By D Thomas Minton

Artwork by Jose Baetas.

With our scouts committed to the defense of the northern front, it took me twelve days to find the Tembowatu. The first sign was a cloud of red dust smeared across the horizon like a smudge of blood.

A bad omen, I thought, washing the heat from my tongue with a sip from my canteen.

I set off across the ochre and beige scree on my cycle, which was old and ill-suited for the terrain. After a day, grit and heat crippled its engine. I nearly turned back, but I knew the Oluchi army stood poised to overrun my tribal lands and beat my people back into the dust and obscurity from which we had risen--those they did not slaughter, that is. So I continued on foot, stopping only to dig for water when my canteen grew dusty. I was rewarded late on the second day when I struggled to the crest of a ridge and found the Tembowatu watering their olophants at a muddy puddle.

I leaned on my rifle, panting heavily. Seeing the dark mud, I realized how thirsty I was, but I knew better than to approach the milling herd of giant beasts and their guardians.

Presently, a Tembowatu warrior hiked up to me. He wore only a pair of shorts, stained red from the mud he had smeared across his bare chest and into the dreadlocks of his hair. The dreads he had looped atop his head like a turban and affixed in place with two sticks of polished, blond wood.

"I am Masika," I said, when he stopped before me.

He balanced a long barreled rifle in his hand.

I tipped a finger of water into my canteen's dusty metal cap and extended it to him. "I bring water from the Land of the Sun and his eminence Isoba Chimola."

He eyed my offering warily. Eventually he took it from my hand. "This land is wide," he said, after he had returned the empty cup. "Surely your wives miss you."

"I hope to return to them soon," I said, "but to do that, I must first speak with Taonga." I watched his face, but saw no sign that my directness had offended him.

"These words must be important," he said.

"I bring an offer of prosperity."

For a moment I thought he would turn me away. Like most tribes, the Tembowatu and my people, the Masata, had a history of unpleasantness between us. Our war with the Oluchi went poorly, however, necessitating the need for allies.

He grunted and pointed at my rifle. Reluctantly I handed it to him; then I followed him down the slope, trying hard not to stumble.

*****

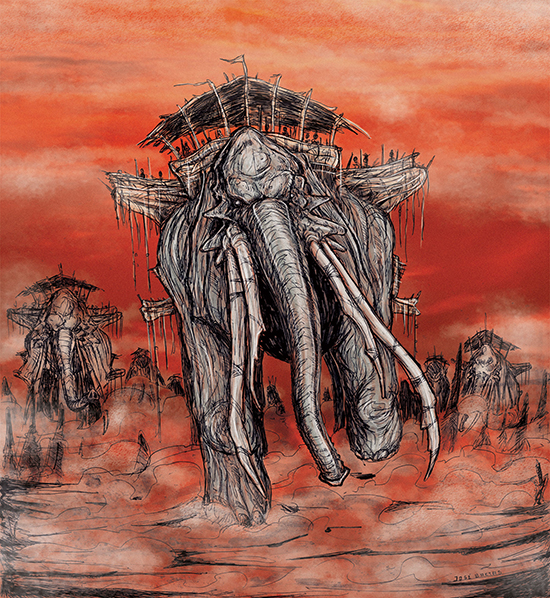

As I approached the waterhole, my neck craned back farther and farther to take in the great beasts. The olophants towered four stories over the red muck, siphoning muddy water into their mouths with thick trunks. The mud on the edge of the nearly drained hole cracked in the afternoon sun.

"Wait here," the warrior said. He trotted off, his long-barreled rifle slung over his shoulder.

Descendants of elephants, the Tembowatu olophants were all that remained of the lineage. Generations of selective breeding had resulted in their great size, and the mutualistic relationship between the olophants and their guardians had led to the development of other peculiar physical traits.

I had never believed the stories until I saw the great howdahs upon their backs. Running along their sides, from the shoulders to the flanks, were platforms of spindly camelthorn branches. Yet it was the ivory ring glinting on the olophant's side that drew my eye. It framed an opening into the side of the great beast, leading to an internal chamber in which the Tembowatu lived. The arrangement was akin to the savannah trees that provided home-chambers and nectar for ants in exchange for protection from hungry grazers.

I shielded my eyes and watched the warrior shimmy up a rope to one of the platforms and disappear through the ivory ring.

The muck squished around my ankles. The earthy stench of mud and dung crinkled my nose.

Around me, in the shadow of the olophants, Tembowatu children scooped skittering lungfish with woven grass nets. Several stopped chasing fish and cautiously eyed me from a distance. How many of them knew what my people had done to their parents and grandparents?

The ground trembled as an olophant stomped the mud, startling me.

The children laughed and went back to their fishing.

Eventually the warrior returned. "Taonga will see

you."

*****

Without the knots at knee-length intervals along the rope, I would not have managed to reach the platform twenty feet above me. The warrior motioned me toward the ivory-lined hole.

I peered into the darkness and forced myself not to turn away from the musky scent within. I stepped over the ivory frame into the gloom. The light from outside cast an oval on the floor, but did not penetrate deeply into the chamber. I stood just inside the opening, waiting for my eyes to adjust. Slowly features crawled out of the darkness.

The narrow chamber ran forward toward the olophant's head. It was inside the beast's ribs; thick bones rippled along the outer wall, curling into the floor, which was covered with soft hide mats.

A light flared at the far end of the chamber before dying back into a sputtering flame. A lamp swayed from a long cord, illuminating an old man sitting cross-legged on the floor. The dim light played off his wrinkles, making his face look like someone had drawn black lines on it with a charred twig. Two ivory sticks held his turban of woven hair in place.

I pressed my hands together and touched the tips to my forehead, bowing forward. "May you always have water and shade," I said.

Taonga motioned to a worn cloth pillow, and I sat.

He poured a white liquid into a small cup and handed it to me. The cup was hand-pounded metal, the hammer blows still visible along its surface. The liquid smelled strongly of sour musk. Fermented milk. I grimaced as it coated my tongue and the back of my throat. I handed back the cup.

Taonga poured a second measure and drank it.

"You are not of the Nyika?" he said.

Nyika was what the Tembowatu called this wasteland. "I have traveled far," I said.

Taonga nodded and let forth a soft hmmm, as if he expected such an answer. We sat for a moment without speaking. Through the chamber I could hear the soft sound of the great beast breathing and a rhythmic thump, deep in tone so that it shook my guts.

"Is there rain in Ogliwa?" he asked.

"No," I said. Several days ago I had passed through the small town on the eastern edge of the wastes.

"What about Nnamdi. Is there rain in Nnamdi?"

"I saw no rain in Nnamdi," I said. Taonga was narrowing in on Baraka, the center of the Land of the Sun and where my journey had started. "We had rain in Baraka many days ago. It wet the dust, but did not fill the aquifer."

"Are your wives well in Baraka?"

"My wives are well. They have shade and water."

"Good, good," said Taonga.

"Your shade is cool and wide," I said.

"We are blessed," said Taonga. "The rains stay away, but the waterholes are still wet."

For several years the rains had failed. To feed our crops, his eminence had diverted the river that watered the Nyika and those that flowed north into the lands of our enemies. In the last year, the rivers had brought less water, and I did not know how much longer the springs would fill the waterholes.

We talked in this manner for a while longer, slowly extracting information about each other without ever asking. I knew I had satisfied Taonga's curiosity when he finally asked, "Will you continue on to Chilagos today?"

"I do not travel to Chilagos," I said. "I bring words to the Tembowatu from his eminence, Chimola."

Taonga poured another measure of fermented milk and passed it to me. I accepted it with a bow of my head and drank it in a single gulp.

"Your milk is life," I said.

Taonga grinned strong and white teeth, which surprised me.

"His eminence praises the strength of the Tembowatu," I said. "He has sent me to negotiate an alliance."

In the flickering light, I tried to read Taonga's face, but the lay of his eyes was foreign to me.

"Our enemies threaten to overrun us" I continued. "We hold them in the mountain passes, but they will soon use their numbers to flow into the Land of the Sun. The Tembowatu can stop this from happening. In exchange his eminence will give you water that is your own."

"We have water."

"But it is not your water." The Tembowatu were nomadic, and existed only because Chimola allowed.

Taonga grunted softly, understanding my meaning. "It is our way to follow the rain," he said. "There is no water here when the rain walks north, so we walk north. Can Chimola make it rain?"

"His eminence can promise more than water. Money. Land to farm."

"We cannot drink metal. Our herd cannot eat dust. Chimola has nothing to offer."

I shifted uncomfortably on the cloth pillow. The chamber was warm enough to coax the sweat from my body. It ran down the side of my face, filled the furrow of my spine, and dripped down my sides.

"His eminence has let you live in peace--"

Taonga harrumphed loudly.

I tried to ignore him, but my train of thought faltered. It took a moment to find it again. "It is your way that friendship moves to and from." I extended my hand from my chest toward his, and back again.

Taonga leaned forward so that the light from the hanging lamp penetrated into the hollows of his face. His dark eyes narrowed. "Chimola did not bring peace. We are the buzzing fly, and he has more important wasps to fight." Taonga tapped his temple with a slender finger. "I remember the first rains that darkened the sand. I remember the blood."

My stomach tightened. Taonga's tone put a shiver through me.

I jumped when the chamber began to shake. I dodged the lamp as it swung toward me on its cord. Outside, olophant trumpets blared.

Taonga rose to his feet, riding the shifting floor with ease. "It is time for us to move."

"I wish to talk more."

"The next water is two days from here. Our shade is yours until then."

Two days would bring us to the mountains that formed the border with our enemies. There the Tembowatu would lead their herd through a narrow pass to their northern forage grounds--beyond our influence, but within that of our enemies.

I could not allow that to happen.

*****

I pulled myself up the rope to the howdah and watched quietly as the Tembowatu climbed aboard their olophants. The beasts milled through the rapidly drying mud, anxious to be underway. Once everyone was aboard, the herd set off, Taonga's olophant leading the way. From beneath the shade of the howdah canopy, I watched two Tembowatu boys perched between the beast's massive ears guide the animal north with gentle taps from a slender switch. The herd spread out behind us, twenty-six adult olophants and a dozen juveniles, lined trunk to tail. The dust rose in a fan, smearing the sky ochre red.

I stayed in the howdah, alone and ignored, until the sun dropped and the stars pricked through the purpling sky. There would be no rain tonight.

I climbed down to the platform where children sat around a bowl of stones playing kudoda. Inside the chamber, I shared a meal of flat bread and spicy meat stewed in olophant milk. They served more fermented milk and finished the meal with salted water beetles, a delicacy based on the eager eyes that watched as I ate one.

The food and the warmth and the gentle rocking of the chamber made me drowsy. My eyelids were heavy from my days of pursuit. Most of the Tembowatu did not speak my language, so I watched them silently from one end of the chamber. Occasionally I made simple gestures that I believed they did not understood. Mostly, they left me alone and went about their business of living.

Taonga stayed at the other end of the chamber, in council with a ring of serious-faced Tembowatu. To his left sat the warrior with the blond sticks in his woven hair, the one with whom I had shared water earlier that day. Several times I caught his eyes with mine, and under their predatory gaze I looked away.

I leaned against the chamber wall. The olophant's hide was warm, and I felt the thumping of its heart against my cheek. Gradually, my breathing slowed to match its rhythm, and soon I slipped into the land of sleep.

*****

Sharp pops rattled me from a dreamless sleep. The floor rolled beneath me, and I splayed my limbs to stop from being thrown in the darkness and injured. Olophant trumpets filled the night, a terrifying cacophony that set my heart racing. The pops echoed over top the cries, and I realized they were the crack of rifles.

I crawled toward the opening, barely able to stay on my hands and knees as the chamber tossed beneath me. Outside, the Tembowatu lined the platform's railing, their rifles flashing. Beyond them, the moonlit landscape reeled as the olophant charged in staccato bursts of movement. I gripped the ivory frame and pulled myself up so I could see the ground.

In the cold moonlight, dark forms scattered like ants among circular mud huts. A migrant Tabo hunting village, I realized. With each crack of the Tembowatu rifles, one of the shadows stiffened awkwardly before tumbling to the ground. Huts and several jeepnees were flattened under the olophants' massive feet. Goats bounded away into the darkness after their camelthorn palisades were splintered like kindling.

I wanted to draw away, but I could not let go of the frame without being tossed onto the floor, so I clung desperately to it, trying to hide my eyes, but unable to tear them away from the massacre.

I understood now why I had been sent to enlist the Tembowatu to our cause. They would make a terrifying ally, but an even more terrible enemy.

Within minutes the killing was over and the gunfire fell away as the olophants thundered back into the wastes.

I doubted anything remained alive in the Tabo village.

The genocide at the hands of the Tabo had happened long before any of these Tembowatu had been born, but as Taonga had said, the Tembowatu remembered the first rain that had darkened the sand. Among the tribes, old wrongs were never settled; the cycle of retribution just seemed to go round and around.

*****

I could not sleep, I think the result of the stuffy air in the chamber and the unsettling quiet with which the Tembowatu returned to their sleep. I had never seen such cold efficiency before, not even among his eminence's most hardened warriors.

I climbed to the howdah, hoping the fresh air would clear my head, and curled up in the back. My mind continued to hear the cracking rifles and the trumpeting roar of olophants as they smeared Tabo woman and children into the dust.

Silhouetted against the setting moon, the two young Tembowatu boys danced atop the olophant's head as they guided it into the darkness. From their excited voices, they still reveled in the slaughtered. My stomach felt hollow; they did not realize they had sealed the future of their children in violence.

At some point, in the warmth of the night and under the roll of the howdah, I dozed off. I was awakened at dawn by a Tembowatu leaning on the railing next to me. I recognized the blond sticks holding his weave of hair in place.

"You seek help with your war," he said, just loud enough for me to hear.

The directness of his statement caught me unaware and for several seconds I wasn't sure if I had heard him correctly. I thought perhaps my mind played tricks on me.

We were alone on the howdah, except for the two boys on the olophant's head, but that did not lessen my caution.

"I can help you," he said.

I pulled myself to my feet and leaned against the rail. I was fully alert now. "Who are you?"

"I am Dabuko."

I waited for him to say more, but he did not, as if his name was enough. I studied his profile: the height of his forehead, the prominence of his cheeks bones, his dark, sharp eyes. All, along with his flat nose, were reminiscent of Taonga.

"You are Taonga's son?"

Dabuko's face turned to me, the eyebrows up as if surprised by my deduction. "I am."

The coming conversation fell into place in my mind; it told the story of nearly every tribe. Dabuko was next in the patrilineal line, provided he had support among the other family clans. He wanted to bring a new way to the Tembowatu, and he was tired of waiting for his father to step aside or die. If I could help, he would be in my debt.

Of course, Dabuko said none of this, but as he watched me, I knew the same conversation had already played out in his head.

"I propose nothing," Dabuko said, anticipating my question. "I simply observe that we will reach the mountains before tomorrow's dawn. If something were to happen to my father before then, I would hear Chimola's offer with gentle ears. I understand that friendship must pass to and from." He swept his hand from his chest toward mine, and back again.

Dabuko left me to watch the mountains bounce along the horizon. They seemed far away, but I knew Dabuko was right; we would reach them sometime during the night. Much too quickly, I feared, leaving me little time to decide what I needed to do.

*****

My attempts to meet with Taonga were rebuffed throughout the day. He was resting, or in council, or eating, and constantly I was turned away. During meals, I watched him from the rear of the chamber as he talked with his wives or Dabuko. Never did he make eye contact with me. By late afternoon, I was convinced he was ignoring me.

I resigned myself to staring at the desolate landscape as it rolled under the pounding feet of the herd. With each passing kilometer, the mountains crept closer. Even if I had wanted to help Dabuko, how could I do anything if I couldn't even get close enough to Taonga to talk?

The sun dropped, but the air did not cool. Unblemished by clouds, the horizon was a deep purple, fading to star-filled black overhead. The olophants continued on.

I grew weary of their motion.

Alone on the howdah, I contemplated what I would tell his eminence to explain my failure. I tried in vain to find the words I would say to my wives and sons. Lost, I did not immediately notice the dark shadow join me along the howdah railing until it spoke, startling me.

"There will be no rain tomorrow." Taonga said.

"It will rain soon," I said. "It has to."

"The world is changing. The rain has walked far to the north and does not want to come back. It has taken with it the balance among our tribes."

Over the last decade the rains had become less frequent as the clouds had moved away from the Land of Sun. The Nyika had always been dry, but never this dry. I wondered how much longer the Tembowatu would find forage for their herd in the Nyika. If things did not change, they would need new lands to browse.

"Did you see rain last year?" I asked.

"I saw no rain last year."

"Did you see rain before that?"

"Yes, but not in the Nyika. This is our third trip to the Nyika without rain."

It was my turn to hmmm and nod.

"Sometimes I think the rain will never return,

because the world is different today. I do not understand a world where it

never rains."

Taonga sounded as though he might be open to discussing an alliance; then, he might not. The nuances of the Tembowatu way were difficult for an outsider. Feeling I had to say something, I said, "I do not understand it either."

Taonga grunted softly. "I remember when it would rain three or four times in the Nyika. The water would turn the ground red like blood. Water is the blood of the land. Water is the blood of our herd and the blood of the Tembowatu. We cannot survive without blood."

"His eminence can undam the rivers and return water to the Nyika," I said.

"Without the rain, there is not enough water for us all. Our herd would starve. Only the rain can bring enough grass to the Nyika. Can Chimola call the rain?"

"No."

"Then nothing else matters." In the darkness, Taonga's shadow slumped against the rail. The howdah rocked gently. The two boys guiding the olophant were barely visible against the darkening sky. Surely they would barely see us, were they even to look in our direction. If timed with the sway of the howdah, I could flip the old man over the railing.

Blood pounded in my ears. Through the night and the dust I could just see a lamp on one of the olophants behind us. The olophants were impressive war machines, capable of bringing victory to his eminence and the Land of the Sun. All that stood in the way was this frail old man, longing for a world gone into the dust.

"So you will go north?" I asked.

"We will follow the rain, as is our way."

As the howdah rocked in our direction, I moved quickly across the blackness between us and grabbed Taonga's arm. I yanked him toward the railing, intending to use the momentum of the rolling beast to hoist him over it, but Taonga spun from my grip. His hands struck me across the head with surprising strength. Off balance, I crashed against the railing. My feet came off the floor. I clawed at the air as I turned upside down, and got a hand on the railing as my feet came over. My shoulder wrenched painfully as my full weight stopped suddenly.

My body bounced against the side of the olophant. I tried to get traction, but my sandals slid off the olophant's dusty hide. I swung my left arm up to grab the railing, but Taonga slapped it aside.

My fingers ached as my grip started to fail.

"In these dry times, I worry about our future. I nearly forgot Chimola's deceit, but Dabuko said you would show your true self if tested."

If I hadn't been struggling to the hold the howdah's railing, I would have raged against Dabuko's trickery. Even as I squeezed the rail with all my strength, my fingers continued to slip.

"Friendship must flow to and from," Taonga said. "Tell Chimola we will never forget." He pried my fingers free.

Taonga's face flew up into the night as I slid down the side of the great beast and fell into the darkness.

*****

Miraculously, my fall broke no bones. For a long time, I lay in the dust listening to the fading thunder of the herd. When dawn came, I saw no dust against the horizon; the Tembowatu had passed from the Nyika into the mountains. They were gone and would not return until the grass in the north had turned brittle and the promise of rain drew them south again.

If fortune was with us, that was when we would see the Tembowatu again. Yet, with growing trepidation, I feared I would see them sooner, storming down out the mountains, their olophants trumpeting and rifles cracking, to settle the score for what we--for what I--had done.