumed primarily for purposes of simplicity"; and

2) "There may or may not be a threshold dose. Two possibilities of threshold and no-threshold have been retained because of the very great differences they engender".

Throughout the whole 1958 report (56) until its final conclusions, the original UNSCEAR view on linearity and threshold remained ambivalent. At example, UNSCEAR accepted as a threshold for leukaemia a dose of 4000 mSv (page 42). However, at the same time the Committee accepted the risk factor for leukaemia of 0.52% per 1000 mSv, assuming no threshold and linearity (page 115).Committee quite openly presented this difficulty, showing in one table (page 42) its consequences:continuation of nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere was estimated to cause up to 60,000 leukemia cases worldwide if no threshold is assumed, and zero leukemia cases if a threshold of 4000 mSv exists.

In the ICRP document of 1959 no such controversy appears. The problem was simplified, and it was arbitrarily assumed that there is no threshold for harmful effects of ionizing radiation. The epistemological problems related to the impossibility of finding these effects at very low doses were ignored. These problems were later taken into account by Weinberg (66) and Walinder (62,63), who discussed the fundamental limits to our knowledge in physics and biology. In an analysis of questions which can be asked by science and yet which cannot be answered by science Weinberg (66) used as an example the well known fact that to determine experimentally at the confidence level that 1.5 mSv will increase the mutation rate by 0.5%, as predicted by the linearity assumption, one would need 8,000,000,000 mice; at 60% confidence level the number is 195,000,000. Thus, the question about the effects predicted for 1 mSv is unanswerable by science; it transcends science. Weinberg proposed the term trans-scientific for such questions. Laymen,politicians, civic leaders etc., often look to scientists to provide scientific answers when scientists can offer only trans-scientific answers. In the past several decades in the field of ionizing radiation the trans-science was often cloaked in the mantle of respected science.

Over the years the working assumption of ICRP of 1959 came to be regarded as a scientifically documented fact by mass- media, public opinion, regulatory bodies, and even many scientists. The no-threshold principle, however, belongs to the realm of administration and it is not a scientific principle. Also in later years UNSCEAR stated that the no-threshold, linear dose/effect relationship is only "a cautious assumption, the validity of which has not yet been established. ... It cannot be assumed that the values of (risk factor) which can be derived from observations at high doses and dose rates also apply to small dose increments at low dose rates" (57). Professor W.V. Mayneord,one of the most notable persons in radiation protection and a former head of the United Kingdom delegation to UNSCEAR, defined this in plain words: "I have always felt that the argument that because at higher values of dose an observed effect is proportional to dose, at very low doses there is necessarily some 'effect' of dose, however small, is nonsense" (40).

For estimating risk factors for radiation carcinogenesis, based on the linearity principle, the results of epidemiological studies of about 90,000 survivors of nuclear attacks in Japan have been commonly used. These studies indicated that cancers are induced by single radiation doses,delivered in 10 seconds, and thousands of times higher than the world-wide average annual dose from natural background radiation (2.4 mSv). Whether any cancers are induced by background radiation or ordinary exposure of the general population to man-made radiation, however, was not indicated by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki studies.

The ICRP assumption on linearity was not very realistic. It was generally accepted, however,because it simplified regulatory work. The original purpose was to regulate the exposure to radiation of a relatively small group of occupationally exposed persons, and it did not involve exceedingly high costs to society. In the 1970s, however, ICRP extended the no-threshold principle to exposure of the general population to man-made radiation, and in the 1980s it extended the principle to limiting the exposure to natural sources of radiation. The dose limit for the public was in 1984 set at 50 mSv over a lifetime (26). This value is less than one-third of the global average lifetime dose from background radiation (168 mSv) and many tens or hundreds of times lower than the lifetime dose in many regions of the world.

Limiting exposure below the levels of natural radiation, at which millions of people have lived since time immemorial, is a logical consequence of the assumption from 1959: if each dose is detrimental, then one should also attempt to decrease the risk of background radiation from Mother Nature, or the risk of man-made radiation even at such trivial doses as 1 mSv per year. Yet such reasoning was less than palatable to many scientists associated with radiation protection. This was not only because of epistemological problem of trespassing beyond the limits of knowledge and because of the growing evidence of beneficial effects of low doses of radiation, but also because of the absurd practical consequences and moral aspects.

The limit of 1 mSv per year, recommended by the ICRP, was supposed to protect the general population against the appearance of so called stochastic effects (read: neoplastic and genetic diseases), caused by radiation damage to DNA. The number of natural, spontaneous DNA lesions (due to thermodynamic processes and action of free radicals (such as OH, peroxides, and reactive oxygen species) is about 70 millions per cell per year (7). This indicates how powerful are mechanisms of DNA repair, and other mechanisms of homeostasis (enzymatic reactons, apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, intercellular interactions, etc.), which in the stream of physico chemical changes keep the integrity of organisms during individual life and over thousands of generations.

When the large dose of radiation destroys the repair mechanisms of DNA (e.g. exhausts the store of repair enzymes), in the vast stream of spontaneous DNA damages a part of damages may remain unrepaired, and a cell enters the multistep process, which transforms it into a malignant phenotype. Such doses are called by Professor Gunnar Walinder, the eminent Swedish radiobiologist, "dominant doses" (63). After a total malignant transformation the cell has to divide some billions of times before a cancer forms. This means that formation of the cancer can be considered a billion-iterative system function. On the ground of principle, the outcome of such a function cannot be predicted (63). As a malignant transformation factor radiation is rather inefficient in comparison with spontaneous factors. Over 70-year lifetime annual dose of 1 mSv causes in each cell of human body about 700 damages, whereas due to natural causes there will be about 4.9 billion damages per cell (7). Probability that some of these radiation induced 700 DNA damages will cause a cancer and not some of 4.9 billion spontaneous damages is practically zero. This comparison suggests that it is absurd to propose to defend anybody against the DNA insult of about 1 mSv.

Clarke argued that vast abundance of spontaneous DNA damage is no basis for a threshold below which the risk of tumour induction would be zero, because there is "the very low abundance of spontaneous double strand damage and the critical importance of these lesions and their misrepair" (10). However, the rate of spontaneous single-stranded DNA damage in mammalian cells (8 x/cell/h) is only 25% higher than the rate of spontaneous double-stranded DNA damage (6 x/cell/h) (7). Radiation is not producing higher but rather lower proportion of double-strand DNA damage: 10/cGy single-stranded, and 0.4/cGy double-stranded (7). Radiation can induce a variety of types of mutations, from small point changes to very large alterations encompassing many genes. From recent studies of mammalian cells it is clear that radiation is most effective at inducing large genetic changes (large deletions and rearrangements). The proportion of different types of radiation induced mutations differs from that induced spontaneously: large genetic changes consist about 75% of radiation mutations, whereas only 25% of spontaneous mutations (54). These differences do not influence in a meaningful way the new fundamental implications of spontaneous DNA damages for radiation protection.

The probability of tumor formation for which several changes must occur in an irradiated cell, was calculated by Walinder (63), taking into account the results of modern oncological studies. If one assumes that the three changes (continuous growth stimulation, immortalization and changes on the cell surface) must first have taken place in order to induce a complete tumor transformation, the probability of cancer occurring at a dose of 1 mSv is 5 x 10E-11 (63). This means that one cancer death may be expected per 50 billion people after irradiation of each of them with one mSv, a far cry from the ICRP estimate of five cancer deaths per 100,000 per mSv, based on the assumption that a single event in the genome could transfer a cell into a malignant phenotype.

The absurdity of the linearity principle was brought to light by the Chernobyl accident in 1986.On the basis on this principle, and following the ICRP recommendations, about 400,000 persons were resettled in Belarus, Ukraine and Russia. They are the actual "linearity victims". Resettling caused unspeakable sufferings to people, the mass occurrence of psychosomatic diseases and a decrease of lifespan, due to stress and lowering living standards. The material losses were estimated at tens of billions of dollars. In impoverished Belarus alone the costs of resettlement,rents and compensations paid to these "linearity victims" will reach 91.4 billions US $ by 2015(48). The intervention levels for evacuation was first set as a 70-years lifetime radiation dose of 350 mSv, or about twice the world-wide average natural background dose. The Supreme Soviet in 1990 lowered this level first to 150 mSv and then to 70 mSv (28). The first two limits were in agreement with ICRP (27) recommendations for relocation in the intermediate phase of accident when the expected individual first year dose may surpass 50 mSv, what in case of Chernobyl corresponds to a lifetime dose of about 150 mSv (58). However, neither after irradiation with such small doses received in a 70-year lifetime, nor after natural doses tens and hundreds of times higher (50), has an increase in cancer death rate been ever observed.

Given the actual figures of natural radiation, one might ask why governments of various countries do not relocate populations living in areas where lifetime exposure to natural radiation exceeds 50 mSv or 350 mSv? For example, why isn't everyone evacuated from Norway, where the average lifetime dose is 365 mSv (22) and in some districts 1500 mSv (4)? Should not regions of India with average lifetime dose of 2000 mSv (51) or Iran with more than 3000 mSv (maximum 17,000 mSv) (50) be depopulated?

Using the linearity principle to calculate precise numbers of imaginary cancer death due to Chernobyl fallout at a global or regional scale (see e.g. 19) is a behavior which Dr. Lauriston Taylor, the former president of the US National Council on Radiological Protection and Measurements, defined as "deeply immoral uses of our scientific heritage" (53). More recently Professor Gunnar Walinder stated that "The hypothetical nature of this calculational method makes it completely unscientific and I consider it to be more or less criminal to specify figures of this kind, bearing in mind the damage and the anxiety they can provoke and how confusing they are..." (63).

The beneficial and protective effects of low doses of ionizing radiation have long been known. In algae such effects were found by Atkinson (2), soon after the discovery of Roentgen radiation. He noticed an increased growth rate of bluegreen algae exposed to x-rays. This was confirmed 82 years later (13). In 1943, during the early days of the Manhattan Project, it was found that the animals exposed to inhalation of uranium dust at levels that were expected to be fatal actually lived longer, appeared healthier, and had more offspring than the non-contaminated control animals. For years these results were treated as an anomaly but later studies produced similar results (9). The first UNSCEAR Report presented the results of the experiments showing longer survival times of mice and guinea pigs exposed to small doses of gamma radiation and fast neutrons. These results were interpreted by UNSCEAR as indicating the existence of a threshold, but the hormetic effect was not noticed (56).

Since the 1960s, such effects which are in direct contradiction to the linear hypothesis, have been ignored in radiation protection practice, while research on the stimulating and adaptive effects of radiation, radiation hormesis (from the Greek word hormaein, to excite) has continued over several decades, and the number of published papers on this subject surpasses 1000.

Radiation hormesis goes beyond the notion that radiation has no deleterious effects at small doses: at small doses new stimulatory effects occur that are not observed at high doses, and these new effects may be beneficial to the organism (Figure 2).

Among the research reviewed in 1994 UNSCEAR report (60), of special interest is a group of French studies started in the 1960s. These indicate that protozoa and bacteria exposed to artificially lowered levels of natural radiation demonstrate deficiency symptoms expressed as dramatically decreased proliferation (Figure 3).

The lack of sense organs for ionizing radiation in higher organisms is probably an effect of defence mechanisms superfluously covering the whole range of natural radiation levels. The range of natural doses: from <1 to 376 mSv/year (49,59) is greater than e.g., the range of normal exposure to thermal energy, covering about 50 C. Increasing the water temperature in a bath tub from 20 to 100 C ,i.e. by a factor of five ,may cause death. But a single lethal dose of ionizing radiation, delivered in about 1 hour, which for man is 3000 to 5000 mSv, is more than 10 million times higher than the average natural radiation dose received in that time. The fractionated lethal dose is even higher. The defence mechanisms developed by evolution, provide living organisms with an enormous safety margin for natural levels of radiation, and for man-made radiation from peace-time sources under control.UNSCEAR (60) reviewed numerous studies on mammals. For example, in an experiment with mice the incidence of leukemia, cancers, and sarcomas was lower in animals irradiated with cesium-137 gamma radiation doses of 2.5 to 20 mSv than it was in non-irradiated controls. The number of all malignant neoplasms in animals exposed to a single dose of 10 mSv was more than 30% lower than in non-irradiated controls (Table 1).

Click Here to Go to Part II

Feel free to send your comments to:

Biology Division , Kyoto University of Education

P.O.Box 612-0863 , Phone (81 75) 644 8266

Fax (81 75) 645-1734

Kyoto , Japan

Note: This Site Under Construction .