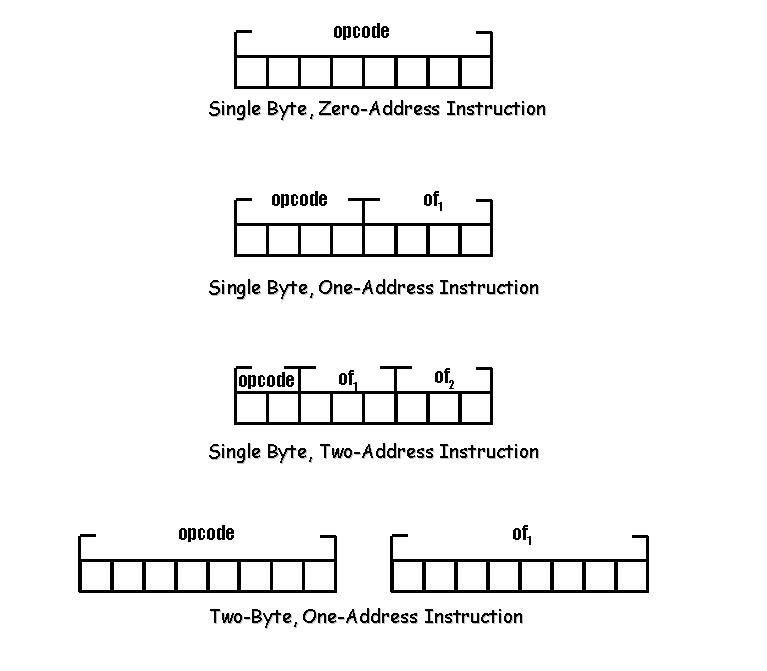

Instruction Format - defines the layout of the bits of an instruction in terms of its constituent parts. The layout of a computer instruction is a sequence of bits.

The format divides the instruction into fields, corresponding to the constituent parts of an instruction (e.g. opcode, operand). The format must implicitly or explicitly indicate the addressing mode for the operand.

NOTE: For most instruction sets, more than one instruction format is used.

SOME INSTRUCTION FORMATS OF THE INTEL 8085

The most basic design issue to be faced is the instruction format length. Instruction lengths vary from one to many bytes. The length of an instruction depends on:

This decision affects, and is affected by the following:

This decision determines the richness and flexibility of the machine, as seen by the assembly language programmer. Programmers want:

All of these things (opcodes, operands, addressing modes and addressing range) require bits and push in the direction of longer instruction lengths. But longer instructions may be wasteful. A 32-bit instruction occupies twice the space of a 16-bit instruction, but is probably less than twice as useful.

Beyond this basic trade off, there are other considerations like:

There are solutions provided for such considerations or problems:

The word length of memory is, in some sense, the "natural" unit of organization. The size of the word usually determines the size of the fixed-point numbers, wherein usually the two are equal. Word size is also typically equal to, or at least integrally related to the memory transfer size. Since a common form of data is character data, we would like a word to store in integral number of characters. Otherwise there will be wasted bits in each word when storing multiple characters, or character will have to straddle a word boundary.

Example: REGISTERS BASICALLY STORE 1 BIT

The opcode field of an 8-bit µP is fixed to 8 bits. Two address instruction employ a second byte that accumulates two 4-bit long operand fields. What is the total number of available opcodes? Up to how many registers can we encode in each operand field?

Solution

# of OpCodes = 2 n = 2 8 = 256 OpCodes

# of Registers = 2 n = 2 4 = 16 Registers

An equally difficult issue is that of how to allocate bits in the specified format. For a given instruction length, there is clearly a trade off between the number of opcodes and the power of addressing.

The following interrelated factors go into determining the use of addressing bits:

This tactic makes it easy to prove a large repertoire of opcodes, with different opcode lengths. Addressing can be more flexible, with various combinations of register and memory references plus addressing modes. With variable length instructions, opcodes can be provided efficiently and compactly.

The principal price to pay for variable length instructions is an increase in the complexity of the CPU. Falling hardware prices, the use of microprogramming, and a general increase in understanding the principles of CPU design have all contributed to making this a small price to pay.

The use of variable length instructions does not remove the desirability of making all of the instruction lengths integrally related to the word length. Since the CPU does not know how the length of the next instruction is to be fetched, a typical strategy is to fetch a number of bytes or words equal to at least the longest possible instruction. This is a good strategy to follow in any case.

Example:

The operand field expands into what is ordinarily operand field 2. Up to how many additional opcodes can we economize by doing so? Could we economize even more? What are the trade-offs?

Solution:

Additional OpCodes = 2 n = 2 5 = 32 Additional OpCodes

Trade-offs - (if all 0s) This will provide 32 opcodes. Extra opcodes would be gained at the expense of prog-flexibility because OF2 is not allowed to specify register.